Azerbaijan’s Carpet Museum, formerly boasting the cumbersome title of State Museum of Azerbaijan Carpet and Applied Art, reopened its doors in September 2014 following a highly anticipated move from the second floor of Baku’s Museum Centre to a grand carpet-shaped building on the Boulevard. Visions’ Tom Marsden recently paid a visit to admire the museum’s new home as well as the world’s largest collection of Azerbaijani carpets.

A carpet is like a love letter to the sun, said Tariyer Bashirov, a carpet artist who teaches at the European Azerbaijan School, noticing my general look of confusion and disorientation after two hours of learning about carpet history, types, weaving techniques and the various regional traditions and carpet schools in Azerbaijan. This simple explanation relaxed me, the need for deep analysis and interpretation disappeared and I could simply wander the museum’s three floors at my own leisure, admiring the complex fusion of patterns, colours, symbols and motifs encountered on rugs of various shapes and sizes, techniques and place of origin.

The one thing in common is that the museum’s collection of roughly 6,000 carpets were all designed and woven by Azerbaijanis, whether originating from Quba, Qazakh, Baku, Tabriz or Karabakh and as such the Carpet Museum highlights the uniquely Azerbaijani origins of many carpets that might otherwise be broadly categorised as Caucasian or Persian on the global carpet market.

A few hours before Tariyer uttered this simple simile, I entered the elaborate rug-shaped building that sits side by side with another Azerbaijani cultural treasure, the Mugham Centre, on Baku’s rapidly expanding and developing Seaside Boulevard, stretching along the Caspian seafront. An Azerbaijani musician had recently told me that mugham was something that foreigners couldn’t fully understand, just as an Azerbaijani couldn’t precisely replicate English sounds or decipher English poetry, and similarly I wondered how effectively a foreigner with little carpet expertise could weave through Azerbaijan’s rich carpet history.

The Carpet Museum first opened in 1967 and initially occupied a small mosque in Icheri Sheher (Old City) before moving in 1992 to the Baku Museum Centre, formerly the Lenin Museum. According to Yalchin, a passionate carpet enthusiast based at the museum, President Ilham Aliyev requested a new home be built for the world’s largest collection of Azerbaijani carpets after visiting the museum’s cramped quarters in the old Lenin Museum. The museum’s third incarnation now occupies three spacious, contemporary exhibition floors, complete with a café, children’s section, gift shop and offices on the ground floor. Beyond the vast collection of carpets, there are also several displays covering jewellery, metal work, ceramics and Azerbaijani national dress.

The original museum was founded largely on the initiative of Latif Kerimov, Azerbaijan’s most celebrated carpet artist and expert of modern times. Born in Shusha at the turn of the twentieth century, Kerimov spent much of his youth in Iran, where he learnt the craft of carpet weaving and later travelled, exhibiting his carpets throughout Iran. Kerimov briefly worked for state radio in Baku during World War II and then spent the rest of his life researching, teaching and promoting the art of carpet weaving through books, courses and exhibitions.

Tariyer was one of Kerimov’s students and emphasized his work ethic and artistic skill, which enabled Kerimov to not simply design carpets but to understand all the technological processes inherent in the weaving process. He worked day and night, Tariyer explained, he was a person who knew lots about lots of different things. He knew music well, he knew history well, he could recite poems off by heart. According to Tariyer, people used to consult Kerimov from all over the Soviet Union, as the premier source of knowledge on Azerbaijani carpets.

It was Kerimov too who studied and classified the regional themes and variations of Azerbaijani carpets, which are explored on the second floor of the new Carpet Museum, which exhibits pile carpets from each of the traditional Azerbaijani carpet-weaving schools – Baku, Quba, Shirvan, Ganja, Qazakh, Karabakh and Tabriz. Each school or region has its own particular nuances and styles, which can be difficult to distinguish for the untrained eye. Yalchin and Tariyer unravelled the colours and motifs and, like cracking a complex code, certain patterns began to emerge, such as the blue background common to Baku carpets, the vibrant colours of Karabakh and the intricate designs of Qazakh carpets, which often contain horns, swastikas, “S” shapes as well as depictions of flowers, branches and trees. In regions such as Quba, the multitude of carpet designs reflects the region’s rich ethnic diversity, which comprises Azerbaijanis, Lezghins, Tats, Budugs and Griz and carpet designs can differ from village to village.

Interpreting a carpet’s symbols, motifs and patterns, however, is far more complex than determining its region of origin. Each uniquely individual carpet is a creative fusion of intermingling regional, philosophical and artistic influences, blending geometrical figures with symbols of Islam, animals, plants and trees, inherited from different times and cultures. Even Yalchin and Tariyer seemed to have quite contrasting interpretations, eventually admitting that to be honest even we [at the museum] don’t even know what it all means.

There are certain common shapes and symbols with generally accepted interpretations, such as the cross, representing the sun and God, the tree of life, illustrating abundance, the dragon characterizing water, and the buta, which is often found particularly in Shirvan and Baku carpets and alludes to fire and love. Yet, whatever the intricate blend of geometric shapes and symbolism encountered, in many instances the carpets are perhaps best interpreted as the creative expression of the author’s (usually women’s) philosophy, experiences and way of life. The one thing to remember, according to Tariyer, is that carpets are not connected with religion, just with faith, and this is an important distinction. In ancient times people just worshipped the sun and we have kept this tradition, he says, and this is what makes Azerbaijani carpets both uniquely individual and a fascinating means of reflection on the country’s past.

In reality, such loosely based interpretations, together with the anonymous nature of many pre-twentieth century carpet authors, also add to the mystique surrounding the culture of Azerbaijani carpet weaving. According to the museum’s director Roya Taghiyeva, this culture originated with the ancient Turkic nomadic tribes who wandered the territory of today’s Azerbaijan and beyond, for whom carpets were an integral part of everyday life. Strong yet light and easily transportable, carpet products were fashioned into roofs, doors and curtains in Alachigs (tents), as tablecloths, decorations for horses and camels, for weddings and clothing, and bags to carry household items from one dwelling to another. The patterns depicted on carpets evolved with time to represent aspects of family life, philosophy and nature and, in short, carpets became so intertwined with daily life that without carpets, life didn’t exist, as Tariyer succinctly explained to me.

These diverse traditional uses of Azerbaijani carpets are displayed mainly on the museum’s first floor, which is also devoted to the other main type of Azerbaijani carpet – flat-woven. Flat-woven carpets are classified less according to region and rather by style and technique and include the kilim, shudda, ladi, varni, zili and sumakh. Their general characteristics are a smoother feel to pile carpets but equally stunning and intricate designs.

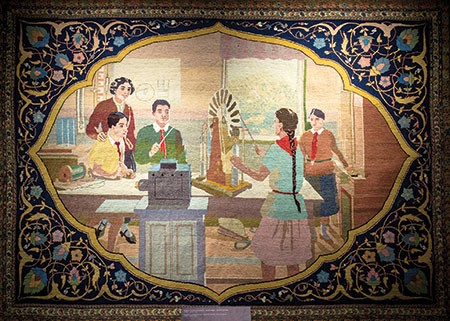

The museum’s third and final floor brings us into the modern era, leading visitors on a journey through Azerbaijani carpet weaving from the beginning of the twentieth century through to the Soviet period, represented by works of Soviet Realism such as Laboratory from 1969, and into the present with magical carpets adapted from artist Tahir Salahov’s vibrant paintings of cosmonauts, Baku and the oil industry in particular. A host of other influential modern day artists are also represented on the third floor, including work by my guide Tariyer Bashirov, as well as displays including black and white photographs of celebrated weavers, newspaper cuttings and even a dazzling colour portrait of Latif Kerimov.

Several hours after first stepping foot inside the new Carpet Museum, I wandered back onto the Boulevard with a far greater grasp of the differences between pile and flat-woven carpets and the nuances between carpets woven in the likes of Quba, Qazakh, Baku and Tabriz. But I also appreciated that Azerbaijan’s carpet culture has evolved greatly since the practical days of the nomadic Turkic tribes, and contributes today rather to a sense of national identity. With this in mind, the new Carpet Museum is not just a uniquely shaped building to wonder at on the Boulevard, but an intriguing visit for anyone interested in traditional Azerbaijani culture.

WEAVING THROUGH TIME AT AZERBAIJAN’S NEW CARPET MUSEUM

39950

0 COMMENTS

Only logged in users can leave comments

Login Registration