Sara Oghuz Nazirova is an Azerbaijani writer and art critic. The author of novellas, stories, plays and film scripts, she was awarded the title Honoured Arts Worker of Azerbaijan in 2012. One of her most recent projects, the film ‘Stepping over the Horizon’, features the work of five of the artists from the Absheron School of painting, who are the subject of an article on page..

. Born in the picturesque town of Oghuz in north-west Azerbaijan, Sara writes warmly but without sentiment about life in the provinces and in Baku. She is no writer of strident prose, but ‘speaks to her reader in a whisper’, to quote fellow author Menzer Eynullayeva. The story whispered below, ‘When the Grass Grows’, was first published in Azerbaijani in 1983 and came out in English in 2009 in Sara Oghuz Nazirova’s ‘Selected Works’.

by Sara Oghuz Nazirova

The woman stretched out on the operating table thought the schoolgirl at the window was a dreadful bird. Sensing that the patient was looking at her, the girl jumped down. She soon wanted to climb back up to the window, though, and this time it seemed to the woman that the bird was going to flap its wings and jump on her. It turned into a shadow, and then into scraps of rag and disappeared. Aware of the eyes of the woman fixed on her, the girl remained motionless, thinking that those eyes didn’t seem to see at all. Next, the woman felt a strange bird land on her chest. Dark shadows twisted round her head and pressed their weight on her. The girl thought the woman’s arms and legs, sticking out from the white sheet, looked like melted wax that has run into pools, pools formed by the tear drops of her dark yellow face. On either side of the wax pools rested hypodermic syringes and rubber tubes.

Two flushed women in white coats bustled around the patient, snapping fearfully: ‘Breathe, breathe! What are you doing, Sister Shukufa? You are choking the child, breathe!’ And they slapped the woman’s increasingly fading face.

Her nose pressed against the window pane, the girl thought something important was about to happen. It was such an important event that she could feel her heart beat in her palm, as though she held in her hand not the iron window frame but a baby sparrow fallen from its nest. This had happened a year before too, when she was taking an exam. A heaviness, something like pain had risen up her gullet from the pit of her stomach and concentrated in her throat. Something in the scene that she was watching made her flesh creep. As soon as something blue-red and unfamiliar splashed the doctor’s hand, the white-coated nurse smiled and bent to say something to the patient. It seemed to the girl that the wax pool would never open her eyes. It seemed to stop melting. But her head was stirring. Her eyelashes parted. Her gaze was fixed on the doctor’s hands. The little girl couldn’t believe her eyes. The sound of laughter ‘Uhu, uhu’ could be heard from the pool of wax. Then she rested her head back down in the white sheets.

The school girl jumped down from the window. She wanted to run away and talk to someone, but didn’t have the strength to run, her legs failed her. The world seemed to have changed. Everything had changed. The yard of the hospital, the sun hanging in the sky, she herself… It had all become a little more ordinary, a little nearer. Whatever might happen after that, nothing would change. She would not grow up though she lived to be one hundred. She wanted to weep, realizing the unchanging nature of the colourful world today and tomorrow, the stagnation of a world that had changed, that had kept something mysterious somewhere in the distance, far away from her, and which now had become clear and ordinary. Old Tutu sat on the stool in the hospital yard, her thin body lost in her loose dress. Instead of asking Old Tutu and Hamid the Lorry for gifts for being the bearer of good news, the medical orderly uttered words of consolation: ‘Don’t pay attention. This time the baby will live, God willing! Tell her not to breastfeed the baby, that’s all. Take the baby and give it to one of your distant relatives. Don’t let the baby see its mother,’ she said.

Old Tutu did not answer; she remained on her stool, swaying back and forth as if on a swing. From time to time she sobbed.

When Hamid the Lorry heard that he had a son, he sprang to his feet. In an instant he searched for money in all his pockets. He pulled a cigar out of his pocket which he had already put back once, and lit up. He took a few steps towards the hospital and came back again. He picked up the schoolgirl like a parcel and got into the cabin of his lorry. He drove the lorry straight to the schoolyard and shouted: ‘Get on the lorry, all of you!’

As the shabby old lorry rocked up and down the flinty roads with the excited children laughing and shouting, Hamid the Lorry thought he had gathered all the good he had done in his life onto his lorry and was taking it somewhere. He thought he had loaded the joy of the world onto his lorry. As the vehicle shook, it made Hamid the Lorry’s rough, lopsided face tremble at the wheel, teardrops trickling out of his deep-set eyes down the wrinkles of his face. The schoolgirl sitting in Hamid the Lorry’s cabin looked at his black-grey face and his dark eyes flashing with light. She remembered what her mother had told her about Aunt Shukufa and Hamid the Lorry. Hamid and his lorry had survived all the theatres of the war. As he had nobody waiting for him, he did not return home straightaway, and as the lorry that he drove during the war had been allocated to the region where he lived, he drove it back home.

The machine stood still more than it moved. In spring and summer, autumn and winter, Hamid the Lorry could be seen lying under his vehicle, repairing one part, then another.

‘Hey Hamid, instead of getting on the machine, the machine gets on you,’ the people used to make fun of him.

When the Vehicle and Tractor Station got a new Gaz-51 lorry everybody congratulated Hamid and said he wouldn’t get stuck in the muddy road any more in his Palturka.

Hamid took a deep puff of his cigarette, stuck his elbow out of the window and said: ‘A man should have one horse, one wife and one cap.’

When Hamid came home after the war, he was the most famous man in the surrounding villages. When a dust cloud covered the road, they wouldn’t say a car was coming, they would say ‘Hamid’s coming’. When the children’s dreams came true and they climbed into Hamid’s lorry, when the girls of the village travelled in the Palturka as brides, the threat of hunger and danger of the war passed away. Perhaps that was why slim-waisted, graceful, elegant Shukufa Khanim married Hamid, whose age and background were unknown. Perhaps it was because her young husband had died and she herself had caught lung disease from him. Who would marry a sick woman? Maybe, it was because the war had swept away all the men that she married him!

As the Palturka headed straight for the breast of the mountain, stirring up a thick veil of dust, the girl sitting in the cabin suddenly thought that Hamid would drive his lorry till it stuck in the snow, tinted red by the setting sun. As she looked at his hands gripping the steering wheel, she remembered Aunt Shukufa’s conversation with her mother.

‘Hamid’s palm is like a bird’s nest, Sister Saltanat! Don’t blame me! I have not broken my promise. By God, by the end of the year my love for Jabrail had gone. While he floundered in his bed till morning, drenched in sweat like water, crying out in fear that it was me, me who had made him an outlaw, I no longer wanted to live. When I did venture out, I was a washed-out rag from hearing people blame me so much. By God, I have enjoyed my life with Hamid, Sister Saltanat. Every morning when I pour water for Hamid to wash his hands and face, I think, God, how those two hands can offer so much care!’

Hamid’s children passed away. They would be infected by their mother within three days of their birth and would soon be lost. One of them lived six months. Hamid had high hopes for him, but he didn’t live.

No, today everything begins all over again. Today Hamid’s fourth child has been born. He won’t let anything happen to the child. He will take the child to the other end of the world. He won’t let anything bad happen to the child. Today the snow of the gigantic mountain lies before him, snow that is visible in the clear light of day. He has his Palturka full of joy, he has a tiny new-born baby whom he has not yet seen, he has his beautiful Shukufa. He has all these joys, mixed up together today.

‘Sister Saltanat, don’t be offended by what I say. Have mercy on yourself. You have small children. Old Tutu never opens anybody’s door as she is afraid she might infect them. Don’t you see that the woman lost her mountain of a son? Don’t you see that Shukufa has given birth with so much trouble, but alas her cradles remain empty?’

‘Shukufa is a good woman, Ruhsara.’

‘I’m not saying she isn’t. Everybody says that she is a graceful woman. Have pity on your children. I say they are quite small. If you are nursing her, you may infect them. And you yourself are young. Couldn’t you find anybody else to nurse her?’

‘May God destroy the house of whoever is to blame for this! Shukufa is a lovely woman and Tutu is a woman of noble pedigree.’

‘Yes, I agree with you, she is a woman of noble pedigree. But didn’t she know when she married her daughter to Jabrail that he ran away and hid in a well to avoid the war?’

‘He was Shukufa’s cousin.’

‘He could be God’s cousin but not his uncle’s son. Did he turn out nicer than other boys? Was he better than everybody? If trouble comes to all, it is not trouble but a wedding, they say.’

‘They loved each other since they were children. They loved each other very much. It was because of Shukufa that he ran away from the war, that damn man. He was only a child when he was called up.’

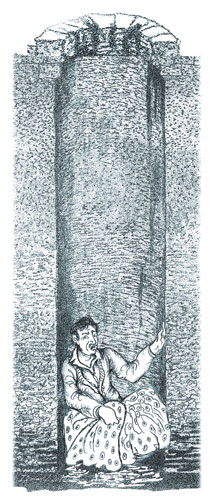

‘He dug his own grave. He went down the well, put on a woman’s skirt and lay there. He couldn’t make a husband for Shukufa for six months. It’s no fun not to see sunlight for two years.’

‘It’s not good to speak of the dead, Ruhsara.’

‘Let the dead go to hell! He gained nothing for this life or the next. And, he got Tutu into trouble. Before mourning ends for one, it begins for the other. An inch of grass has grown on his grave, but the tragedy of his deeds has not finished – Shukufa’s health is too bad,’ said Saltanat and wiped her eyes.

‘It’s the time when the grass grows. If she can survive this spring, she will live till next spring,’ Ruhsara said, lowering her voice.

Sitting by her mother and washing mint, the schoolgirl suddenly thought of vast, dark green cornfields licked by the wind.

. Born in the picturesque town of Oghuz in north-west Azerbaijan, Sara writes warmly but without sentiment about life in the provinces and in Baku. She is no writer of strident prose, but ‘speaks to her reader in a whisper’, to quote fellow author Menzer Eynullayeva. The story whispered below, ‘When the Grass Grows’, was first published in Azerbaijani in 1983 and came out in English in 2009 in Sara Oghuz Nazirova’s ‘Selected Works’.

by Sara Oghuz Nazirova

The woman stretched out on the operating table thought the schoolgirl at the window was a dreadful bird. Sensing that the patient was looking at her, the girl jumped down. She soon wanted to climb back up to the window, though, and this time it seemed to the woman that the bird was going to flap its wings and jump on her. It turned into a shadow, and then into scraps of rag and disappeared. Aware of the eyes of the woman fixed on her, the girl remained motionless, thinking that those eyes didn’t seem to see at all. Next, the woman felt a strange bird land on her chest. Dark shadows twisted round her head and pressed their weight on her. The girl thought the woman’s arms and legs, sticking out from the white sheet, looked like melted wax that has run into pools, pools formed by the tear drops of her dark yellow face. On either side of the wax pools rested hypodermic syringes and rubber tubes.

Two flushed women in white coats bustled around the patient, snapping fearfully: ‘Breathe, breathe! What are you doing, Sister Shukufa? You are choking the child, breathe!’ And they slapped the woman’s increasingly fading face.

Her nose pressed against the window pane, the girl thought something important was about to happen. It was such an important event that she could feel her heart beat in her palm, as though she held in her hand not the iron window frame but a baby sparrow fallen from its nest. This had happened a year before too, when she was taking an exam. A heaviness, something like pain had risen up her gullet from the pit of her stomach and concentrated in her throat. Something in the scene that she was watching made her flesh creep. As soon as something blue-red and unfamiliar splashed the doctor’s hand, the white-coated nurse smiled and bent to say something to the patient. It seemed to the girl that the wax pool would never open her eyes. It seemed to stop melting. But her head was stirring. Her eyelashes parted. Her gaze was fixed on the doctor’s hands. The little girl couldn’t believe her eyes. The sound of laughter ‘Uhu, uhu’ could be heard from the pool of wax. Then she rested her head back down in the white sheets.

The school girl jumped down from the window. She wanted to run away and talk to someone, but didn’t have the strength to run, her legs failed her. The world seemed to have changed. Everything had changed. The yard of the hospital, the sun hanging in the sky, she herself… It had all become a little more ordinary, a little nearer. Whatever might happen after that, nothing would change. She would not grow up though she lived to be one hundred. She wanted to weep, realizing the unchanging nature of the colourful world today and tomorrow, the stagnation of a world that had changed, that had kept something mysterious somewhere in the distance, far away from her, and which now had become clear and ordinary. Old Tutu sat on the stool in the hospital yard, her thin body lost in her loose dress. Instead of asking Old Tutu and Hamid the Lorry for gifts for being the bearer of good news, the medical orderly uttered words of consolation: ‘Don’t pay attention. This time the baby will live, God willing! Tell her not to breastfeed the baby, that’s all. Take the baby and give it to one of your distant relatives. Don’t let the baby see its mother,’ she said.

Old Tutu did not answer; she remained on her stool, swaying back and forth as if on a swing. From time to time she sobbed.

When Hamid the Lorry heard that he had a son, he sprang to his feet. In an instant he searched for money in all his pockets. He pulled a cigar out of his pocket which he had already put back once, and lit up. He took a few steps towards the hospital and came back again. He picked up the schoolgirl like a parcel and got into the cabin of his lorry. He drove the lorry straight to the schoolyard and shouted: ‘Get on the lorry, all of you!’

As the shabby old lorry rocked up and down the flinty roads with the excited children laughing and shouting, Hamid the Lorry thought he had gathered all the good he had done in his life onto his lorry and was taking it somewhere. He thought he had loaded the joy of the world onto his lorry. As the vehicle shook, it made Hamid the Lorry’s rough, lopsided face tremble at the wheel, teardrops trickling out of his deep-set eyes down the wrinkles of his face. The schoolgirl sitting in Hamid the Lorry’s cabin looked at his black-grey face and his dark eyes flashing with light. She remembered what her mother had told her about Aunt Shukufa and Hamid the Lorry. Hamid and his lorry had survived all the theatres of the war. As he had nobody waiting for him, he did not return home straightaway, and as the lorry that he drove during the war had been allocated to the region where he lived, he drove it back home.

The machine stood still more than it moved. In spring and summer, autumn and winter, Hamid the Lorry could be seen lying under his vehicle, repairing one part, then another.

‘Hey Hamid, instead of getting on the machine, the machine gets on you,’ the people used to make fun of him.

When the Vehicle and Tractor Station got a new Gaz-51 lorry everybody congratulated Hamid and said he wouldn’t get stuck in the muddy road any more in his Palturka.

Hamid took a deep puff of his cigarette, stuck his elbow out of the window and said: ‘A man should have one horse, one wife and one cap.’

When Hamid came home after the war, he was the most famous man in the surrounding villages. When a dust cloud covered the road, they wouldn’t say a car was coming, they would say ‘Hamid’s coming’. When the children’s dreams came true and they climbed into Hamid’s lorry, when the girls of the village travelled in the Palturka as brides, the threat of hunger and danger of the war passed away. Perhaps that was why slim-waisted, graceful, elegant Shukufa Khanim married Hamid, whose age and background were unknown. Perhaps it was because her young husband had died and she herself had caught lung disease from him. Who would marry a sick woman? Maybe, it was because the war had swept away all the men that she married him!

As the Palturka headed straight for the breast of the mountain, stirring up a thick veil of dust, the girl sitting in the cabin suddenly thought that Hamid would drive his lorry till it stuck in the snow, tinted red by the setting sun. As she looked at his hands gripping the steering wheel, she remembered Aunt Shukufa’s conversation with her mother.

‘Hamid’s palm is like a bird’s nest, Sister Saltanat! Don’t blame me! I have not broken my promise. By God, by the end of the year my love for Jabrail had gone. While he floundered in his bed till morning, drenched in sweat like water, crying out in fear that it was me, me who had made him an outlaw, I no longer wanted to live. When I did venture out, I was a washed-out rag from hearing people blame me so much. By God, I have enjoyed my life with Hamid, Sister Saltanat. Every morning when I pour water for Hamid to wash his hands and face, I think, God, how those two hands can offer so much care!’

Hamid’s children passed away. They would be infected by their mother within three days of their birth and would soon be lost. One of them lived six months. Hamid had high hopes for him, but he didn’t live.

No, today everything begins all over again. Today Hamid’s fourth child has been born. He won’t let anything happen to the child. He will take the child to the other end of the world. He won’t let anything bad happen to the child. Today the snow of the gigantic mountain lies before him, snow that is visible in the clear light of day. He has his Palturka full of joy, he has a tiny new-born baby whom he has not yet seen, he has his beautiful Shukufa. He has all these joys, mixed up together today.

‘Sister Saltanat, don’t be offended by what I say. Have mercy on yourself. You have small children. Old Tutu never opens anybody’s door as she is afraid she might infect them. Don’t you see that the woman lost her mountain of a son? Don’t you see that Shukufa has given birth with so much trouble, but alas her cradles remain empty?’

‘Shukufa is a good woman, Ruhsara.’

‘I’m not saying she isn’t. Everybody says that she is a graceful woman. Have pity on your children. I say they are quite small. If you are nursing her, you may infect them. And you yourself are young. Couldn’t you find anybody else to nurse her?’

‘May God destroy the house of whoever is to blame for this! Shukufa is a lovely woman and Tutu is a woman of noble pedigree.’

‘Yes, I agree with you, she is a woman of noble pedigree. But didn’t she know when she married her daughter to Jabrail that he ran away and hid in a well to avoid the war?’

‘He was Shukufa’s cousin.’

‘He could be God’s cousin but not his uncle’s son. Did he turn out nicer than other boys? Was he better than everybody? If trouble comes to all, it is not trouble but a wedding, they say.’

‘They loved each other since they were children. They loved each other very much. It was because of Shukufa that he ran away from the war, that damn man. He was only a child when he was called up.’

‘He dug his own grave. He went down the well, put on a woman’s skirt and lay there. He couldn’t make a husband for Shukufa for six months. It’s no fun not to see sunlight for two years.’

‘It’s not good to speak of the dead, Ruhsara.’

‘Let the dead go to hell! He gained nothing for this life or the next. And, he got Tutu into trouble. Before mourning ends for one, it begins for the other. An inch of grass has grown on his grave, but the tragedy of his deeds has not finished – Shukufa’s health is too bad,’ said Saltanat and wiped her eyes.

‘It’s the time when the grass grows. If she can survive this spring, she will live till next spring,’ Ruhsara said, lowering her voice.

Sitting by her mother and washing mint, the schoolgirl suddenly thought of vast, dark green cornfields licked by the wind.