Józef Gosławski

Speaking about the personalities, let us stop for a moment on Józef Gosławski, better known under his Russified name Yosif Vikentevich Goslavski. His first project in Baku was the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral, which stood on the spot where the Bulbul Music School now stands. When he was offered the job, he had just graduated from the Institute of Civil Engineering in St Petersburg and had no chance of making any kind of satisfying career in Russian-governed Poland. Moreover, what seemed to be the most serious obstacle to his professional future, he had no mighty backer to sponsor his first projects on his own. So it seemed to be a marvellous opportunity to work with such a well-known, successful architect as Robert Marfeld on a project that enjoyed the interest of the emperor, Tsar Alexander III, himself.But there were some shadows, too. Gosławski was well aware that Marfeld, still a young man, enjoying the celebrity life in St Petersburg, with plenty of on-going projects in different locations in European Russia, would not go even once to provincial, mud-and-oil covered Baku, so all the burden of construction work would be on his, Gosławski’s shoulders. If the church pleased the tsar, all the fame would go to Marfeld, if not – all the blame would go to Gosławski, the Pole, the Catholic, the inexperienced architect, whose career would be ruined before it even started. For sure, he knew about the issues on the ground: the long-lasting dispute between the Russian authorities of Baku and the local Muslim community, since the cathedral was to be built on the territory of a long-disused cemetery; no financing had been secured, either, and he found it hard to rid himself of his anxiety at the high expectations.

The residence of oil baron Murtuza Mukhtarov, designed by Josif Płoszko. The building is now known as the “Palace of Happiness” or, offi cially, State Registry Offi ce No.1.

The residence of oil baron Murtuza Mukhtarov, designed by Josif Płoszko. The building is now known as the “Palace of Happiness” or, offi cially, State Registry Offi ce No.1.

Also, he had a young wife expecting their first child; do you think she was keen to change their comfortable, cosy urban life for what she saw as some wilderness? Younger people nowadays might not believe me, but she had no Skype to talk to her parents when she felt lonely, no Internet shopping. In many respects it was not the best time to plan such adventures.

Nevertheless, Gosławski came to Baku in 1891, started his job and grappled with all the difficulties he had been aware of and many more besides. Marfeld sent only very general plans, indicating that the tsar expected the new church to be the most prominent monument in all Baku, both now and in the future, and the centre of Orthodox religious life throughout the Caucasus. The models to be followed were also from the top drawer – the cathedrals of Saint Basil and Christ the Saviour in Moscow. The domes had all to be covered with pure gold, while gold and silver were to be poured into the moulds to make the bells ring smoothly. The generosity of the emperor, contrary to his expectations, had its limits and Gosławski was forced to ask for public support – it is said that without too much trouble he collected 200,000 roubles, a really enormous amount of money (the average monthly salary in the imperial capital St Petersburg was then around 30-40 roubles), and the most generous donors were the Muslim and Jewish communities of Baku.

I was puzzled by the ease with which Gosławski, a foreigner and Mr Nobody, was entrusted with such a large sum. He could have taken all this money and fled to neighbouring Persia with his wife and young child, but he did not. Baku then was a small city and everybody would have soon noticed if some of the gold that should have been poured into the bell casts made its way into the architect’s pocket; actually, although the town was full of gossips, there were no rumours of Gosławski taking anything! He showed his utmost honesty and fate rewarded him with the best gift possible – a sponsor who trusted him and understood his vision. Zeynalabdin Taghiyev, his super-rich patron, secured for the newly appointed chief architect of Baku (Gosławski took up this new challenge in 1892, at the young age of 27!) such funding for his projects that the sky was the limit. The young Pole made the most of this opportunity. Of course, in those days there were no large architects’ studios, where a bunch of younger architects worked under the guidance of the leading, famous name architect. Gosławski had to do all his projects from A to Z by himself. As the boss, he was most probably a nightmare – he wanted his projects to be executed to the letter and checked even the most minor, almost invisible, fragments and details.

He seems to have been so committed to his job that his family life suffered, as well as his health. We cannot read much from the photographs taken in many European cities where Josif travelled with his family. As was the custom in those days, everyone stood ramrod straight, without even a hint of a smile, but at least the photos show that he took some vacations with his expanding family… In 1904, when he was in the final stages of tuberculosis, he was abandoned by his wife, who went to Poland with two of their children, leaving behind the youngest, Łucja. Maybe there was a conflict between two strong personalities – Josif’s wife on one side, and his sister Michalina, on the other? Maybe he wanted to spare his family observing his last moments? We know that they came back to Baku after Gosławski’s death; there are photos of their reunited family dated 1906, but they soon split again. The widow with two of the three children went to Poland, while Michalina with her adopted daughter and Łucja stayed in Baku. It is Michalina who took care of all Gosławski’s belongings, papers, books, even his collection of lighters (he had more than 300!). Łucja left Baku in the 30s and moved to Leningrad, taking with her many of her father’s papers; she seemed to be a ‘daddy’s girl’ and the most attached to him; she never married and had no children. Almost all of Gosławski’s archives were lost after Łucja’s tragic death during the World War II siege of Leningrad.

Josif Płoszko

The other name, which you can hear in Baku as often as Gosławski’s, is that of one more Josif, Josif Płoszko. We know this man mostly through his buildings, as we know nothing of his life when he stood up from the drawing board and went home. He was married to a Sabina Vladislavovna; did they have children? The only surviving family picture is from 1903 (when Płoszko was 36); Sabina looks very cheerful, while Josif is of course ramrod straight, with a serious, far-reaching expression. He made his way from St Petersburg to Baku, with Gosławski’s invitation in his hand. He was almost immediately asked by one of the local billionaires, Agha Musa Naghiyev, to erect a building as a memorial to his late son Ismayil. Płoszko’s sponsor had a less developed taste than Taghiyev and wanted the young architect to implement some ideas that had a touch of the nouveau-riche about them, such as quasi-philosophical sentences inscribed in gold high on the external walls of the building. Płoszko skilfully implemented this as well as other wishes and designed a palazzo in Venetian style, which was not only comparable with the nearby Duma, one of Gosławski’s works, but overwhelmed it through its clarity, balance and richness of detail. How did he feel a few years later, when this very building, immortalizing Ismayil’s and his own name, was devastated and burnt by hordes of Bolsheviks?Płoszko erected some buildings serving religious communities. He designed the only Catholic church in the city, known as “the Polish church” – not only because the majority of the parishioners were local Poles, but also for the style it was built in – the Polish Gothic, less pompous and more sophisticated than the Western one. He was also in charge of the rebuilding of the main mosque in Shamakhi. This was a challenge – the historic 8th-century mosque had been reconstructed many times during its long history and had been almost totally ruined by the disastrous earthquake in 1902. Płoszko was eager to accomplish this project, but at the first stage the task was entrusted to his close friend and partner, Zivar Bey Ahmadbeyov, the most famous Azerbaijani architect at that time who was, by the way, born in Shamakhi. Ahmadbeyov opted to faithfully preserve the initial features of the building, which did not please the funding committee, so Płoszko was asked to present his sketches. He wanted a completely new structure, built according to the 15th-century Shirvan school, with its all most prominent features. I do not think that he was pleased with the result – due to financial difficulties some of the most distinguished elements had to be omitted, such as the central dome, two of four side minarets, ornamented stairs etc.

Unfortunately, those two buildings did not survive to our times – the mosque was burnt down during the civil war in 1918 and not rebuilt until 2009, when it was reconstructed according to initial plans left by Płoszko. Even sadder was the fate of the Polish church – in 1936, at the peak of the antireligious campaign, it was demolished and on this spot the Soviet government built a house of culture, bearing the name of another Pole – one, we are at all not proud of – Feliks Dzierżyński (more commonly known in English as Felix Dzerzhinsky).

Fortunately perhaps, Płoszko did not survive to see these tragic events – he died in 1931 in Paris. Before his death, he spent some years in Warsaw, where he could not adapt to the new reality. When he had left the homeland, Poland did not exist as a state; Warsaw was a very Russified, provincial city and study in St Petersburg or Moscow offered the best prospect of a promising career. In the 1920s, Poland was a developing European democracy, oriented towards the West, also in such fields as the arts, architecture and science, whereas due to the political disturbances Azerbaijan had drifted away from its European path of development and found itself under the destructive wings of Bolshevism. In Baku Płoszko was the most prominent architect, with undeniable achievements, which were virtually unknown in Poland. After his return from Baku he became just another carrot in the carrot field, as we say in Polish.

Visionary

When I compare those two architects, I have the feeling that Gosławski had a somehow broader perspective, that he was a man of vision. His plan was not only to have a building or two in the centre of the city, he wanted to create a new Baku, like a nucleus, a self-restructuring fractal that would multiply in a complete fusion of different Western European styles with highly visible Eastern elements of Azerbaijani origin. Płoszko was closer to the needs of everyday life; the vast majority of his surviving work was residential buildings or hotels. His houses still serve the people of Baku – on Persidskaya St (now Mukhtarov St), Shamakhinskaya (Jabbarli St) and Politseyskaya (Yusif Mammadaliyev St). The latter was built as a city residence for the Polish Rylski family, who were part of Baku high society. It enjoyed its heyday during the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic (ADR) in 1919-20, when the Rylskis offered the premises to the newly established Polish diplomatic representation. Unfortunately, the Polish diplomats had no chance to make themselves comfortable in the embassy, which had been fully furnished and was awaiting their arrival – they came to Baku by train on 23 April 1920, just on the eve of the Bolshevik rebellion. Immediately after the fall of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic, the diplomats were arrested. The Catholic Church, designed in the Polish Gothic style by Josif Płoszko, stood near the junction of modern-day Rashid Behbudov and Zarifa Aliyeva streets. It was demolished in 1936. Photo: Azerbaijan State Archive

The Catholic Church, designed in the Polish Gothic style by Josif Płoszko, stood near the junction of modern-day Rashid Behbudov and Zarifa Aliyeva streets. It was demolished in 1936. Photo: Azerbaijan State Archive

Kazimierz Skórewicz

There is a third name that we should not forget when we talk about Polish traces in Baku architecture – Kazimierz Skórewicz. I have the impression that Skórewicz is somehow in the shadow of his two famous colleagues, which is very unfair. He was the chief architect of Baku for a short time, a little longer than a year, but his work before this for the city was at least as important as the work of Płoszko or Gosławski. He was a schoolmate of Józef Gosławski, who invited him to Azerbaijan one year after Skórewicz graduated from his alma mater in St Petersburg. The young Pole was impressed by the extravagance and lightness of the local architecture: his buildings designed for Baku are full of limestone, arches and domes, and have not become dated over time. Who would assume that the recently renovated building of a modern supermarket on Rasulzade St is more than a century old? Skórewicz designed it for Zeynalabdin Taghiyev in 1896, using unusual elements for the time such as a wide glass-ceiling and visible details from reinforced concrete (this was the first time reinforced concrete was used in Azerbaijan). He liked his buildings to resemble the Roman god Janus – many of them face three streets, and every façade is somehow different, even bearing elements of different styles. The house of oil baron and philanthropist Haji Zeynalabdin Taghiyev, designed by Józef Gosławski. It is now the National History Museum of Azerbaijan.

The house of oil baron and philanthropist Haji Zeynalabdin Taghiyev, designed by Józef Gosławski. It is now the National History Museum of Azerbaijan.

During his Baku years he started the culmination of his life work. As one of the leading architects of the city, he committed himself to planning buildings for state and private use, but he also produced fundamental research on the Western Slavs’ architecture and developed a project that soon became Baku’s visiting card – the seafront Boulevard. In 1902 Skórewicz was asked “to do something on the seashore”. He resolved to use the “green architecture” concept, so popular in European cities located on the coast or along a river bank. First, he organised a small, picturesque park, more like a private flower garden than a public space, but this pleased the City Council and he was tasked with placing the green public park the length of the seafront in central Baku.

From my personal point of view, his most outstanding achievement was City Hall, which was started by Gosławski a few years before his death. When Gosławski died, the external structure was basically ready, but there was still much to be done before work could begin on the interiors. Most probably, nobody at that time knew that Skórewicz had prepared an alternative proposal for the exterior and interior of the building, but it was Gosławski’s idea that had been accepted. After his friend died, Skórewicz was asked to finish the job. It was the ideal opportunity to put aside the plans of the late chief architect and follow his own ideas – but Skórewicz remained faithful to the memory of his former superior and close friend, seeing through Gosławski’s project.

Legend has it that Skórewicz was involved in clandestine activities during the 1905 revolution, which was the reason he left Baku for Poland the following year. I very much doubt this, as he was too busy with all his tasks, his family and various projects. Moreover, in such an exposed post as his, it would have been virtually impossible to co-operate with rebellious workers and professional revolutionaries without being discovered. As a Pole his position was even more vulnerable, since we were notorious for uprisings in occupied Poland and our eagerness to share revolutionary sentiments with other oppressed nations. The last argument against the revolutionary theory is that when Skórewicz returned to Russian-occupied Poland, he remained active and no action was taken against him. Most probably, after the political situation in the Russian empire started to improve, he grasped the opportunity to go back home.

Skórewicz’s work won open competitions, bringing him increasing popularity, then fame and financial independence. After the Russians left Warsaw in 1916, Skórewicz established the chair of architecture at Warsaw Technical University and became its first professor. He worked for 10 years on the material history of the Royal Castle; in 1939, when the castle was burnt by the German occupiers, it was this 73-year-old professor who tried to save all the most precious pieces of art from total destruction. His profound knowledge was priceless after World War II, when the authorities decided to rebuild the castle as a symbol of the unbreakable chain of Polish history. During the war Kazimierz Skórewicz lost two sons – the younger was shot dead in a mass execution at the beginning of the war, while the elder died in Auschwitz. His only daughter was his support and help in his last years, when he was writing a monumental History of Polish Architecture. He died in 1950, after completing this tome.

Other Poles

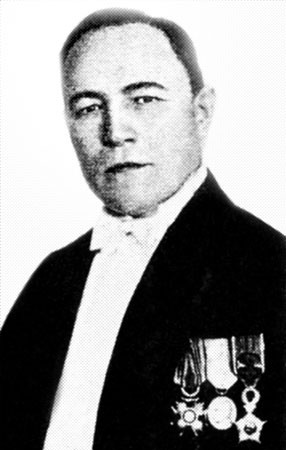

This short essay has focused on three figures, the most prominent and famous of the Azerbaijani Poles. We have been able to lift a corner of the official curtain and take a look at their “human” face. But we could do this only because they lived here for many years, were very visible through their official positions and work and left some marvellous buildings for future generations to admire. There are dozens of other Poles, though, who served this country in different times, different places and in many different ways. For example, Leonid Młokosiewicz, son of Ludwik Młokosiewicz, who spent his entire life in the Zaqatala region. Leonid was deeply respected among all the local peoples for his culture, scientific achievements and profound knowledge of the region gleaned during his protracted journeys over the slopes of the Southern Caucasus. Leonid created the Zaqatala Regional Museum and was its first director – unfortunately, he perished in 1937 during Stalin’s purges… Olgierd Najman Mirza Kryczyński, deputy minister of justice in the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic government

Olgierd Najman Mirza Kryczyński, deputy minister of justice in the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic government

Olgierd Najman Mirza Kryczyński (his family name shows his Tatar roots) served as the deputy minister of justice in the ADR government and was Azerbaijan’s representative to the Caucasus Conference in 1920 in Tbilisi. After the fall of the republic he fled to Poland and worked as the country’s prosecutor general. One of his relatives, Leon Kryczyński, was the head of the Azerbaijani government’s chancellery in 1919-20; he escaped with his cousin to Poland and worked in Vilnius (then in Poland) as a lawyer.

Aleksander Makowielski made his way in the opposite direction – born in Grodno, he studied philosophy at the best universities of Russia and Germany; after he had written fundamental research on pre-Socratic Greek philosophy, he was invited in 1920 by the new government in Baku to teach at the newly established university (now Baku State University). He was a founder of the Azerbaijani school of philosophy; by the way, his daughter, Olga Jurzanina-Makowielska, is one of the leaders of the Polish community in Baku. In the case of people such as Makowielski it is easier to collect information, since there are still people around who worked with them, their relatives who cherish their memories and clear documents from their lives.

Another example is Wanda Orłowska, who for many, many years was director of the library in the Azerbaijan Academy of Sciences – she died a decade ago, but her great personality still lives in the memories of her colleagues and friends.

But what about the hundreds of ordinary people who spent their lives in Baku or Ganja? I am very interested in them, in how they lived. How did they spend working days and holidays? Where did they go in August, when the weather in Baku is unbearable? Before the church was built, where did they go on Sundays for mass? The diligent researcher can catch glimpses in the archives – a newspaper report of a fire in the pharmacy of a certain Zieliński; or an advertisement of a lawyer with the Polish-sounding name Nowakowski. Doctors, engineers, teachers, oil workers, soldiers… Ultimately, this is the fate of us all, but I long for this unknown, forgotten Polish Baku, which perished in the waters and fires of the 20th century, leaving behind just some monuments and scarce memories.

About the author: The former ambassador to Azerbaijan (2010-2014), Michał Łabenda likes research on the history and culture of the East, talking to people who are good specialists in something and learning languages. He is happy to have found a job combining all those three elements. He is currently back in Warsaw.