Student Academy Award winner

It’s interesting that Elmar Imanov was among three foreign filmmakers to be awarded at the most prestigious 39th Student Academy Awards of the American Film Academy. Actually, Elmar was the first Azerbaijani director to receive such a prize. So his compatriots were quite curious and many came to watch his Oscar-winning film.At the Park Bulvar screening on 6 October, as well as the production crew, there were the media, film critics, students, young actors and representatives of the German Embassy to Azerbaijan. The German contingent’s presence wasn’t by chance. Originally from Azerbaijan, Elmar Imanov has been in Germany for a few years. He graduated from the International Film School Cologne. Actually The Swing of the Coffin Maker was his graduation project and he decided to send it to a number of film festivals. He struck lucky – the film was not only invited to the American Academy Awards, but was also among the winners. As the young director himself admitted, a lot of work went into the achievement. Although Germany was the production country, all the filming was done in Azerbaijan. Thus the film crew, mainly Germany-based specialists, travelled here several times.

A simple but vital drama

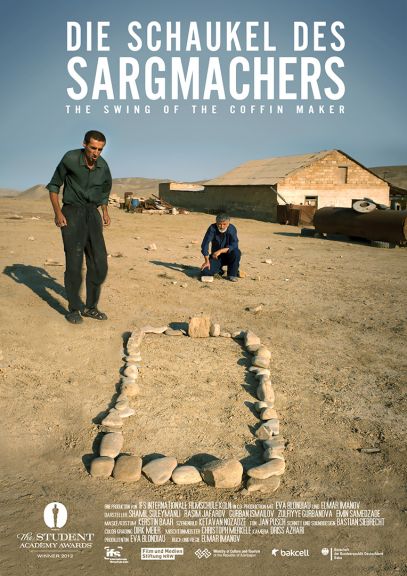

The Swing of the Coffin Maker is a drama by genre and the plot is very simple, but very vital. Perhaps this is what drew such appreciation from both audience and jury for Elmar’s work. The plot centres on 60-year old Yagub who lives with his adult son Musa in a small house in a desolate place. They lead a solitary life. Musa, mentally disabled and limited in his motor skills, assists his father with his work. Yagub is a coffin maker and earns his living by making coffins for Christians, mainly for Georgians and Russians. When faced with his son’s clumsiness he often reacts angrily – and with a beating. He is severe, tough, straightforward and intractable. He always asks something of his son just once. In the event of a refusal or failure to understand, the father’s hand flies up threateningly, his voice is raised and curses fly from his mouth.One day Musa falls ill and Yagub takes him to a doctor. This doctor diagnoses Musa as having a fatally progressive illness, which will kill him within a month. The father listens silently to the doctor’s verdict, gives him some money and returns home to take measurements from his son for the grave and marks Musa’s future grave out in stones. The son sees the shape on the ground and seems to understand for whom it is intended. He leaves the house for a whole day. Over the hill there is a small, muddy lake, formed after rain. Musa undresses and runs into the water in an act of ablution, to appear before the Lord as he should, with clean body and soul… On his return, strangely, he does not receive the usual caning as punishment for his misconduct, and Yaqub comes to an unexpected decision.

He hires a prostitute to make his son’s last days as pleasant as possible. He wants his son to experience before death one of the pleasures of life unfamiliar to the sick and poor. So, it seems that when Musa is afflicted by a fatal illness, the father’s emotional numbness slowly dissolves as he tries to help his son to enjoy his remaining days.

Hearing that the doctor had been dismissed and arrested for bribery, Yagub takes his son to see another one. The new doctor, a young man who flatly refuses the traditional payment, is truly embarrassed. He apologises for his arrested colleague and talks of a misdiagnosis. These words stir something inside the father, as if he has been asleep all the while. The film’s closing shots are of father and son sitting in the back of the car taking them home. Musa rests his head happily on his father’s shoulder. Yaqub’s eyes shine with the first glimmers of light. His severe, frozen features soften and the light in his eyes breaks into the first sparks of a soul returned to life. The swing of the undertaker, dowsing Yagub and Musa with deathly cold, brings the two of them to the light…

The audience at the film presentation were appreciative and there was special interest from young filmmakers and students. They questioned the film crew as well as sharing their feelings from the screening. The actress Zulfiya Gurbanova, who played the prostitute in the film, said:

This film showed me and told me a lot. Isn’t there domestic violence in our lives? In the film the father treats his son very badly. But when we see the father feeding his son, the light from the son’s eyes wakes him up. And it’s very good that there is little dialogue. We have all seen many films with empty, meaningless speech. Here there are gestures; the eyes and face do the talking. So it’s easy for everyone to understand the film.

According to the film’s producer Eva Blondiau, its main message is one of humanity and kindness. Everyone takes the film’s meaning in their own way. But they cannot escape the message of love.

A new country with a new landscape for audiences across the world

As director Elmar Imanov told Visions, the film was shot in a region of Azerbaijan, on the Absheron peninsula with its desert landscapes. He shared his thoughts about the filming process and why he decided to make the film in Azerbaijan and not in Germany for example.How did you come up with the idea for the film? What is its message?

The inspiration was Chekhov’s story, Rothschild’s Violin. Let me stay silent on the second question. I just prefer not to answer it. In other words, I filmed what I felt and I think different people can find different answers from it.

What was the budget for the film, if that’s not a secret?

No, of course it’s not a secret. In total we spent about 40,000 Euros. The Foundation of North Rhine – Westphalia allocated 22,500 Euros, Bakcell – 5,000 Euros and the International Film School Cologne – 12,000 Euros.

Why did you decide to shoot The Swing of the Coffin Maker in Azerbaijan, not in Germany?

Azerbaijan is primarily a new country with a new landscape for audiences across the world. I made a number of shorts while studying at the Film School, including some produced in Baku with Azerbaijani casts. In 2008 we invited a remarkable actor from Baku, Shamil Suleymanli, for the major role in my debut film about emigrants. Later, we invited him to play in The Swing of the Coffin Maker. I have to say that while I was here in Azerbaijan looking for a suitable location, our production team discovered new sides to the country. I took as much as I could from the experience and tried to bring a special mood to the film.

Where did you find the location? And why do your heroes live apart from people, society?

As I mentioned, we visited many places in Azerbaijan, from Balakan to Astara, to find a suitable place. But nowhere could we find exactly what we wanted. Finally we arrived in Gobustan where, on the way to Shemakha, we discovered a place with an isolated house. It was not quite what we wanted, but we had no time to continue our search. The heroes’ lonely life is to be expected. Rarely in life do we meet coffin makers and, even more rarely, their friends. Remember, all those who are in any way associated with death, like witches, warlocks, executioners –have all generally lived apart. Society has always been afraid of them. And they, being touched by another world, had no wish to be close to society. I confess that my film is something of an echo from history, taken from Chekhov’s Rothschild’s Violin.

What else would you like to make a film about, here in Azerbaijan? Have you already got an idea for the next one?

There is a concept. But I’m going to shoot my real debut film in Germany. I will do something in Azerbaijan, but I need to prepare plot and finance. So I need some time.

What do you think about cinematography in Azerbaijan? What do you think our young filmmakers need to work on to improve their skills?

I live in Germany, so it’s a little difficult for me to assess the real state of Azerbaijani cinematography. But I’ve heard about the newly-created Union of Cinematographers of the Republic of Azerbaijan. In fact, cinematography has developed quite a long way. But despite some good approaches there are some problems. There should be a strong film school attached directly to production studios and the processes of live filming. It is the case that some talented directors return to Azerbaijan after studying in Moscow for example, but are frustrated in their projects. Another point is that filmmakers should be paid more than they are now, that could prevent an outflow of talented filmmakers. They could stay here in Azerbaijan and share their experience with young filmmakers. A good film school is one where there are opportunities to make films by students and for students. I would recommend young filmmakers to work hard and try to produce films as much as possible, even very low budget films. Also it’s very important and helpful to do joint projects, to discuss concepts together, to make new contacts and to be able to call on assistance. And they shouldn’t be afraid of sending their films to international film festivals. Filmmakers need very good networks. We filmmakers are not artists or writers who work alone. We don’t make films alone; we need assistance from others. And we depend on them. I think it’s a key issue to help and be helpful.

What feelings did you have when you were awarded the Student Oscar?

Oh, I was immensely touched, delighted and excited. Such a good feeling!