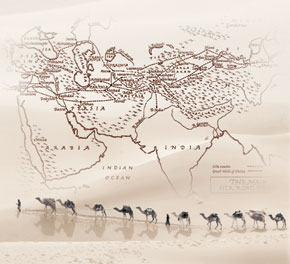

The cities of Azerbaijan have been part of the pattern of trade and other ties between East and West through the ages. The linking route of the great Silk Road changed as regional powers waxed and waned, having a direct influence on the development of cities as centres of crafts and trade. Cities blossomed as trade came their way, then withered as the Silk Road changed direction. This was the fate of Azerbaijani cities such Beylaqan, Qabala, Shabran and Aresh, which declined and disappeared from history as the Silk Road itself fell into decline.

Silk was a precious commodity and the mainstay of Caucasian-European trade, bringing the two different worlds – East and West – together. For hundreds of years, the babble of multilingual bazaars was heard all along the Silk Road, for hundreds of years, merchants carried their silk and gems, spices and dyes, gold and silver, carpets and rugs along the dusty roads to sell in Europe. Most goods travelled along the Silk Road from East to West. Silk was highly prized in Europe, improving personal hygiene, while spices were widely used in the production of medicines and preservation of food.

Merchants, an important social stratum in any city, were the passionate adventurers of their time. The caravan trade could bring in huge profits, but bore equally huge risks. That's why merchants sought to trade not alone but in large caravans of hundreds, or thousands, of armed men. The journey from the Eastern Mediterranean to China and back usually took several years.

A branch of the Silk Road that passed through the Caucasus started in Central Asia, in Sogdiana and its capital Marakanda (Samarkand in modern-day Uzbekistan). The road led west to the Khorezm region (capital Khiva) and passed around the north of the Caspian Sea. It traversed the steppes to the north of the Caucasus and then crossed the mountains through the Klukhoris and Marukhi passes and went down to the Black Sea coastal city of Sukhumi. From here the caravans crossed the Black Sea to Constantinople. The Caucasian Silk Route grew in importance in the second half of the 6th century, when the Sassanid Empire closed the passage of caravans through its territory to the Byzantine Empire.

Caravanserais and connections

Trade along the Silk Road stimulated the development of cities in the medieval East. While cities in Western Europe mainly served local markets, cities in Asia served international trade. These cities, including those of Azerbaijan, had caravanserais, which combined the functions of hotel and warehouse. Special bazaars were held for foreign merchants. The caravans created work for people of many professions – camel drivers, guards, moneychangers and so on, helping to shape the development of the trading cities. Through ancient and medieval periods, Azerbaijan was at the crossroads of three civilizations – the old Christian Mediterranean, Zoroastrian Iranian and Muslim Turkic.

While the Eastern Christian and Sassanid (Iranian)-Zoroastrian civilizations dominated trade and politics in the early medieval period, by the middle of the 7th century the strengthening Muslim civilization began to control the dynamic of contacts. In the first half of the 8th century, all the Western routes of the Great Silk Road came under the control of the Caliphate. China lost control of Central Asia, following its defeat by the Arab army at the Battle of Talas in 751. From that time on, the caravan trade was almost completely monopolised by Muslim and Jewish merchants.

Several important caravan routes passed through Azerbaijan. Ninth-century Persian geographer Ibn Khordadbeh said one of the branches of the Khorasan road was particularly valuable, as it connected the distant northern provinces of the Caliphate – Arran, Azerbaijan – with lands both near and far.

Maragha, in what is now eastern Iran, was one of the most important transportation hubs. Roads radiated from Maragha – one went north through Tabriz to Marandi, where it split in two, one road leading to Khoy and the other to Nashavu in modern-day Nakhchivan and beyond. There were also roads from all of these points to Ardabil. Here they converged into a single route to the north – to Barda, the centre of Arran province.

In the Arab period, many cities developed around a central square, once a feature of Greek cities; these included Barda, Shamkir, Beylaqan, Nakhchivan and Derbent, all except the last in the modern-day Azerbaijan Republic, and Ardabil, Sarab, Tabriz, Marand and Salmas, in the Azerbaijani regions of Iran. These cities all had economic and cultural ties with the great centres of the medieval East – Baghdad, Damascus and Basra.

Golden age – sanitation and literature

The 11th and 12th centuries are recorded in history as the ‘golden age’ of the cities of Azerbaijan, a phenomenal era. These cities were large, with populations of hundreds of thousands. Up to 500,000 people lived in Ganja at a time when cities of 20,000 to 30,000 were considered large in Europe. As the cities developed, so did handicrafts in Azerbaijan, which had some 30-40 different craft professions.

One renowned craft was minasazi, the decoration of precious stones, and the products of these crafts, especially stained glass, were distributed over a wide area. Underwater archaeology along the Azerbaijani coast of the Caspian Sea has found large quantities of the ceramics that were being shipped to various countries.

Another valuable trading product was kermes, a red dye made from insects. The dye was used in textiles and especially carpet weaving. Arabic sources referred to it as girmiz and the 10th century Persian geographer Al-Istakhri wrote that girmiz was exported from Barda to India and elsewhere.

As cities developed, they tended to specialise and market cities and port cities emerged. Urban life became markedly different from village life. Relatively efficient utilities were established; sources report on urban sewage systems and ceramic water supply pipes. Houses were often built with gypsum and fired brick with ceramic facings. The governors of the great empires frequently had their residences in the medieval cities. A country’s political independence enabled brisk trade relations and was a crucial factor in the level of its cities’ socio-economic prosperity.

The main trail of Eurasian transit trade criss-crossed Azerbaijani lands, passing through the expanding cities. This in turn seeded the development and prosperity of secular culture. Only this can explain the historical circumstances that produced the great thinkers and poets of the ‘golden age’, primarily Nizami Ganjavi, Khaqani Shirvani and Mehseti Ganjavi. The cultural environment generated interest in the past. Kitabi Dada Qorqud (The Book of Dada Qorqud, also written also written Dede Gorgud and Dede Korkut), which was put into written form in the 12th century, is today a principal source of the older history of Azerbaijan; an encyclopaedia of its distant past and medieval life. Just as it is not possible to study the distant past of the modern Greeks without the Iliad and Odyssey, European history without the legends of the Nibelungs and the Song of Roland, so it is impossible to study the origins and history of the Oghuz Turks without Kitabi Dada Qorqud.

Stability and storm

The Mongols maintained a unified system of control across almost all the Eurasian trade routes for a century and a half. However, after Genghis Khan's death, the empire quickly disintegrated. The Chingizid successor states formed a quartet of empires, which claimed separate areas of the trade routes from each other. Thus, Azerbaijan became the scene of constant fighting between khans of the Golden Horde and Hulagu’s armies; naturally, the cities were badly affected, and they became centres of organised resistance. The Mongols were merciless in such cases; the population of a resisting city would be totally annihilated. All that had been created by many generations – the traditions of urban development, irrigation systems, ceramic piping systems, palaces, bridges and caravanserais – would also be destroyed and consigned to oblivion. Survivors hid in the mountains and forests.

Ibn al-Athir, a celebrated 13th century Arab historian and eyewitness of the total destruction wreaked by the Mongols, described the effect:

The greatest tragedy described in history was Nebuchadnezzar’s attack on the Israelites when he assaulted and destroyed Jerusalem. But what is Jerusalem compared with the cities destroyed by the Mongols? In each of these cities, whose population was completely wiped out, the number of dead exceeded the population of Jerusalem several times over. No city, except for Tabriz, the capital of Hulagu’s state, could compare with them, either in size of population or in craft production.

Timur’s (Tamerlane’s) attempts to reunite the main Eurasian trade routes within his empire were temporarily successful. Merchants taking the southern road were once more under reliable protection. However, during his campaign against the Golden Horde, Timur practically wiped out all the trade cities around the northern Caspian and the Black seas, and the northern route was abandoned. Timur’s descendants were unable to preserve a centralised state and eventually the southern route, too, virtually ceased to function.

From ships of the desert to silk by sea

In the 15th and 16th centuries, maritime trade became more attractive than the overland caravan routes, which were by now dangerous. The Volga-Caspian trade route was developed and adopted by Russian and English merchants. From that time, Azerbaijani cities (Shamakhi, Derbent, Baku, Ardabil, Tabriz, Maragha, Ganja, Nakhchivan) grew in importance. This was not only due to their proximity to the Great Silk Road.

At different periods of history, Azerbaijan was an imperial centre for the Atabeys, Hulagids, Agqoyunlu, and Safavids. And this was reflected in the social and economic shape of its cities, especially its capitals.

The silk trade was always a central subject of negotiation in diplomatic relations between the Safavid state, European countries and Russia. The raw silk trade was so lucrative that Shah Abbas I established a state monopoly over it and European travellers called him the ‘richest monarch in the world’. All trade within the Safavid state was divided between the Shah’s huge operation and that of other merchants. The government itself organised the international caravan trade. However, Shah Safi I (1629-1642) eliminated the monopoly and banned government officials from intervening in the raw silk trade.

Thus private trade in silk was revived and cocoon production benefited. Adam Olearius was a member of an embassy sent by the duke of Holstein-Gottorp to Moscow and Persia, whose purpose was to conclude agreements with the two countries on conducting the silk trade through Moscow into Holstein, a convenient location for onward trade through the Baltic and North Sea. As a member of this embassy, Olearius twice visited the Moscow region and Azerbaijan between 1636 and 1639 and he recorded that more than 20,000 cocoons were produced in productive years in Azerbaijan. Thousands of bags of silk were used domestically while the rest were exported.

Always open – and hospitable

Sources of that time indicate that Azerbaijan was a land ‘open’ to trade and establishing business contacts. Religious and spiritual tolerance was customary. Here there is a very interesting message in Adam Olearius’s description:

Azerbaijan is not a closed country like Russia. The local people and foreigners who have paid the required state duties can enter and leave the country freely. They can also engage in trade and craft.

Olearius also witnessed the ‘human factor’: The people treated us very kindly and were friendly: they brought us milk to drink.

A 15th century Venetian diplomat Ambrogio Contarini, in turn, wrote: From Shamakhi we went to the town of Derbent, belonging to Shirvan, and continued on the way, stopping from time to time in the Turkish (Turkic) settlements, where we were received very well. Halfway there is a small, quite beautiful town (Quba) where so many wonderful fruits grew, especially apples, looking at them you do not believe your own eyes.

Contarini noted further: ...the need to give full justice to the local people, who appeared to be among the kindest, for during our stay there they did not cause us the slightest insult. To the question of who we are, we answered simply: - Christians, and this response was enough for them.

One further example of the tradition of Muslim religious tolerance in these parts.

Literature

1. S. Aliyarli (ed.). Sources on the History of Azerbaijan. Second edition. Baku, 2007

2. S. Aliyarli (ed.). The History of Azerbaijan. From Ancient Times to the 1870s. Second edition. Baku, 2009

3. E. Muradaliyeva. Cities of the Caucasus on the Great Silk Road. Institute of Strategic Studies of the Caucasus. Baku, 2011

4. E. M. Shahmaliyeva (ed.). Travellers on Azerbaijan. Vol.1. Baku, 1961

About the author: Professor Elmira Muradaliyeva PhD Historical Sciences, works at Baku State University. She is the author of books and articles on the history of the cities of Azerbaijan.