Foreign companies and entrepreneurs rushed to the Caucasus in the late 19th century, a result of tsarist Russia’s attempts to modernize and industrialize the whole empire. The enterprises did not necessarily intend to exploit natural resources, but when they saw the promising, unexplored opportunities, resource extraction was the obvious way to go. One such enterprise was Siemens & Halske AG, founded in Germany in 1847 by Werner von Siemens and Johann Georg Halske.

The Siemens brothers came across the copper mine in Gedabey at almost the same time as the Nobel brothers got involved in the oil industry in Baku. Siemens & Halske AG had won a contract to build and maintain the telegraph lines in Russia, including the Caucasus, in the 1850s and 60s. During this period, Walter von Siemens spotted the lucrative business opportunity in Gedabey and convinced his older brothers, Carl and Werner, to invest in it.

The acquisition of the mine by the Siemens brothers met with strong disapproval from their partner, Johann Halske, which contributed to his break from Siemens & Halske AG. This was partly because the company’s core industrial focus was not mining, but telegraphic services, communications and electric power generation. The brothers never merged the mining business into their main company, but ran the mine as a private business of the Siemens brothers – Werner, Carl and Walter.

Mining develops

Werner von Siemens described the mine in Gedabey, or Kedabeg as he called it, upon his first visit in 1865:

The copper mine of Kedabeg is very old: it is even asserted that it is one of the oldest mines from which copper was actually extracted in pre-historic times… At any rate the number of old works, which crown the summit of the metalliferous mountain, testifies to the antiquity of the working of the mine as does the occurrence of native copper, and finally the circumstance that extensive pre-historic burial-grounds exist in the vicinity of Kedabeg.

The purpose of Werner’s visit to Gedabey was to give a final decision on Walter’s proposal to purchase the mine. It was operated by Greeks, although some shares had already been bought in 1864. At that time, Walter was based permanently in the Tbilisi office of Siemens & Halske’s Russian subsidiary in order to manage contractual obligations to maintain and repair imperial Russia’s telegraph lines in the Caucasus. The Russian subsidiary had its headquarters in the capital, St Petersburg, and was directed by Carl von Siemens.

The complete purchase of the Gedabey mine in 1865 was a timely decision for two short-term reasons: the first was that the company’s contract for “Construction and Maintenance of the Imperial Russian Telegraph Lines” was due to expire in 1867 and no further services had been requested by the government; the second was related to a grand project called the Indo-European Telegraph Line which was to run from London to Calcutta through four states, Great Britain, Prussia, Russia (via the Caucasus, crossing the Russian-Persian border in Julfa) and Persia and would required considerable amounts of copper.

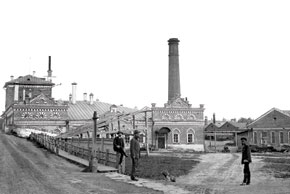

The mine was operated by primitive methods when the Siemens brothers took over from the Greeks. Shortly after the transaction, in 1865 they built a copper smelter and in 1873 connected it to the mine by a 6-km narrow gauge railway. The mining operations were managed by Walter who was supported by a team composed of mainly German and Russian engineers from the Baltic provinces.

In 1868, Walter’s untimely death in an accident led to a volatile management situation. After Walter’s death, Carl took over remote management of operations in Gedabey, but moved from St Petersburg to London after his wife’s death in 1869. The younger Siemens brother, Otto, then took over management. However, Otto had tuberculosis and his poor health suffered from the climate in Gedabey.

Despite the management difficulties, the copper mine in Gedabey was crucial in supplying a substantial amount of copper wire for the Indo-European Telegraph line, which was built in 1867-70 and operated until 1931.

When company chairman Werner von Siemens visited Gedabey for the second time in 1868, the mine’s future hung in the balance, despite rising copper production and revenues. When Otto died in 1871, the director of the mine, Carl Schnabel, ran it down through poor management.

Profitability improved with the appointment in 1877 of Carl Schnabel’s successor, Gustav Kölle, who ran the mine until 1905. Kölle proved to be very successful in sustaining profitability, while triggering a new stage in development. Mining was extended to Qalakend, where a new copper smelter was built in 1883 with a production capacity of 25,000 poods/450 tons per year.

Innovations

The first, 28-km railway between Gedabey and Qalakend was built in 1879-83, before the Baku-Batumi railway. The railway was a masterpiece of engineering to tackle the complexity of the route – it included multi-arched viaducts over mountain rivers and sections cut through hard mountain rock.

The railway was also used to transport combustible materials, since the smelters required a steady supply of fuel. As smelting operations became more sophisticated, fuel was in greater demand. This prompted the decision to convert the smelters from wood and coal to petroleum-based products such as masut and naphtha. The location of Gedabey with its harsh winters and high rainfall made it impossible to transport petroleum products from the railway station in Shamkir up to the mountains all year round. To overcome this challenge, the Siemens brothers built a pipeline to pump petroleum from Dallar station near Shamkir up to the smelters in 1892. Two years later the pipeline was extended to Gedabey.

Werner later designed a new method of electrolytic refining of minerals by electric current. The electric current was generated by dynamos with the help of large turbines of thousands of horse-power which had been installed in the Shamkir River valley in Qalakend. This was the first hydroelectric power plant in imperial Russia and also provided modern electric light.

Copper was the main product of the Gedabey Copper Plant. The purity of refined copper bullion averaged at 99.9%, while gold and silver minerals were considered secondary output and were shipped to Germany without being fully processed. Furthermore, the gold metal content was very low, at 1/15 to 1/17 of leached ore. The records for 1867-1914 show that 58 000 t of copper, more than 3 t of gold and 12 t of silver were produced. Gedabey accounted for 20% of all copper production in the Russian Empire at that time.

Following the declaration of war with Germany in 1914, Tsar Nicholas II decreed a freeze on all the assets of, and contracts with, citizens of Germany. Before the decree, the Siemens brothers had been able to register the Gedabey Copper Plant under the umbrella ownership of Russian citizens Maria Karlovna Grevenits (von Graevenitz) and Sharlotta Karlovna Buksgevden (Buxhoeveden). It was the Soviets’ nationalization of the assets in 1920 that brought an end to the era of the Siemens brothers in Gedabey.

Urbanization: from cave dwellings to stone houses

The mine required a permanent labour force, as the mining industry works around the clock. A characteristic of the people of Gedabey was that they were nomadic and would disappear all of a sudden when they had earned enough money to buy weapons and a horse. The Siemens brothers resolved this issue with the capitalist notion of creating needs that had to be paid for. And in this women played a special role. As Werner put it: The handle was afforded by the natural inclination of the female sex for a pleasant family-life and their easily awakened vanity and love of dress.

The local people at the time lived in the caves, or underground dwellings, common in the eastern Caucasus. As part of the plan to settle the workers, stone houses were built for a few workmen, complete with modern facilities. The houses went down well with both the workmen and their wives and were coveted by those still living in caves. Local people rushed to live in European-style stone and brick houses, and in so doing created a permanent labour force.

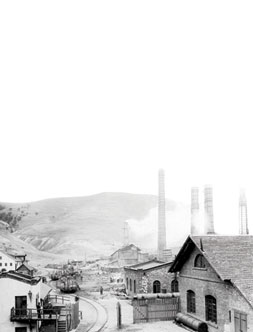

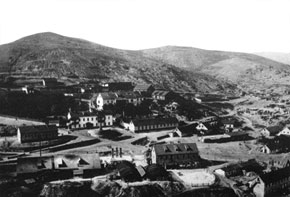

Moreover, a number of brickworks had already been built in the area to provide bricks for mine infrastructure as well as housing. By the end of the 19th century, the construction work had changed the face of Gedabey. Werner Siemens described his impressions when he paid his third visit to the town in 1890 after a gap of 25 years: It is the thoroughly European spectacle of a small, picturesquely situated, manufacturing town, which presents itself to view with huge furnaces and large buildings, among them a Christian chapel, a school and inn fitted up in European fashion.

This was no longer simply a mine and smelter but a thriving town. Besides the management and engineering buildings and workers’ houses, there was a well-equipped hospital, which served local people as well as miners. A House of Culture was the main venue for cultural and social events, including plays and dances, and had a library. As is the case with other German settlements in Azerbaijan, the Siemens brothers built a German Lutheran church in Gedabey. However, the church no longer exists. Two Russo-German schools were also founded: one in Gedabey and the other in Qalakend. These schools were very important in terms of producing skilled personnel for the mine.

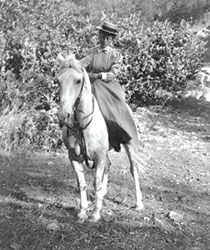

Mine employees were involved in various sports in their free time, including skating and horse-riding. The Shamkir River valley was outstandingly beautiful and an ideal place to enjoy outdoor activities. The Germans dubbed it “biblical paradise”. One of the pictures of the time depicts Antonie and Bertha Siemens, the wives of Werner and Carl respectively, enjoying a sightseeing tour of Qalakend, the area they called “paradise”. Ice-skating was organized when the Shamkir River froze over in Qalakend during the winter months. Werner writes in his memoirs of a bear hunt in the forest, which was common practice for other mine employees too. Thanks to this hunting tradition, there are no more bears to be found in the forests of Gedabey.

Waldemar Belck’s archaeological surveys around Qalakend in the late 19th century revealed many late Bronze Age settlements and burial grounds which gave an understanding of the way of life thousands of years ago. Belck is reported to have surveyed more than 300 burial grounds. All his finds were taken to Germany and are held in museums in Munich and Berlin. His surveys are covered comprehensively in a publication called Kalakent: Früheisenzeitliche Grabfunde aus dem transkaukasischen Gebiet von Kirovabad, Jelisavetopol by Wolfram Nagel and Eva Strommenger. Unfortunately, the book is available only in German, and has been translated into neither Azerbaijani nor English.

Forgotten heritage

Almost all the surviving infrastructure built in Gedabey in the 19th century, including the school, hospital and workers’ hostels, has been privatized and the purpose of many of the buildings has changed. Most of them are either private residential property or offices of the local authorities. For instance, the mine’s administrative building now houses the Gedabey Agricultural Seed Office but is closed most of the time. Fortunately, the Culture House still preserves part of its original purpose and today is the only library in Gedabey.

The surviving smelter infrastructure lies mainly to the south and south-west of Gedabey town centre. Modern urbanization has hidden the 19th century smelter works like snow covers the ground. However, the surviving buildings of the Siemens era are instantly recognisable for their architecture. They include the Russo-German school, hospital, administrative building, railway arches and a workers’ hostel. One of the brickworks is still standing, though half in ruins, close to the old mine. Most of the buildings used red brick produced at those brickworks.

It is no wonder that people call the hill and downstream area, where the old Gedabey mine is located, Copper Hill (Mis daghi) and Copper River (Mis chayi) respectively. The current location of the gold and copper deposit that modern-day company Anglo-Asian Mining is exploiting is exactly the same hill where the old Gedabey Mine was. Three adits, or horizontal entries into the mine workings, remain but are filled-in with debris or water. The narrow gauge-line also remains and 19th century slag can be found on the eastern slope of Copper Hill, where there is also an old barracks at the bottom of the slope.

Smelter work leaves behind ore and slag. Much of the town of Gedabey is built on copper, iron and possibly very low-grade gold ore, which is recognizable by its reddish colour all over the south and west of the town centre, even in children’s playgrounds. Slag is another important leftover from the old smelters. There is a huge slag heap on the river bank opposite the Russo-German school. During smelting work, the slag was just dumped there. The heap is so huge that it even has a few houses built on it. Some of the old mine structures were built of the slag, whereas the doors and arch-windows were shaped with red brick. Nevertheless, the people of Gedabey never use slag in building their houses but do use it to fine effect to decorate the walls of their yards.

The engineers used rock cut into a standard size to build the arches of the Gedabey-Qalakend railway. It was these viaducts that allowed the railway to pass through the mountainous terrain relatively easily. More than 20 arches of various sizes survive on the route. Some of them are in good enough condition to stand for another 100 years, but others require immediate preservation to prevent their complete collapse as a result of river and rain erosion and manmade destruction.

The 19th century heritage in Gedabey has been neglected, with the exception of a collection of Siemens exhibits, which features tools and equipment used at that time, pictures and dozens of articles and reports on the copper smelter and mine. The collection has been assembled by Etibar Aliyev, director of the House of Culture in Gedabey. The remaining infrastructure is left to the mercy of the elements and human activity. However, the German and Russian engineers built to last and we should be grateful for the quality of their construction. This prompts the question – would it be better for this proud heritage to survive on its own terms or to enjoy state protection?

About the author: Gani Nasirov was employed by a subcontractor of Gedabey Gold/Copper Processing Plant. In 2012-13, he worked as an assistant and translator in Gedabey. Currently, he is studying for an MA in Social Sciences at the University of Tartu in Estonia.

Bibliography

Feldenkirchen, Wildfried: Werner von Siemens: Inventor and International entrepreneur. Colombus, Ohio State University Press, 1994

Ibrahimov, Nazim: Azərbaycan tarixinin Alman səhifələri (German Pages in Azerbaijani History), Baku, Azerbaijan publishing house, 1997

Mammadova Fazila, Aliyev Etibar: Azərbaycanın əfsanələr paytaxtı: Gədəbəy – 2012 (Gedabey 2012: Capital of Legends in Azerbaijan). Baku, Propolis MMC 2012

Siemens, Werner von: Personal Recollections of Werner Von Siemens. New York: D. Appleton and Company 1893

Siemens.com, Siemens Company history, available at http://www.siemens.com/history/pool/en/history/1847-1865_beginnings_and_initial_expansion/company_history_long.pdf (accessed 16 July 2013)

Ulke, Titus, E.M: Modern electrolytic copper refining. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1903 Yusifov E.F., Tahmazov B.H: Ətraf mühit, iqtisadiyyat, həyat (The Environment, Economy, Life). Baku, El-Alliance, 2004