Pages 42-47

Pages 42-47by Dr. Suleyman Aliyarli

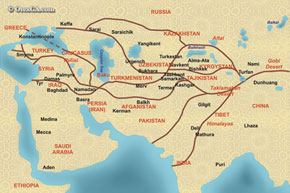

In the early medieval period and later, the Great Silk Road was a key economic factor connecting the empires of China, Byzantium and the Arab Caliphate, and dozens of countries that fell within the spheres of influence of these empires. This great network of cooperation covered southern and even northern parts of Europe too.

Within these immense boundaries, the Great Silk Road helped to develop towns, agriculture, private farming and silk production, and established land and sea transport routes. This was a unique economic process in the history of Eurasian civilization.

Azerbaijan and The Silk Road

Azerbaijan can be taken as an example to illustrate these arguments about the Great Silk Road. Azerbaijan serves as a bridge in the Caspian region, connecting the Caucasus, Middle East and north-eastern Europe.

Before the Mongolian wars, Azerbaijan, as a Caspian country, was one of the richest states in the Middle East. Medieval historian Hamdullah Qazvini (1280-1349) wrote that during the ´rule of the Seljuks and Atabays´ and also under the ´Shirvan shahs´ Azerbaijan´s annual state income stood at 25 million dinars. The state budgets of five neighbouring countries were: Arabian Iraq – 30 million dinars; Iraqi Ajam - 25 million dinars; Rum (Byzantium) – 15 million dinars; Georgia and Abkhazia - 5 million dinars; and Arminiyyat al-Akbar - only 2 million dinars. Another medieval scholar, Yaqut al-Hamavi (1179-1229), had earlier described the historical reality reflected in these figures as follows: ´Azerbaijan is a vast country and a great state´ (in Arabic: ´Azarbayjan balad kabir wa daula azim´.

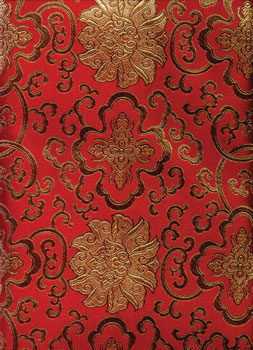

Such a strong economy had to be well founded. Among other reasons, the Great Silk Road and Azerbaijan´s own silk industry had played a great part. Marco Polo, who journeyed to the East in 1271-1291, wrote about Azerbaijan´s capital, Tabriz: ´Tauris [Tabriz] is a huge city… Its residents are engaged in trade and craftsmanship. They produce fine silk clothes, which are very expensive. Goods are brought in from India, Bodak (Baghdad), Mosul, Kremozor (the Bay of Hormuz), and other places. Latin merchants, especially those from Genoa, flood the city with their goods.´

Unlike today´s Iranian historians, Marco Polo did not call Tabriz an Iranian city. He wrote: ´Persia is 12 days´ travel from Tauris [Tabriz].´ This situation saw no substantial change in the 14th-15th centuries or afterwards. The only change was that Europeans started to make more trips to northern Azerbaijan for silk. Rui Gonzalez, while on his way home from Amir Timur´s (Tamerlane´s) capital Samarkand in the early 15th century, wrote: ´In Shamakhi, silk is produced in very large quantities. Even merchants from Genoa and Venice come here to buy silk.´ Ambrogio Contarini, a plenipotentiary envoy who was sent by the Republic of Venice to Agqoyunlu Sultan Uzun Hasan´s palace in Tabriz, said that in his country the Shamakhi (Shirvan)-made silk was known as ´Talaman silk´. As a Caspian state, Azerbaijan traded silk with Russia as well. With the emergence of capitalist manufacturing in Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries, the demand for Eastern raw materials and markets grew sharply. However, the route to the Indian Ocean via the Atlantic Ocean was controlled by the Portuguese, and the Ottoman Empire was in control of the route running through the Mediterranean and Black seas.

English merchants in Azerbaijan

At that time, the English made a surprise achievement in their attempts to gain access to India via the Caspian Sea. In 1561-63, Anthony Jenkinson visited Azerbaijan on behalf of the Muscovy Company and the British crown. He had been charged by Queen Elizabeth with securing a trade deal with Shah Tahmasib I, but he could not achieve this important objective. The shah refused to sign the agreement, as it could have damaged a peace agreement that had been reached with Sultan Suleyman Kanuni following years of war. In other words, the trade deal with the English could have undermined Safavid-Ottoman relations.

(Even a hundred years earlier, Tabriz preferred peace with the Ottomans to its relationship with the Europeans. Venetian diplomat Contarini said: ´The local Turks we met in Tabriz would tell each other: "These dogs have come here to divide Muhammad´s religion."´)

Back to Jenkinson. Despite his failure to sign a deal with Shah Tahmasib I, Jenkinson did secure a ´decree on privileges´ from the shah´s baylarbayi, or representative in Shirvan, Abdulla Khan Ustajli. The decree said: ´Considering the persistent requests by the gentle and dear envoy Antony Jenkinson, we, Abdulla Khan, who rule Shirvan and Hirkan, with the blessing of Allah, creator of the Earth and Heavens, have shown goodwill and kindness to bestow the following residents of the English City of London - Sir William Herr, Sir William Chester, Sir Thomas Loge, Mr Richard Mallory and Richard Chamberlain - and their trade company with full freedom, the right to cross freely [customs offices] and visit our country… to trade with cash or to barter goods, to stay in our country as long as they wish, and to leave the country freely whenever they wish.´

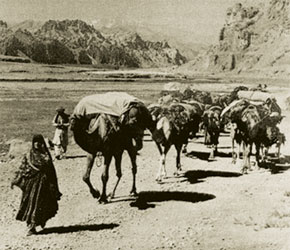

Benefiting from these favourable conditions, Jenkinson purchased bolts of silk and other goods and returned home. He was followed by another English company led by Thomas Alcock, who visited Azerbaijan for silk in 1563-67.

A third English trade delegation was led by Arthur Edwards (1565-67). After successful meetings with Shah Tahmasib I, he secured a decree from the shah on immunity for English merchants. In a letter sent to London from Shirvan, Arthur Edwards wrote: ´We have bought 11 bolts of raw silk, which we will send to England. The silk here is fine and of high quality.´

In 1568-69 Edwards, along with three other businessmen, visited Azerbaijan to buy silk. A fifth trade delegation led by Thomas Bannister and Jeffrey Decket visited Azerbaijan in 1569-74. A sixth delegation, led by Christopher Barrow, came in 1580. All of them came to Azerbaijan mostly for silk, and they all used the Volga-Caspian route.

There were two important factors that made these visits possible:

a) One of the old routes of the Great Silk Road ran through the Caspian Sea and Azerbaijan. In fact, this route has been in use throughout history. Guillaume de Rubruques, who was sent by French King Louis IX to meet the Mongolian Khan Mongke in 1253-55 (20 years before Marco Polo´s visit), returned to his country via this route - through the ´Edil Sea´ and the ´Iron Gate´ built by Alexander - from the north to the south. In 1474, Ambrogio Contarini, the Venetian envoy, led a large delegation from the south to the north (Tabriz-Shamakhi-Derbent). Even the Safavid envoy to Europe, Oruj bay Bayat, preferred this route.

b) Azerbaijan was an open country for trade and cooperation. It had an environment of religious and moral tolerance. The head of the German-Holstein embassy, Prof Adam Olearius (1636-39), also mentioned this. He said: ´Unlike Russia, Azerbaijan is not a closed country. By paying the required customs duty to the state, locals and foreigners can freely travel in the country. They can also do business and trade here.´

This assessment conforms with the aforementioned ´decree on privileges´ issued by Abdulla Khan Ustajli, the Safavi baylarbayi (representative) in Shirvan. Diplomat Contarini, meanwhile, noted the ´human factor´. He said: ´We left for the town of Derbent, which belonged to the Shirvan shah. We sometimes stayed in Turkish villages. We were welcomed in those villages… To be honest, the people there [in Azerbaijan] were very friendly. When asked who we were, we would reply: "We are Christians." And this answer would be enough for them.´

European diplomats and merchants preferred the Volga-Caspian route to the Black Sea route (via Georgia and Crimea), although the latter was shorter.

Silk and the Russian empire

Silk production has had a great role in the development of the silk industry and capitalist society in Russia. The Russian envoy to the Safavid state between 1715 and 1718, A. Volinskiy, wrote: ´There are many cattle, sheep and fish there [in northern Azerbaijan]. They [Azeris] are particularly engaged in silkworm breeding. Silkworms are bred everywhere in large quantities. Only a few villages near the seashore and the River Kur lack silk mills.´

Fifty years later, Academician Shamuil Gmelin wrote that there were nearly 1,500 silk-weaving looms and ´silk mills´ in Shamakhi. Another Russian spy, Serebrov Dzhulfinskiy, wrote 20 years later: ´In Shamakhi, almost every resident of the town has a workshop or is a silk weaver.´ The Russian occupation of Azerbaijan in the 19th century bought about fundamental changes in the country´s social and economic life. However, silk production and trade retained their importance. In 1850-70, silkworm production grew fivefold and reached 150,000 pounds (2,400 tons). The Nukha (Shaki) province accounted for 61,000 pounds of this.

Seventy-one per cent of the production was sold to Russian factories, and the rest to Europe. More than 200 European companies opened offices in the town of Shaki. Silkworms to the tune of 3 million roubles were sold to them in a year.

Shusha, Shamakhi and Jar-Balakan were also centres of silkworm breeding. Each province produced between 3,000 and 5,000 pounds of silkworms a year. Northern Azerbaijan accounted for 85 per cent of silkworms produced in the South Caucasus. It also accounted for 75 per cent (28,000 pounds) of silkworms required for Russian textiles (40,000 pounds).

As the demand for silkworms grew in Russia, new production facilities were established in Azerbaijan. In 1829, a silk mill was opened in Charabad, near the town of Shaki, by the Tsar´s Treasury. Two more mills of this kind were built by the Society to Promote the Silk Industry in Transcaucasia and local entrepreneur Muradkhanov. In 1850-60, French businessman Garni opened a modern mill in Shaki, which employed 400 people. An even larger mill with 350 workers and 220 master craftsmen was later opened by the Alekseyev and Voronin Brothers Company, which was owned by Moscow business people.

But these new factories could only produce raw material, namely silk thread. Clothes and dresses from silk were manufactured in Moscow and Ivanovo-Voznesensk. In other words, this was under the monopoly of the imperial centre as a result of the Tsarist government´s economic policy. Count Kankrin, who served as the finance minister under Tsar Nicholas I in the late 1820s, described the main points of this policy as follows: ´Transcaucasia is a very useful colony for Russian trade and industry. As a colony, it should provide our factories with raw materials (silkworms, cotton, etc.), and get manufactured goods from Russia in return.´

This is how the South Caucasus region was turned into an economic colony, a producer of raw materials and also a market for the output of Russian factories. It became a very productive colony.

By taking a look at the history of silk production and trade, we can also see some of the serious problems of the history of Azerbaijan, the Caucasus and the Middle East. For hundreds of years, the names of Tabriz, Shamakhi, Shaki and Arash - which are close to our heart – could be heard in the coffee houses of Venice, Marseilles and London. We owe this to the art of silk production. However, we have no moral right to boast about this or take pride in it. If today we are serious about developing the non-oil sector of our economy, and we really do need to think about this, we should not forget silk production, which has a long history in Azerbaijan. Otherwise, Azerbaijan will leave another of its national problems unresolved.

Literature:

Suleyman Aliyarli (editor), Sources of Azerbaijani History. Chiraq publishing house, Baku, in Azeri, 2007, pp. 183, 192, 246.

Suleyman Aliyarli (editor), The History of Azerbaijan: from the Distant Past to the 1870s. Azarbaycan publishing house, Baku, in Azeri, 1996, pp. 94, 715-16, 702-04.

I.P. Minayeva, Kniga Marko Polo, perevod starofrantsuzskogo teksta (Marco Polo´s Book, translated from the old French), Moscow, 1956, pp. 60, 65.

E.I. Shakhmaliyeva (editor), Z.I. Yampolskiy (compiler), Puteshestvenniki ob Azerbaydzhane (Travellers on Azerbaijan), Baku, 1961, pp 57, 91-93, 121.

Yu. V. Gotye, Angliyskiye puteshestvenniki v Moskovskom gosudarstve v XVI veke (English Travellers in the State of Muscovy in the 16th Century, translated from the English), pp. 91-92, 121.

M.K. Rozhkova, Ekonomicheskaya politika tsarskogo pravitelstva na Srednem Vostoke vo vtoroy chetverti XIX veka I russkaya burzhuaziya (Economic Policy of the Tsarist Government in the Middle East in the Second Quarter of the 19th Century and the Russian Bourgeoisie), Leningrad, 1949, pp 94-95.