Pages 20-25

Pages 20-25by Ian Peart

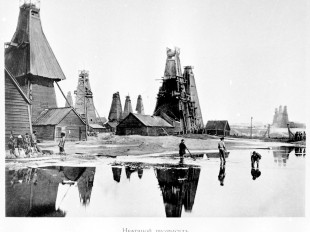

On 24 July 1949, 60 years ago to the day that this is written, an intrepid group of oil workers began to drill into the bed of the Caspian Sea. They were some 42 kilometres south-east of the Absheron Peninsula - that “beak” of Azerbaijan which juts into the world´s biggest lake - and balanced precariously on an underwater range now known as Neft Dashlari, or Oil Rocks. The site was given its name when drilling got down to 1,100 metres and on 7 November 1949 sent back a gush of the black gold they had risked their lives for.

The first expedition had ventured out there a year earlier and built small living quarters and power generation facilities onto the rocks. Then Mikhail Kaverochkin had set his team of drillers to work, guided by geologist Agaqurban Aliyev´s nose for oil.

The construction that followed demanded imagination and true heroism. Some would say that Oil Rocks is an industrial wonder of the world; that only the politics of the Cold War denied it and its creators the international recognition it deserves. Flying over it in 2001, on the way to a more modern platform, I could see the effects of the turmoil of the post-Soviet period.

There were many breaks in the vast web of roads and platforms below (240 kilometres of them), where whole sections had collapsed into the sea. But there was enough to arouse that itch of curiosity familiar to many who visit this country full of intriguing nooks and crannies. It took six years to organise a visit to Neft Dashlari but persistence paid off in October 2007. A 12-minute helicopter flight from Pirallahi (Artyom) Island set us down on this oil-city-in-the-sea. As we watched the helicopter shuttle off over the trestle-supported roadways, we all felt the thrill of the exotic - not quite the exotic usually associated in western minds with the east - but exotic nonetheless.

A short bus ride to the social hub of the network and our eyes opened wider. Was this really a nine-storey accommodation block before us – its bulk rising above rocks 40 kilometres from the nearest land? Surely this park - with grass, flowers, trees and birdsong - was a mirage? Were there really around 2,000 people (400 of them women) working here at any one time? Yes, working two weeks on and two weeks off, so, in all, the site was providing work for 4,000.

As we learned, the peace of that calm October day stood in contrast to some of the conditions faced by the pioneers at Oil Rocks. Those familiar with Baku understand why it is known as the City of Winds, and it is not difficult to imagine what those winds are capable of on the open sea. Close by the now ceremonial valves marking the site of first drilling and first oil is a memorial to 21 men who went down with their ship in a storm - the names include one Mikhail Pavlovich Kaverochkin, who led the first team of drillers at Oil Rocks.

Even with much of the pioneer work complete, the sea and the elements refused to yield and constantly demanded courage, resolve and unity from those who battled to keep the oil and gas flowing. Pipelines to the shore, opened in 1983, were laid to avoid the problems faced by tankers in foul weather - storms which could at the least halt production and at the worst take lives. Of the 240 kilometres of causeways, only 110 kilometres or so are still in use – nature having taken quick advantage of the economic problems which accompanied the decline and fall of the Soviet Union.

In such a location, conditions are always going to be tough, and there were still many remnants of Soviet-era decay, but they seemed to have stimulated in people a determination not to be beaten and a pride in overcoming adversity. We met many who had devoted long working lives to Oil Rocks - one man was in his 50th year of service there - and they were seeing a turnaround. Accommodation was being refurbished and new reserves were being discovered, enough so far to last another 30 years, we were told.

Oil Rocks is a modern legend - myriad stories circulate about this place and it has fevered the brains of painters, writers, film directors and musicians down the years. Tahir Salahov, perhaps Azerbaijan´s most celebrated painter, managed to temper the conformity of Socialist Realism by injecting a human response. His depictions of the people operating Oil Rocks convey somehow both their heroism and the toll taken by arduous work -The Shift is Over is one such example.

Qara Qarayev, equally renowned composer, was commissioned to write the score for a documentary film about the sea-borne oil workers. Taken out to Oil Rocks for some location setting, he was so impressed by the scene that he insisted on staying there to finish the composition. Azerbaijan´s most famous jazzman, Vaqif Mustafazadeh, composed a piece Oil Rocks - typically of this flamboyant individualist it is a jaunty, upbeat tune, notes tumbling over each other, perhaps in exuberant release from painstaking labour.

Internationally, the best known depiction of Oil Rocks is also the least realistic. A film crew including Pierce Brosnan and Sophie Marceau arrived in Baku in 1999 to act out scenes for the James Bond film The World Is Not Enough. The hero is seen speeding through the forest of nodding donkeys (since dramatically thinned out) in the Bibi Heybat oil field in typically flash sports car. Oil Rocks suffers harsher treatment, being sliced up by a saw-wielding helicopter and then blown up (thankfully, only in studio model form).

It is not fashionable in these environmentalist times to celebrate the achievements of the oil and gas industries. They are associated, in many western minds at least, with pollution, carbon footprints and all the rest. Conditions on Oil Rocks, despite the improvements taking place, were still some way short of ideal.

Sitting in the comfort of an apartment appropriately heated and cooled, typing this out on a plastic keyboard and listening to a CD of Vaqif Mustafazadeh´s musical impressions - all thanks to the oilmen - I can´t help thinking with gratitude and awe of the struggle waged by Mikhail Kaverochkin and those who have followed him to bring this power from deep below the surface of the Caspian Sea. Let´s hope the elements relent to allow Oil Rocks, this wonder of the industrial world, to enjoy a happy 60th birthday.