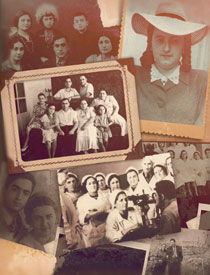

Heads of state and their close family are always in the public eye, but it’s difficult to see them as human behind all the publicity. Often, they become living legends, and the heroes of legends are stripped of human emotions. Zarifa Aliyeva has not been with us for 28 years now. And every year there are fewer people who knew her personally. What kind of person was she – the first First Lady?

Text: Yelena Averina

Design: Sergei Spurnik

I will be a doctor, like my father – this decision was perfectly natural for the young Zarifa. Aziz Mammadkarimovich Aliyev, head of the Azerbaijan Medical Institute, and later the peoples’ commissar of public health of Azerbaijan, was appointed in 1941 to the position of secretary of the Presidium of the Supreme Council of the Republic, but always remained a good physician.

During the war, there were many wounded soldiers in the Baku military hospital, set up in a university building. Zarifa and a girlfriend took charge of one of the wards. One day a badly wounded pilot was brought in. He had multiple fractures, serious burns and almost no skin left on his face. Worst of all, he was not fighting for life, but gazing indifferently at the ceiling, just waiting for the end. Young Zarifa, who could not imagine what it would be like to be thousands of kilometres away from home and to die alone without the support of loved ones, sat at his bed and tried to get him to talk. It took a few days before he began to say a little about himself.

It turned out that at the other end of the country the pilot had a wife and daughter who was the same age as Zarifa. The wounded man had not informed his family, he knew that at best he would be disabled, and at worst … The pilot was hoping for the worst-case scenario, as he did not want to be a burden on his loved ones. However, Zarifa persuaded him to dictate a letter to send home. As soon as the pilot finished, she ran to post the letter in the nearest post box, as if afraid he might change his mind. From then on, she not only looked after the patients, not shirking any dirty jobs, she also wrote letters at their dictation and posted them to their relatives. Who knows what was of most help to those patients – the injections and pills or the contact with home.

As well as their wounds, many patients were suffering from trachoma, a serious inflammation of the eye that can cause blindness. Zarifa’s observations of these patients became the basis of her candidate degree dissertation Treatment of trachoma with synthomycin in combination with other methods of therapy. It was to be published many years later, when Zarifa Azizovna, already a famous ophthalmologist, would become closely involved in tackling the problem of trachoma in the republic: in the 1950s, 60s and 70s, the populations of almost entire villages in Azerbaijan went blind.

After the end of the war, Zarifa graduated from the faculty for treatment and prophylaxis of the Azerbaijan Medical Institute, then worked for many years at the Department for Eye Diseases of the Azerbaijan State Institute of Advanced Medical Studies. Why was it so important for her to treat eye diseases? Probably, as a buoyant and cheerful person, she was oppressed by the thought that someone was deprived of the opportunity to see this world full of beauty. Zarifa Azizovna had her own working method. She was one of those rare doctors who treat patients equally well both in what they say and what they do. Few people could reassure patients as she did. Belief is half way to a successful recovery.

To see the light

While Zarifa studied and took her first steps in her profession, several important events took place in her life. In 1947, she went on holiday to Kislovodsk where she met a handsome young man, her compatriot Heydar Aliyev. As usually happens when two people from Baku meet, especially if they are of the same age, they turn out to have dozens of mutual acquaintances. That day, they just talked. But Heydar did not forget Zarifa and when the opportunity arose, he invited her out – now in Baku. Their courting time of flowers and chocolates proceeded slowly: it was perfectly normal at that time – something which has been forgotten in our day – for a young man to tenderly woo his girl for months and even years. However, Zarifa and Heydar were in no hurry to get married for another reason.

In the late 1940s, Heydar Aliyev was just a junior officer in the security department, but Zarifa was a daughter of the deputy chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Azerbaijan SSR. Soon, Aziz Aliyev was subjected to groundless accusations, poison-pen letters and discrediting evidence. Aziz Mammadkarimovich was demoted to the position of director of the Institute of Orthopaedics and Reconstructive Surgery and later he was dismissed from that position as well and sent to a village hospital as a mere doctor.

At this time, in contrast, Heydar was rising rapidly through the ranks. And now, it was not him who was no match for Zarifa, but her, the daughter of a disgraced party functionary, who might harm Heydar’s career. The minister of state security of Azerbaijan told him so directly, but Heydar replied firmly that he would not give up his beloved. This left a great impression on the minister who had not expected that reply. Finally, they left the couple alone. Heydar and Zarifa got married, formed a close circle of friends, had children and grandchildren. The main rule in the family was never to abandon one’s own, whatever the circumstances.

Eyes wide open

Member of the Presidium of the Scientific Society of Ophthalmologists of the Republic, member of the editorial board of the Ophthalmology Herald, member of the Azerbaijan Academy of Sciences, professor, deputy head of the Department of Eye Diseases of the Institute of Advanced Medical Studies, teacher, practising physician, author of 14 monographs and hundreds of scientific articles and, at the same time, First Lady, with a packed official life, plus wife, mother and grandmother… How did this fantastic woman manage all this?

When Aliyeva went to their summer house while they were still living in Baku, she did not relax there, but experimented on rabbits. She knew them all by name. Many of her works are devoted to tackling glaucoma and trachoma and many to medical ethics. Zarifa Aliyeva, a scientist with her own very individual style, showed the world the high quality of ophthalmology in Azerbaijan. She also made major scientific discoveries. For example, in the 1980s, her book The Fundamentals of Iridology was published in Baku, and her work Iridology was published in Moscow. This was the first scientific research in history written in this sphere: at that time few people believed that it was possible to judge the health of the whole organism by the iris.

She was a world pioneer in research into the pathologies of the eye in workers at enterprises that used iodine and processed rubber. She devised preventive measures for them. Zarifa Azizovna collected material for her scientific work in the most effective way – during ordinary surgery hours. At the Baku Air-Conditioning Plant, she had a scientific laboratory which she equipped herself. She also received patients at the Baku Superphosphates Plant and at the aluminium and petrochemicals plants in Sumqayit.

Zarifa Azizovna had her own room at the Baku Tyre Plant where she received patients every week. Workers came to her straight from their shifts – unwashed, in their dirty work clothes. She was approachable and polite to everyone. She involved colleagues in the difficult cases, helped complete strangers get into hospital and arranged for difficult treatment and operations. And, as usual, she persuaded patients that their disease would ease and found the important words of reassurance. She loved people very much, which is why she empathized with them so well.

She always supported her students and junior staff – the young ophthalmologists at the Institute of Advanced Medical Studies. They called her mother amongst themselves. However, although Zarifa Azizovna was a great scientist, the role of wife and mother was the most important in her life.

Wife and mother

One day, Heydar Aliyevich instructed me to accompany Zarifa Azizovna from Moscow to Baku, Aleksandr Ivanov, the head of the Aliyevs’ security since 1978, recalls.

We had tickets for an ordinary plane, but the plans changed at the last minute: it turned out that we would go on a special flight of Semyon Tsvigun, who was chairman of the KGB at that time. There were five of us in the cabin: Zarifa Azizovna, Tsvigun, his two guards and me. So, we took off but the plane did not gain height. One of Tsvigun’s guards went to find out what was happening and returned to the cabin white as a sheet. He said quietly that the pilots had shut themselves in the cockpit and there was no sense to be had from the air hostess as she was in hysterics.

As we found out later, the front chassis had been damaged at takeoff. We circled Vnukovo airport for about an hour, using up fuel, then tried to land. Of course, Zarifa Azizovna realized that something was wrong. She asked me what was happening. I tried to persuade her that everything was OK, but she could see from the window that the Kiev highway was blocked, and emergency cars and fire engines were assembling on the runway. It was on a Wednesday, publication day of Literaturnaya gazeta, which had a jokes column on the last page. I said: ‘Zarifa Azizovna, would you like to read page 16, you like it.’ She replied: ‘Sasha, this is no time for jokes!’ Of course, she was scared, but she behaved with dignity and said nothing about herself. All she said was, ‘How will my children live without me? How will my husband stand this?’

In 1982, Heydar Aliyevich was transferred to Moscow. Of course, Zarifa accompanied her husband there. Their daughter Sevil went with them. At that time, Ilham was already studying at MGIMO (Moscow State Institute of International Affairs). Soon his young wife, Mehriban, 18, also joined them. Her mother-in-law accepted her warmly, like a mother. Of course, Zarifa Azizovna missed Baku very much, but her husband and children were in Moscow, and her real home was where her family was.

She did not work as a doctor in Moscow, but she often met her colleagues in the capital and wrote and co-authored scientific works. Many luminaries of ophthalmology have left ecstatic recollections of her. Unfortunately, there is practically no-one left in this world who worked with Aliyeva. Alevtina Brovkina, a member of the Russian Academy of Medicine, doctor of medical sciences and Honoured Scientist of the Russian Federation, is a practising eye surgeon, who has fond memories of the years when she knew Zarifa Azizovna: Our scientific research did not intersect, but we knew each other personally. She was an amazing mother who brought up wonderful children. I have rarely seen mothers and daughters who are friends, but this is how it was in the Aliyev family.

She was an ideal mother – careful, understanding and loving. She was an ideal wife. She was a real woman. Every morning, Zarifa Azizovna saw her husband off to work. He left early and was the first of the members of the government to arrive in the Kremlin. Not a day went by that she did not follow the folk tradition of pouring a scoop of water after his car – in order to make his way smooth and easy. Every evening – Heydar Aliyevich came home very late, because he even watched the evening news programme Vremya at work – she met him at home, her hair brushed neatly, tastefully dressed, happy and not tired at all. Before his arrival, she would always refresh her make-up and neaten her hair.

Zarifa Azizovna was down-to-earth in her manner towards people: she was never arrogant or imperious, only kind and benevolent. After seeing her husband off to work, she would have breakfast, not in the dining room but in the room near the kitchen, where the cooks and waitresses ate. ‘So, girls,’ she would say, ‘let’s have a cup of tea.’ Over time, the ‘girls’ began seriously rivalry for the place of chief ‘tea confidante’, but the head of security, Alexander Ivanov, soon put a stop to these intrigues.

Zarifa Azizovna spread her warmth and openheartedness as generously as she gave many gifts. Whoever worked with the Aliyevs was always receiving presents from her, or maybe something tasty: a bottle of brandy, a box of fruit or pakhlava – for employees, their wives, children and parents. She never forgot anyone.

Alexander Ivanov remembers: When my wife was pregnant, Zarifa Azizovna always gave me packages of food. Once she gave me a fresh fish. I did not want to take it: ‘Thank you, but I don’t feel good taking this.’ Then she said: ‘It’s not for you, it’s for Ira. Do you know that if pregnant women eat fish, their children have blue eyes?’ Now, I often remind my son where his eye colour came from.

… Soon after moving to Moscow, Zarifa Aliyeva felt that she was seriously ill. She most probably understood what this disease was, but she did not tell anyone about it: she did not want to upset her family. Like that pilot. When it became impossible to hide the indisposition, she always said: There’s nothing to be concerned about: maybe it’s something I ate. It’s not dangerous, I am telling you this as a doctor.

Mikhail Chichin, the Aliyevs’ driver in Moscow, recalls: I took her for chemotherapy for three years. And all this time she forbade me to say anything about her disease to the children. She used various stories: sometimes she said that she was going to hospital for a check-up, or that she had problems with high blood pressure. At home, nobody knew anything about their mother’s disease until the end.

Of course, Heydar Aliyevich knew all about it. He involved the best oncologists, took her to foreign countries for treatment and found the best medicines. But, neither his love, nor the specialists’ experience could save his wife.

Aleksandr Ivanov, who witnessed those events, says that Heydar Aliyevich visited her in hospital every day. On Sundays, his only day off, he stayed there from morning till night. It was 10 days before Zarifa Azizovna’s death. I came in to her room before leaving the hospital. I bent down to kiss her on the cheek. She was very weak, I hardly heard when she asked me: ‘Sasha did you eat today?’ I said: ‘Yes, don’t think about it!’ Then we went home with Heydar Aliyevich. The cook met us and said, ‘Why did you tell Zarifa Azizovna that I left you hungry? How could I give you food, if you didn’t come home?’ It meant that after we left, she found the strength to call home and give the cook a scolding!

People with this disease change. They become irritable, capricious, whining, or withdraw into themselves. And they are very, very scared and it often becomes impossible for them to hide the horror. Zarifa Aliyeva saved her face and dignity up to the end; she remained loving, caring and calm. How did she keep herself together, this small, fragile woman, where did she get the strength? Of course, from the support of her loving family, although she had enough strength of mind herself. She died on 15 April 1985. And when two days later at her funeral Muslim Magomayev sang Sensiz – Without you – there was no man or woman at the Novodevichye cemetery who did not want to cry.

This is what always happens when a good person leaves this world.

This is a translation of an article that first appeared in the May-June 2013 issue of Baku magazine. It is printed here with the kind permission of the magazine.

Text: Yelena Averina

Design: Sergei Spurnik

I will be a doctor, like my father – this decision was perfectly natural for the young Zarifa. Aziz Mammadkarimovich Aliyev, head of the Azerbaijan Medical Institute, and later the peoples’ commissar of public health of Azerbaijan, was appointed in 1941 to the position of secretary of the Presidium of the Supreme Council of the Republic, but always remained a good physician.

During the war, there were many wounded soldiers in the Baku military hospital, set up in a university building. Zarifa and a girlfriend took charge of one of the wards. One day a badly wounded pilot was brought in. He had multiple fractures, serious burns and almost no skin left on his face. Worst of all, he was not fighting for life, but gazing indifferently at the ceiling, just waiting for the end. Young Zarifa, who could not imagine what it would be like to be thousands of kilometres away from home and to die alone without the support of loved ones, sat at his bed and tried to get him to talk. It took a few days before he began to say a little about himself.

It turned out that at the other end of the country the pilot had a wife and daughter who was the same age as Zarifa. The wounded man had not informed his family, he knew that at best he would be disabled, and at worst … The pilot was hoping for the worst-case scenario, as he did not want to be a burden on his loved ones. However, Zarifa persuaded him to dictate a letter to send home. As soon as the pilot finished, she ran to post the letter in the nearest post box, as if afraid he might change his mind. From then on, she not only looked after the patients, not shirking any dirty jobs, she also wrote letters at their dictation and posted them to their relatives. Who knows what was of most help to those patients – the injections and pills or the contact with home.

As well as their wounds, many patients were suffering from trachoma, a serious inflammation of the eye that can cause blindness. Zarifa’s observations of these patients became the basis of her candidate degree dissertation Treatment of trachoma with synthomycin in combination with other methods of therapy. It was to be published many years later, when Zarifa Azizovna, already a famous ophthalmologist, would become closely involved in tackling the problem of trachoma in the republic: in the 1950s, 60s and 70s, the populations of almost entire villages in Azerbaijan went blind.

After the end of the war, Zarifa graduated from the faculty for treatment and prophylaxis of the Azerbaijan Medical Institute, then worked for many years at the Department for Eye Diseases of the Azerbaijan State Institute of Advanced Medical Studies. Why was it so important for her to treat eye diseases? Probably, as a buoyant and cheerful person, she was oppressed by the thought that someone was deprived of the opportunity to see this world full of beauty. Zarifa Azizovna had her own working method. She was one of those rare doctors who treat patients equally well both in what they say and what they do. Few people could reassure patients as she did. Belief is half way to a successful recovery.

To see the light

While Zarifa studied and took her first steps in her profession, several important events took place in her life. In 1947, she went on holiday to Kislovodsk where she met a handsome young man, her compatriot Heydar Aliyev. As usually happens when two people from Baku meet, especially if they are of the same age, they turn out to have dozens of mutual acquaintances. That day, they just talked. But Heydar did not forget Zarifa and when the opportunity arose, he invited her out – now in Baku. Their courting time of flowers and chocolates proceeded slowly: it was perfectly normal at that time – something which has been forgotten in our day – for a young man to tenderly woo his girl for months and even years. However, Zarifa and Heydar were in no hurry to get married for another reason.

In the late 1940s, Heydar Aliyev was just a junior officer in the security department, but Zarifa was a daughter of the deputy chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Azerbaijan SSR. Soon, Aziz Aliyev was subjected to groundless accusations, poison-pen letters and discrediting evidence. Aziz Mammadkarimovich was demoted to the position of director of the Institute of Orthopaedics and Reconstructive Surgery and later he was dismissed from that position as well and sent to a village hospital as a mere doctor.

At this time, in contrast, Heydar was rising rapidly through the ranks. And now, it was not him who was no match for Zarifa, but her, the daughter of a disgraced party functionary, who might harm Heydar’s career. The minister of state security of Azerbaijan told him so directly, but Heydar replied firmly that he would not give up his beloved. This left a great impression on the minister who had not expected that reply. Finally, they left the couple alone. Heydar and Zarifa got married, formed a close circle of friends, had children and grandchildren. The main rule in the family was never to abandon one’s own, whatever the circumstances.

Eyes wide open

Member of the Presidium of the Scientific Society of Ophthalmologists of the Republic, member of the editorial board of the Ophthalmology Herald, member of the Azerbaijan Academy of Sciences, professor, deputy head of the Department of Eye Diseases of the Institute of Advanced Medical Studies, teacher, practising physician, author of 14 monographs and hundreds of scientific articles and, at the same time, First Lady, with a packed official life, plus wife, mother and grandmother… How did this fantastic woman manage all this?

When Aliyeva went to their summer house while they were still living in Baku, she did not relax there, but experimented on rabbits. She knew them all by name. Many of her works are devoted to tackling glaucoma and trachoma and many to medical ethics. Zarifa Aliyeva, a scientist with her own very individual style, showed the world the high quality of ophthalmology in Azerbaijan. She also made major scientific discoveries. For example, in the 1980s, her book The Fundamentals of Iridology was published in Baku, and her work Iridology was published in Moscow. This was the first scientific research in history written in this sphere: at that time few people believed that it was possible to judge the health of the whole organism by the iris.

She was a world pioneer in research into the pathologies of the eye in workers at enterprises that used iodine and processed rubber. She devised preventive measures for them. Zarifa Azizovna collected material for her scientific work in the most effective way – during ordinary surgery hours. At the Baku Air-Conditioning Plant, she had a scientific laboratory which she equipped herself. She also received patients at the Baku Superphosphates Plant and at the aluminium and petrochemicals plants in Sumqayit.

Zarifa Azizovna had her own room at the Baku Tyre Plant where she received patients every week. Workers came to her straight from their shifts – unwashed, in their dirty work clothes. She was approachable and polite to everyone. She involved colleagues in the difficult cases, helped complete strangers get into hospital and arranged for difficult treatment and operations. And, as usual, she persuaded patients that their disease would ease and found the important words of reassurance. She loved people very much, which is why she empathized with them so well.

She always supported her students and junior staff – the young ophthalmologists at the Institute of Advanced Medical Studies. They called her mother amongst themselves. However, although Zarifa Azizovna was a great scientist, the role of wife and mother was the most important in her life.

Wife and mother

One day, Heydar Aliyevich instructed me to accompany Zarifa Azizovna from Moscow to Baku, Aleksandr Ivanov, the head of the Aliyevs’ security since 1978, recalls.

We had tickets for an ordinary plane, but the plans changed at the last minute: it turned out that we would go on a special flight of Semyon Tsvigun, who was chairman of the KGB at that time. There were five of us in the cabin: Zarifa Azizovna, Tsvigun, his two guards and me. So, we took off but the plane did not gain height. One of Tsvigun’s guards went to find out what was happening and returned to the cabin white as a sheet. He said quietly that the pilots had shut themselves in the cockpit and there was no sense to be had from the air hostess as she was in hysterics.

As we found out later, the front chassis had been damaged at takeoff. We circled Vnukovo airport for about an hour, using up fuel, then tried to land. Of course, Zarifa Azizovna realized that something was wrong. She asked me what was happening. I tried to persuade her that everything was OK, but she could see from the window that the Kiev highway was blocked, and emergency cars and fire engines were assembling on the runway. It was on a Wednesday, publication day of Literaturnaya gazeta, which had a jokes column on the last page. I said: ‘Zarifa Azizovna, would you like to read page 16, you like it.’ She replied: ‘Sasha, this is no time for jokes!’ Of course, she was scared, but she behaved with dignity and said nothing about herself. All she said was, ‘How will my children live without me? How will my husband stand this?’

In 1982, Heydar Aliyevich was transferred to Moscow. Of course, Zarifa accompanied her husband there. Their daughter Sevil went with them. At that time, Ilham was already studying at MGIMO (Moscow State Institute of International Affairs). Soon his young wife, Mehriban, 18, also joined them. Her mother-in-law accepted her warmly, like a mother. Of course, Zarifa Azizovna missed Baku very much, but her husband and children were in Moscow, and her real home was where her family was.

She did not work as a doctor in Moscow, but she often met her colleagues in the capital and wrote and co-authored scientific works. Many luminaries of ophthalmology have left ecstatic recollections of her. Unfortunately, there is practically no-one left in this world who worked with Aliyeva. Alevtina Brovkina, a member of the Russian Academy of Medicine, doctor of medical sciences and Honoured Scientist of the Russian Federation, is a practising eye surgeon, who has fond memories of the years when she knew Zarifa Azizovna: Our scientific research did not intersect, but we knew each other personally. She was an amazing mother who brought up wonderful children. I have rarely seen mothers and daughters who are friends, but this is how it was in the Aliyev family.

She was an ideal mother – careful, understanding and loving. She was an ideal wife. She was a real woman. Every morning, Zarifa Azizovna saw her husband off to work. He left early and was the first of the members of the government to arrive in the Kremlin. Not a day went by that she did not follow the folk tradition of pouring a scoop of water after his car – in order to make his way smooth and easy. Every evening – Heydar Aliyevich came home very late, because he even watched the evening news programme Vremya at work – she met him at home, her hair brushed neatly, tastefully dressed, happy and not tired at all. Before his arrival, she would always refresh her make-up and neaten her hair.

Zarifa Azizovna was down-to-earth in her manner towards people: she was never arrogant or imperious, only kind and benevolent. After seeing her husband off to work, she would have breakfast, not in the dining room but in the room near the kitchen, where the cooks and waitresses ate. ‘So, girls,’ she would say, ‘let’s have a cup of tea.’ Over time, the ‘girls’ began seriously rivalry for the place of chief ‘tea confidante’, but the head of security, Alexander Ivanov, soon put a stop to these intrigues.

Zarifa Azizovna spread her warmth and openheartedness as generously as she gave many gifts. Whoever worked with the Aliyevs was always receiving presents from her, or maybe something tasty: a bottle of brandy, a box of fruit or pakhlava – for employees, their wives, children and parents. She never forgot anyone.

Alexander Ivanov remembers: When my wife was pregnant, Zarifa Azizovna always gave me packages of food. Once she gave me a fresh fish. I did not want to take it: ‘Thank you, but I don’t feel good taking this.’ Then she said: ‘It’s not for you, it’s for Ira. Do you know that if pregnant women eat fish, their children have blue eyes?’ Now, I often remind my son where his eye colour came from.

… Soon after moving to Moscow, Zarifa Aliyeva felt that she was seriously ill. She most probably understood what this disease was, but she did not tell anyone about it: she did not want to upset her family. Like that pilot. When it became impossible to hide the indisposition, she always said: There’s nothing to be concerned about: maybe it’s something I ate. It’s not dangerous, I am telling you this as a doctor.

Mikhail Chichin, the Aliyevs’ driver in Moscow, recalls: I took her for chemotherapy for three years. And all this time she forbade me to say anything about her disease to the children. She used various stories: sometimes she said that she was going to hospital for a check-up, or that she had problems with high blood pressure. At home, nobody knew anything about their mother’s disease until the end.

Of course, Heydar Aliyevich knew all about it. He involved the best oncologists, took her to foreign countries for treatment and found the best medicines. But, neither his love, nor the specialists’ experience could save his wife.

Aleksandr Ivanov, who witnessed those events, says that Heydar Aliyevich visited her in hospital every day. On Sundays, his only day off, he stayed there from morning till night. It was 10 days before Zarifa Azizovna’s death. I came in to her room before leaving the hospital. I bent down to kiss her on the cheek. She was very weak, I hardly heard when she asked me: ‘Sasha did you eat today?’ I said: ‘Yes, don’t think about it!’ Then we went home with Heydar Aliyevich. The cook met us and said, ‘Why did you tell Zarifa Azizovna that I left you hungry? How could I give you food, if you didn’t come home?’ It meant that after we left, she found the strength to call home and give the cook a scolding!

People with this disease change. They become irritable, capricious, whining, or withdraw into themselves. And they are very, very scared and it often becomes impossible for them to hide the horror. Zarifa Aliyeva saved her face and dignity up to the end; she remained loving, caring and calm. How did she keep herself together, this small, fragile woman, where did she get the strength? Of course, from the support of her loving family, although she had enough strength of mind herself. She died on 15 April 1985. And when two days later at her funeral Muslim Magomayev sang Sensiz – Without you – there was no man or woman at the Novodevichye cemetery who did not want to cry.

This is what always happens when a good person leaves this world.

This is a translation of an article that first appeared in the May-June 2013 issue of Baku magazine. It is printed here with the kind permission of the magazine.