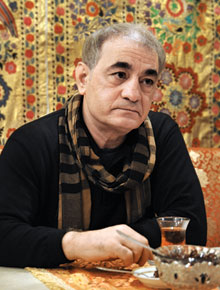

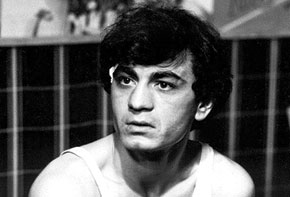

Fakhraddin Manafov is one of Azerbaijan’s most recognisable actors, the star of dozens of films and stage plays. He is also a familiar face outside the country, as he has acted in many films made by foreign directors. Our interview was rather unusual; it was more like a conversation with a man whose eyes betrayed the depth of his soul, a keen soul that has suffered much. Or maybe he gives this impression because of the characteristic energy of all the characters he has created on stage and screen. Whether it is the image of fearless Timur battling adversity in the film Goodbye, Green of Summer, or his opposite, the spineless Zaur, oppressed by social stereotypes in Tahmina. It was this role that rocketed the actor to fame. They are all very different parts but equally loved. His brilliant performance as Ibrahim Khalil Khan in the film Destiny of a Sovereign marked a new departure in his work. The plot of this historic film concerned his homeland, Karabakh, so he approached filming with both greater trepidation and enthusiasm than usual.

Comparisons are made with American actor Robert De Niro, but once seen there is no forgetting Fakhraddin Manafov. Perhaps it was fate that the actor, who has been awarded the title People's Artist of Azerbaijan and the Zirva (Peak) prize, was born on 2 August, National Cinema Day in Azerbaijan. Though with hindsight he may have seemed destined for the film-set, he started out in life as a footballer. How did a budding sportsman suddenly change direction? This is where we started our conversation, but as a former footballer, Fakhraddin muellim decided to take the initiative and kick off:

Why are you in journalism? How did you get into it?

I think I was just sucked into the swamp.

You are right about the swamp. In the same way I was drowned in the arts. One minute I was a footballer, committed to sport, then I got carried away by acting and was sucked deep into the swamp. As I fell in love with the arts, I realised that I could express myself better here than on the pitch.

What is self-expression to you?

It’s challenge. At any age, people want to express themselves. You can certainly do it on the pitch, in the ring or even in through Zen, just stop talking, or adopt the sirsasana pose, close your eyes and fly off into nirvana and express yourself in that way. For me though, art is still the only form of self-expression. Mankind has invented nothing stronger than the arts for this purpose.

Any kind of art is said to require sacrifice. Do you agree and, if so, what have you sacrificed?

To be honest, I do not accept the concept of sacrifice in art. What does it mean “to sacrifice yourself to your art”? If I took this path with genuine desire and love, then what I give up should not be considered a sacrifice, because this word alone is already undermining my true attitude towards art. I get great pleasure from what I do. So what kind of sacrifice can we talk about?

Let's say giving up the chance to be a famous footballer?

I can play football even now, if my health is up to it. But seriously, I do not accept the idea of sacrifice in art. I live with art, it’s woven into my fabric. I love my profession.

Your film roles are mostly dramatic. One of your earliest and best-known parts is Zaur in the film Tahmina. What aspects of Zaur do you share and what aspects are not you at all?

The late Azerbaijani director Rasim Ojagov, the 80th anniversary of whose birth was celebrated last year, always told me: do what you want to do, play how you want to play, but always adhere to the concept that was set. Although I love to improvise, at the same time I have always remained within the concept given by a director. I just try professionally to get the feel of my role, including the part of Zaur, who is not like me at all. Yes, he isn’t like me, since Zaur and I have absolutely nothing in common. We are strangers to each other. For instance, I fell in love with my wife and remain true to this love. I am a free man. If I had fallen in love with Tahmina in this film, I would never have allowed myself to treat her the way Zaur did. I would not care about public opinion, of which he was so afraid. And it wasn’t just Zaur that was afraid but his parents and friends too. In fact, Zaur was a coward. If I were him, I would quietly take Tahmina’s hand and boldly say to her parents: You do accept me as I am, don’t you? You don’t? Goodbye.

/>

If your parents had not accepted you, would you have left society?

I would have, but not Zaur. He was a victim of society, whereas Tahmina remained free. If he had been a little freer in his soul, I am sure that he would have acted differently.

Well, it’s probably a question of freedom of choice, isn’t it? Maybe Zaur sacrificed his love for a woman and chose love for his parents? After all, respect and obedience to parents are the foundation of our families...

Then love for parents has to be expressed in blind obedience, is that it? I strongly disagree. Believe me, love is expressed quite differently... I remember when the first film in which I appeared was released, my parents were just proud of me, especially my Dad, although our views on life were very different. I remember how proudly he walked by all the billboards advertising the film and told everybody what kind of a son he had. I learned about this from my uncle, my father never told me about it. In his heart he was worried about my creative decisions. He is tremendously creative and has a very beautiful operatic voice. However, he failed to realise his creative potential. My father was already 40 when his operatic talent was discovered and he was told that it was too late to train his voice. Evidently, his son realising his creative potential gave him a sense of joy and pride, notwithstanding that he had failed to do it himself. So it would be a mistake to assume that Zaur left Tahmina only because he loved his parents. Simply, people must choose in life what they want and not what is dictated and imposed on them by society.

Have you played yourself in any of your roles?

If I approach your question from the perspective of a professional actor, I can say that in all my roles I have played myself. I won’t be revealing a big secret if I say that every human being has both good and bad qualities – good and ill, wise and foolish, noble and ignoble, etc. If we properly analyse ourselves and our actions, we can find in ourselves that self-same Zaur (Tahmina) and Ibrahim Khalil Khan (Destiny of a Sovereign), and Yousif (Temple of Air) and Ziyad Khan (Mahmoud and Maryam). They all exist in our hearts, we just have to find them. Everyone has a multitude of faces, characters, features. Our profession is interesting, tremendous since an actor can easily transform himself.

If I had the chance of being born again, then without a doubt I would choose one of these three professions: I would be an actor again, a writer or a musician because a person’s internal strength lies in art.

Is there a part that you have not played yet but would like to play?

As a rule, 90% of male actors would like to play Shakespeare's characters. Who would I like to play? I would like to play in a film where the camera from the outset and without stopping is directed on me. I do not know how long it would last, maybe five minutes or ten, or maybe three hours but it would all be filmed without sound.

Who would you most like to direct you in this film? Which Azerbaijani directors do you most enjoy working with?

My favourite director is our great Rasim Ojagov. Sadly, we have lost him. With him I would have worked non-stop. Among the current directors I would single out Ayaz Salayev, a very talented and intelligent man. Among the younger generation, I would choose Punhan, who has the awesome flair and vision of a director. He is a remarkable character. We have ideas which I hope will soon come to fruition.

Who are your favourite foreign directors?

I love the films of Tarantino, Spielberg, Lars von Trier.

Which films do you think are best for influencing the next generation?

I will not name them, I can only say films by those directors who have their own vision and own pain. And you know, a generation grows up all the same. You probably remember the tale of the papyrus that is thousands of years old, but has a text complaining about unruly youth. The conflict of generations has always existed and will always exist. And I assure you that no director, they will forgive me if I'm wrong, thinks about the role of his work in shaping the generations. A director shoots a film, because this is how he wants to express himself, his feelings. Like any artist, he does it for himself. And what we, the people, take from his films is another question. A generation will always find its director, writer, actor...

Let's talk about Azerbaijani cinema. Lately it seems to have revived, new films are made and new directors appear. Can we talk about progress in Azerbaijani cinema?

Unfortunately, we are not a cinema empire. After the collapse of the Soviet system, our cinema appeared to be on the edge of the abyss; we were not able to respond quickly to the challenges or to organise film schools. Today, the sole university of culture and art in the country is actually a conveyor belt for graduates who will work anywhere but in the arts, and especially not in film-making. We have lost time and created a void that cannot now be filled because of the lack of professional staff. Certainly, there are interesting, talented directors and actors among the younger generation, but they are too few and do not have enough opportunity to realise their potential.

It’s elementary that making a film does not require only funds. On the contrary, raising the funding is not so difficult. It’s getting hold of other resources such as professional cameramen, lighting specialists, costume designers, set designers, make-up artists and so on that is much harder. And this is only a small part of what a film requires.

You know, there is no nation that doesn’t have talented people, especially not ours. We are very rich in talent, but we need to be able to rise to the challenges. For example, when the Great Patriotic War [World War II- Ed.] started, all the film studios, including the Gorky, Dovzhenko and Mosfilm studios were moved to Central Asia, especially to Uzbekistan, as the war had not reached there yet. Incidentally, in the mid-80s I was in a film by Elyer Ishmukhamedov, the talented Uzbek film director, called Goodbye, Green of Summer. This film gave the Uzbek film-school a huge impetus to develop and, even today, after many years, a number of well-known film-makers of the former Soviet Union are graduates of this school. Elyer Ishmukhamedov today works at Mosfilm. The gorgeous cinematographer Dilshat Fatkhulin, winner of numerous awards, was invited to Azerbaijan to work on Destiny of a Sovereign, while well-known director Zinoviy Roizman shot the film Drongo in Baku. Both of them are from Tashkent.

You mentioned the Soviet school of cinema. What is your attitude towards Andrey Tarkovsky?

He makes me cry ... You know, in my time, I often acted at the Mosfilm studio in Moscow, and in the same building, the two lower floors of which are rented by the hotel Mosfilm, right in front of the entrance hangs a plaque with the inscription “Tarkovsky lived here”. Walking past I would always pause at this plaque ... Unfortunately, I never met him, but I have read a lot about him and loved watching all his films. I must have seen Stalker 27 times. Tarkovsky and Spielberg are two directors, whom I would compare with each other. Their only difference is that Spielberg was able to escape from reality, but Tarkovsky was not. For me, Tarkovsky is as inaccessible as outer space, as a thought.

Actually, Tarkovsky had so many interesting thoughts. He once said that life loses meaning if we know all about it. Ignorance is noble, knowledge is vulgar, he said. Are there things in your life that you would like to leave incomprehensible in line with Tarkovsky’s understanding?

Yes, I would like to leave certain things incomprehensible. Frankly, when I see before me an educated, wise, well-read, intelligent man, for some reason I feel ashamed that this man can now suddenly sense the emptiness in my life path and how I wish that were not the case. I recently read a saying about truth and loved it. Truth is an illusion and to get rid of one truth you must come up with another. You can get rid of it but you cannot change it. I just want to understand one thing: why we are born and why we die.

What should a person be like in the understanding of Fakhraddin Manafov? Well, let's start with men...

Of course, I can list a set of parameters that must be met by a man, but I had better limit it to one – he just has to be right, and that's it.

Well, what about a woman? What is your ideal woman like?

She should be right too. To be honest, I find it difficult to answer this question, as a woman in my mind is something divine, a cosmic phenomenon. God gave her such great power that everything that happens on the planet is associated with them – with women. For me, there is no concept of “beautiful” or “ugly”. For me, all women are beautiful. I love them all just because they are women, and that's it.

Have you ever had the desire to change the world? If you had the power, what would you change first?

First, I would never want to have the power. I'm not perfect. Not perfect in the sense that it is unlikely I would be able to give people what they would like to have. Second, I believe that someone who aspires to power should be obliged to meet the requirements of the people. When I see people striving for power, I just wonder if they are so confident of their abilities. Heck, how strong a person has to be and at the same time not free from themselves to be able to manage. And I love the freedom in me, so for myself it would be very hard.

But going back to the heart of the question, I probably would not have allowed changes to the city in which we live. I would not have allowed Baku to become a city of “corncobs” [new high-rise buildings – Ed.]. I would leave only four- or five-storey buildings in the city centre. I would clean up the filthy Caspian Sea, on the shores of which I spent my childhood and adolescence. What else? Of course, I would like to be back home in Khankendi where I was born and spent my early childhood, my legs dangling over the gorge, to plunge myself mentally into the abyss of my native Jidir. Believe me, I have travelled a lot, travelled all over Europe, but I have never seen such a rich palette of colours as in Karabakh, Khankendi. As for myself, I would not change anything in me.

What about people? What would you like to change in them, because the city is not only buildings and streets, it is also the people who inhabit it?

You know, I remember a fragment from an American movie about aliens, where a stranger says, “You people are amazing creatures. You show your best qualities only when you are going through hard times and feel bad.” So, I would say to people that there is no need to wait till we feel bad to show our best side. You just have to love people, love each other, here and now.

Fakhraddin Manafov in Brief

Born on 2 August, 1955 in Khankendi, Karabakh.

Graduated from the State Institute of Art of Azerbaijan.

Began his film career in the late 1970s.

Joined the Jaffar Jabbarli Azerbaijanfilm Studio in 1982. Starred in films for Uzbekfilm and Mosfilm.

Acted in stage plays including Them and Him and Like a Lion.

Film credits include Murder on the Night Train, Another Life, Temple of Air, Window of Sorrow, Business Trip,

Tahmina, Park and Goodbye, Green of Summer.

Some of his most recent film credits are Mahmoud and Maryam, Dawn Herald, Destiny of a Sovereign,

Hindu, Weapon, Drongo and Farewell, Southern City!

Won the Zirva prize for his performance in Destiny of a Sovereign.

Awarded the title People's Artist of Azerbaijan.

.jpg)