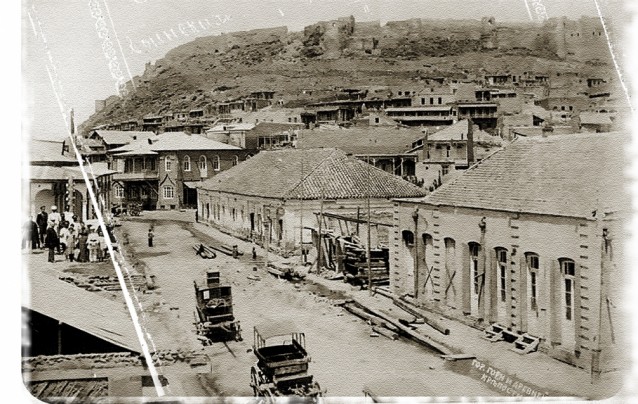

The 19th century was a time of progress and enlightenment in Azerbaijan. Many progressive ideas were circulated, moving the nation towards democratic views and national awareness. The establishment of a national dramaturgy, realist prose and theatre, the publication of newspapers and magazines in the mother tongue and the opening of new-style schools in the second half of the 19th century had an undoubted positive influence on the cultural development and progress of the nation. In this context, the opening of an Azerbaijani (Tatar) Department on 1 September 1879 at the Transcaucasian Teachers’ Seminary in Gori (in Georgia) was a highly significant event. The seminary was some distance from Azerbaijan’s borders. Travelling there was difficult via poor transport and harsh climatic conditions and this discouraged Azerbaijanis. Moreover, there were fanatical clergymen at that time who interfered with education and national revival. As a result, few Azerbaijani students were being educated. Only 3 to 5 Muslim teachers graduated each year. This, of course, could not meet the demand for teachers in the villages and cities.

The progressive intelligentsia of the time (Safarali Velibeyov, Firudin Kocharli, Rashid Efendiyev, Jalil Mammadguluzadeh and others) proposed turning the Azerbaijani Department of the Gori Seminary into an independent school and moving it to Azerbaijan in order to educate and prepare more teachers. However, the Tsarist government feared the enlightenment and education of Azerbaijanis and thus the seminary administration rejected the proposal. It would only be realised during the period of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic.

250 Muslim teachers graduated during the 40 years’ existence of the Azerbaijani Department of the Transcaucasian Teachers’ Seminary. Those graduates began working as teachers; however most of them later became theoreticians, university professors, scientists, writers, political figures, musical theorists or composers.

He walked through every village…

Aleksey Chernyayevski, a Russian from Shamakha, was appointed governing inspector at the Azerbaijani (Tatar) Department of the Transcaucasian Teachers’ Seminary. He spoke Azerbaijani perfectly and knew the lifestyle, traditions, religious views and rituals of the Muslims. He had great pedagogical experience in establishing the processes of education and the administrative organization of national schools. Chernyayevski walked through every village, every region of Azerbaijan and brought students to Gori in the face of great difficulties.

At the time there were three elementary schools (Russian, Georgian and Armenian) near the Gori Seminary that served as base schools. Seminary students gained work experience and held test lessons there. Azerbaijanis did not live in Gori, so it was not practical to open an Azerbaijani elementary school there. After the opening of the Azerbaijani department, upon Chernyayevski’s initiative, they gathered 20 children from villages all over Transcaucasia and opened a small school near the seminary. Those children were accepted into the boarding school.

When the school term started, they found that it was impossible to hold lessons, because there was no alphabet textbook in Azerbaijani. Chernyayevski immediately summoned the elder students of the seminary and held a short conference. As there was no textbook he prepared a weekly programme and reading materials for everyday oral lessons with their help. Eventually, he managed to collect many useful guides. He revised all the materials he had and prepared to compile a textbook in the future. To do this he learned the Arabic alphabet within a very short period. After teaching children for three years and acquiring great experience, he compiled an alphabet textbook from these educational materials; he called it Motherland Tongue. Chernyayevski knew that a student, Rashid Efendiyev, wrote beautifully in the Arabic alphabet, so he had him write the Motherland Tongue and had it lithographed in Rashid bey’s handwriting in 1883.

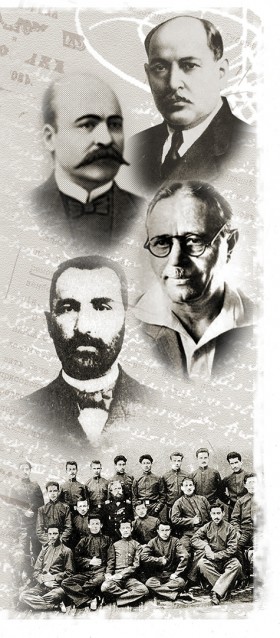

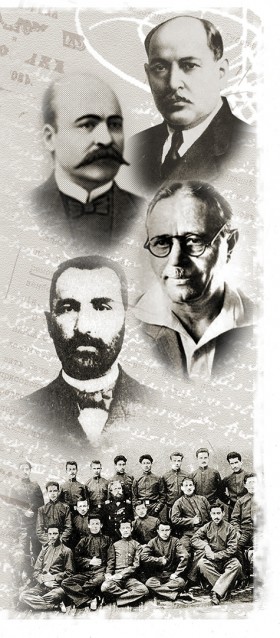

Celebrated graduates of the Gori Teachers’ Seminary,Nariman Narimanov (1870-1925),Jalil Mammadguluzadeh (1866-1932),Uzeyir bey Hajibeyov (1885-1948),Firudin bey Kocharli (1863-1920)

Celebrated graduates of the Gori Teachers’ Seminary,Nariman Narimanov (1870-1925),Jalil Mammadguluzadeh (1866-1932),Uzeyir bey Hajibeyov (1885-1948),Firudin bey Kocharli (1863-1920)

Motherland Tongue was the very first textbook for teaching the Azerbaijani language. It was written using the sovti (oral) method and had 48 pages. Each year small changes were made to the book and it was reprinted in 1910 and again later. It was from this book that Azerbaijani children learned to read and write.

Chernyayevski had a deep love for the Azerbaijani nation and he worked as an educationalist and teacher, supporting this cause for more than 25 years. However, he felt that he was being watched by Tsarist officials and resigned from the headship of the Azerbaijani Department of the seminary in 1893.

Virtue was a priority

Different oral forms of expression were used in the educational process at the Gori Teachers’ Seminary. The students’ musical skills were developed and they were taught crafts like carpentry, bookbinding, sericulture, silkworm husbandry and others. Special attention was given to the seminarians’ reading habits and they were taught the art of public speaking. Talented students wrote short stories and plays and held literary readings.

Besides the outstanding education of students, virtue was a priority. Students who missed lessons for no good reason, were late for classes, rude to their fellow students, socialized with undesirable people or broke any of the seminary’s rules were punished by the schoolmaster.

The course was three years long. There were also two-year preparation courses for students with a poor educational background. Depending on their background, the students were educated for 3, 4 or 5 years. On very rare occasions, students with an exceptionally high level of education were accepted directly into the second year. Teymur Bayramalibeyov and Safarali Velibeyov were among such students.

The further activities of graduates of the Gori Teachers’ Seminary coincided with a very difficult, complicated and contradictory period – the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Their mission was not only to educate pupils. Young teachers fought against illiteracy, superstition and ignorance. They improved the teaching of their mother tongue by increasing the number of new national schools, basing school education on new methods and seeking ways to provide education to girls. At the same time they tirelessly prepared new programmes, wrote textbooks, established charity organizations to aid education and promoted enlightenment in the press.

Lenkeran pioneer

Teymur bey Bayramalibeyov was one of these; he graduated from the seminary after just two years. He was born in the village of Yeddioymag in Lenkeran. He went first to a mullah school (a Muslim religious school), then to a two-year Russian school in Lenkeran, and on to a civil medical school in Tbilisi. Graduating from the seminary in 1881, he was then appointed as a Russian and Arithmetic teacher at the Russian two-year school in Lenkeran. There were only four students in the school at the time. Thanks to his efforts, the number of pupils rose to 16 in the first year and 36 in the third.

Bayramalibeyov attached great significance to the role of mother tongue in the educational process. He wrote in one of his articles that the tsarist education officials were trying to eliminate the mother tongue from schools, which contradicted directions from the great pedagogical theorist Kamensky, and that was why people did not want to attend school. The Russian-Tartar schools did not deliver an education appropriate to local village life.

Bayramalibeyov founded the Charity Organization so that poor children were not disadvantaged. Charity Organization funds provided children with shoes, clothing and school supplies, and helped with their school fees. He staged amateur theatre plays to raise funds for the charity. He opened a reading-room in 1906 at his own expense to promote development among the youth. Despite pressure from the Tsarist government, Teymur bey founded the Ziya (light) school in Lenkeran. The education of women was one of the most significant issues for him. In 1917 he managed to open a new-style school for girls in Lenkeran.

To help organize the work of the independent Qazakh Seminary, Firudin bey invited some of its former graduates to teach, these included: I. Gayibov, M. Veliyev, M. Mammadov, E. Huseynov, I. Vakilov, M. Huseynov and Y. Gasimov. Together with Kocharli these teachers worked hard to develop the seminary’s reputation. The number of students began to grow.

Besides teaching, Firudin Kocharli wrote hundreds of articles about the problems of education in periodicals such as Shergi Rus, Igbal, Kaspi, Novoe Obozrenie, Tiflisskiy Listok, Zagafgaziya, Gafgaz, Keshkul, Debistan, Molla Nasreddin, Rahbar and others. Some of his fundamental writings such as M. F. Akhundov, A Gift to the Little Ones, and The History of Azerbaijani Literature are still used by modern researchers. Firudin bey was the first researcher into the history of Azerbaijani literature and was an initiator of education for teachers.

The Azerbaijani department of the Gori Seminary was moved to Qazakh in 1918 but in 1920 its director, Firudin bey Kocharli, was shot dead by the Bolsheviks. Ahmad Agha Mustafayev was appointed head in his place; he worked resolutely and continued the traditions established his predecessor.

The students of the seminary were mainly from Qazakh, Shamakha and Karabakh. More than 30 students from Salahli village alone attended. Most of those attending the school in Qazakh were taught by Ahmad Agha Mustafayev, who graduated from the seminary in 1885 and worked in national schools for over 50 years.

The right to a mother tongue

Among other graduates Rashid bey Efendiyev has always been regarded with special respect. He dedicated over 50 years of his life to the education of the nation, opening schools, seminaries and teachers’ courses in the city and villages of the region and teaching in universities. He was not only a teacher, but also an eminent methodologist and pedagogical theoretician. He was born in 1863 in Nukha (now Sheki) and received his first education in the Nukha Russian School before entering the Gori Seminary in 1879. He graduated in 1882 and worked in Qutqashen (now Qabala) for 8 years. Later he opened a new-style school in Khachmaz village in Nukha and worked there for 2 years.

At that time, seminary graduates did not have the right to teach in city schools and so Rashid bey won a place in the fourth year at the Tbilisi Alexandrovski Institute for Teachers, graduating from there in 1893 and earning the right to teach in city schools. He taught until 1899 and by invitation worked at the Gori Seminary as a teacher of Azerbaijani and sharia for 17 years. During that time he wrote two textbooks: Kindergarten (1899) and Basiratul-etfal (The Quickness of Children) (1910).

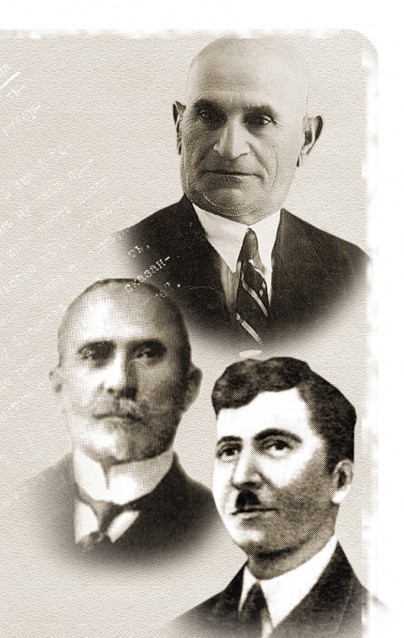

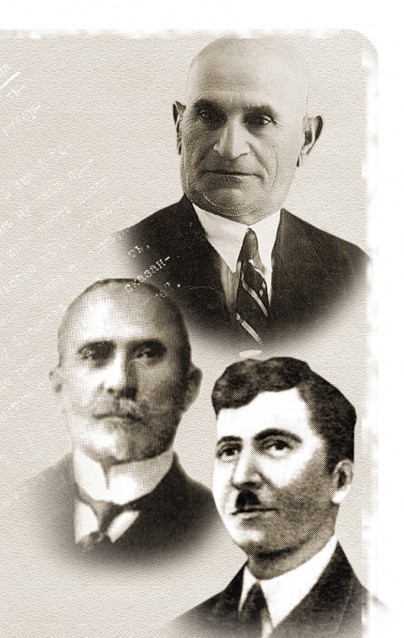

Other well-known graduates, Suleyman Sani Akhundov (1875-1939), Rashid bey Efendiyev (1863-1942), Farhad Aghazadeh (1880-1931)

Other well-known graduates, Suleyman Sani Akhundov (1875-1939), Rashid bey Efendiyev (1863-1942), Farhad Aghazadeh (1880-1931)

Rashid bey Efendiyev joined people’s struggle for their mother tongue and wrote that mother tongue was key to learning the sciences. He said that it was impossible to learn foreign languages without speaking one’s mother tongue.

He also became a famous writer. He wrote plays: House of Blood, The Virtue of a Beard, If Neighbours are True, Even a Blind Girl Will Be Married, The Price of One Hair, Rose, Toothache and many poems and stories. Rashid bey spoke fluent Arabic and contributed a great deal to ethnographic studies. He wrote a number of works on the ethnography of the Nukha and Qutqashen regions.

Much has been written about the lives, work and services to the nation of Gory Seminary graduates. Foremost among them are the world famous composer and founder of Azerbaijani national music, Uzeyir Hajibeyov, the composer Muslim Magomayev, the great democrat, writer and publicist Jalil Mammadguluzadeh, the politician Nariman Narimanov and the writer-teacher Suleyman Sani Akhundov. They were all graduates of the Gori Seminary and are still the pride of the Azerbaijani nation.

About the author: Garatel Gafarova is Head of the Exposition Department of the National Education Museum at the Ministry of Education. She is the author of research into the history of education in Azerbaijan.

The progressive intelligentsia of the time (Safarali Velibeyov, Firudin Kocharli, Rashid Efendiyev, Jalil Mammadguluzadeh and others) proposed turning the Azerbaijani Department of the Gori Seminary into an independent school and moving it to Azerbaijan in order to educate and prepare more teachers. However, the Tsarist government feared the enlightenment and education of Azerbaijanis and thus the seminary administration rejected the proposal. It would only be realised during the period of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic.

250 Muslim teachers graduated during the 40 years’ existence of the Azerbaijani Department of the Transcaucasian Teachers’ Seminary. Those graduates began working as teachers; however most of them later became theoreticians, university professors, scientists, writers, political figures, musical theorists or composers.

He walked through every village…

Aleksey Chernyayevski, a Russian from Shamakha, was appointed governing inspector at the Azerbaijani (Tatar) Department of the Transcaucasian Teachers’ Seminary. He spoke Azerbaijani perfectly and knew the lifestyle, traditions, religious views and rituals of the Muslims. He had great pedagogical experience in establishing the processes of education and the administrative organization of national schools. Chernyayevski walked through every village, every region of Azerbaijan and brought students to Gori in the face of great difficulties.

At the time there were three elementary schools (Russian, Georgian and Armenian) near the Gori Seminary that served as base schools. Seminary students gained work experience and held test lessons there. Azerbaijanis did not live in Gori, so it was not practical to open an Azerbaijani elementary school there. After the opening of the Azerbaijani department, upon Chernyayevski’s initiative, they gathered 20 children from villages all over Transcaucasia and opened a small school near the seminary. Those children were accepted into the boarding school.

When the school term started, they found that it was impossible to hold lessons, because there was no alphabet textbook in Azerbaijani. Chernyayevski immediately summoned the elder students of the seminary and held a short conference. As there was no textbook he prepared a weekly programme and reading materials for everyday oral lessons with their help. Eventually, he managed to collect many useful guides. He revised all the materials he had and prepared to compile a textbook in the future. To do this he learned the Arabic alphabet within a very short period. After teaching children for three years and acquiring great experience, he compiled an alphabet textbook from these educational materials; he called it Motherland Tongue. Chernyayevski knew that a student, Rashid Efendiyev, wrote beautifully in the Arabic alphabet, so he had him write the Motherland Tongue and had it lithographed in Rashid bey’s handwriting in 1883.

Celebrated graduates of the Gori Teachers’ Seminary,Nariman Narimanov (1870-1925),Jalil Mammadguluzadeh (1866-1932),Uzeyir bey Hajibeyov (1885-1948),Firudin bey Kocharli (1863-1920)

Celebrated graduates of the Gori Teachers’ Seminary,Nariman Narimanov (1870-1925),Jalil Mammadguluzadeh (1866-1932),Uzeyir bey Hajibeyov (1885-1948),Firudin bey Kocharli (1863-1920)

Motherland Tongue was the very first textbook for teaching the Azerbaijani language. It was written using the sovti (oral) method and had 48 pages. Each year small changes were made to the book and it was reprinted in 1910 and again later. It was from this book that Azerbaijani children learned to read and write.

Chernyayevski had a deep love for the Azerbaijani nation and he worked as an educationalist and teacher, supporting this cause for more than 25 years. However, he felt that he was being watched by Tsarist officials and resigned from the headship of the Azerbaijani Department of the seminary in 1893.

Virtue was a priority

Different oral forms of expression were used in the educational process at the Gori Teachers’ Seminary. The students’ musical skills were developed and they were taught crafts like carpentry, bookbinding, sericulture, silkworm husbandry and others. Special attention was given to the seminarians’ reading habits and they were taught the art of public speaking. Talented students wrote short stories and plays and held literary readings.

Besides the outstanding education of students, virtue was a priority. Students who missed lessons for no good reason, were late for classes, rude to their fellow students, socialized with undesirable people or broke any of the seminary’s rules were punished by the schoolmaster.

The course was three years long. There were also two-year preparation courses for students with a poor educational background. Depending on their background, the students were educated for 3, 4 or 5 years. On very rare occasions, students with an exceptionally high level of education were accepted directly into the second year. Teymur Bayramalibeyov and Safarali Velibeyov were among such students.

The further activities of graduates of the Gori Teachers’ Seminary coincided with a very difficult, complicated and contradictory period – the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Their mission was not only to educate pupils. Young teachers fought against illiteracy, superstition and ignorance. They improved the teaching of their mother tongue by increasing the number of new national schools, basing school education on new methods and seeking ways to provide education to girls. At the same time they tirelessly prepared new programmes, wrote textbooks, established charity organizations to aid education and promoted enlightenment in the press.

Lenkeran pioneer

Teymur bey Bayramalibeyov was one of these; he graduated from the seminary after just two years. He was born in the village of Yeddioymag in Lenkeran. He went first to a mullah school (a Muslim religious school), then to a two-year Russian school in Lenkeran, and on to a civil medical school in Tbilisi. Graduating from the seminary in 1881, he was then appointed as a Russian and Arithmetic teacher at the Russian two-year school in Lenkeran. There were only four students in the school at the time. Thanks to his efforts, the number of pupils rose to 16 in the first year and 36 in the third.

Bayramalibeyov attached great significance to the role of mother tongue in the educational process. He wrote in one of his articles that the tsarist education officials were trying to eliminate the mother tongue from schools, which contradicted directions from the great pedagogical theorist Kamensky, and that was why people did not want to attend school. The Russian-Tartar schools did not deliver an education appropriate to local village life.

Bayramalibeyov founded the Charity Organization so that poor children were not disadvantaged. Charity Organization funds provided children with shoes, clothing and school supplies, and helped with their school fees. He staged amateur theatre plays to raise funds for the charity. He opened a reading-room in 1906 at his own expense to promote development among the youth. Despite pressure from the Tsarist government, Teymur bey founded the Ziya (light) school in Lenkeran. The education of women was one of the most significant issues for him. In 1917 he managed to open a new-style school for girls in Lenkeran.

Moving Gori to Qazakh

Another talented and famous graduate of the Gori Seminary was Firudin bey Kocharli. He was born on 26 January 1863 in Shusha and received his first education from his father, an excellent connoisseur of Persian and Eastern poetry. After graduating from the Gori Seminary in 1885 he worked as a teacher-methodologist for 10 years at the Irevan Grammar School. In 1895 Kocharli was invited to the Gori Seminary, where he took lessons with D. D. Semyonov and Aleksey Chernyayevski and later became their friend. Firudin bey was one of the initiators of a move to transfer the Azerbaijan Department of the Gori Seminary to Azerbaijan. He worked hard to improve teachers’ education and to cover the great need there was in the country for teachers. He addressed these issues in many articles in the local press. N. Narimanov, R. Efendiyev, S. S. Akhundov, J. Mammadguluzadeh, U. Hajibeyov, F. Aghazadeh and others supported Firudin bey and put forward strong arguments in their own articles. At last all their appeals to official bodies bore results and the Azerbaijani Department was moved to the city of Qazakh.

Another talented and famous graduate of the Gori Seminary was Firudin bey Kocharli. He was born on 26 January 1863 in Shusha and received his first education from his father, an excellent connoisseur of Persian and Eastern poetry. After graduating from the Gori Seminary in 1885 he worked as a teacher-methodologist for 10 years at the Irevan Grammar School. In 1895 Kocharli was invited to the Gori Seminary, where he took lessons with D. D. Semyonov and Aleksey Chernyayevski and later became their friend. Firudin bey was one of the initiators of a move to transfer the Azerbaijan Department of the Gori Seminary to Azerbaijan. He worked hard to improve teachers’ education and to cover the great need there was in the country for teachers. He addressed these issues in many articles in the local press. N. Narimanov, R. Efendiyev, S. S. Akhundov, J. Mammadguluzadeh, U. Hajibeyov, F. Aghazadeh and others supported Firudin bey and put forward strong arguments in their own articles. At last all their appeals to official bodies bore results and the Azerbaijani Department was moved to the city of Qazakh.

To help organize the work of the independent Qazakh Seminary, Firudin bey invited some of its former graduates to teach, these included: I. Gayibov, M. Veliyev, M. Mammadov, E. Huseynov, I. Vakilov, M. Huseynov and Y. Gasimov. Together with Kocharli these teachers worked hard to develop the seminary’s reputation. The number of students began to grow.

Besides teaching, Firudin Kocharli wrote hundreds of articles about the problems of education in periodicals such as Shergi Rus, Igbal, Kaspi, Novoe Obozrenie, Tiflisskiy Listok, Zagafgaziya, Gafgaz, Keshkul, Debistan, Molla Nasreddin, Rahbar and others. Some of his fundamental writings such as M. F. Akhundov, A Gift to the Little Ones, and The History of Azerbaijani Literature are still used by modern researchers. Firudin bey was the first researcher into the history of Azerbaijani literature and was an initiator of education for teachers.

The Azerbaijani department of the Gori Seminary was moved to Qazakh in 1918 but in 1920 its director, Firudin bey Kocharli, was shot dead by the Bolsheviks. Ahmad Agha Mustafayev was appointed head in his place; he worked resolutely and continued the traditions established his predecessor.

The students of the seminary were mainly from Qazakh, Shamakha and Karabakh. More than 30 students from Salahli village alone attended. Most of those attending the school in Qazakh were taught by Ahmad Agha Mustafayev, who graduated from the seminary in 1885 and worked in national schools for over 50 years.

The right to a mother tongue

Among other graduates Rashid bey Efendiyev has always been regarded with special respect. He dedicated over 50 years of his life to the education of the nation, opening schools, seminaries and teachers’ courses in the city and villages of the region and teaching in universities. He was not only a teacher, but also an eminent methodologist and pedagogical theoretician. He was born in 1863 in Nukha (now Sheki) and received his first education in the Nukha Russian School before entering the Gori Seminary in 1879. He graduated in 1882 and worked in Qutqashen (now Qabala) for 8 years. Later he opened a new-style school in Khachmaz village in Nukha and worked there for 2 years.

At that time, seminary graduates did not have the right to teach in city schools and so Rashid bey won a place in the fourth year at the Tbilisi Alexandrovski Institute for Teachers, graduating from there in 1893 and earning the right to teach in city schools. He taught until 1899 and by invitation worked at the Gori Seminary as a teacher of Azerbaijani and sharia for 17 years. During that time he wrote two textbooks: Kindergarten (1899) and Basiratul-etfal (The Quickness of Children) (1910).

Other well-known graduates, Suleyman Sani Akhundov (1875-1939), Rashid bey Efendiyev (1863-1942), Farhad Aghazadeh (1880-1931)

Other well-known graduates, Suleyman Sani Akhundov (1875-1939), Rashid bey Efendiyev (1863-1942), Farhad Aghazadeh (1880-1931)

Rashid bey Efendiyev joined people’s struggle for their mother tongue and wrote that mother tongue was key to learning the sciences. He said that it was impossible to learn foreign languages without speaking one’s mother tongue.

He also became a famous writer. He wrote plays: House of Blood, The Virtue of a Beard, If Neighbours are True, Even a Blind Girl Will Be Married, The Price of One Hair, Rose, Toothache and many poems and stories. Rashid bey spoke fluent Arabic and contributed a great deal to ethnographic studies. He wrote a number of works on the ethnography of the Nukha and Qutqashen regions.

Much has been written about the lives, work and services to the nation of Gory Seminary graduates. Foremost among them are the world famous composer and founder of Azerbaijani national music, Uzeyir Hajibeyov, the composer Muslim Magomayev, the great democrat, writer and publicist Jalil Mammadguluzadeh, the politician Nariman Narimanov and the writer-teacher Suleyman Sani Akhundov. They were all graduates of the Gori Seminary and are still the pride of the Azerbaijani nation.

About the author: Garatel Gafarova is Head of the Exposition Department of the National Education Museum at the Ministry of Education. She is the author of research into the history of education in Azerbaijan.