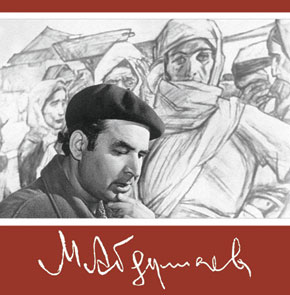

One of the best known artists of 20th century Azerbaijan, Mikayil Abdullayev painted portraits, pastoral landscapes and industrial scenes. He created mosaics that are seen every day by thousands of travellers as they pass through Baku’s Nizami metro station and worked on stage design, including for a special concert at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow. Art critic Mohbaddin Samad looks at the life and work of this versatile artist.

Mikayil Abdullayev was born in 1921 in Baku into the family of a stocking manufacturer. His first ambition as a child was to be an actor. He later chose art although he suddenly lost his vision for a while and was unable to paint. When he recovered his sight, he started to draw in coal and chalk on the outside walls of the family home which soon attracted attention.

Mikayil Abdullayev said that his first artistic impressions came from the illustrations of Azim Azimzadeh in Mirza Alakbar Sabir’s Hophopnameh, a book that was owned by practically every family in Azerbaijan at that time. The contrasting scenery of the Absheron peninsula was another source of inspiration for the budding artist. When he relaxed at summer houses in Absheron he would make sketches at various times of day. His impressions of Absheron can be seen in his work: contrasting shades in a narrow street lit by the eastern sun; dark green fig trees against a backdrop of blue sky and shimmering sand; flat-roofed yellow-grey houses, sometimes flushed with orange; and groups of brightly clad villagers out for a Sunday stroll.

Impressionism

Mikayil finished the 7th form of school in 1935 and entered the State Art School of Azerbaijan. This was a time of struggle between Formalism and Realism in art, which was reflected in teachers and students at the school too. He deeply loved the work of Rembrandt, Courbet and Monet, so experimented in the Impressionist style. At the same time, he always appreciated Classical and Realist work too.

Mikayil Abdullayev realised as a student that success in art could be achieved only through hard work, which he made his byword in life.

The young artist’s sketches and landscapes were shown in exhibitions organized by the Union of Artists. Art critics and art lovers saw something of Russian Impressionist Korovin or Realist portrait painter Sorin in his work. In 1939, when he was 17, Abdullayev and his classmates began to tackle more complex compositions such as Interval at the Opera House and Family of a Collective Farm Member.

He passed the entrance exams for the Surikov Art Institute in Moscow and began his studies there in 1939. At that time, well-known Russian artists Sergey Gerasimov, Grigory Shegal, Alexander Osmyorkin, Peter Pokarzhevsky and others taught there. Abdullayev was mainly taught by People’s Artist Sergey Gerasimov and he learnt a great deal in his studio.

The struggle between Realism and Formalism was being waged at the Surikov Institute too. After his first encounters with Sergey Gerasimov, Mikayil Abdullayev felt that his teacher did not like his style, copied from Manet and the Impressionists. He said later:

I have to admit that I painted under the influence of this artist’s work both in art school and at the Institute. Even more, I learnt by heart almost everything written about him in Russian during the past century because I liked him so much. I knew all the albums of his work published in foreign languages. Some colleagues of mine also came under his influence. Our Abdulkhaliq, who was in the year below me, liked Manet very much. When one of his teachers introduced him, “Student Abdulkhaliq”, Sergey Vasilyevich replied: “I can see Abdul and Manet beside him.” For a long time we called Abdulkhaliq “Abdul Manet” amongst ourselves.

Sergey Gerasimov saw me through the same lens as Abdulkhaliq. The chairman of the student commission once told me that the “Manet matter” had caused a lot of trouble. Members of the commission were going to give you a “5” [top marks] for painting but Sergey Gerasimov did not agree at all. He said that they were the work of a student who was pretending to be a great artist too soon. Eventually, he said, “Well, give him 5 for painting, but don’t forget this Manet is the worst.” After this I really thought things through. I decided that Sergey Vasilyevich was fair in his criticism of me and Abdulkhaliq. He wanted to see in us painters from Azerbaijan. Copying Manet was not the right way.

Move towards Realism

For all the paradoxes and criticism, Mikayil Abdullayev could not immediately escape the influence of Manet and still painted a lot in an Impressionist style.

Mikayil’s education was interrupted when the Soviet Union joined the Second World War in 1941. He returned to Baku and with other artists created posters and placards for the Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union (TASS), including excellent portraits of heroic fighters. This period led Mikayil Abdullayev further in the direction of Realist painting. The results can be seen in the work Evening, shown at the USSR-wide art exhibition in 1947 in Moscow.

Evening conveys the emotion and optimism of the Karabakh girls who are its subject. Although it is the work of a young artist, it is one of Azerbaijan’s finest pictures in terms of composition, skill, harmony and balance of colour. His painting Joy (Sevinj) is similar. Both his teacher, Sergey Gerasimov, and the director of the Surikov Institute, Academician Igor Grabar, appreciated the work. Grabar said of Joy: The picture is enormously full of colour and light… This is truly an inspiring hymn to love of life and endless happiness.

The painting won a silver medal and Art Institute diploma.

Abdullayev returned to the Surikov Institute in Moscow after the end of the war. During his studies he created a series of portraits of eminent figures from Azerbaijan’s literary and art scene. The portraits of composer Uzeyir Hajibeyov, poet Samad Vurgun, writer Mirza Ibrahimov, actress Marziyya Davudova and singer Shovkat Mammadova deserve special attention for their revelation of their subjects’ inner worlds.

Mingachevir

One of the country’s major post-war construction projects was the hydro-electric power station in Mingachevir in western Azerbaijan. Abdullayev, who was in his final year at the Surikov Institute, was fascinated by the project. When he came to Baku for the winter and summer holidays, he would travel to Mingachevir to sketch the work in progress. These sketches and notes were the basis for his Mingachevir Series of paintings. The series consists of Lights of Mingachevir, On the Road of the Five-Year Plan, Builders of Happiness, Girlfriends and On the Banks of the Kura River. The industrial landscape of the Lights of Mingachevir deserves particular attention for its composition and use of colour to depict faith in human strength and the poetry of construction. The picture went down well at the all-USSR exhibition in Moscow and later in the exhibition of the Second International Festival of Youth in Budapest.

Mingachevir was a recurring theme in the young artist’s work. After graduating from the Surikov Art Institute in 1949, he devoted more work to Mingachevir. The industrial landscape Builders of Happiness is one of the artist’s best in this genre. The subject is clear and simple – two young builders, a man and woman, are shown having a conversation during their lunch break, in effect a date. The psychological nuances of the date are conveyed through colour. The painting is testament to the artist’s understanding of life and human nature and his excellent observation skills. This lyrical work creates harmony between public and private aims and desires and is a reflection on happiness.

The painting inspired both Soviet and foreign artists. Prominent East German painter Walter Womacka said he was influenced by Builders of Happiness when he painted his popular On the Beach in 1962.

The Mingachevir Series in many ways defined the future development of industrial landscape painting in Azerbaijan.

Masalli Suite

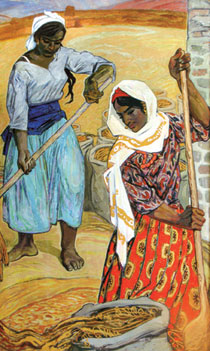

As a young painter Mikayil Abdullayev was always looking for new topics, methods of expression and shades of colour. He used lyrical, bright colours when painting motifs from daily life. This can be seen in many of his works that also reflect the spirit of the 1950s, with its atmosphere of patriotic pathos: On the Way to the Five-Year Plan, In the East, Girlfriends, Girls from Masalli, Tea Picking in Astara, Woman Farmer from Lenkeran, Morning in 1941, Girls from Khachmaz, In Absheron, Girls Hulling Rice, Cotton, Vine Growers, In the Cornfield, On the Steppes of Azerbaijan and The Youth of Mothers.

Most of these paintings formed the basis of his next series which he called Masalli Suite. While the Mingachevir Series drew attention to Mikayil Abdullayev, the Masalli Suite really made his name. Critics saw the Masalli period as a turning point in the artist’s work. For a long time he had been experimenting in his studio with still lifes, trying to get rich, sharp, bright colours, but had not been able to achieve it. The first time he managed it was in the Masalli paintings. This can be seen clearly in the dark landscape in works such as the Road to Masalli, moreover a contrast to the artist’s usual preference for bright colours. Most of the works in this series are rounded and reflect real life through the use of vibrant colour. That’s why they became a model for Azerbaijani artists.

The Azerbaijani people have always liked fine, bright colours. We can see this in the thrilling use of colour in carpets, ceramics and the miniatures of the Tabriz school. That’s why Mikayil Abdullayev always turned to Azerbaijani applied arts and national traditions for inspiration.

Artists from the Tabriz school of the 15th and 16th centuries, such as Soltan Muhammad and Behzad Aga Mirek, used warm, bright colours and preserved proportionality in their miniatures. Mikayil Abdullayev also followed this path. Warm, bright colours dominate his works and please the eye. Although the compositions Collective Farm Market in Masalli, Following a Child, Little Shepherd and Joy, as well as the monumental Girls from Masalli, Tea Picking in Astara, Woman Farmer from Lenkeran, Morning of 1941, Girls Hulling Rice, On the Steppes of Azerbaijan and The Youth of Mothers, depict both joyful and sad moments, their warm, bright colours inspire a sense of confidence in the future. These were the features that led to the picture Joy, included in the Masalli Suite, receiving a diploma and silver medal from the Art Institute and a high commendation at the World Exhibition in Brussels in 1958. In Joy critics appreciated the poetry of composition and depiction of eternal harmony and rhythm between feminine beauty and the beauty of nature. The beauty of woman and nature are so intermingled through many shades of colour that it is impossible to imagine them being separate.

Illustrator

Abdullayev was a very versatile artist and earned renown in Azerbaijan as an illustrator as well as a painter.

The series of graphic works On the Other Side of the Araz River, created in the 1950s, conveys images of Southern Azerbaijan, the part of Azerbaijan that lies in Iran. The first picture in the series is At Every Turn and the last Hope. The artist’s illustrations for the novel Future Day by Mirza Ibrahimov are very similar to the Araz series.

Abdullayev’s multi-plot miniature illustrations for the epic Book of Dada Qorqud are valuable pieces of art in their own right as well as informative illustrations. Through the miniatures the artist conveys the wisdom of Qorqud, the heroism of Bugaj, son of Dirsa khan, and of Qaraja the Shepherd, and the beauty of Banu Chichak.

The artist’s illustrations for Nizami Ganjavi’s Khamsa, Fizuli’s Leyli and Majnun and Bakhtiyar Vahabzade’s Shabi-Hicran injected freshness into the traditions of miniatures.

Theatre designer

Mikayil Abdullayev also applied his deep knowledge of the decorative arts of Azerbaijan to stage design. He designed original sets for many plays performed in Baku. It was Abdullayev who designed the stage for the final concert in a 10-day festival of the literature and art of Azerbaijan in 1959 at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow. In his sets for Uzeyir Hajibeyli’s opera Leyli and Majnun, the artist used the traditions of Azerbaijani miniatures for the same expressive effect as the composer used Azerbaijani mugham. His sets for Hajibeyov’s opera Koroghlu and the ballets Chitra by Niyazi and Path of Thunder by Qara Qarayev also achieved a harmony of music and colour.

Italy, India

From the 1950s, Mikayil Abdullayev’s fame spread beyond Azerbaijan across the Soviet Union and later worldwide. He had personal exhibitions in many countries. At the same time, the artist also travelled to find inspiration for his work. He returned from trips to Italy, India, Afghanistan, Hungary and Poland between 1956 and 1971 full of impressions and with a vast number of sketches and drafts. His gouache paintings Through the Eyes of Baku from a trip to Italy were exhibited to considerable acclaim in Baku in 1957 and in Moscow in 1962 at the 6th Exhibition of Members of the Art Academy of the USSR. His books Memories of Italy and Through the Eyes of Baku, published in Azerbaijani and Russian, are the fruit of that trip.

One of Mikayil Abdullayev’s most cherished desires was to visit India, the land of legend. His tour of India, like his earlier trip to Italy, had a great effect on his work. He visited Delhi, Calcutta, Agra, Jaipur and dozens of other cities and regions during a three-month trip, bringing back more than 100 sketches. These sketches and drafts were the basis of some fantastic, colourful paintings.

He found similarities in India with the spirit of Azerbaijan, and these are reflected in his series Indian Symphony. Paintings from this series were awarded the Jawaharlal Nehru Prize in 1970 and were exhibited in Baku, Moscow and European and Eastern countries.

The artist’s trips to Afghanistan, Poland and Germany were also very productive. His work reflected the social and cultural lives of ordinary people in these countries, their history and ethnography.

Mosaics

Abdullayev was a very versatile artist. Another area where he enjoyed success was mural painting. His first major works of note in this field are the mosaics based on the poems of Nizami which he created between 1973 and 1979 for the underground hall of Baku’s Nizami metro station.

However, he did not find it easy to design the mosaics. Although he had already illustrated Nizami’s epic Khamsa, the artist was nervous about conveying this philosophy successfully in the limited space of the mosaic panels. He re-read Khamsa and selected the best scenes from the five epic poems to place in the recessed alcoves of the underground hall. However, there was a problem – the original architect’s design included a bust of Nizami, but not the mosaic panels. Architect Mikayil Useynov (whose work was featured in the July edition of Visions) was persuaded to incorporate 18 mosaics in nine alcoves facing each other.

The artist took into consideration the correspondence of shape and content in the motifs of Khamsa as he created the mosaics. From The Treasury of Mysteries the mosaics depict scenes from the Conversation of Owls, Story of the Brick Maker and Sultan Sanjar and the Old Woman; from Khosrov and Shirin they show scenes Khosrov and Shirin, Farhad at Bisutun and Farhad and Shirin; from Leyli and Majnun they depict Majnun and his Father, Leyli and Majnun and At Leyli’s Grave; from the Seven Beauties they show The Tragedy of Simnar, Bahram and the Dragon, The Courage of Bahram and Fitna and from the Sharafnameh (On Honour) and Iqbalnameh (On Fate), they depict scenes of Iskander (Alexander the Great) and the Shepherd, Seven Scholars, Nushaba and Iskander, Death of Darah and Mani the Carver.

The paints used for mosaics need to achieve a balance – they should be neither too “loud” nor too reserved. Mikayil Abdullayev took a delicate approach to this and used softer colours to take account of the seven-and-a-half metre distance between the two rows of mosaics. He also made good use of monochrome colours alongside the richly coloured scenes. In 1979 Mikayil Abdullayev completed work on the 18 mosaic panels and the metro station with its mosaics opened to popular acclaim.

Around the same period, in 1973, Mikayil Abdullayev worked with sculptor Albert Mustafayev on the statue of Nasimi. The statue, which stands near the junction of Nizami and Samad Vurghun streets in Baku, also became a public favourite.

While researching the artist’s heritage, we found many fine Impessionist-style paintings in his studio. Surprisingly perhaps, these works have not been included in catalogues or albums or appeared in exhibitions. The time has come to display them to art lovers and increase even further Mikayil Abdullayev’s popularity.

The artist died in 2002 at the age of 80. He had been awarded the titles People’s Artist of the USSR and of the Republic of Azerbaijan, won the state prize of the Republic of Azerbaijan and Jawaharlal Nehru Prize and was a full member of the USSR Academy of Art.

Having lived through the turbulence of the 20th century in Azerbaijan, Mikayil Abdullayev left a colourful visual record of the country’s culture, way of life and landscape.

About the author: Mohbaddin Samad is the author of many publications and film-scripts on art, especially Azerbaijani art.