To mark Republic Day (28 May) and the founding of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic (ADR) in 1918, Visions unravels how Azerbaijan gained international recognition at the Paris Peace Conference in 1920.

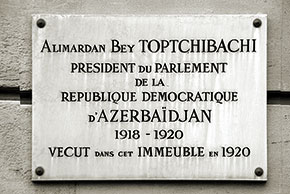

With the end of World War I, a delegation from the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic was sent to the Paris Peace Conference (January 1919-January 1920). Headed by Ali Mardan bey Topchubashov, the delegation’s main objective was to achieve recognition of Azerbaijan as an independent state by the Supreme Council established by the allied victors.

From mid-June 1919, the main obstacle facing the Azerbaijani, Georgian and North Caucasus delegations, formerly part of the Russian Empire, were counter claims from White Russians led by Admiral Alexander Kolchak for a united and indivisible Russia.

British differences

Although during the Russian civil war the British government had been Kolchak’s main wartime ally, supplying weapons, equipment and clothing to the Whites, there were sharp divisions over his post-war status.

Secretary of State for War Winston Churchill was a resolute supporter of Kolchak, Denikin and other White generals. Believing that the Caucasus should return to Russia following victory over the Bolsheviks, he saw British troops remaining there only to provide logistical support to Denikin (head of the White Volunteer Army - Ed).

Lord George Curzon, acting Foreign Secretary from summer 1919 and officially in post from October, disagreed strongly. A former Viceroy of India, he urged the creation of independent states in both the Caucasus and Central Asia to form an effective barrier against further expansion by Russia.

British Prime Minister David Lloyd George had no great sympathy with the White Russians and mediated relations between Churchill and Curzon. In principle he had no problems with the small nations of the former Romanov Empire, nevertheless, his main priority was to deal with the enormous financial burden resulting from the war. This was the context in which he viewed questions of military assistance to General Denikin’s Volunteer Army operating in southern Russia, and the maintenance of British troops in the Caucasus.

Although the Volunteer Army temporarily occupied the North Caucasus in late July 1919, posing a direct threat to Azerbaijan from Dagestan and the Caspian Sea, Denikin was dependent on military assistance from the Allied powers and decided against invading the South Caucasus.

British operations in the South Caucasus

In the same month, Curzon pushed through the appointment of Oliver Wardrop as British High Commissioner in the South Caucasus. Wardrop was a noted expert on the region and a convinced supporter of independence for the South Caucasus states. Even before his departure for Tiflis (Tbilisi), he submitted recommendations including recognition of independence for the South Caucasus states.

Wardrop visited the Azerbaijani delegation on 12 August, the day he departed for the South Caucasus, and made a good impression on Topchubashov, emphasising the need for Azerbaijan, Georgia and Armenia to work together as much as possible.

Upon his arrival in Tiflis on 29 August, Wardrop was greeted enthusiastically by the Georgian government and began at once to structure and organise his office. The British representative appointed to Baku was Colonel Claude Bayfield Stokes, a career intelligence officer who had previously been the British Military Attaché in Tehran from 1907-1911 and then in Indian army headquarters intelligence before World War I.

Like most British officers serving in India, Stokes was well aware of Russia’s imperial ambitions in the near East. He was very well disposed towards Azerbaijanis and strongly supported Azerbaijani and Georgian independence. In total agreement on the issue, Wardrop and Stokes attempted to persuade the British government to act similarly.

Initially they didn’t get the support they wanted because in September and October 1919 the Whites’ Volunteer Army had considerable military success and converged around Oryol, moving towards Moscow. Later, however, as the White Army suffered increasing reverses, the Supreme Council began to favour the South Caucasus nations.

Changing tide

Topchubashov caught on immediately and mentioned this in a report of 6-10 November.

On 11 December, Curzon, and Lloyd George raised the issue in London with French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau. Although aware of Denikin’s position, Clemenceau continued to oppose recognition of independence, declaring that he was against any attempt to found separate states that would give the Russians cause to claim an Allied dismemberment of their country. Nevertheless, the Anglo-French consultations on recognition continued.

In London on 22 December Curzon told Philippe Berthelot, Secretary General of France’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, that Britain wanted one of the great powers to have a mandate over the Caucasus. Britain was protecting the South Caucasus countries against Denikin, but couldn’t recognise them without taking on a certain degree of responsibility. At that stage Curzon wanted the Caucasus states to cooperate and be afforded autonomous status. Following a hoped-for victory over the Bolsheviks, he saw them in federal alliance with a recovered Russia.

Two days later, he submitted a special memorandum recommending recognition of independence for Georgia and Azerbaijan, noting that of the South Caucasus republics, Georgia and Azerbaijan were most capable of independent existence, and that their fates were intertwined.

De facto or de jure?

By early January 1920, recognition of Azerbaijan and Georgia in one form or another was imminent. On 2 January, British Foreign Office experts prepared a report on the type of recognition to be given. It read: We understand that the essence of de facto recognition is that it should be conveyed by a definite notification that recognition is accorded and that it differs from de jure recognition only in the fact 1) that in the case of a State such as Azerbaijan, which has had no previous independent existence, de facto recognition is a necessary step to the grant of de jure recognition, and 2) de facto recognition involves a qualification to the effect that it is only granted on a specified condition such as e.g. the maintenance of stable Government or the decision of a Conference.

The immediate effect of de facto recognition would be to satisfy the large body of opinion in both States which suspects the policy of the Allies to be merely one of waiting until the Republics can be handed over to a reconstituted centralized Russia. All our information goes to show that this feeling is very widespread and its existence prevents the present Governments in either State receiving the support against Bolshevism, and in the case of Azerbaijan against pro-Turkish influences, which it might otherwise do.

At the same time, the allies would have only a moral responsibility regarding these states. London would not prevent them from signing a contract with the Bolsheviks on conditions favourable for them, it would simply be strengthening their position and making it difficult for the Bolsheviks to crush and include them in the Bolshevist system.

For these reasons the Foreign Office concluded that at that point de facto recognition corresponded to the wishes of the republics but de jure recognition would depend on the decision of the League of Nations or the allies.

The final straw

The final push for recognition was likely a telegram from Wardrop to London on 9 January. He reported that Colonel Stokes had written to him about a meeting with Azerbaijani Minister of Foreign Affairs Fatali Khan Khoyski.

Khoyski had received a telegram from Bolshevik Commissioner for Foreign Affairs Georgiy Chicherin, proposing that Azerbaijan and Georgia join the Bolsheviks in attacking the Whites’ Volunteer Army. Stokes believed that the Bolsheviks could force Azerbaijan’s hand. Khoyski had warned that although the Azerbaijani government was strongly anti-Bolshevik, if Great Britain will not come to its assistance, it [the Azerbaijani government. Ed] may be compelled to make terms with the Bolsheviks.

Stokes did not believe that Khoyski exaggerated the danger: Unless we are willing to see the Bolsheviks rampant in Azerbaijan a decision to support that country cannot be taken too soon. Considering the gravity of the situation following the defeat of the White Army, Stokes recommended:

Immediate grant of full independence and whole-hearted support to Azerbaijan, dispatch of arms and equipment including uniforms for her army and of breach blocks and ammunition for two six-inch guns at Baku.

He argued further for prompt payment of money owed Azerbaijan for the British force’s stay in the country. These steps, Stokes believed, could keep the Bolsheviks at bay.

To protect the South Caucasus from a Bolshevik invasion, he reasoned, the British would have to control the Caspian Sea; this would mean returning Denikin’s fleet to British command and replacing its demoralized personnel with British sailors. To do this the British admiralty would require secure communications from Baku to Batumi on the Georgian Black Sea coast.

Thus, Stokes skilfully tied in control of the Caspian with the question of status for Azerbaijan and Georgia. Clearly aiming to counter those who favoured Russian imperial integrity, he stressed that for Baku and Tiflis, no promise of autonomy in any shape given by any existing Russian Governate even if guaranteed by the Allies will carry any weight.

The policy advised above may be regarded as drastic but in my opinion half measures would be of no avail and delay would mean disaster, he wrote. I entirely concur, added Wardrop at the bottom of Stokes’ message.

Independence granted

At a meeting in Paris on 10 January 1920, the allied Ministers of Foreign Affairs agreed to recognise Azerbaijan and Georgia de facto.

According to Curzon, Lloyd George proposed that Armenia’s fate be decided separately by a peace conference, within a settlement of the Turkish problem. As for Georgia and Azerbaijan, countries that had been under triple threat from Denikin, the Bolsheviks and the Turks, Lloyd George suggested the same de facto recognition as given to the Baltic countries.

Philippe Berthelot reported that Georges Clemenceau gave his support on condition that the two countries’ borders with Armenia would be established subsequently. Curzon agreed to this.

Vittorio Scialoja, Italy’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, also inclined towards de facto recognition on the same conditions as the Baltic countries. Hugh Wallace and Matsui Keishirō, the US and Japanese representatives, declared that they would seek their governments’ opinions. Meanwhile, Berthelot noted that de facto recognition of Azerbaijan and Georgia had to be a collective decision of the Supreme Council.

As a result, the meeting’s minutes read: the Principal Allied and Associated Powers should together recognise the Governments of Georgia and Azerbaijan as “de facto” Governments, subject to the reserve that the representative of the United States and the representative of Japan would request instructions from their Governments on the question.

The same day, Lord Curzon sent a telegram to the British Ministry of Foreign Affairs, reporting that on his initiative the Supreme Council had decided to recognise Azerbaijan and Georgia de facto and that Foreign Office representatives could inform the governments of those two countries.

However, the telegram also emphasised: Recognition of de facto independence of the Georgian and Azerbaijani Governments does not of course involve any decision as to their present or future boundaries, and must not be held to prejudice that question in the smallest degree.

Wardrop reported the news to the governments in Tiflis and Baku two days later. By this time, the Azerbaijani delegation in Paris had also been informed, although the official text of the resolution was only given to the Azerbaijani delegation on 30 January, after a special appeal to the conference secretariat.

Significance

De facto recognition opened new horizons for the Azerbaijani delegation in Paris. Sure of the country’s adherence to the principles of independence and governmental stability, the western powers were now ready for new forms of cooperation with Baku.

That the Bolsheviks subsequently trampled over Azerbaijani independence at the end of April 1920 meant a temporary, albeit lengthy, victory for brute force. But from a historical standpoint, the Azerbaijani people’s desire for independence proved to be unshakeable, as evidenced some 70 years after the events we have described.

About the authors: Georges Mamoulia has worked in France since 2003. He is a Doctor of the École des hautes études en sciences sociales and the author of many works on the Caucasus.

Ramiz Abutalibov works at the UNESCO Secretariat based in Paris dealing with education, science and culture.

With the end of World War I, a delegation from the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic was sent to the Paris Peace Conference (January 1919-January 1920). Headed by Ali Mardan bey Topchubashov, the delegation’s main objective was to achieve recognition of Azerbaijan as an independent state by the Supreme Council established by the allied victors.

From mid-June 1919, the main obstacle facing the Azerbaijani, Georgian and North Caucasus delegations, formerly part of the Russian Empire, were counter claims from White Russians led by Admiral Alexander Kolchak for a united and indivisible Russia.

British differences

Although during the Russian civil war the British government had been Kolchak’s main wartime ally, supplying weapons, equipment and clothing to the Whites, there were sharp divisions over his post-war status.

Secretary of State for War Winston Churchill was a resolute supporter of Kolchak, Denikin and other White generals. Believing that the Caucasus should return to Russia following victory over the Bolsheviks, he saw British troops remaining there only to provide logistical support to Denikin (head of the White Volunteer Army - Ed).

Lord George Curzon, acting Foreign Secretary from summer 1919 and officially in post from October, disagreed strongly. A former Viceroy of India, he urged the creation of independent states in both the Caucasus and Central Asia to form an effective barrier against further expansion by Russia.

British Prime Minister David Lloyd George had no great sympathy with the White Russians and mediated relations between Churchill and Curzon. In principle he had no problems with the small nations of the former Romanov Empire, nevertheless, his main priority was to deal with the enormous financial burden resulting from the war. This was the context in which he viewed questions of military assistance to General Denikin’s Volunteer Army operating in southern Russia, and the maintenance of British troops in the Caucasus.

Although the Volunteer Army temporarily occupied the North Caucasus in late July 1919, posing a direct threat to Azerbaijan from Dagestan and the Caspian Sea, Denikin was dependent on military assistance from the Allied powers and decided against invading the South Caucasus.

British operations in the South Caucasus

In the same month, Curzon pushed through the appointment of Oliver Wardrop as British High Commissioner in the South Caucasus. Wardrop was a noted expert on the region and a convinced supporter of independence for the South Caucasus states. Even before his departure for Tiflis (Tbilisi), he submitted recommendations including recognition of independence for the South Caucasus states.

Wardrop visited the Azerbaijani delegation on 12 August, the day he departed for the South Caucasus, and made a good impression on Topchubashov, emphasising the need for Azerbaijan, Georgia and Armenia to work together as much as possible.

Upon his arrival in Tiflis on 29 August, Wardrop was greeted enthusiastically by the Georgian government and began at once to structure and organise his office. The British representative appointed to Baku was Colonel Claude Bayfield Stokes, a career intelligence officer who had previously been the British Military Attaché in Tehran from 1907-1911 and then in Indian army headquarters intelligence before World War I.

Like most British officers serving in India, Stokes was well aware of Russia’s imperial ambitions in the near East. He was very well disposed towards Azerbaijanis and strongly supported Azerbaijani and Georgian independence. In total agreement on the issue, Wardrop and Stokes attempted to persuade the British government to act similarly.

Initially they didn’t get the support they wanted because in September and October 1919 the Whites’ Volunteer Army had considerable military success and converged around Oryol, moving towards Moscow. Later, however, as the White Army suffered increasing reverses, the Supreme Council began to favour the South Caucasus nations.

Changing tide

Topchubashov caught on immediately and mentioned this in a report of 6-10 November.

On 11 December, Curzon, and Lloyd George raised the issue in London with French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau. Although aware of Denikin’s position, Clemenceau continued to oppose recognition of independence, declaring that he was against any attempt to found separate states that would give the Russians cause to claim an Allied dismemberment of their country. Nevertheless, the Anglo-French consultations on recognition continued.

In London on 22 December Curzon told Philippe Berthelot, Secretary General of France’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, that Britain wanted one of the great powers to have a mandate over the Caucasus. Britain was protecting the South Caucasus countries against Denikin, but couldn’t recognise them without taking on a certain degree of responsibility. At that stage Curzon wanted the Caucasus states to cooperate and be afforded autonomous status. Following a hoped-for victory over the Bolsheviks, he saw them in federal alliance with a recovered Russia.

Two days later, he submitted a special memorandum recommending recognition of independence for Georgia and Azerbaijan, noting that of the South Caucasus republics, Georgia and Azerbaijan were most capable of independent existence, and that their fates were intertwined.

De facto or de jure?

By early January 1920, recognition of Azerbaijan and Georgia in one form or another was imminent. On 2 January, British Foreign Office experts prepared a report on the type of recognition to be given. It read: We understand that the essence of de facto recognition is that it should be conveyed by a definite notification that recognition is accorded and that it differs from de jure recognition only in the fact 1) that in the case of a State such as Azerbaijan, which has had no previous independent existence, de facto recognition is a necessary step to the grant of de jure recognition, and 2) de facto recognition involves a qualification to the effect that it is only granted on a specified condition such as e.g. the maintenance of stable Government or the decision of a Conference.

The immediate effect of de facto recognition would be to satisfy the large body of opinion in both States which suspects the policy of the Allies to be merely one of waiting until the Republics can be handed over to a reconstituted centralized Russia. All our information goes to show that this feeling is very widespread and its existence prevents the present Governments in either State receiving the support against Bolshevism, and in the case of Azerbaijan against pro-Turkish influences, which it might otherwise do.

At the same time, the allies would have only a moral responsibility regarding these states. London would not prevent them from signing a contract with the Bolsheviks on conditions favourable for them, it would simply be strengthening their position and making it difficult for the Bolsheviks to crush and include them in the Bolshevist system.

For these reasons the Foreign Office concluded that at that point de facto recognition corresponded to the wishes of the republics but de jure recognition would depend on the decision of the League of Nations or the allies.

The final straw

The final push for recognition was likely a telegram from Wardrop to London on 9 January. He reported that Colonel Stokes had written to him about a meeting with Azerbaijani Minister of Foreign Affairs Fatali Khan Khoyski.

Khoyski had received a telegram from Bolshevik Commissioner for Foreign Affairs Georgiy Chicherin, proposing that Azerbaijan and Georgia join the Bolsheviks in attacking the Whites’ Volunteer Army. Stokes believed that the Bolsheviks could force Azerbaijan’s hand. Khoyski had warned that although the Azerbaijani government was strongly anti-Bolshevik, if Great Britain will not come to its assistance, it [the Azerbaijani government. Ed] may be compelled to make terms with the Bolsheviks.

Stokes did not believe that Khoyski exaggerated the danger: Unless we are willing to see the Bolsheviks rampant in Azerbaijan a decision to support that country cannot be taken too soon. Considering the gravity of the situation following the defeat of the White Army, Stokes recommended:

Immediate grant of full independence and whole-hearted support to Azerbaijan, dispatch of arms and equipment including uniforms for her army and of breach blocks and ammunition for two six-inch guns at Baku.

He argued further for prompt payment of money owed Azerbaijan for the British force’s stay in the country. These steps, Stokes believed, could keep the Bolsheviks at bay.

To protect the South Caucasus from a Bolshevik invasion, he reasoned, the British would have to control the Caspian Sea; this would mean returning Denikin’s fleet to British command and replacing its demoralized personnel with British sailors. To do this the British admiralty would require secure communications from Baku to Batumi on the Georgian Black Sea coast.

Thus, Stokes skilfully tied in control of the Caspian with the question of status for Azerbaijan and Georgia. Clearly aiming to counter those who favoured Russian imperial integrity, he stressed that for Baku and Tiflis, no promise of autonomy in any shape given by any existing Russian Governate even if guaranteed by the Allies will carry any weight.

The policy advised above may be regarded as drastic but in my opinion half measures would be of no avail and delay would mean disaster, he wrote. I entirely concur, added Wardrop at the bottom of Stokes’ message.

Independence granted

At a meeting in Paris on 10 January 1920, the allied Ministers of Foreign Affairs agreed to recognise Azerbaijan and Georgia de facto.

According to Curzon, Lloyd George proposed that Armenia’s fate be decided separately by a peace conference, within a settlement of the Turkish problem. As for Georgia and Azerbaijan, countries that had been under triple threat from Denikin, the Bolsheviks and the Turks, Lloyd George suggested the same de facto recognition as given to the Baltic countries.

Philippe Berthelot reported that Georges Clemenceau gave his support on condition that the two countries’ borders with Armenia would be established subsequently. Curzon agreed to this.

Vittorio Scialoja, Italy’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, also inclined towards de facto recognition on the same conditions as the Baltic countries. Hugh Wallace and Matsui Keishirō, the US and Japanese representatives, declared that they would seek their governments’ opinions. Meanwhile, Berthelot noted that de facto recognition of Azerbaijan and Georgia had to be a collective decision of the Supreme Council.

As a result, the meeting’s minutes read: the Principal Allied and Associated Powers should together recognise the Governments of Georgia and Azerbaijan as “de facto” Governments, subject to the reserve that the representative of the United States and the representative of Japan would request instructions from their Governments on the question.

The same day, Lord Curzon sent a telegram to the British Ministry of Foreign Affairs, reporting that on his initiative the Supreme Council had decided to recognise Azerbaijan and Georgia de facto and that Foreign Office representatives could inform the governments of those two countries.

However, the telegram also emphasised: Recognition of de facto independence of the Georgian and Azerbaijani Governments does not of course involve any decision as to their present or future boundaries, and must not be held to prejudice that question in the smallest degree.

Wardrop reported the news to the governments in Tiflis and Baku two days later. By this time, the Azerbaijani delegation in Paris had also been informed, although the official text of the resolution was only given to the Azerbaijani delegation on 30 January, after a special appeal to the conference secretariat.

Significance

De facto recognition opened new horizons for the Azerbaijani delegation in Paris. Sure of the country’s adherence to the principles of independence and governmental stability, the western powers were now ready for new forms of cooperation with Baku.

That the Bolsheviks subsequently trampled over Azerbaijani independence at the end of April 1920 meant a temporary, albeit lengthy, victory for brute force. But from a historical standpoint, the Azerbaijani people’s desire for independence proved to be unshakeable, as evidenced some 70 years after the events we have described.

About the authors: Georges Mamoulia has worked in France since 2003. He is a Doctor of the École des hautes études en sciences sociales and the author of many works on the Caucasus.

Ramiz Abutalibov works at the UNESCO Secretariat based in Paris dealing with education, science and culture.