There is an Eastern music culture apart from European music and, as people of the East, if we neglect Eastern music in musical education we will not fulfil our cultural task honourably. The tar is the most important, most valuable musical instrument, allowing us to develop Eastern musical education.

- U. Hajibeyov the great Azerbaijani composer of the first Eastern opera, brilliantly combining musical cultures of East and West.

The tar in brief

The tar is a stringed musical instrument plucked with a mizrab, a plectrum. Its exact origins are unknown but it is quite widespread through the Caucasus, Iran and Central Asia. The Dutar (two stringed), sitar (three stringed), çahar tar (four stringed), panj tar (five stringed) and shesh tar (six stringed) are different types of primitive tar. Among them, the best-known was the 5 stringed tar. The instrument has three main parts – a figure-eight-shaped body, neck and head. From 1870-75, the Azerbaijani tarzan (tar player) Sadigjan (Mirza Sadig Asadoghlu) improved the instrument by adding 6 more strings. The Azerbaijani tar has 11 strings, a larger body and shorter neck. Sadigjan also raised the playing position from the knees to the chest.

Father of the Tar

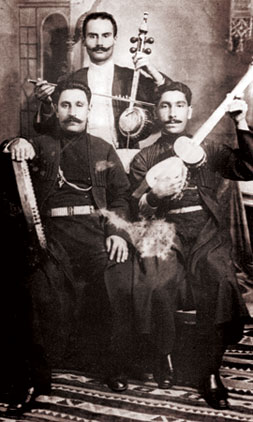

In the 19th century, Shusha was the conservatoire of the Caucasus. Every summer, celebrated musicians, composers, artists, dramatists and poets from all over the Caucasus assembled in Shusha and played in Eastern concerts. There were regular literary and musical gatherings at which prominent artists and musicians discussed literature and played mugham. One of these assemblies, Mejlisi Uns (Meeting of Friendship), was founded by Azerbaijani poet Khurshidbanu Natavan and continued from 1864-1897. Another well-known assembly was the Mejlisi Feramushan (Meeting of the Forgotten). It was here that the people of Karabakh discovered Mirza Sadig, the master of the tar. Sadigjan was born into the poor family of a watchman in Shusha, Karabakh’s cultural heart. As a teenager, he took vocal lessons but lost his voice at the age of 18. He then played pipe, kamancha and, eventually, tar. By his mid-20s, he was already well-known in the South Caucasus and neighbouring regions. In the 1890s he founded a musical ensemble which included prominent folk singers and musicians. He participated in the first Eastern Concert in 1901, giving the first solo tar rendering of the mugham composition Mahur. This innovative tar player changed the structure of the tar between 1870 and 1875. He improved it by adding six more strings- ‘ringing’ and melody strings which enabled the tar to play all mughams. He also removed unwanted tones by inserting a wooden pedestal into the body to reduce tension between the body and neck; it also creates a vibrato effect. Before Sadigjan, the tar was played on the knees, after reducing the tension he began to play it on the chest.

The Azerbaijani tar serves as both accompanying and solo instrument in a mugham performance; solo performance is possible due to Sadigjan’s innovations, which also had an effect on the singing. Mugham singing techniques responded to the new technical possibilities of the tar. The changes were so marked that musicians know Sadigjan as ‘the father of tar’.

An instrument against repression

In the 1900s, the tar endured its most difficult trials. Indifference to national culture and traditions, and the rejection of national art forms were commonplace in the early 20th century. Representing national musical culture, the tar was exposed to pressure and repression during the Soviet Union’s Cultural Revolution, anti-tar sloganising was not uncommon. In those days, the Azerbaijani intelligentsia was split: one section saw the instrument as old-fashioned, even feudal, and unsuited to modern times; others regarded it as a valuable part of national musical culture and thought it could be incorporated into new musical forms.

To sing or not to sing?

An article published in the second issue of the magazine Revolution and Culture in 1929 was headed Tar Removed from the Conservatoire and declared:

The tar has no future and cannot have one. The tar will remove itself from the stage.

The anti-tar campaign was even waged in the literature of the period. People’s Poet Suleyman Rustam, who was chief editor of the newspaper Literature and director of the Azizbekov Azerbaijan State Academic Drama Theatre wrote Do Not Sing Tar:

Shut up, shut up, enough, shut up, hey tar!

The proletarian does not want you to play “Qatar”!

Do not sing tar, do not sing tar

You cannot sing the “International”

Do not sing tar, do not sing tar,

The proletarian does not like you, tar!

Such attacks infuriated other prominent artists like Uzeyir Hajibeyov, Mikayil Mushfiq and Afrasiyab Badalbeyli. They rose to the tar’s defence of tar despite repression and prohibition.

In answer to Suleyman Rustam’s Oxuma tar, the poet Mikayil Mushfiq wrote his celebrated poem Oxu Tar:

Sing tar, sing tar!

Who would forget you?

The idea of the poem is so comprehensive and rich that it would be wrong to limit it to simply a defence of the tar. Mushfig not only defended the tar, he asserted that it was not old fashioned but sought modern meaning in the classical cultural heritage. With the tar as symbol, the poet defended the spiritual values and traditions of national culture. Vivid in its imagery, the poem is also philosophical, with strong social commentary, right from the outset. The beauty of the poem lies in its ideological depth, emotional richness and philosophical understanding of mugham. Unlike the tar’s opponents, Mushfiq hails it a fiery art of the Azerbaijani people, expressing the painful and happy moments of life so masterfully:

Sing tar, Sing tar!

Let me listen to lovely poems on your sound.

Sing tar, a little more!..

Let me splash this song, water for my glinting soul.

Sing, tar! Who would forget you?

The people’s bittersweet,

Fiery art!

The author poses the tar as a symbol of national music, as a reflection of the nation’s character, psychology and emotions. It serves not only kings and the elite, but all layers of society.

While the poet defended the tar against repression he could not save himself. He was soon subjected to criticism and slander. Mushfig was arrested in 1937, charged with treason by the Soviet authorities as an enemy of the state and executed in 1939 in Bayil prison near Baku, aged 30. In 1956 he was posthumously exonerated.

Years later, Suleyman Rustam realised his mistake and repented in a new poem:

No, No, I am convinced, no vote on the tar,

It is impossible to tire of its native voice.

The tar in Azerbaijani opera

The Azerbaijani opera is generally a mugham opera, in which the tar leads the orchestra and mugham is the basis of the aria, naturally accompanied by the tar. Uzeyir Hajibeyov explained its importance:

If I wanted to promote the tar simply as a national instrument then I could also add the kamancha to orchestra. But that was not necessary, as the violin can perform the task more efficiently in operas based on Eastern music. The same cannot be said of the tar, its timbre is an innovation in opera. Its finest sounds are extremely pleasing, that is why I feel it necessary to include it in the orchestra.

Hajibeyov’s first mugham opera, Leyli and Mejnun, established the fundamentals for Azerbaijani opera. After the successful performance in 1908 he wrote Asli and Karam, Sheykh Sanan, Rustam and Sohrab, and Shah Abbas and Khurshid Banu. These mugham operas with tar were played to fascinated audiences despite criticism. No repression or prohibition could cast a shadow over the triumph of the tar.

Brief note to tar neophytes

When you listen to the tar, close your eyes and let it to speak to your soul. You will take a mysterious journey touching the temperament of the Caucasus and the relaxing serenity of Eastern culture. Allow the melancholy of the tones draw you into the nostalgia of the past, of something valuable but inaccessible. In the tar’s plaintive melody you will hear the emotional desire of lovers, the struggle of combatants, and the story of the dervish search for the meaning of life. It will be a unique journey to an inner world summoning feelings of retained naivety.

.jpg)