There is a proverb in Azerbaijan – “however much you say halva, it won’t make your mouth sweet.” And if you have ever tried Sheki halva, then it will have made your mouth and even your soul very sweet indeed. In a country renowned for its sweet tooth, Sheki halva is the most sugary of confections. In the last issue of Visions, we explained how to enjoy Sheki’s signature savoury dish, piti, and promised to reveal this time around the secrets of the town’s signature sweet.

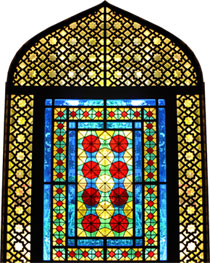

Visiting Sheki, we were struck by the resemblance between the famous halva and another of the town’s trademarks – shebeke – a wooden lattice of stained glass. So what do halva and shebeke have in common? First of all, they both belong to Sheki. Second, their patterns are similar and can be considered Sheki’s “visiting card”. And third, both are hand-made. Only a professional pastry chef can make real Sheki halva and only a craftsman can create real Sheki shebeke.

STAINED GLASS

Shebeke is a wooden lattice of pieces of coloured glass, held together without glue or a single nail. The word shebeke comes from the Arabic and means web. Many restaurants, public places and even private houses in Sheki are decorated with shebeke. As Huseyn Hajimustafayev, a shebeke craftsman of almost 25-years’ experience, told Visions, it’s because shebeke windows bring colour and life to any building. Indeed, the play of coloured light inside those buildings gives them a special, mysterious air. These beautiful, intricate panels are usually made from the wood of plane trees assembled like a giant puzzle of thousands of pieces. Each wooden frame is cut and pieced together without nails or screws and then the glass is cut to fit into this latticework frame, a painstaking process described here by Huseyn Hajimustafayev:

First I need to prepare a sketch and then to assemble the wooden base. The measurements must be precise to the millimetre or the whole thing will have to be scrapped. Usually, the spaces are filled with pieces of coloured glass, but sometimes just the wooden frame is used. Graceful geometrical motifs are the most common. Each piece is cut 12 times. So, it takes at least five months to make a small shebeke frame 130 by 130 centimetres.

A JEWELLER’S ART

It’s also true that a shebeke craftsman is like a jeweller. The technique is complex and known only to a few artisans who pass their meticulous craft from generation to generation. Huseyn Hajimustafayev is one of them and teaches young apprentices who wish one day to become professional shebeke makers. Craftsman Huseyn told us that several of his pieces have received awards at various exhibitions. For instance, his spherical shebeke took first place in the International Muscat Festival in Oman last year.

The main thing in the craft of shebeke is knowledge of geometry, which young students should have from the outset. They should also be patient, as they need to be precise. A professional master craftsman is never in a hurry. He should be careful while making shebeke like a spider spinning a web.

One of the most distinctive features of the Khan’s Palace in Sheki is the shebeke in the building’s windows. We were told that during the era of the khans (late 18th century), Venetian glass was ordered especially for the shebeke and was a catalyst for relations between Europe and the Sheki khanate.

SWEET PATTERN

When you look at a large piece of Sheki halva, you will see an intricate lattice pattern on the top, reminiscent of shebeke. So what lies beneath the pattern? It’s a confection of hazelnuts, walnuts, butter, sugar, rice flour and spices. And most importantly, halva is the pride of Sheki. Whenever an Azerbaijani visits Sheki, they are sure to bring back at least one box of halva. Then relaxing at home, they will sip freshly brewed tea, savour the halva and remember their trip.

TRADE SECRET

The complexity of making Sheki halva means that it is one sweet that is not made at home. If you do find a home-made Sheki halva, it won’t be the real thing. It’s not so easy to make halva and only a few people who live in Sheki know its secret. Halva is made in family businesses, in which the recipe has been passed down from generation to generation for over 200 years. Halva makers, known as halvachi, carefully guard the secret formula for cooking lattices, grinding nuts and making syrup. “It’s the family’s trade secret,” they say.

YAKHYA HALVACHI

The Samedov brothers from Sheki have been making halva for seven generations, so their family is considered one of the oldest in the halva business. One of the brothers, Abulfaz Samedov, invited Visions to their bakery to see the real process of making halva. His ancestors’ pictures hang in the bakery to honour the family tradition. And indeed, it was a Samedov who pioneered the making of halva in Sheki. He was called Yakhya, so the bakery is named after him. “Welcome to Yakhya halvachi,” Abulfaz said in greeting as we were about to enter his small “halva factory”.

Actually, there are many stories about the origins of halva in Sheki. According to one of them, the Sheki khan loved sweets and wanted to surprise some foreign visitors to his palace. He ordered his cooks to make something very sweet and delicious on pain of death. The cooks decided to make the halva that had recently become known as Sheki halva. The khan was very taken with it and spared the cooks’ lives. However, Abulfaz has a different story for the emergence of halva. He says that really halva came to Sheki from Tabriz, an Azerbaijani city now in north-west Iran. A Tabriz merchant called Mashadi Huseyn settled in Sheki, where he shared the halva recipe with local merchants who became halvachi. Though perhaps both stories are true – maybe Mashadi Huseyn brought the recipe and the khan gave it his seal of approval.

FOLLOWING A BIRD’S FEATHER

Abulfaz says that it usually takes a whole day to bake halva. First, spices and ingredients for the filling have to be carefully prepared. Mainly, hazelnuts and walnuts are used with some crushed coriander and cardamom seeds. The smell is something else! Then dough is made from rice flour and cooked on a saj, a convex iron griddle. Abulfaz’s cousin Vusal scoops up the dough in a special cup with tiny holes in the bottom and pours it quickly, zigzagging in different directions over the hot saj. The delicate threads of dough form a latticework pattern on the griddle and cook very quickly. The thin webs are ready to be removed from the saj after a minute. Vusal makes hundreds of them every day. It cannot be easy to spend the whole day over a hot griddle, but Vusal enjoys his work. He says that only a few people make real halva in Sheki, so he is considered a master. Then it is time to assemble the halva. Usually six layers of the dough webs form the base. They are filled with the nut and spice mixture and topped with more layers of dough webs. Once the halva has been put together, Abulfaz creates the distinctive red pattern on top. It’s spectacular to watch. The patterns on Sheki halva are made with a bird’s feather. Abulfaz says that it takes an observant eye to create the patterns with geometric accuracy, as in shebeke. The distinctive red dye is made from a mixture of saffron, dried carrot and beetroot. The halva is then placed on a saj over hot coals where it cooks for up to 10 minutes.

Finally, the halva is removed from the heat, and sugar syrup or, in a more luxurious version of the sweet, honey, is poured over it. The halva is left to stand while the syrup is absorbed, then it is ready to eat. As the sweetness plays over your taste buds, you will see in your mind’s eye the play of colours as light shines through the shebeke of mysterious, alluring Sheki.