In a series of articles for Visions, veteran travel writer Mark Elliott returns to a series of destinations he first covered for his Trailblazer guidebook nearly two decades ago, and reflects on the changes. In this piece he revisits the exclave of Nakhchivan, the south-western corner of the Azerbaijan Republic. With Noah connections, abrupt rocky crag-mountains, wild-west style badlands and green meadow-ringed lakes, it’s a fascinating place but is divided from the rest of the country by an uncrossable sliver of hostile Armenia.

I’m in a taxi, gliding along a new highway heading out of Nakhchivan City. And something is wrong. No, let me correct that. Nothing is wrong – and that’s what feels odd. Things simply feel a bit too perfect. The ranks of new ministry buildings that now line the thoroughfares of Nakhchivan City look to have materialised straight out of an architect’s catalogue. The road seems just too tidy – smooth, wide and devoid of traffic. My driver, Emil, speaking remarkably decent English, has appeared as though by magic, keen to show me around for a token “petrol only” fee. Not many foreigners come to Nakhchivan, but everyone is surprised by the place, says Emil. I had a client from somewhere in Central Europe who described Nakhchivan as being “like Switzerland”. For a moment I’m baffled. Certainly Nakhchivan has its peaks – craggy and dramatic, but they are forged from bare desert rocks and Biblical myths rather than cowbells and Sound of Music serenades. It’s not the scenery, Emil clarifies, it’s the standard of the infrastructure, the quality of the roads. My friend told me that nowhere else in Europe are driving conditions as good as this. Except Switzerland.

He has a point. And there’s certainly no rush hour jam. But there weren’t any traffic jams 15 years ago either. What is more interesting to me are the attitudinal changes in this fascinating exclave. Don’t get me wrong, the welcome from local people has always been one of overwhelming hospitality. But in past years, my mere presence seemed to cause widespread consternation in officialdom. In researching all four previous editions of my guidebook, I had sensed Soviet-style degrees of official suspicion towards independent travellers. On the train from Nakhchivan City to Julfa, I’d been unable to really enjoy the spectacular Araz Valley views due to insistent and officious interrogation. Perhaps I could understand that that particular journey seemed ‘suspicious’ as the railway line does follow the Iranian border very closely. But other occasions were far less explicable. Anyway, the good news is that this year, while I didn’t test the train again, I can report travelling quite freely throughout Nakhchivan without suffering a minute of police interest.

Batabat

Let’s start with Batabat, Nakhchivan’s unexpectedly green, bird-filled mountain lake complete with curious ‘floating island’, close to the sensitive Armenian border area. En route one passes through the small town of Shahbuz. In previous editions of my guide I have written of Shahbuz foreigners are supposed to sign in at the police station. On one occasion that process took me over an hour of farcical, if not unamusing, banter. I was being polite – the amusement was largely in retrospect after a rather gruelling good-cop/bad-cop interrogation which seemed all the more unnecessary for the fact that I’d turned up quite voluntarily to report my trip as I thought I was supposed to. Now, however, there seems to be no need to stop at all in Shahbuz unless one is visiting the sweet little museum where a handful of grave stones inscribed in Arabic are bizarrely claimed to be “Albanian”. Or to avail oneself of Nakhchivan’s cheapest accommodation – the 5 AZN box-rooms in a tiny unnamed mehmanxana around 200 metres further south.

Ordubad

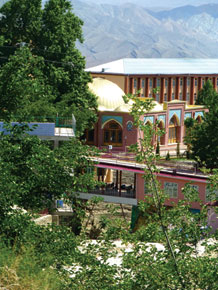

In previous trips, my most frequent brushes with authority had been in Ordubad, which, ironically, is also my favourite town in the exclave. It’s a peaceful gem of a village with sloping streets of walled orchard gardens, historic buildings and old mud-walled homes that lead steadily up to the lemon groves for which the town is famed. Understandably there are plenty of scenes to tempt tourists to whip out their cameras. However, that was not necessarily appreciated in years gone by. In 1997, my apparently innocent wanderings had been interrupted by an ‘invitation’ to a local house which proved to be impossible to refuse. I was ushered onto an attractive balcony ostensibly for tea. But soon the police arrived for a fairly intensive questioning. The experience proved to be a very curious mixture of angry accusation and hospitable kindness, each volley of questions interspersed with invitations for another glass of tea or spoon of conserve. My ‘crime’, I was eventually led to understand, was that I’d snapped a photo which probably included a mountaintop whose peak formed the Armenian border. I was eventually allowed to go, but the experience left a strong impression.

As late as 2008, an Ordubad taxi driver told me that he couldn’t change our proposed route because he “hadn’t told them”, “them” being an apparent reference to the KGB-equivalent service to which he had had to report before our departure. But by the time of my return in 2014, things appeared to have relaxed enormously. My presence no longer seemed to turn heads. Those who did approach me did so to ask if I needed help. Or simply to offer a shy greeting before retreating into the youthful new tea terraces beside the central stream. My confidence grew such that I started blatantly, if casually, photographing a whole series of views of landscapes and of Ordubad’s heavily restored historic monuments. Taxi drivers that ferried me around made no apparent reports to anyone.

Nakhchivan-Turkey border

Perhaps the worst experience that I remember from days gone by was the blatant extortion at the Nakhchivan-Turkey border. Back in the late 1990s, a guard on the Azerbaijani side had taken my passport, then claimed I’d never given it to him. That was “a problem”. But fortunately he knew someone who could help me. And with that he introduced a dapper fixer dressed entirely in black. Essentially the deal was that I pay US$100 and my passport could be “found”. Remarkably there was some leeway for negotiating price and I finally got the fee down to $30. Indeed I was later rather pleased to discover that the researcher for Lonely Planet had ended up paying far more than me. But the experience was traumatic. And the situation appeared to have remained bad for several years. Crossing the same border around 2002, the prices seemed to have fallen and become systematised: the driver of the Turkish bus in which I travelled collected a fee from each passenger and arranged any necessary ‘fees’ on our behalf. All seems to have changed now.

This year there was no fee whatever. At least so it had seemed. Then, when I had almost finished with the formalities I started to panic. A man dressed all in black was approaching and, yes, he wanted to talk to me. But it was not as I feared. This fellow, it turned out, had purely come to offer some suggestions on places to see in Nakhchivan. Have there been many foreign travellers through today? I asked him.

Europeans? No. I think you’re the first of the whole month.

Later in the trip I tested another of Nakhchivan’s international borders, crossing into Iran at Julfa. This proved even friendlier – and the experience has the added perk of a fabulous view from the Araz River bridge as one walks across. Shame one can’t photograph that.

Nakhchivan City

But bef ore we leave, some words about Nakhchivan City. The exclave’s one major city has been busily reinventing itself. The cheap, nasty $10 hotels that once catered to Iranian booze-tourists have closed down since Azerbaijan started imposing hefty visa fees on their brothers south of the border. This has essentially put off the vast majority of tourist visitors, including the Iranian families who once came to Nakhchivan City’s top hotel, Duzdag. This fascinating place is set 10km out of town and offers a unique opportunity to sleep on comfortable beds in an ex-Soviet salt mine, tunnels to which start nearby. Making up for the lost Iranian customers, Duzdag has been trying to develop local clientele by adding a range of sports activities.

Meanwhile Nakhchivan City’s most central major hotel, the Tabriz, has installed a decent swimming pool and spa. Historic buildings have been re-purposed – the Khan’s Palace no longer hosting a carpet museum, the 18th century domed bath-house now a chaykhana and the buzkhana, a medieval ice-house, converted into a curious restaurant where diners might feel they’re in a half-buried chapel.

Behind an embankment directly above the buzkhana lie the city’s two most astonishing 21st century novelties. Illuminated with strings of coloured lights at night, Nakhchivanqala is the city’s ‘ancient’ citadel. As recently as 2009 the site was just a series of indistinct mud walls, but now there is a complete rectangle of crenulated fortress walls. Obviously a lot of work and investment has gone into this reincarnation, though the walls’ stone cladding looks more suitable for a Sussex patio than an historic castle. In the middle of the area enclosed by these walls is a large circular museum pavilion, its ceiling painted with clouds in an artificial sky and its collection – free to visit like all Nakhchivan’s museums – showing the vast wealth of artefacts found when the site was excavated for the reconstruction. One pot, with petroglyph-style figures, apparently dates back 6,000 years.

But that’s youthful compared to the site next door, a tomb tower reputed to mark the grave of the Bible’s great zookeeper, Noah. The brickwork is perfect, the dome edging freshly gleaming with bronze-effect cladding. Altogether it looks entirely new, a suspicion not entirely dispelled by photos of President Ilham Aliyev at its official opening ceremony. But with chutzpah of Biblical proportions the tower is inscribed as an historical monument of the 7th millennium BC. Noah would have approved.

Organising a quick flit through Nakhchivan

For those with no visas, starting in Turkey

For years I’ve been touting the niche tourist potential of the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic as an ‘adventurous’ transit route between Turkey and Iran. Such a transit would offer visitors a great opportunity to see some little visited gems and, for those who enjoy traveller one-upmanship, popping through Nakhchivan allows you to ‘notch up’ another territory on bragging sites like www.mosttravelledpeople.com. Sadly, for years the whole idea of such a journey has been hampered by the difficulty of arranging the visas. But for now, for many nationals (including EU citizens other than Brits and Danes) it’s extremely easy to get an Iranian tourist visa in Trabzon, eastern Turkey. The visa is available the same working day with no invitation or extraneous paperwork. Just pay the equivalent of 75 euros into a specific city centre bank and return around 4.30pm to collect the visa. Magic! For South Koreans and Japanese tourists it’s just as easy, and much cheaper. The only minor caveat, for women, is that you’ll need to wear a scarf for the visa photo, just as you will throughout the Islamic Republic once you get there.

Having bagged your Iranian visa there’s plenty of time to reach Trabzon bus station in time for an overnight bus to Tbilisi, Georgia. Most nationalities no longer require visas for visiting Georgia and the Azerbaijani embassy in Tbilisi is prepared to grant an Azerbaijani transit visa for just US$20/40 single/double if you can show them your Iranian visa. You’ll need to wait around three working days, but that’s a pleasure in a city as magical as Tbilisi. The transit visa gives you up to five days per entry in Azerbaijan – an ideal amount of time for visiting Nakhchivan. Armed with your new visas, you’re ready to embark on a classic Caucasian journey to Tabriz via Nakhchivan. En route sights include Stalin’s home town (Gori), the pretty spa resort of Borjomi, the castle crowned cities of Akhaltsikhe, Ardahan and Kars and the forgettable, but very welcoming, Turkish city of Igdir whose central park is now named for Heydar Aliyev. From Igdir, Ilham Aliyev Boulevard leads towards the small nose of Turkish territory that creates a crucial link with Nakhchivan. Over a dozen daily buses make the journey between Igdir and Nakhchivan City, albeit taking a couple of hours at the border.

If you are staying more than two days in Nakhchivan, don’t forget to get your visa registration, even when using a transit visa. [As of January 2015, only visitors spending 10 days or more in Azerbaijan have to register at their place of stay. However, it is worth checking the Azerbaijan Migration Service website for any changes in the rules. Ed.] The main city hotels will generally register on your behalf without prompting, but it’s worth checking. Once you’ve made the most of your time in Nakhchivan, continuing to Iran is very simple at the friendly, efficient, 24-hour Julfa border. One original way to get to that frontier is to visit Ordubad in the afternoon, then take the 5pm bus (1 AZN) from Ordubad’s petite bus station to the Julfa border post. However, one wonders how long that service will survive – I was one of only two passengers aboard when making the trip. My co-passenger was so endlessly effusive in his hospitality that it was as much as I could do not to be yanked off the bus at his home to enjoy fresh kebab and a flagon of mulberry hooch.

The Julfa border is a bridge across the very picturesque Araz River. Directly across on the Iran side are a series of money changers who offer remarkably fair rates. Their honesty is fortunate as all the zeros on Iranian bills can prove baffling, especially as bank notes are denominated in rials, while in conversation everyone talks in tomen (ten times the value of the rial). Finding a shared taxi to Tabriz is a breeze – continue walking away from the border post, then look to your right immediately before the pedestrian street hits a traffic circle. There are two lines of cars here with a bus-stop style shelter for passengers to wait. Cars on one side head to Tabriz (2½ hours), on the other to the Bilasuvar border post, ideal for Azerbaijanis in a hurry to reach Baku. If reaching Tabriz by day, head straight to the remarkably helpful tourist office in the lane that leads to Tabriz’s magnificent covered bazaar. They have free maps and plenty of great advice that will help you feel swiftly at home.

About the author: Mark Elliott’s guidebook Azerbaijan with Excursions to Georgia was first published in 1998 is and now in its 4th edition.