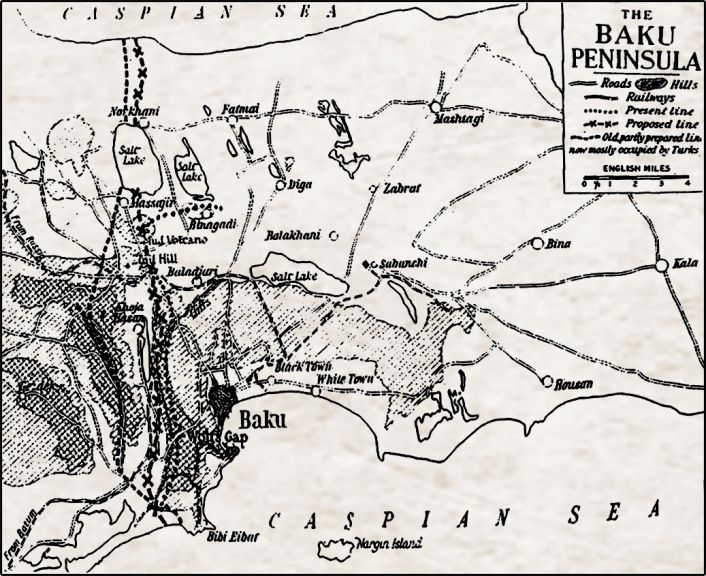

This is the second of a two-part article on Azerbaijan in 1918, at the end of the First World War. The first part (‘1918: Azerbaijan at War,’ July-August 2015 issue of Visions) looked at the situation in Azerbaijan at the start of 1918 and the strategic thinking behind the British decision to send an expeditionary force to prevent Baku falling into the hands of advancing Ottoman forces. This second part examines life for the soldiers and the local people in Baku, under siege by Ottoman forces in the summer of 1918. It concludes with an assessment of whether the British strategy of defending Baku against the Ottomans was a success or failure.

A falling out among allies

Although by the end of July 1918, Baku looked as though it was about to fall to the Ottoman besieging force, the Ottomans had their own problems. They had suffered badly in the war. Their soldiers were demoralised, badly equipped, underfed and poorly led. Added to all that, a treaty between Georgia and Germany led the Ottomans into open conflict with their allies. In June, German forces exchanged fire with Ottoman troops and the Germans threatened to withdraw all military assistance from their Turkish allies.

The Ottoman discord with Germany became so acute that in August, Germany, which had not recognised Azerbaijan’s independence, entered into a secret treaty with Russia. The terms of the treaty were reported in a British Foreign Office memorandum thus: Russia will do her utmost to further the production of crude oil and crude-oil products in the Baku district, and will supply to Germany a quarter of the amount produced, and Germany would take measures to prevent the Ottomans overstepping certain defined boundaries in the Caucasus.

That Baku did not fall in July was in part due to the weakness of the Ottoman forces and to the lack of support, even obstruction, from their German allies.

Life in Baku after the ousting of the Bolsheviks

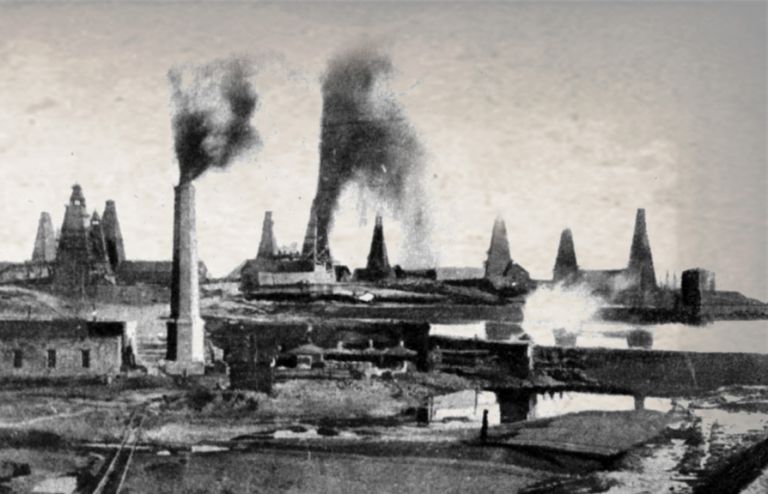

The situation in Baku was dire even before the newly formed Ottoman Caucasian Army of Islam began its encirclement in late July 1918. The Bolsheviks had nationalised the oil industry, the banks, larger businesses and the Caspian fleet. That dramatically cut the amount of trade and, consequently, the import of foodstuffs. Baku was fast running out of food and hoarding of food and money was adding to its problems. The siege merely made matters worse as the only way to bring food into the city was now by sea. The food crisis, and a determination not to be party to either a surrender of the city to the Turks or an alliance with the British, caused the Bolsheviks to relinquish power.

Baku was fast running our of food and hoarding of food and money was adding to its problems

In The Adventures of Dunsterforce, Brigadier-General Dunsterville, the man in overall command of the British expeditionary force to Baku, quoted from a letter sent in mid-August from Baku by Colonel Keyworth. This summed up the food situation as becoming acute. It seems Baku has imported nothing for two months and that they have only a week’s supply left. The workers in the oilfields are being starved; the price of food augments daily.

Dunsterville also tells us that the horse trams that used to run in the city had stopped due to the shortage of fodder for the animals. The food shortages meant that what food was available was expensive. Dunsterville found himself paying at the Metropole Hotel about £2 for a dinner of soup, fish, joint and watermelon, with bread. A British officer’s allowance for board and lodging was £1 per day.

Dunsterville used the example of watermelons to explain the food situation. Why, he pondered, were watermelons fifteen times more expensive in Baku than in Enzeli, when Enzeli, a Persian Caspian port, was only eighteen hours’ steam away? The answer, he said, was because the shipping was nationalized, which means that all private enterprise was dead. The exception was -

[s]hips, such as my transports, … [when] ordered to Enzeli on duty. Before leaving on the return journey the crew clubbed together and purchased watermelons, stacking them in the hold and on the decks, till nothing was visible but a green mound of melons. On the arrival of the ship in Baku a queue of intending purchasers was formed from the ship’s side along the pier, out on the quay and up the adjoining streets ...

So keen were the sailors to profit from the arbitrage opportunities that on one occasion, because there was a shortage of melons on the Enzeli market, one of Dunsterville’s transports from Enzeli refused to leave as scheduled until more melons could be had.

Being a city under siege, Baku had to suffer more than food shortages. There was sporadic shelling from Turkish guns, more pronounced preceding a major attack, though until the final assault on 14 September there seems to have been no substantial damage. Dunsterville wrote:

[Baku] was rather heavily shelled on the night of [23 August], terrifying the unfortunate inhabitants, but causing very little loss of life and doing us in a general way much good, by reminding them that the Turk was at the door. Whenever the shelling ceased for a day, the townspeople relaxed their efforts under the impression that the danger was not so imminent.

Indeed, as a sign of the Baku populace being blind to reality, on 28 August elections for the Baku soviet were held and almost 11,000 people voted (according to Ronald G. Suny in The Baku Commune 1917-1918). So relaxed were they, wrote Dunsterville, that the inhabitants are getting accustomed to [the shelling]. The small shells, he added, do very little harm ... and the sickly swains and their haughty little girls continue their nightly promenade undisturbed.

No attempt was made even to dim the lights at night to make the Turkish targeting of the town more difficult, for the townsfolk were all promenading every evening on the boulevards by the electric light.

When the Turks attacked on 26 August, causing the British to retreat from some strategic positions with heavy casualties, panic started to set in, especially among the Armenians of Baku.

Steamers, wrote Dunsterville, were now leaving daily for Krasnovodsk [Turkmenbashi] crowded with refugees wisely escaping from the wrath to come. Rather like the shelling, that too had its advantages as, any reduction in the civil population [helped] very much to simplify the supply question.

Other than at the front line, conditions for the soldiers also seemed quite relaxed. Rations consisted of coarse dark brown bread made with sour dough, Lieutenant Missen recalled in a BBC radio interview, and the tea was made with oily well-water (the Ottomans having cut the main water supply). Meat was a regular part of the diet and, if unavailable, salt fish was substituted. Caviar was plentiful but the British troops disparagingly referred to it as herring paste. A substantial number of troops were falling ill to tummy troubles as Missen recalled, particularly on the front-line where conditions were less sanitary than in Baku.

Still, according to Dunsterville the troops never suffered from a shortage of good wholesome meat and bread, but vegetables, jam, butter and milk were unobtainable. I was lucky getting some splendid honey from Enzeli, and the men were once or twice cheered by an issue of Baku beer.

That was a feast compared to what the Turkish soldiers had to eat – by September their meat ration had stopped and they were surviving on a little soup twice daily of flour and water [and] an issue of crushed barley daily (British National Archives, WO95/5157/56, 13 September 1918).

Money troubles

In addition to food shortages for the townsfolk, there was also a scarcity of money. There were three types of currency in circulation: the old imperial roubles, the Kerensky early revolutionary Russian government roubles and the bonds printed by the Baku government. The unofficial exchange rates varied considerably, the imperial rouble being the most sought after and the Baku bond accepted only in small transactions.

The nationalisation of the banks by the Bolsheviks had been accompanied by a freezing of accounts, with depositors only being permitted to withdraw 300 roubles per month. Nationalisation resulted in the banks losing their experienced staff whilst causing a collapse in confidence in the banking system. The natural consequence was that the circulation of cash dried up, which further depressed trade. The British tried to restore confidence in the banks, encouraging the freeing-up of depositors’ accounts and free enterprise though there is little indication that they succeeded.

To try and keep money in circulation, local Baku bonds were issued by the Baku government, initially secured on town property but later printed without any asset backing. The bond, unlike the imperial and Kerensky rouble, was not accepted outside Baku, consequently unsecured bonds became almost worthless as the crisis in Baku deepened. Still, as roubles were scarce, British purchases were often paid for in Baku bonds.

Dunsterforce carried with it sizeable quantities of British pounds sterling and silver Persian krans. These had to be converted to a local currency so they could pay for food and other provisions, such as the 500 goggles Dunsterforce purchased at the end of August to prevent against sandstorms. The krans were more tradable than the pounds, which not everyone wanted or had the cash to buy in large enough quantities. About eight million roubles were acquired through the sale of krans.

Foreigners in Baku

The advance party of Dunsterforce arrived in Baku on 4 August 1918 (40 men of the Hampshire Regiment led by Dunsterville’s chief intelligence officer, Lt.-Colonel Stokes). The early arrivals were greeted by a band at the pier. They were, after all, going to be the saviours of Baku. On 6 August, they were even serenaded in their billets by two or three hundred mounted Russians with a brass band playing the Marseillaise.

Although the backstreets were unsafe after dark, life for Dunsterforce officers seems not to have been too uncomfortable. Billets were obtained in the two grandest hotels of the city, the Hotel d’Europe and the nearby Metropole (today, the Nizami Museum). The Hotel d’Europe was where the headquarters of the 39th Brigade were first located, though later forced by shelling to shift to the Metropole. Both hotels were well appointed, with, as Dunsterville describes them, gilt furniture and crimson plush curtains offending the eye at every turn.

Most of the British soldiers were not billeted in the hotels but in schools – the North Staffords, together with the military hospital, in the Tartar Girls’ School and the small detachment of the Hampshires and the more numerous 9th Battalion Worcestershire Regiment were put up in the Tartar Boys’ School next door. These schools are today the Institute of Manuscripts and the Economic University respectively.

Dunsterville himself kept his general staff headquarters on board the SS President Kruger. Shelling caused him to move the ship to the old customs house wharf, which was also where the British arsenal was located, not far from today’s Four Seasons Hotel.

Baku was essentially run by Armenians and Russians, though the town also had Tartar inhabitants (Azerbaijanis, Persians etc.) and an assortment of Caucasians. Dunsterville, a consummate diplomat, tried hard not to alienate any particular group as long as they could prove useful. He wrote that he,

had an interesting meeting with one of the leading Tartars, a very intelligent and highly educated man, but if I were known to be entering into any sort of relations with these excellent people the town would have been in an uproar, so … I had to go at dead of night … to a house in the Tartar quarter of the town.

The British troops were not the only ‘‘Westerners’’ in Baku. There were small communities of British, Americans, French, Belgians, Greeks and others. These included diplomats, intelligence officers, businessmen, oil engineers and the like. The British consul at Resht was transferred to Baku, together with a bevy of attractive Russian stenographers. In addition there were the German and Turkish prisoners of war released following the signing of the Brest-Litovsk treaty between the Central Powers and Russia (remarkably, German officers turned up on 4 August expecting the town to be in Turkish hands only to find themselves taken prisoner).

Baku falls & Dunsterforce withdraws

The Caucasian Army of Islam’s final assault on 14 September caused a hasty but orderly withdrawal of Dunsterforce. Thus, Dunsterville finally obeyed an order to withdraw which he had received almost two weeks previously.

The attackers included both regular and irregular troops. Judging by the names on the Turkish monument to the Ottoman war casualties of the Caucasus campaign at today’s Alley of Martyrs in Baku, about 15 per cent of those who died in fighting in the Caucasus were Azerbaijanis. Assuming the monument accounts only for regular troops, one can conclude that a substantial proportion of the total besieging force was made up of Azerbaijanis, as the irregulars, commanded by Turkish officers, were about equal in number to the regular forces, and were comprised of Caucasian Muslim levies – including Azerbaijanis, Daghestanis, Lezghis etc.

As for Dunsterforce, by Dunsterville’s own reckoning, he had done excellent work under trying conditions, and produced very good results out of nothing. Most accounts record that a small heroic British force staved off a vastly superior Turkish one for a critical six-week period and that Dunsterforce might have succeeded altogether in preventing Baku falling if he had been given more troops and if there had been effective support from the local defenders, who were politicised, shambolic and largely disinclined to fight.

In fact, although the besieging Caucasus Army of Islam outnumbered the defenders, it was hardly overwhelming and it was certainly outgunned by the defenders. The defenders had armoured cars, an armoured train, gunboats and aeroplanes, none of which the besieging force had. The defenders also possessed more and better artillery and machine guns.

Despite these advantages, Dunsterville failed to keep the Turks out of Baku or to destroy the oilfields or to take control of all the shipping on the Caspian. He had not met any of his objectives. For a military commander, that must be recorded as a failure. Moreover, he had not been present in Baku at a critical moment and failed to take proper control of the situation. In this he was hampered by the politics of the situation as well as the mixed signals he had been getting from his superiors concerning strategy. [In] spite of apathy and misunderstanding of War Office and Baghdad, Dunsterville accepted that they had no course to relieve me and to try me, I suppose by Court Martial.

That surely was not the expectation of a commander who believed he had been successful in the field. Admittedly, even a better commander would have found the situation challenging and Dunsterville did skilfully manage to extricate the bulk of his force from Baku. Overall British casualties (killed, wounded or missing) amounted to at least 330 officers and other ranks, or just under 30 per cent of the total force. Of these, about 60 men and 2 officers were taken prisoner.

In the end, Dunsterville was not court-martialled but General Marshall, his commanding officer, thought Dunsterville too much of a Don Quixote (as quoted in Keith Jeffery’s Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson) and had no misgivings about Dunsterville’s loss of command upon his return to Enzeli.

Colonel Warden, Dunsterville’s Inspector of Infantry, in his diary gave the one discordant contemporary view. He believed, Baku could have been held by good sound management [and] organization but Gen. Dunsterville was not capable of doing either and, he added, his staff officers were far worse.

About the author: Alum Bati is a barrister and long-time resident of Baku. He is also the author of Harem Secrets and Caravan to Paradise, a pair of historical thrillers set in 16th century Istanbul.