'God created people without words - he gave them movement, and people understood without words. Thoughts could not be hidden. The people asked God for help, "We need to be able to hide our thoughts," so God gave them words.’

Bakhtiyar Khani-zada laughs as he responds to the question, ´Why do you work without words?´ His thirst for openness of expression is shared by a devoted team of actors and a possibly even more devoted audience who, every weekend, squeeze into performances of the Azerbaijan State Pantomime Theatre. Khani-zada is its founder and Artistic Director.

We should probably explain here, for the benefit of British readers, that this Pantomime conforms to the second definition in the Oxford Dictionary: ´a dramatic entertainment in which performers express meaning through gestures´. There is none of the ´Look out, he´s behind you!´ - ´Oh no, he isn´t!´ shenanigans of a Christmas show in the UK.

But, in case you are worried, this does not rule out comedy.

One of the Pantomime Theatre´s best known pieces is a sketch in which three actors use red noses on their knees (yes, knees) to depict the singer, tar player and kamancha player of a traditional Azerbaijani mugham trio. Using a soundtrack by leading mugham singer Alim Qasimov, they celebrate both the joy and artistry of the music - and the comic foibles of the humans who produce it - to hugely enjoyable effect.

We had seen the Pantomime actors a few times on television, and had passed the theatre´s HQ many times without giving it much thought. As so often before, a chance meeting enticed us into a closer encounter with one of Azerbaijan´s under-advertised pearls. In this case ´pearl´ seems especially apt; this theatre shines its light on the human condition from deep inside the rough-edged shell of the decrepit Shafaq cinema, itself a former Baptist chapel, on Baku´s Azadliq Street.

At first sight we felt a little indignant that talented actors should have to work in such conditions: the stage is small and the auditorium four rows of assorted wooden benches, chairs and stools - capacity 60. This for a group which has performed from Russia to France, Saudi Arabia to Finland, Iran to Holland and many places in between. However,Rome was not built in a day. There are plans for refurbishment and, anyway, Bakhtiyar Khani-zada almost revels in the challenge.

In fact, in many ways, the poverty of resources actually suits mime. In the director´s view, ´In the end, theatre belongs to the actor. Theatres fail by not focusing on the actor and technology often swamps the actor... Wherever we are, see how many people gather round the actors! Perhaps they have seen a better spectacle, but they are delighted to see the real owners of theatre.´

This was reflected at a recent after show discussion in which the subject of the conditions inevitably came up. More than one member of the audience had mixed feelings about a ´better´ theatre - the pleasure of proximity to the actors and the action providing a bubble inside which the less-than salubrious surroundings cease to matter. In any case, says Khani-zada, ´We were given the cinema when it should have been closed for repair, so we are happy we can work. People come, you come, you´re writing this. I´m thankful we´re sitting here talking about theatre, not bad things. And saying "halva" won´t sweeten your mouth (fine words butter no parsnips?) - you have to do something.´

In fact, doing something was how this all started. After graduating from Azerbaijan and St Petersburg, Bakhtiyar muallim did some film acting and then taught stage work and choreography at Baku´s State University of Culture and Art. As he tells it, in 1994 he had a group of students with whom he had a rocky relationship - they were dedicated but there was friction over issues of leadership and initiative. The students acted out their frustrations, which led their teacher to return next day with the basis of The Drummers - a play which is still in the repertoire and which was a prize-winner in Holland.

The studentswould not give up or go away and the Crowd of Fools Pantomime studio theatre was set up, in 1994.

Another of Pantomime´s most popular sketches, The Drummers, features a group of naghara players who rebel against their leader. There are no drums; the characters communicate by voicing the sounds of the naghara to enact the most ferocious, and hilarious, battles for leadership. The body language and sounds somehow put the words they are not saying directly into your brain, in whatever language you like. There is no hiding place from the idiocies of energy expended on the games of status we play in our lives.

The power of wordless suggestion continues to amaze. Actor Elman Rafiyev - offstage a one man verbal Niagara - recalls how, after a performance of The Violinists, a member of the audience congratulated the director on his actors´ accomplished playing.

The Violinists, as you´d expect by now, involves not a single violin, but the mesmerising enthusiasm of the actors persuades you into a ´live´ performance of the soundtrack. The performance includes a dramatic appearance by a venerable maestro, summoning reserves of energy from who knows what source deep within.

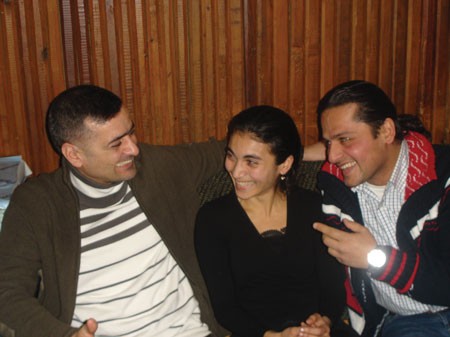

Discussion with the actors reveals a range of origins and motivations, but a common need to do this thing called acting: Elman was one of the original University group from whom Bakhtiyar muallim was unable to escape - once Elman had overcome his parents´ reservations about the life of an actor. Qurban Masimov was not in the same group at University - he was studying directing - again because his parents were unhappy about their son going on stage. But his curiosity led him to hang around, listening in to the acting group at work, until he was finally invited in. Nargila Qaribova was invited to join a couple ofyears later - after also convincing reluctant parents and leaving other teachers who were not so convinced of her talent - and she clearly revels in a medium which allows her to take on a very different persona, with much freer expression than in ´real´ life: she grows visibly as soon as she steps on an area designated a stage.

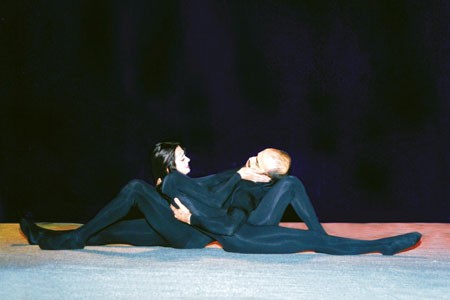

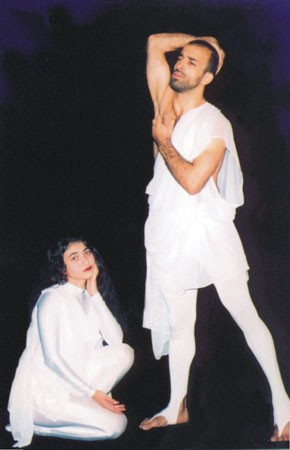

The comedy of the Pantomime Theatre may be its best known work, but tragedy and pathos are also to the fore as boundaries of expression are pushed back in, for example, The Mask. Mask work is viewed with trepidation in some circles, as the ´personality´ of the mask takes the actor into realms previously unexplored (a phenomenon used to comic effect in Hollywood by Jim Carrey among others). The Pantomime Theatre´s play takes the story of the ´good-time girl´ who finds love but who is trapped in the image allotted her by social convention. Attempting to break out of this pigeonhole she is met by a violent assertion of society´s mores. The piece is an urgent exploration of the conflict between individuality and conformity, understanding and morality. Its unashamed use of highly emotional and physical expression - delivered with knife-edge intensity, especially by Qaribova as the girl - leaves the audience in some turmoil by the end. It takes a few seconds before ´here and now´ returns and the actors are applauded for a stunning performance.

Other, more lyrical, aspects of love appear in adaptations of Fizuli´s Leyli and Majnun (A Slave to Sadness) and Shakespeare´s sonnets (Love), the latter cleverly and effectively using Shakespearean images (the moon and stars, adjoining pages in a book, ink and paper) to contemplate the life, death and rebirth of love in its different forms.

These more serious works are better described as drama by movement than as dance. Dance is certainly there, but so are elements of mime and something eastern, as evidenced by the director´s interest in the movement in martial arts.

Perhaps the darkest piece of work is The Ladder, in which three associates combine to form a triumvirate on a podium of power, only for naked ambition to take hold, leading inevitably to the meanest standing alone - very alone - at the top. The menace is in movement to a bureaucratic rhythm as rigid and bloodless as the shabby, white-faced forms of the comrade contenders. A simple gesture, such as the flicking of a finger to indicate time passing, becomes an intimidating countdown to disaster. The appearance of a cheeky character at the end presents a ray of hope – the gleam in his eye sending a shudder through the dictator clinging desperately to his status.

The commitment, and resulting work-rate, of the Pantomime Theatre actors is astonishing, as the actors tell us:

´Bakhtiyar muallim wants to develop universal students - who want to do everything´...´No one in the audience should be able to say "I could do that"´...´Wehave to do everything´...

Thus Elman is theatre MC and music researcher as well as actor in a variety of roles, Qurban is the clown operator of The Vocalist - an operatic singer created from the clown´s gloved hands and a pair of sunglasses, who manages to be both comic and emotional. He´s also the theatre´s designer...and he devised the mugham trio. Nargila is a lithe, lovelorn Leyli, alternately hard-nosed and suffering in The Mask, and has also begun to devise plays. We should mention Parviz Mammadrzayev who, when not teaching at the Culture and Art University, is a dancing Majnun, tar ´player´ in the mugham trio, tyrannical leader of The Drummers and a one-man United Nations in The Potter – Uzeyir Hajibayov´s gentle nudge at his own nation. We watched a DVD of performances prior to writing this and commented on Parviz´ beautifully moving performance in what is, apparently, a mime ´standard´ called Separation, in which he duets with a hat stand. It was immediately inserted into the weekend´s performance; such is the commitment and flexibility of this theatre - and its relationship to its audience.

We asked Bakhtiyar Khani-zada about the future, but he would not answer, because ´I do not want God to laugh at me.´ We suspect, however that the only laughter from above will be at comedic moments in the very life-affirming Azerbaijan State Pantomime Theatre.

Mime - a Way Without Words

37240

0 COMMENTS

Only logged in users can leave comments

Login Registration