From The Incomplete Manuscript

by Kamal Abdulla

We publish below two extracts from The Incomplete Manuscript with the kind permission of the author and the publisher, the Strategic Book Publishing and Rights Co. In the first passage, the bard of the Oghuz, Dada Gorgud, is speaking.

Times were hard in Oghuz. An unknown tribe came and camped on a spur of Mount Qazilig, cutting off the waters of the River Buzlusel, one of the tributaries of the mountain River Sellama. They liked the place so much that they decided to settle there. No-one could understand their language or find out what they wanted. I was sent to them, “Tell them not to cut off our water. Whatever they want, we will give them,” the Oghuz noblemen told me, assembled in council around Gazan. “This is Bayindir Khan’s command. He said Gorgud should go. Meet their leaders, Dada. Whatever their terms may be, we give our consent.” The noblemen were openly sending me to my death.

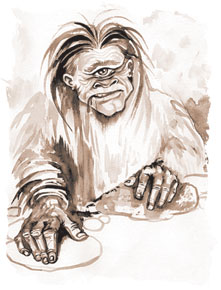

Their chief had one-eye and was weak and sickly. His eye gave me a terrible look as though he wanted to devour me alive. I stood rooted to the spot. Almighty God, bring me home safely to Oghuz, I said in my heart, seeking shelter in the Stone of Light, taking refuge in the skies and beseeching God.

“You must give us two men and one hundred sheep every day. Then we will unblock the river,” said a man who knew our language, kneeling near the one-eyed chief. The chief squeaked something inaudible, his voice matching his appearance. The same dragoman shouted his words to me, “Or else after cutting off your water, we will cut off your air. We will lay waste the Oghuz. That is our last word.”

“What do you need two men every day for?” I asked.

“We will eat the sheep, and our chief will eat the men’s hearts,” the dragoman said, looking lovingly at One-Eye.

What horror! I thought. They eat people! With that I bade leave to return.

“Go,” they said, “but if early tomorrow you do not do as we requested, our understanding will be rendered worthless. You will have only yourself to blame.”

I don’t know how I got back to Oghuz. I went to Gazan and recounted everything. The nobles were troubled and thought long and hard.

Further on in the The Incomplete Manuscript, Dada Gorgud recalls the day that he and Old Aruz found Aruz’s son Basat in the forest. Basat had just defeated the One-Eyed Ogre in mortal combat.

“I asked Basat, ‘Let’s talk, brave warrior. How did you vanquish One-Eye? What happened to his troops?”

“Don’t ask, Gorgud. One-Eye was ugly; he was not a sturdy warrior,” Basat had replied. “But there was sorcery. One-Eye was a sorcerer. Did you feel this?”

“Really? What form did this sorcery take?” I had asked, interested.

“I saw it in different forms. First, when I reached the bend in the river, I knew that we were being followed, but I gave no sign. Attackers came down from the crown of the hill, surrounded us and wanted to destroy us. ‘Stop!’ I said. ‘I have not come to fight; I have been sent as a present to One-Eye,’ Basat had explained. “They thought a good while before finally taking my warriors and me to the camp. ‘I have terms for One-Eye,’ I said. ‘Let me meet him.’ One-Eye came. He was feeble and weak, and he had a shrill voice. His hands were short, and a small wooden sword hung from his girdle, dragging along the ground. At his side was a dragoman, who translated what One-Eye said to me and vice versa.”

One-Eye had started to clap his hands excitedly and laugh. “Just look! A lovely lamb has come to us from Oghuz!” he had exclaimed. Then he studied Basat’s face and body carefully. After a few moments, he pointed at Basat’s chest and said, “My eye has seen this boy, and my heart loves him. Ask whatever you will of me. They told me you have something to say.”

“I...I would like to draw swords with you,” Basat had announced. “If you defeat me, you can eat me. If I defeat you, though, you will take your troops and army and leave these parts, never to return!”

“You against me? Don’t you know me? Haven’t you felt my strength?” One-Eye had asked. He then roared with laughter. His attendants had laughed, too.

“If you want, I’ll prove to you that your strength is no match for mine,” Basat had said confidently.

“Many of your people have come and perished here. I approve of your courage. Didn’t I say that when my eye saw you, my heart loved you? I’ll do battle with you, but I have a condition, too. If I beat you, I won’t kill you. I’ll make you my servant. You’ll be my servant. What do you say?” One-Eye had asked.

Basat had nodded. “I say yes,” he then replied.

“Prepare the battlegrounds!” One-Eye announced to his attendants.

The battlegrounds were inside their camp. One-Eye’s attendants took Basat and his men there and drew a line around them in the sand. One-Eye had then pointed directly at Basat. “Strip this warrior! Let him be naked as the day he was born,” he ordered. Seconds later, his attendants had stripped Basat naked. Then they gave him a shepherd’s cloak and his sword.

Next, One-Eye entered the battlegrounds. Shouts of “Live long!” rose into the air in unison. Basat had thought to himself, What strength does this weakling have that such big troops obey his every word? At the same time, he began asking God for help, as he, too, entered the battlegrounds. Once inside, he had immediately raised his sword and wanted to attack One-Eye, but his arms and legs froze.

One-Eye hadn’t even been looking at him. He was strolling to and fro on the battleground, chatting to the onlookers, laughing, and making them laugh. Almighty God, what’s wrong with me? Why have I frozen? Why is my sword still? Why does this small man not even look at me? Basat had wondered, trying not to panic.

Suddenly, he saw One-Eye right in front of him. He almost thrust his small wooden sword into Basat’s eyes. In that moment, Basat’s senses had returned. He swung into action and leaped aside. With that, One-Eye playfully started to stroll about the battlegrounds again. Then Basat’s eyes settled on a pair of eyes at the top of the camp. The two eyes were watching him from the charnel house that the newcomers had set up just below the brow of the hill. The eyes bored into Basat. At first, he did not know them, but then he did. It was his mother, Gogan, the lioness. She had found him!

“Strength came to me, and I wanted to attack One-Eye. However, he had suddenly disappeared,” Basat had explained. “Father, who did I see instead?”

“Who?” Old Aruz and I had asked together.

Basat had looked at Old Aruz incredulously. “Father, I saw you!” he had exclaimed. “It was you. You were standing before me! One-Eye had turned into you in the blink of an eye. I had trouble holding back my sword and nearly killed you.”

At that moment, the battlegrounds crowd had burst out laughing again. Basat had been both confused and furious. “What are you doing here, Father?” he had asked.

“My son, I came to help you...” Old Aruz had replied in One-Eye’s shrill voice.

But Basat had realised that his father was not standing before him. One-Eye had cast a spell on him. He began to walk around the circle, fixing his eyes on One-Eye. Suddenly, One-Eye spun around and was either pulled into the earth or flew into the sky; he was no longer there. His soldiers had been beating their swords and lances against their shields, shouting in strange voices. Basat had quickly become deaf from the noise and yelling.

Yet again, Basat felt that two eyes were boring into him. This time, though, they were sending him a sign. Don’t hurry, a thought entered his mind. Don’t hurry at all. If he is to be killed, he will be killed only with his short sword. Wait for the right moment.

Suddenly, Basat heard breathing behind him. He spun around and saw the Khan’s daughter, Lady Burla, standing there. Instinctively, he courteously bowed his head and asked, “Lady Burla, how did you get here? The battlegrounds are no place for a lady! Come over here, lest you be hurt or hit. I’ll look for One-Eye. Have you seen him?”

As soon as Basat had spoken, the soldiers roared with laughter again. Lady Burla skipped around the circle, belly dancing for some of the soldiers. Almighty God, why is Lady Burla doing this? Basat had wondered, completely shocked.

That’s when he suddenly heard One-Eye’s shrill voice coming from Lady Burla’s mouth. “Come to me, boy! When you cast your eyes upon me, you loved me with all your heart. I have given my soul to you. What’s wrong? Make haste! Seek my hand from my father. Send an envoy to my father, the Khan, or I shall enter the bed of another and make you burn with jealousy. Come, quench my desire and I shall quench yours...”

One-Eye continued, still disguised as Lady Burla. “Basat, Basat, bravest of the brave, apple of my eye, love of my heart, what are you waiting for? Go to my father, the Khan, and ask for my hand. Make me your wife. I’ll be the mistress of your tent; I’ll be the woman of your bed; I’ll kiss you thrice and bite once; I’ll bite you thrice and kiss you once. Come to me, boy! What’s wrong with you?”

When One-Eye spoke as Lady Burla, Basat had immediately lost his head. He shouted angrily and fell upon One-Eye, trying to seize him, but he couldn’t ever catch him. Seconds later, One-Eye changed back into himself. Again, he started to pace the battlegrounds like a victor.

Words then entered Basat’s mind again from the charnel house. Don’t hurry! Don’t hurry at all. Let him use up all his strength. Let him finish it. Let the magic leave him; only then, should you pounce. But now, don’t hurry. Listen to me. Look into my eyes. When the time comes, I shall give you the order to strike... With only a look, Gogan, the lioness, had sent an important message to Basat, heartening him.

When Basat turned his attention to One-Eye again, he had transformed into me. I was sitting cross-legged on the ground, playing something that looked like a saz; however, it didn’t make a sound. The troops didn’t like what they saw. They yelled and clamored. One-Eye gave them a sign with his hand to wait. Then, without warning, he jumped up into the air, turned a somersault, and became an ugly, monstrous, naked Cyclops.

As soon as he landed on the ground, however, the single eye fell to the earth and stayed there. One-Eye immediately got to his knees and began feeling the ground around him. Meanwhile, the troops continued their clamor. One-Eye’s beloved short sword had fallen when he somersaulted. That’s when Gogan, the lioness, had sent Basat the sign: Go, boy, your time has come! Pick up the sword. Don’t let go of it! With that, Basat quickly threw himself upon the sword and took it in his grasp. It was a clumsy sword made of wood.

“One-Eye had shuffled his enormous bulk, back and forth, over the battlegrounds. His shrill voice could scarcely be heard and this time no sound came from the troops. When he turned the somersault in the air, One-Eye had finally let go of his magic,” Basat had explained. “He wanted to get it back, but no matter how he tried, he could not do so. I began to walk all around him, keeping his sword in my hand. I waited for a sign from Gogan, the lioness: ‘The sign finally came: Run, boy, the time has come! Cut off his wicked head with the wooden sword!’”

“Then what happened?” Old Aruz had asked, completely mesmerized by his son’s account.

“I ran, Father, and struck One-Eye’s neck with the sword. It went in like a knife through butter and came out the other side. His head lay on one side, his carcass on another. The troops screamed and then fell silent,” Basat had replied, remembering the dramatic events. “I grabbed One-Eye’s head, raised it to the sky, and strode around the battlegrounds. I had avenged my brother, Giyan Seljuk! But, Father, when I raised my head, I saw that –”

“You saw what, my son?” Old Aruz had whispered, his blood freezing in his veins. I had turned white.

Basat continued. “Father, don’t be afraid at all. I saw that One-Eye’s troops were no longer there. The battlegrounds were suddenly deserted – their camp, their tents; you can see for yourself,” he had said quietly. “I don’t know whether they were ever really there or not.”

We had looked all around us. Indeed there was no trace of One-Eye or his troops. I was at a loss for words. “What happened to One-Eye’s body, Basat?” I had asked, trying to make sense of everything.

“Gogan, the lioness, took it,” Basat had replied. “But this is his sword.” He had pointed at a small wooden sword that was lying on the ground. We looked at the sword for a few moments, and as we continued to look at it, the sword suddenly grew smaller. A few moments later, we couldn’t see it any more; the sword had completely disappeared.

Basat looked at Old Aruz. “What shall we do now, Father?” he then asked, looking tired. “Shall we go home? May Giyan Seljuk’s spirit be glad...”

Old Aruz nodded and placed his arm around his son’s shoulders. “Let’s go, my son, my Lion,” he had replied proudly. “We’ll celebrate this day.”

Old Aruz let out a long sigh, remembering how proud he had been of his son in that moment. Then he looked at Bayindir Khan. “The warriors and servants had finished clearing the river. The River Sellama raced and roared again down towards Oghuz. The river’s water reached Oghuz before us, my Khan,” he said, ending his speech. “When we arrived in Oghuz, everyone – young and old, women and children – had gathered to gaze joyfully at the water.”

Illustrations by Evelina Aliyeva

Translation from Azerbaijani by Anne Thompson-Ahmadova