This is the first of a two-part article on Azerbaijan in 1918 during the First World War. This first part looks at the situation in Azerbaijan at the start of 1918 and the strategic thinking behind the British decision to send an expeditionary force to prevent Baku falling into the hands of advancing Ottoman forces. The second part will examine life in Baku when besieged by Ottoman forces in the summer of 1918 and will assess whether the British strategy of defending Baku against the Ottomans was a success or failure.

1917: COLLAPSE OF THE RUSSIAN ARMY

Following the revolutions in Russia in 1917, the Russian army started to disintegrate. Politicised and with discipline breaking down, soldiers began returning home. Unpaid and unfed, the soldiers looted and terrorised their way back home, fostering a general breakdown in law and order.

A British Intelligence assessment in January 1918 reported that there was a gradual spread of anarchy throughout Trans-Caucasia, and that, Turkish Kurds, Persian bandits, Moslem troops and Russian soldiers returning from the front [are] causing widespread destruction and loss of life.

Just as Russian troops were withdrawing, Armenian troops from eastern Anatolia, described by British military intelligence in February 1918 as simply [an] unbridled band who rob and murder, were also withdrawing into the South Caucasus. The British War Cabinet was told that the,

general situation had become alarming in [the] South Caucasus. Collisions, with much loss of life, were taking place between Russian soldiers returning from the front and Moslem troops, tribesmen, and Persian brigands. A brigade of mixed nationalities was being formed at Tiflis [now Tbilisi] with a view to the pacification of disturbing elements.

For a broken and demoralised Ottoman army, however, the collapse of Russian forces was a golden opportunity to recover some lost ground.

An armistice between Russia and the Ottomans came about in December 1917. In March 1918, there followed the Brest-Litovsk Treaty, which returned to the Ottomans the three territories of Kars, Ardahan and Batumi surrendered to the Russians in 1878. That posed a problem for the Armenians, whose numbers and influence had grown in eastern Anatolia and the South Caucasus, and the Georgians, who saw Batumi (predominantly populated by Georgian Muslims) as theirs. Neither was willing to give up these territories without a fight.

BRITAIN INTERVENES

From the perspective of Britain and France, the exit of Russia from the war was a disaster. It freed up more German divisions to fight on the Western Front, and it potentially opened up Ukrainian grain, Russian platinum, Georgian manganese, Caucasian oil, and Trans-Caspian cotton to Germany. Britain also fretted over what a successful Turkish advance into the Caucasus would mean for India. After all, there were upwards of 30,000 prisoners of war (on Nargin island, off Baku, and in western Turkestan) who could be used by the Central Powers to build the nucleus of an ‘instant’ army that could potentially threaten India. As early as February 1918, it was reported that 30 Turkish prisoners had reached Kasma, in Persia, from Baku.

Britain did not have any spare divisions to send to the Caucasus to beat back any challenge from the Central Powers. So a plan was devised whereby a bored Russian-speaking Indian Army officer, Brigadier-General Dunsterville, was to be tasked with leading a force of some 200 hand-picked officers and a similar number of non-commissioned officers to Tiflis where he was to raise, train and equip local Georgian and Armenian militias to withstand the expected advance into the Caucasus by Ottoman and German troops. Dunsterville’s command was nicknamed ‘Dunsterforce’.

Major-General Dunsterville, as he now became, sailed for Basra in January 1918. From there, he intended to make his way, via Baghdad and Hamadan, to the port of Enzeli, then by ship to Baku and finally by train to Tiflis. But Dunsterville found the route to Tiflis was blocked and so his mission morphed into something much less well-defined (more along the lines of raising and training militias in Persia and famine relief).

Baku at this time was dominated politically by Armenians and Russians. As early as April, Dunsterville was receiving requests from Armenians in Baku to come to their assistance. This he was in no position to do. His lines of communication were over-extended and, in any case, he did not have the troops. Added to that, both the Persian Caspian port of Enzeli (from which he would need to embark for Baku) and Baku itself were in the hands of the Bolsheviks, who were opposed to any British military intervention, and in Gilan, along the southern shores of the Caspian Sea, there were tribesmen hostile to British involvement in Persia.

Dunsterville wanted to see some action, as did the officers and NCOs who had signed up for what they thought was going to be a high-risk adventure in the Caucasus, not a famine relief effort. Dunsterville knew it was too late to go to Tiflis but he might still get to Baku and stop Baku oil and Caspian shipping falling into enemy hands.

Some have said that Britain’s sole interest in Baku was in grabbing its oil resources. This is not so, at least not before the end of the First World War. Britain’s objective was to prevent the control of the Caspian and the oilfields of Baku falling into the hands of the Central Powers, and it was a weak objective at that. Indeed, towards the end of May, Dunsterville received a cable, absolutely forbidding me to go to the Caucasus at the present time, ... I am to look after Persia only. The British War Office told Dunsterville that he was permitted to send one or more officers to Baku to report on: (a) the local situation; (b) the possibility of destroying the oil wells and pipelines; and (c) the possibility of acquiring or neutralising the Caspian fleet.

Dunsterville did not believe one or two officers could make any difference in Baku, which was looking to Britain for effective support, nor did he believe that there was a need to destroy the oilfields. He thought Baku could still be saved. His superiors did not agree: General Wilson, the Chief of Imperial General Staff was, even as late as June 1918, expressing the opinion that the despatch of troops to Baku or the assurance of armed help was both, inexpedient and dangerous.

Dunsterville continued to urge that a force be sent to Baku, believing, that the situation was more favourable than had been represented and there was a great possibility of organising [Baku’s] successful defence, saving the oilfields and securing the fleet.

As Dunsterville knew, inside Baku, British military intelligence was working to undermine the Bolshevik government and to turn the sailors and the fleet against it in preparation for the arrival of a British force.

While the political agents worked to undermine the Bolsheviks of Baku, Colonel Bicherakov with his 1200 or so Cossacks, had attached himself to Dunsterville’s command. Despite his well-known anti-Bolshevik views, he was offered, and accepted, the command of Bolshevik forces. It was decided that he should land with his Cossacks at Alyat, about 80 km south-west of Baku. He was to be accompanied by four British armoured cars and five Dunsterforce officers. Bicherakov left for Alyat on 3 June.

Enzeli was still occupied by the Bolsheviks, but they now had only 200 soldiers, too few to stop Dunsterville should he want to go to Baku. The relationship with the Bolshevik committee became a purely commercial one – they supplied petrol from Baku in exchange for motorcars, though not all the cars had been delivered by the time Dunsterville put the local Bolshevik committee under arrest and took control of the port.

For the moment, Dunsterville could do nothing further for Baku until he had more troops. But the 39th Infantry Brigade, together with a field artillery battery, was on its way.

Then, on 26 July, the Bolsheviks in Baku were thrown out of power and replaced by the Centro-Caspian Dictatorship. The British plan was now put into action. As Dunsterville put it,

The new Government had no sooner taken up the reins than, according to our pre-arranged plan, they sent messengers to us asking for help.

The first detachment of British troops arrived in Baku on 4 August. The main part of Dunsterforce arrived on 20 August. Dunsterforce withdrew from Baku on 14 September. What Dunsterville found when he arrived on 17 August was a Baku in peril of falling at any moment to the Ottoman-Tatar besieging force.

AZERBAIJAN IN TURMOIL

The Bolsheviks had been running the show since March 1918. The four main religio-ethnic groups – Russians, Georgians, Armenians and Azerbaijanis (‘Tatars’, or ‘Tartars’, as the Muslims of Russia were generally known in Western accounts) had all been represented in the Trans-Caucasian Federation, which tried to govern the South Caucasus first as part of Russia and then as an independent entity. However, the number of Armenians had been considerably boosted by refugees from Anatolia.

Tiflis, wrote the British historian Arnold Toynbee, has become a semi-Armenian city [with 160,000 out of a population of 330,000 - Ed]; and there has been a greater influx than ever during the present war. The number of new Armenian refugees from Turkey to the Caucasus has risen to 250,000.

Baku was not immune to the influx of Armenian refugees, bringing with it increased ethnic and social tensions.

These tensions burst into the open in Baku in March when many Muslims were massacred or driven out of the city. Lt.-Colonel French wrote in his memoirs, From Whitehall to the Caspian,

What was the Mussulman [Muslim - Ed] population of Transcaucasia to do in March 1918? Bolshevik troops and Armenians were slaughtering them. The Russian Caspian Flotilla bombarded their homes. Where were they to get help from?

The Georgians looked to the Germans. The Armenians looked to Britain and France. That left the Azerbaijanis in ‘no-man’s land’. So, they looked to the Ottomans. The British reported that the Azerbaijanis were:

violently anti-British in feeling, but by no means anxious to come under Turkish rule. They would like to return to their connection with Russia, either in a federal form or even by the restoration of the old regime. Their leaders, however, are pro-German.

… There is a movement among the Trans-Caucasian Tatars to detach [the Persian province of] Azerbaijan from Persia and unite it to themselves in an Azerbaijani-Tatar national State, possibly under Turkish suzerainty. ... This proposal, however, comes entirely from the [Azerbaijani] Tatar side, and finds no support in [Persian] Azerbaijan itself. (From the British National Archives – Ed.)

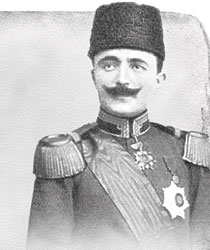

Ottoman troops were reported to have crossed into Persian Azerbaijan in April and Nuri Pasha, commander of the Ottoman forces in the Caucasus, entered Tabriz in May. The same month, Turkish officers were spotted in Resht, near Enzeli, Dunsterville’s only possible port of embarkation for Baku.

On 26 May, Georgia declared its independence. Armenia and Azerbaijan declared independence two days later. On the same day, Georgia entered into a treaty with Germany, ceding control of its railway to Germany.

For Azerbaijan, independence immediately led them into conflict with the government of Baku, the natural capital of an independent Azerbaijan but one which was controlled by the Bolsheviks.

On 4 June, the Azerbaijanis entered into a treaty of friendship and cooperation with the Ottomans where the latter agreed to provide much-needed military assistance, not only for the recovery of Baku but also for the suppression of Armenian guerrilla attacks in Upper Karabakh.

The Red Army pre-empted the situation and marched out of Baku in an attempt to seize the temporary Azerbaijani capital of Elizavetspol (now Ganja – Ed.). They had some initial success, beating back an Azerbaijani force on 26 June about 130 km west of Baku.

Meanwhile, the Ottomans, having set up their headquarters at Elizavetspol, set about establishing and training a Tatar Corps as part of its new Caucasian Army of Islam. The Ottomans found the situation in Elizavetspol chaotic. A British War Office memorandum reported:

From July onwards Nuri Bey [the Ottoman commander] ... was established at Elizabetpol with dictatorial powers and his stringent measures seem to have been successful in restoring order, but they occasioned great dissatisfaction among the local population.

The Red Army advance was halted at Goychay at the end of June. It fell back on Baku and the Ottoman-Tatar encirclement of Baku began. By 27 July, it looked all up for Baku. But, the Ottomans did not press home their attack, thus leaving an opportunity for the British under Dunsterville to reinforce the Baku defences.

[To be continued in the next issue of Visions]

About the author: Alum Bati is a barrister who has been living in Baku for over 21 years. He is also the author of Harem Secrets and Caravan to Paradise, a pair of historical thrillers set in Istanbul.