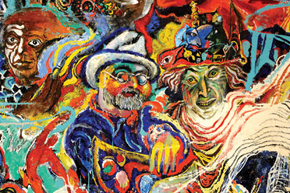

Eminent Azerbaijani artist Togrul Narimanbeyov (also known as Narimanbekov) synthesised east and west in his work, combining the decorativeness of eastern miniatures with the intellectuality of western art. His striking, colourful canvases now hang in some of the world’s best-known galleries, but early in his career, in the 1950s, he was criticised for “abandoning national style” and “going too far”.

From the late 1980s, Togrul began a peripatetic life, eventually settling in Paris. However, he returned frequently to his homeland, Azerbaijan. The interview below by art critic Mohbaddin Samad is based on his final conversations with the artist in Baku and Paris. Togrul Narimanbeyov passed away in Paris on 2 June 2013 at the age of 82. Following disagreement over whether he should be buried in France or Azerbaijan, the artist was finally laid to rest in Passy Cemetery in Paris on 3 July.

In Soviet times it was impossible to mention that your family had been repressed in the late 1930s. Can we touch on this topic now?

Of course, we can mention it. Our family comes from a generation of beys [nobility]. We are said to have had hectares of land and palaces in the Shusha region. Our relatives and family were highly educated people and were respected and famous intellectuals. My father was also an educated man. After graduating from the gymnasium school, he was sent to France in the 1920s by the Azerbaijani government to get higher education. He studied in Toulouse and majored in electric engineering. That is where he met and married my mother-to-be, Irma.

I would also like to say that my elder brother, People’s Artist of Azerbaijan Vidadi was born in Cayenne. My mother always used to say that our father was attached to his motherland. Despite living a wonderful life, he always wanted to come back to Azerbaijan. He thought that he should be near his father, that he had to support his parents in their old age. That is why one day my father took my mother and my older brother Vidadi and set off from Paris to Russia. Those were chaotic times in Russia. They had just had a revolution. That is why the ship sailed to Istanbul instead. When they arrived in Istanbul, they met another ship coming from Odessa, taking Russian emigrants to the West. One of the nobles, who was on that ship, knew my father and told him to return to France. My father ignored him, as he was in a hurry to see his family again. When he arrived in Baku, he was utterly astonished, because his grandfather, Amirbey Narimanbeyov, who had been governor-general of Baku, was now under house arrest and some of his relatives had been sent into exile.

So that was the situation in the country when he met my grandfather again. Soon after that, on 7 August 1930, I was born. My father and mother say that Grandfather Amirbey saw me and kissed me and died soon after that. Then my father started work. He got a responsible job at the State Project Enterprise. My father developed designs for many electric power stations. Those were very complicated times. People who had studied abroad would come under criticism for no reason. People wrote denunciations about them, which would be the basis for arrests. These poor people would be sentenced and sent to Siberia for a long time. My father was also arrested like this. He was sentenced to five years’ exile in Siberia, Marinskiy. I remained with my mother. However, my mother was also arrested after that. She was sent to the prison camp in Keshla [part of Baku].

I was five or six years old at the time. I can still remember everything. I remember that when my mother was being taken to the Keshla camp, she made a huge fuss and took me with her. They tried very hard at the camp to take me away from her, but in vain. My mother was a foreign citizen. So I turned seven in the camp. And I had to go to school, but it was impossible in the camp. My mother caused a huge racket as a foreign citizen and insisted that I go to school. Thanks to her persistence the chief of the prison camp took me to the first grade in school number 132. That is how I started my education. The chief of the camp took me to school and back every day in his personal Studebaker for a couple of years.

Then my mother was exiled to Kostanay, and from there to Karaganda [both in Kazakhstan]. After the war finished, my mother was allowed to live only in Samarkand [Uzbekistan], because Baku was a closed city back then.

I could not continue my education for some time after my mother was exiled to Karaganda. After a long time I was able to finish 7th grade and enter an art school with the help of my family and relatives. When I was at the art technical school, my mother had already been deported to Samarkand. One day I went there to see her and was very impressed by the architectural monuments from the ancient culture of Tamerlane. I thank God that I saw those unique monuments.

Early in their career, artists often choose another artist to follow as an example or join a movement. Did you do something similar?

I have always admired French Romanticism. Back then, when I was just starting out at the art technical school and then art university, my favourite artists were Eugène Delacroix and Gustave Courbet. I was also very interested in Cézannism. That is why I started studying it. Back then European artists were also inspired by the Cézanne school. This is probably why he had such an impact on the development of world art.

It is true that Cézannism also played an important role in my artistic career. But studying the national art of Azerbaijan and eastern culture played a bigger role in my personal development. I like the miniature art of Tabriz and Chinese and Japanese art a lot. It goes without saying that I managed to fully comprehend all of them through Azerbaijani art. As I already mentioned, the first time I understood it was when I visited Samarkand and saw the cultural monuments from Tamerlane’s times.

The truth is that whoever chooses others as idols or gets immersed in different movements at the beginning of their artistic careers must in the end return to their roots, because an artist becomes strong and invincible when he is both national and universal.

You started your career at a very difficult time – when the old was denied and banished and new movements appeared. It was probably not that easy for you to become an artist after such a difficult period in history, was it?

The first years of my career, as you said, were very chaotic and contradictory. That was when Socialist Realism prevailed in art. Moreover, artists were also required to engage in such political issues as “mobile exhibitions”. Do you understand what that means? This was a policy of limiting the creative independence of talented people and creating clichéd art pieces in a Socialist Realist style only.

However, we, the youth of the times, were constantly searching for novelty and progress. We focused all our attention on studying French avant-garde art. Cézanne, Van Gogh, Claude Monet, all the Impressionists and Expressionists were the favourite idols of all young artists.

There were also interesting developments in Russian avant-garde art. The Jack of Diamonds artistic society played a special role in this. I found the strength to study the work of this movement, which was so close to my heart. This had a great influence both on me and my creative development. However, I did not stray from my path. Using the advantages of these movements creatively, I developed as an artist based on national roots.

Nowadays many artists try to copy the European masters, while some prefer to create abstract pieces. What is your view of this as an experienced painter who is able to look at the artists of the world from both the eastern and western point of view?

As you travel around our world, get to meet different people, cultures and their art, you see how colourful, fresh and interesting they all are. Indeed, the cultures of different peoples of the world are beautiful in their uniqueness! I have always thought, and still do, that every artist has to discover the beauty of the culture of his own people and study its depths. They should not melt away in the culture of other nations by copying them.

Nowadays, art critics, artists and sculptors all over the world are sounding the alarm, insisting that art is regressing and being degraded. They doubt that there will ever again be new Leonardo da Vincis, Rafaels, Rembrandts or Modiglianis. Do you share your colleagues’ fears?

Yes, world art is degrading and regressing. I don’t know if you have noticed, but painting is starting to lose its value and specific features. Losing the quality that the Spanish and Italian people once achieved is turning into a sort of tradition.

From the very first day I lived in France I clearly felt and saw that they no longer have the eminent art and artists they once did. Despite the fact that they still have famous, leading masters in fashion, printing and architecture, they somehow seem to have lost these traditions specifically in fine arts.

I can now clearly see that television has taken over the fine arts. Television artists create works with glass tubes or such like for sheer effect. But this is no longer painting. Do you understand? It is not fine art!

I have noticed that our young generation is completely lost. They blindly run after Europe, thinking that they will be able to make financial gain by simply imitating them. However, they fail to understand that some European artists artificially create for commercial purposes. That is why everybody falls victim to this lie. They think that if a work of art is sold, it means that it is good, if it is not sold, then the work is bad.

In my opinion art will develop through the discovery and comprehension of eastern culture. Discovering the eastern cultures, all the ancient miniatures of Iran and Azerbaijan, as well as studying Chinese and Japanese culture in depth will stimulate the development and blossoming of world art.

One of your favourite artists, Van Gogh, is famous for his sunflowers, whereas you are known for your pomegranates. Is this the symbol of your career, or is there another significance to it?

The pomegranate is not only a symbol in my work, it is the principle and strength of my work. Through the pomegranate I want to express colour, form and energy to my viewers, to give them strength, as it were a performance-enhancing drug. The pomegranate represents all of this in terms of shades of colour, size and substance. When I draw a pomegranate, I want my audience to feel pleasure as if they were drinking the juice of that pomegranate. I want it to be a spring of life for them.

When you were young, you were passionate about singing. You used to sing to yourself while you worked. We saw you on many impressive stages – once on our opera stage, in Italy and elsewhere. Some called your performances dilettantism, others buffoonery. What would you say?

I don’t like dilettantism and don’t accept it as such. I think that if you are engaged in any type of art, be it painting, sculpture, singing or poetry, you always have to be on top of contemporary explorations. And you have to use all the capacities of the experts in that field. I graduated from music school. And when I was studying at the Art University in Vilnius, I also studied at the conservatoire at the same time. I did the same thing later when I travelled to Baku, Moscow, Boston, New York, Luxembourg and Paris. Singing has always been important to me as well as art.

I love singing so much, because it is a special form of art that has many riddles. Indeed, its riddles never end! Life has a strange and interesting philosophic rule: the more you are occupied with solving mysteries, the more you live.

You know very well that I have sacrificed a big part of my life to visual art. This is something more tangible, an art more earthy and for me painting bears fewer riddles. I have worked so much that, depending on where I start, I already know the result. However, it is hard to know that in singing. That is why I find singing very attractive at the moment.

You used to write poetry. Some of your poems have even been published. You were planning to publish a book of poems, but it hasn’t come off the press yet. Can you tell us why?

I swear there is no special reason. I simply need to bring together and sort through my writing. I have too many commissions in Paris, so I don’t have time for it. If things don’t change, publishing my poetry will be a task for the researchers, who will study my archives after I die (laughs).

You have known plenty of hardship. You lived in prison at the age of four to five. You found out what exile was with your mother. As if this was not enough, you were attacked several times during the Soviet period. What was the reason for this – your unconventional work or the fact that your family was repressed?

Visual art had many great difficulties under the totalitarian regime. Artists often faced such burdens. I remember that a large and important exhibition of Caucasus artists was to open in Moscow. This exhibition showcased works by artists from Azerbaijan, Georgia and Armenia. I went to that exhibition with a very good selection of my work.

The candidate member of the Politburo of the Soviet Union, USSR Culture Minister Yekaterina Furtseva, was also to attend the opening of the exhibition. The moment came and to the pomp of a military orchestra, she got out of her car and entered the exhibition hall. My paintings were hanging in an eye-catching spot, so she went straight up to them, stopped and said loudly: Comrades, Togrul Narimanbeyov’s works are on the road to surrealism and we cannot take this road. I cannot and will not allow it!

A dismayed hush fell. No one spoke, neither the members of her team, nor the organisers of the exhibition. Then one of the organisers of the exhibition, an artist, stepped bravely forward and said: Who are you? Are you from our Union of Artists or from outer space? This is our exhibition. We will show what we please. You are wrong. You have no right to interfere in our national culture.

Culture Minister Yekaterina Furtseva was furious and shouted: Get him out of here!

At that point Deputy Culture Minister Vladimir Ivanovich Popov saw me and pointed me out to Yekaterina Furtseva:

Yekaterina Alexandrovna, do you know which Narimanbeyov it is? Do you remember when I visited his workshop together with the French culture minister, André Malraux? André Malraux really liked his work and was very pleased with it. He even invited him to France.

After hearing all of this Yekaterina Furtseva said in a small voice: Then let’s go!

Thus she left me alone. If she hadn’t, my pieces would probably have been removed from the exhibition and she would have had a very bad opinion of me. I would probably have been kept out of art for a long time and would have gradually fallen out of shape.

I don’t think that the fact that my family was repressed in the 30s had anything to do with that episode. It turned out that this was the doing of my colleagues who were close to the minister, and did not accept me as such and were jealous of my talent.

When the former Soviet Union started to fall apart, you began your expatriate travels. You first went to Moscow, then to America, from there to Luxembourg and later to Paris. I know that you didn’t have your own apartment in any of those countries and always rented. What was the reason for these travels? A desire to see the world as an artist or a passion for art-business?

You know me very well and you know that I am very attached to my motherland. However, I am an artist who has no desire for earthly possessions. I have always breathed and lived art. The reason for living abroad was simply to measure the value of my art on an international scale. And I managed to measure it after a very long time.

To tell you the truth, even though my wife enjoys living abroad, I don’t particularly like living in foreign countries. Do you know why? Because people have no emotional bonds to each other in foreign countries. They are too cold towards each other. To be honest, this coldness gives me the shivers and saddens me. However, it is completely the opposite in Baku. People are very friendly.

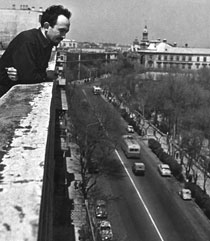

The artist looks out from his studio over Kommunisticheskaya Street, now Istiqlaliyyat, in central Baku

The artist looks out from his studio over Kommunisticheskaya Street, now Istiqlaliyyat, in central Baku

You have created several monumental murals in different places. I know that no artist can singlehandedly manage such monumental pieces of painting. They need strong “support”, a strong “hand”. I know that you have had such a hand and support. Could you elaborate on this, if it is not a secret?

You are quite right. Indeed, an artist cannot accomplish such great projects without help and support. Fortunately for me, I did have such great help. It was from the leader of Azerbaijan back then, Heydar Aliyev. He paid great attention to art and he always tried to direct my career towards the stage and murals.

I know for a fact that a Bernd Seizinger has acquired over 40 of your paintings and opened a Togrul Narimanbeyov private art museum in Princeton. The head of the country also proposed creating such a museum in Icheri Sheher [Baku’s old walled inner city]. But I feel as though this project is on hold…

I remember when Heydar Aliyev saw my new mural, he said: Togrul, you absolutely have to recreate the history of Icheri Sheher in your painting!

I was born in Icheri Sheher and lived here from the age of 13-14. I even painted my first pieces within these fortress walls. There were times when I drew the Shirvanshahs’ Palace and all the surrounding places on canvas over and over again. And now both my house and workshop are located here. Just as is in my youth, I still can’t get enough of painting Icheri Sheher.

Life has strange paradoxes. Our great dramatist Mirza Fatali Akhundov is buried in Tbilisi, Alimardan bey Topchubashov, Jeyhun Hajibeyli and Ummulbanin are in Paris and Mammadamin Rasulzade is in Ankara. Every Azerbaijani who lives away from home may face this unexpected reality of life. How do you feel about it?

I understand you. And in this regard I remember a poem by an Azerbaijani poet who is not very famous and whose name I have forgotten. The idea of the poem was something like this: If I die, bury me in the earth of my motherland. Let my body mix with the earth and add to it just a little.

I think this is a beautiful idea and I share it.

An earlier interview Globalization and genetic blood memory, or, a conversation with People’s Painter Togrul Narimanbeyov and an obituary Togrul Narimanbeyov – Global Azerbaijani Artist are also available on this website.

About the author: Art historian and critic Mohbaddin Samad is the author of two authoritative books on the artist – Togrul Narimanbeyov which was published in 1984 in Azerbaijani, Russian and English and Shukh ranglarin taranasi (Song of Bright Colours), published in 2012. He also wrote the script for an Azerbaijani TV documentary about the artist’s life.

From the late 1980s, Togrul began a peripatetic life, eventually settling in Paris. However, he returned frequently to his homeland, Azerbaijan. The interview below by art critic Mohbaddin Samad is based on his final conversations with the artist in Baku and Paris. Togrul Narimanbeyov passed away in Paris on 2 June 2013 at the age of 82. Following disagreement over whether he should be buried in France or Azerbaijan, the artist was finally laid to rest in Passy Cemetery in Paris on 3 July.

In Soviet times it was impossible to mention that your family had been repressed in the late 1930s. Can we touch on this topic now?

Of course, we can mention it. Our family comes from a generation of beys [nobility]. We are said to have had hectares of land and palaces in the Shusha region. Our relatives and family were highly educated people and were respected and famous intellectuals. My father was also an educated man. After graduating from the gymnasium school, he was sent to France in the 1920s by the Azerbaijani government to get higher education. He studied in Toulouse and majored in electric engineering. That is where he met and married my mother-to-be, Irma.

I would also like to say that my elder brother, People’s Artist of Azerbaijan Vidadi was born in Cayenne. My mother always used to say that our father was attached to his motherland. Despite living a wonderful life, he always wanted to come back to Azerbaijan. He thought that he should be near his father, that he had to support his parents in their old age. That is why one day my father took my mother and my older brother Vidadi and set off from Paris to Russia. Those were chaotic times in Russia. They had just had a revolution. That is why the ship sailed to Istanbul instead. When they arrived in Istanbul, they met another ship coming from Odessa, taking Russian emigrants to the West. One of the nobles, who was on that ship, knew my father and told him to return to France. My father ignored him, as he was in a hurry to see his family again. When he arrived in Baku, he was utterly astonished, because his grandfather, Amirbey Narimanbeyov, who had been governor-general of Baku, was now under house arrest and some of his relatives had been sent into exile.

So that was the situation in the country when he met my grandfather again. Soon after that, on 7 August 1930, I was born. My father and mother say that Grandfather Amirbey saw me and kissed me and died soon after that. Then my father started work. He got a responsible job at the State Project Enterprise. My father developed designs for many electric power stations. Those were very complicated times. People who had studied abroad would come under criticism for no reason. People wrote denunciations about them, which would be the basis for arrests. These poor people would be sentenced and sent to Siberia for a long time. My father was also arrested like this. He was sentenced to five years’ exile in Siberia, Marinskiy. I remained with my mother. However, my mother was also arrested after that. She was sent to the prison camp in Keshla [part of Baku].

I was five or six years old at the time. I can still remember everything. I remember that when my mother was being taken to the Keshla camp, she made a huge fuss and took me with her. They tried very hard at the camp to take me away from her, but in vain. My mother was a foreign citizen. So I turned seven in the camp. And I had to go to school, but it was impossible in the camp. My mother caused a huge racket as a foreign citizen and insisted that I go to school. Thanks to her persistence the chief of the prison camp took me to the first grade in school number 132. That is how I started my education. The chief of the camp took me to school and back every day in his personal Studebaker for a couple of years.

Then my mother was exiled to Kostanay, and from there to Karaganda [both in Kazakhstan]. After the war finished, my mother was allowed to live only in Samarkand [Uzbekistan], because Baku was a closed city back then.

I could not continue my education for some time after my mother was exiled to Karaganda. After a long time I was able to finish 7th grade and enter an art school with the help of my family and relatives. When I was at the art technical school, my mother had already been deported to Samarkand. One day I went there to see her and was very impressed by the architectural monuments from the ancient culture of Tamerlane. I thank God that I saw those unique monuments.

Early in their career, artists often choose another artist to follow as an example or join a movement. Did you do something similar?

I have always admired French Romanticism. Back then, when I was just starting out at the art technical school and then art university, my favourite artists were Eugène Delacroix and Gustave Courbet. I was also very interested in Cézannism. That is why I started studying it. Back then European artists were also inspired by the Cézanne school. This is probably why he had such an impact on the development of world art.

It is true that Cézannism also played an important role in my artistic career. But studying the national art of Azerbaijan and eastern culture played a bigger role in my personal development. I like the miniature art of Tabriz and Chinese and Japanese art a lot. It goes without saying that I managed to fully comprehend all of them through Azerbaijani art. As I already mentioned, the first time I understood it was when I visited Samarkand and saw the cultural monuments from Tamerlane’s times.

The truth is that whoever chooses others as idols or gets immersed in different movements at the beginning of their artistic careers must in the end return to their roots, because an artist becomes strong and invincible when he is both national and universal.

You started your career at a very difficult time – when the old was denied and banished and new movements appeared. It was probably not that easy for you to become an artist after such a difficult period in history, was it?

The first years of my career, as you said, were very chaotic and contradictory. That was when Socialist Realism prevailed in art. Moreover, artists were also required to engage in such political issues as “mobile exhibitions”. Do you understand what that means? This was a policy of limiting the creative independence of talented people and creating clichéd art pieces in a Socialist Realist style only.

However, we, the youth of the times, were constantly searching for novelty and progress. We focused all our attention on studying French avant-garde art. Cézanne, Van Gogh, Claude Monet, all the Impressionists and Expressionists were the favourite idols of all young artists.

There were also interesting developments in Russian avant-garde art. The Jack of Diamonds artistic society played a special role in this. I found the strength to study the work of this movement, which was so close to my heart. This had a great influence both on me and my creative development. However, I did not stray from my path. Using the advantages of these movements creatively, I developed as an artist based on national roots.

Nowadays many artists try to copy the European masters, while some prefer to create abstract pieces. What is your view of this as an experienced painter who is able to look at the artists of the world from both the eastern and western point of view?

As you travel around our world, get to meet different people, cultures and their art, you see how colourful, fresh and interesting they all are. Indeed, the cultures of different peoples of the world are beautiful in their uniqueness! I have always thought, and still do, that every artist has to discover the beauty of the culture of his own people and study its depths. They should not melt away in the culture of other nations by copying them.

Nowadays, art critics, artists and sculptors all over the world are sounding the alarm, insisting that art is regressing and being degraded. They doubt that there will ever again be new Leonardo da Vincis, Rafaels, Rembrandts or Modiglianis. Do you share your colleagues’ fears?

Yes, world art is degrading and regressing. I don’t know if you have noticed, but painting is starting to lose its value and specific features. Losing the quality that the Spanish and Italian people once achieved is turning into a sort of tradition.

From the very first day I lived in France I clearly felt and saw that they no longer have the eminent art and artists they once did. Despite the fact that they still have famous, leading masters in fashion, printing and architecture, they somehow seem to have lost these traditions specifically in fine arts.

I can now clearly see that television has taken over the fine arts. Television artists create works with glass tubes or such like for sheer effect. But this is no longer painting. Do you understand? It is not fine art!

I have noticed that our young generation is completely lost. They blindly run after Europe, thinking that they will be able to make financial gain by simply imitating them. However, they fail to understand that some European artists artificially create for commercial purposes. That is why everybody falls victim to this lie. They think that if a work of art is sold, it means that it is good, if it is not sold, then the work is bad.

In my opinion art will develop through the discovery and comprehension of eastern culture. Discovering the eastern cultures, all the ancient miniatures of Iran and Azerbaijan, as well as studying Chinese and Japanese culture in depth will stimulate the development and blossoming of world art.

One of your favourite artists, Van Gogh, is famous for his sunflowers, whereas you are known for your pomegranates. Is this the symbol of your career, or is there another significance to it?

The pomegranate is not only a symbol in my work, it is the principle and strength of my work. Through the pomegranate I want to express colour, form and energy to my viewers, to give them strength, as it were a performance-enhancing drug. The pomegranate represents all of this in terms of shades of colour, size and substance. When I draw a pomegranate, I want my audience to feel pleasure as if they were drinking the juice of that pomegranate. I want it to be a spring of life for them.

When you were young, you were passionate about singing. You used to sing to yourself while you worked. We saw you on many impressive stages – once on our opera stage, in Italy and elsewhere. Some called your performances dilettantism, others buffoonery. What would you say?

I don’t like dilettantism and don’t accept it as such. I think that if you are engaged in any type of art, be it painting, sculpture, singing or poetry, you always have to be on top of contemporary explorations. And you have to use all the capacities of the experts in that field. I graduated from music school. And when I was studying at the Art University in Vilnius, I also studied at the conservatoire at the same time. I did the same thing later when I travelled to Baku, Moscow, Boston, New York, Luxembourg and Paris. Singing has always been important to me as well as art.

I love singing so much, because it is a special form of art that has many riddles. Indeed, its riddles never end! Life has a strange and interesting philosophic rule: the more you are occupied with solving mysteries, the more you live.

You know very well that I have sacrificed a big part of my life to visual art. This is something more tangible, an art more earthy and for me painting bears fewer riddles. I have worked so much that, depending on where I start, I already know the result. However, it is hard to know that in singing. That is why I find singing very attractive at the moment.

You used to write poetry. Some of your poems have even been published. You were planning to publish a book of poems, but it hasn’t come off the press yet. Can you tell us why?

I swear there is no special reason. I simply need to bring together and sort through my writing. I have too many commissions in Paris, so I don’t have time for it. If things don’t change, publishing my poetry will be a task for the researchers, who will study my archives after I die (laughs).

You have known plenty of hardship. You lived in prison at the age of four to five. You found out what exile was with your mother. As if this was not enough, you were attacked several times during the Soviet period. What was the reason for this – your unconventional work or the fact that your family was repressed?

Visual art had many great difficulties under the totalitarian regime. Artists often faced such burdens. I remember that a large and important exhibition of Caucasus artists was to open in Moscow. This exhibition showcased works by artists from Azerbaijan, Georgia and Armenia. I went to that exhibition with a very good selection of my work.

The candidate member of the Politburo of the Soviet Union, USSR Culture Minister Yekaterina Furtseva, was also to attend the opening of the exhibition. The moment came and to the pomp of a military orchestra, she got out of her car and entered the exhibition hall. My paintings were hanging in an eye-catching spot, so she went straight up to them, stopped and said loudly: Comrades, Togrul Narimanbeyov’s works are on the road to surrealism and we cannot take this road. I cannot and will not allow it!

A dismayed hush fell. No one spoke, neither the members of her team, nor the organisers of the exhibition. Then one of the organisers of the exhibition, an artist, stepped bravely forward and said: Who are you? Are you from our Union of Artists or from outer space? This is our exhibition. We will show what we please. You are wrong. You have no right to interfere in our national culture.

Culture Minister Yekaterina Furtseva was furious and shouted: Get him out of here!

At that point Deputy Culture Minister Vladimir Ivanovich Popov saw me and pointed me out to Yekaterina Furtseva:

Yekaterina Alexandrovna, do you know which Narimanbeyov it is? Do you remember when I visited his workshop together with the French culture minister, André Malraux? André Malraux really liked his work and was very pleased with it. He even invited him to France.

After hearing all of this Yekaterina Furtseva said in a small voice: Then let’s go!

Thus she left me alone. If she hadn’t, my pieces would probably have been removed from the exhibition and she would have had a very bad opinion of me. I would probably have been kept out of art for a long time and would have gradually fallen out of shape.

I don’t think that the fact that my family was repressed in the 30s had anything to do with that episode. It turned out that this was the doing of my colleagues who were close to the minister, and did not accept me as such and were jealous of my talent.

When the former Soviet Union started to fall apart, you began your expatriate travels. You first went to Moscow, then to America, from there to Luxembourg and later to Paris. I know that you didn’t have your own apartment in any of those countries and always rented. What was the reason for these travels? A desire to see the world as an artist or a passion for art-business?

You know me very well and you know that I am very attached to my motherland. However, I am an artist who has no desire for earthly possessions. I have always breathed and lived art. The reason for living abroad was simply to measure the value of my art on an international scale. And I managed to measure it after a very long time.

To tell you the truth, even though my wife enjoys living abroad, I don’t particularly like living in foreign countries. Do you know why? Because people have no emotional bonds to each other in foreign countries. They are too cold towards each other. To be honest, this coldness gives me the shivers and saddens me. However, it is completely the opposite in Baku. People are very friendly.

The artist looks out from his studio over Kommunisticheskaya Street, now Istiqlaliyyat, in central Baku

The artist looks out from his studio over Kommunisticheskaya Street, now Istiqlaliyyat, in central Baku You have created several monumental murals in different places. I know that no artist can singlehandedly manage such monumental pieces of painting. They need strong “support”, a strong “hand”. I know that you have had such a hand and support. Could you elaborate on this, if it is not a secret?

You are quite right. Indeed, an artist cannot accomplish such great projects without help and support. Fortunately for me, I did have such great help. It was from the leader of Azerbaijan back then, Heydar Aliyev. He paid great attention to art and he always tried to direct my career towards the stage and murals.

I know for a fact that a Bernd Seizinger has acquired over 40 of your paintings and opened a Togrul Narimanbeyov private art museum in Princeton. The head of the country also proposed creating such a museum in Icheri Sheher [Baku’s old walled inner city]. But I feel as though this project is on hold…

I remember when Heydar Aliyev saw my new mural, he said: Togrul, you absolutely have to recreate the history of Icheri Sheher in your painting!

I was born in Icheri Sheher and lived here from the age of 13-14. I even painted my first pieces within these fortress walls. There were times when I drew the Shirvanshahs’ Palace and all the surrounding places on canvas over and over again. And now both my house and workshop are located here. Just as is in my youth, I still can’t get enough of painting Icheri Sheher.

Life has strange paradoxes. Our great dramatist Mirza Fatali Akhundov is buried in Tbilisi, Alimardan bey Topchubashov, Jeyhun Hajibeyli and Ummulbanin are in Paris and Mammadamin Rasulzade is in Ankara. Every Azerbaijani who lives away from home may face this unexpected reality of life. How do you feel about it?

I understand you. And in this regard I remember a poem by an Azerbaijani poet who is not very famous and whose name I have forgotten. The idea of the poem was something like this: If I die, bury me in the earth of my motherland. Let my body mix with the earth and add to it just a little.

I think this is a beautiful idea and I share it.

An earlier interview Globalization and genetic blood memory, or, a conversation with People’s Painter Togrul Narimanbeyov and an obituary Togrul Narimanbeyov – Global Azerbaijani Artist are also available on this website.

About the author: Art historian and critic Mohbaddin Samad is the author of two authoritative books on the artist – Togrul Narimanbeyov which was published in 1984 in Azerbaijani, Russian and English and Shukh ranglarin taranasi (Song of Bright Colours), published in 2012. He also wrote the script for an Azerbaijani TV documentary about the artist’s life.