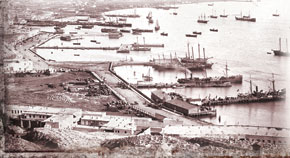

A myriad of companies, large and small, sprung up during Baku’s first oil boom in the 19th century. Though rivalry was often fierce, the oil industrialists soon realised that they could advance many of their interests better through co-operation than competition. Thus, the first Congress of Baku Oil Industrialists was held from 26 October to 8 November 1884. The congresses continued to function more or less every year up to the Bolshevik revolution of 1917. At that time Baku was part of imperial Russia and the biggest names in the empire’s oil industry – the Nobels and Rothschilds – took part in the Baku congresses, a sign of the meetings’ importance.

Representatives of the Nobel Brothers Petroleum Production Company (abbreviated to Branobel, the company’s telegram address) regularly attended from the second congress onwards. Emanuel Nobel, who took over management of Branobel in 1888 after his father Ludvig’s death, was an especially active participant.

The Russian government always sent a high-ranking representative – the minister of state property, the minister of the economy or the minister of railways.

Win-win

The congresses served the interests of all sides – they helped businessmen to co-ordinate and organise their work, enabling them “to express before the government their needs, aspirations and desires”. However, they also simplified the government’s work, as it was much more convenient for the authorities to deal with the leaders and representatives of the oil companies when they were gathered together in one place and to keep an eye on what they were up to.

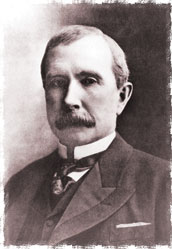

In the other major oil power of the time, the USA, the government was equally keen to help the development of its oil industry, as it understood the importance of the oil industrialists’ work. The founder of US giant Standard Oil, John D. Rockefeller, commented in his memoirs: Every time we succeeded in a foreign land, it meant dollars brought to this country, and every time we failed, it was a loss to our nation and its workmen. One of our greatest helpers has been the State Department in Washington. Our ambassadors and ministers and consuls have aided to push our way into new markets to the utmost corners of the world.

The Baku oil congresses were beneficial not only for the major companies, but also for the overwhelming majority of small firms and private individuals in the oil business: by uniting on an issue, they could influence the bigger players. For the latter, the congresses provided an ideal platform to raise problems and advance their preferred solutions. They also provided an arena for discreet discussions with the central authorities. For example, rather than follow the risky and unpopular path of attracting western capital, the Nobel brothers preferred their own tried and tested methods, co-ordinated with and approved by the government.

Moreover, since the congresses brought together both large and small producers to co-ordinate their decisions, they helped to a certain extent to equalise all oil industrialists, regardless of size, giving privileges to the smaller producers. More than 150 small producers or companies took part in the oil congresses.

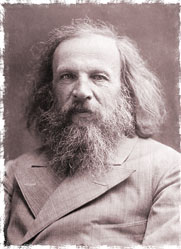

Russian chemist Dmitry Mendeleyev, famed for his periodic table, was a frequent attender. He was pleased with the depth of questions and the problems considered at the first congress, commenting that, ... the free assembly of figures in one industry in order to discuss their interests is major, welcome news not only for Baku, but for all of us. The open consideration of the questions and affairs of a free industry should be welcomed.

What did they discuss?

At the very first congress in 1884, the Baku oil industrialists raised the idea of “catching up with and overtaking America”. Rallying cries such as “we promise to fill the whole of Europe with kerosene”, “to be compared to American kerosene” and “our rights to compete with America” were heard at the congress. This was not empty boasting. Writing his memoirs, John D. Rockefeller gave his Baku competitors their due:

It is a common thing to hear people say that this company has crushed out its competitors. Only the uninformed could make such an assertion. It has and always has had, and always will have, hundreds of active competitors; it has lived only because it has managed its affairs well and economically and with great vigour. To speak of competition for a minute: Consider not only the able people who compete in refining oil, but all the competition in the various trades which make and sell by-products—a great variety of different businesses. And perhaps of even more importance is the competition in foreign lands. The Standard is always fighting to sell the American product against the oil produced from the great fields of Russia, which struggles for the trade of Europe, and the Burma oil, which largely affects the market in India.

Pipeline

Reading through material on the congresses, one can see a common thread running through all of them – the concern of the Baku oil industrialists to export their products. Item 12 on the agenda of the 1st Congress concerned “The best conditions for the export of kerosene and lubricant oils abroad, reduction in the cost of freight, goods storage at places of sale, the organisation of reception agents, delivery to buyers, etc.”.

The 6th Congress in 1890 considered “The consequences for our kerosene export of permission to admit tankers through the Suez Canal”, while the 9th Congress in 1897 debated the “Development of the sale of our kerosene in general, and bulk in particular, in the markets of the Far East”.

The 6th Congress was an emergency one, held to discuss the building of the kerosene pipeline. Russian oilman Viktor Ivanovich Ragozin said at the congress that: It is necessary to recognise as the best position only such that will transport everything that we produce, and this can be achieved only with sweeping changes in methods of transportation. That is why I consider this question closely connected with the question of tariffs and the kerosene pipeline.

Viktor Ragozin was a driving force in the Baku oil industry from 1883 to 1892. On the opening day of the 1st Congress of Oil Industrialists, 26 October 1884, Ragozin stressed the need for the geological exploration of oilfields. The next day, in a report on “The best conditions for the export of kerosene and lubricant oils abroad", he presented an extensive programme to develop the export of Russian (Baku) oil products, the main premise of which was a ban on the export of raw and semi-processed materials from the Russian Empire.

The problem of the prompt completion of the kerosene pipeline was raised again in a discussion on “measures to promote the distribution of oil products as replacements for foreign coal” at the 17th Congress, which was held from 8 December 1901 to 9 January 1902.

Mendeleyev was a strong supporter of the pipeline between the Caspian and Black seas. He was backed on this in 1872 by Baku oil industrialist Haji Zeynalabdin Taghiyev (1838-1924), who realised the importance of its construction for the economy of Azerbaijan. To counterbalance opponents of the pipeline, Taghiyev wrote to the governor of the Caucasus, Prince Alexander Mikhailovich Dondukov-Korsakov, in October 1886 about the urgent need to start construction of the pipeline. Furthermore, local entrepreneurs led by Aghabala Quliyev (1862-1924) created a joint-stock company in Baku on Taghiyev’s initiative to finance these works.

The Baku-Batumi kerosene pipeline was built between 1897 and 1907. The longest kerosene pipeline in the world, Baku-Batumi covered 829 versts (approximately 884 km) and belonged to the Transcaucasus Railway. N.L. Schukin, professor at the St Petersburg Institute of Technology, was the pipeline’s main designer. The pipeline was instrumental in enabling imperial Russia, and later the Soviet Union, to compete with the American petroleum industry.

Council and publications

The Council of the Congress had a counting house, secretariat and bank account. Funds came from the payment of a tax on each pood (approximately 16.3 kg) of extracted oil and on other industrial activity. The Council of the Congress also had a Special Statistical Bureau, whose duties included the collection, processing and promulgation of all data on the oil industry.

One of the first acts of the Congress Council in 1884 was to organise a network of specialist technical libraries for employees of the oil industry; the first library was set up for Council employees. By 1911, this library had more than 10,000 books in Russian, English and German, mainly on technical disciplines.

On 10 January 1899, the Congress started to publish the fortnightly newspaper Oil Business (Neftyanoye delo) in Baku; in 1908 the newspaper changed format to a magazine style. The magazine was renamed the Azerbaijan Oil Industry in May 1920 and is still published under this name today. The Congress Council also published two Reviews of the Baku Oil Industry, which provide an invaluable statistical database for researchers and historians.

Scholars of the history of the oil industry see the publications of the Congress Council, Oil Business and Reviews of the Baku Oil Industry as the model for the preparation and processing of oil statistics in many countries of the world.

Scientific progress

Analysis of the proceedings of the oil congresses shows that they discussed not only the business climate and conditions, but the latest discoveries in the new science of oil as well. Prominent scientists and industrialists, including Mendeleyev, Konon Lisenko, Ragozin, Taghiyev, Musa Naghiyev and Shamsi Asadullayev, frequently spoke at congresses.

The Baku oil congresses generated many ideas in the field of oil production and, alongside the Baku Branch of the Imperial Russian Technical Society, established in 1879, took a leading role in the technical education of oil and petroleum industrialists in Baku and the Russian Empire as a whole.

Detailed study of the proceedings of the congresses reveals a wealth of interesting ideas and proposals discussed: for example, the correct exploitation of oilfields, ways to improve the scientific and technical level of the oil industry in the Caucasus, the prevention of oil gushers, the best methods of storage of crude oil and the best way to export kerosene and lubricants.

Voting rights

The proceedings of the Congress Council accurately show who the leading oil industrialists were. Each respected oil company had a specific number of votes in the Congress Council. The number of votes was defined by the capacity of the company and its production volumes. According to the Council charter, “the extraction of between 100,000 and 500,000 poods of oil a year, the refining of between 100,000 and 200,000 poods of lighting and lubricant oils and the pumping of 1 to 2 million poods” entitled a member to one vote. A second and each subsequent vote required extraction of 2 million poods of oil, refining of 800,000 poods of lighting and lubricant oils and the pumping of 8 million poods per year accordingly. For example, at the 32nd congress Shamsi Asadullayev & Co. had ten votes, having joined the top ten oil companies of Baku as production from Asadullayev’s oilfields had reached 8 million poods a year. For comparison, the Branobel Company had 24 votes.

World leader

Those pledges at the 1st Baku Oil Congress – Let’s overtake America! – were fulfilled. In 1899-1901, Baku’s oil industry led the world in terms of the volume of oil extracted – 11.5 million tons per year; America was in second place with 9.1 million tons. In 1901 Russia, which included Baku at that time, produced 53% of the world’s oil.

High output was not without its own problems, though. The 16th Oil Congress considered serious charges to the oil exporters from smaller oil industrialists over the fall in kerosene prices. However, it was noted that the main cause for the sharp fall in prices for kerosene was the same as in America – the problem of uncontrolled output.

The oil congresses played an important role in the development of the oil industry in Baku. In 1920, after the establishment of Soviet power in Azerbaijan and the expropriation of oil industrialists, no more congresses were held and the congress council was liquidated.

Three of the Major Players in the Baku Oil Congresses

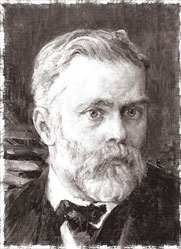

Viktor Ivanovich Ragozin

In 1884, Viktor Ragozin was appointed manager of the Baku branch of the newly established Sidor Shibayev & Co. Association. Thanks to major organisational changes and the introduction of new technology, the company soon became a leader in the Russian Empire in the production of lubricating oils. At the First All-Russia Exhibition on Lighting and Heating (1888) Ragozin exhibited a large collection of refined Baku oil products. After the exhibition he was awarded a diploma for "introducing for the first time the refining of lubricating oils and extremely useful work to establish their production in Russia and distribution in Russia and abroad". In 1889, at the Exposition Universelle in Paris the mineral oils of the Shibayev company, under Ragozin’s management, received a gold medal, while the company’s oilfield equipment was awarded a bronze medal. Ragozin was one of the most active industrialists at the first seven oil congresses in Baku.

Haji Zeynalabdin Taghiyev

Zeynalabdin Taghiyev was one of the most famous and respected oil magnates in Russia and the Muslim world. Born into a poor family, he began his working life as a bricklayer and finished as a millionaire businessman.

H.Z. Taghiyev & Co., founded in 1872, became a powerful oil company over the next 25 years, combining all branches of the oil industry, upstream and downstream. In 1887, his company produced 7 million poods of oil and 2 million poods of kerosene. He invested in all spheres of the national economy: oil production, building of trade centres, flourmills, fisheries and opened the first textile mill in Baku.

He is maybe even better known, however, as a philanthropist. He established the first high school for girls, the first drama theatre and the Shollar pipeline to bring fresh water to Baku. Taghiyev was elected honorary chaiman of the Muslim, Russian, Jewish and Armenian societies, which existed in the city at that time.

Emanuel Nobel

Emanuel Ludvig Nobel was born in St Petersburg in 1859, the first son of Ludvig and Mina Nobel, grandson of Immanuel Nobel and nephew of Albert and Robert. After his father Ludvig’s death in 1888, Emanuel, who was just 28, took over management of the Nobel Brothers Petroleum Production Company Ltd. in Baku. From a rocky start in 1888 as a young head of Branobel, Emanuel developed his skills as a manager to become a man of importance in Russian society, Nobel biographer Brita Asbrink wrote.

As head of the Branobel company, Emanuel Nobel was a driving, innovative force in the Baku oil congresses, just as he was in the oil industry as a whole. For example, he championed the manufacture and use of Rudolf Diesel’s new engines in Baku and across the Russian Empire.

On Emanuel’s initiative, Branobel set up schools, libraries and evening courses in technical education for their workers in Baku. Like Haji Zeynalabdin Taghiyev, Emanuel was a philanthropist, donating huge funds towards the establishment of the Institute of Experimental Medicine in the city.

About the author: Mir-Yusif Mir-Babayev is a doctor of chemistry and professor at Azerbaijan Technical University.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

John D. Rockefeller: Random Reminiscences of Men and Events, 1909, New York, Doubleday, Page & Company, available at projectgutenberg.org

Proceedings of the 1st Congress of Oil Industrialists in Baku, 26 October-8 November 1884, Baku, V. Neruchev Publishing House, 1885.

Proceedings of the 6th Congress of Oil Industrialists in Baku, 15-17 January 1890, Baku, Kaspiy newspaper publishing house, 1890.

Proceedings of the 11th ongress of Oil Industrialists in Baku, 21 April-2 May 1897, Baku, Aror Publishing House, 1897.