It all started with the question Grandma, what’s this? From here the boy began to fall in love with felt, to explore and put his signature on a new trend in the world of painting, and perhaps this was even one of the most challenging and innovative signatures in modern Azerbaijani painting.

My interviewee is Rauf Ismayilov - the first and leading felt painter in Azerbaijan. He shares his experience with me at his workplace, or as he calls it, his second home.

Rauf was born in 1957, in the city of Mingachevir, 311km from the capital of Azerbaijan, Baku. He began painting when he was just three years old and thanks to his father, this interest grew:

My father always wanted to become a painter, however because of the Second World War, his dream never came true, everything remained unfinished.

The painter’s father, Abdulhuseyn, was honoured for his services to improving the city. At the same time he was a member of the Supreme Council of Azerbaijan during the Soviet period. As part of his job, Rauf’s father travelled to Moscow very often. Each time he returned home, he brought twelve colouring pencils for little Rauf: In Soviet times you couldn’t find things like colouring pencils easily, he recalled.

Rauf believes a parent should always push their child to make their dreams come true but be careful not to ruin them:

I had such great support from my father, even when I painted spontaneously he always gave useful advice very patiently. He didn’t have any education in painting, but he had a very good eye for looking [at my work].

Rauf Ismayilov received his first painting classes during the Soviet period from German POW painters, who had been sent to Mingachevir following World War II (Mingachevir and the Mingachevir hydroelectric station were built following the war by a joint workforce of some 10,000 German POWs and 5,000 locals - Ed). Again, it was his father that had introduced him to them. As one of the founders of Mingachevir, Abdulhuseyn had many Russian friends, one of whom was a man called Aleksandr Ivanov.

‘‘You will be a painter”

Aleksandr Ivanov, or as Rauf called him - Dyadya Sasha (Uncle Sasha) was a painter who had come to Mingachevir from the Kalmykia region of Russia. According to Rauf, like the German POWs, uncle Sasha was also involved in building the city:

I was five years old when my father took me to see uncle Sasha for the first time. I brought my paintings as well. Ivanov looked at my works and quickly said: You will be a painter. He smoked a lot, so he threw a matchbox on the table and asked me to paint it. I was a small child and I had never painted anything like this, but somehow I managed to do it. He said there had to be some focus, so my father decided to take me there twice a week.

In other words, Rauf grew up in a family with a great interest in art. His father was an amateur piano player, and his mother was awarded the title of Hero Mother as she had ten children (the title was awarded in Soviet times to mothers raising 10 or more children, along with receiving certain privileges such as higher pensions and extra food supplies – Ed.). Rauf was one of those ten, all of whom received a university education except for one who graduated from college.

He smoked a lot, so he threw a matchbox on the table and asked me to paint it

The painter is very proud to be the son of a Hero Mother. Sharing memories of her he reminisces about the time she met the late president of Azerbaijan, Heydar Aliyev, in Mingachevir:

When Heydar Aliyev visited Mingachevir, my mother was among those who came to greet him. Since she was an Honoured Worker, Heydar Aliyev had a proper conversation with her for around fifteen minutes. He heard how this woman lived in a 23 square metre small house with her ten children and instructed that we be moved to a house in the city centre. He deeply valued the hard workers and the intellectuals of his country.

Learning the basics

Rauf’s next teacher was a Swedish-born German called Anderson. After World War II he was sent to Mingachevir as a POW; he worked at the Drama Theatre and at the same time gave painting classes at the Pioneers’ House. The ten-year-old Rauf became his student for some time, but then felt Anderson’s method of teaching wasn’t quite right:

I always want to do something impossible in life, I want to explore what doesn’t yet exist

Anderson showed us the works of very well known painters and then told us to copy them. I had to do oil painting without learning the basics of this type of art - that was wrong. Of course, at that time I was so happy that I worked on canvas anyway.

Later Rauf used to say to his students at the Azerbaijan State University of Culture and Art that they should learn the first letter in their profession in order to then progress to oil paintings. To study the basics of painting he was admitted to the Azim Azimzada State Art School, and in 1980 he graduated from there with distinction. He then continued his education in Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg) and after graduating from there he entered the University of Culture and Art in Baku. He wanted to learn carpet weaving and became a student of Latif Karimov, a legendary Azerbaijani carpet artist.

To fall in love with felt

Rauf Ismayilov’s family originally came from the Azerbaijani region of Shirvan and when he was a child he used to visit his grandparents, who lived in Zardab in central Azerbaijan, a district 231km to the west of Baku.

There, houses were built from baked brick, then plastered with mud from the inside and out. These houses were very cool, so people living there used to have felt carpets. The 10-year-old Rauf once noticed the felt under his feet and asked his grandmother what this was:

My grandmother said, “it’s felt, my son.” This word then stuck in my mind. I always want to do something impossible in life, I want to explore what doesn’t yet exist. Therefore, I started to look into what this was, and my research lasted for more than 10 years.

Rauf also talks about the history of felt. If you remember, he tells me, felt was also mentioned in the Book of Dede Gorgud (the Oghuz epic poem). Nomads built their tents from felt as it kept their tents cool in summer and hot in winter. In such a way Turkish people used felt for their personal welfare - as carpets, felt cloaks for shepherds, saddles for horses and special felt was used for doors.

Then I realised that the history of felt dates back to ancient times (to the 1st millennium BC), it belongs to Turkish people

The painter describes those examples as primitive, because they weren’t made by professional artists:

Then I realised that the history of felt dates back to ancient times (to the 1st millenium BC), it belongs to Turkish people - a horned tiger felt carpet found in the Tuket burial mound is proof of that. So felt existed before carpets or rugs. Also, you can find examples of felt work in other places where Turkish people used to live, such as Georgia and Ukraine.

He also mentions some very interesting historical facts regarding felt. Very few people know that the Qur’an contains information about felt (in the 72nd chapter, 19th verse). Moreover, he says that under the Hun ruler Atilla soldiers used felt as underwear before going to fight the enemy because it absorbed sweat and moisture. Similarly, during the time of Soltan Ahmad Shah Qajar, his soldiers used felt to cover horses’ feet before going into battle, so they weren’t sucked into swamps.

How felt turns into art

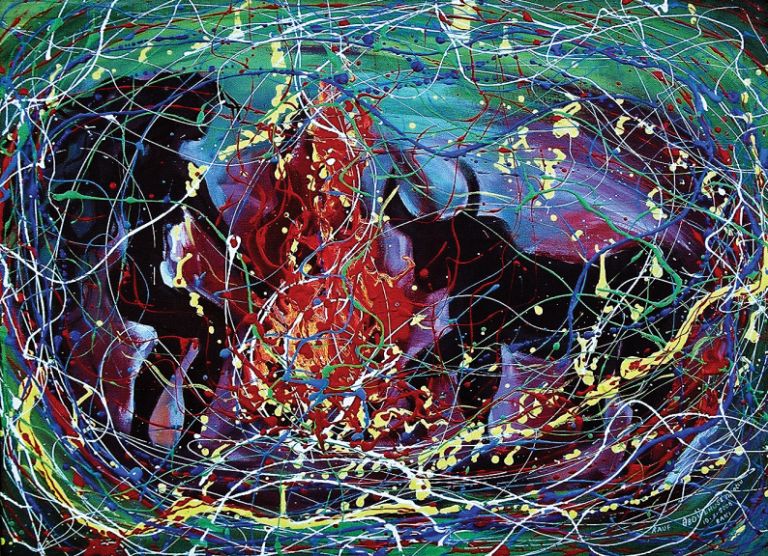

25 years ago Rauf decided to start creating works of art from felt. He describes the process and technology involved in this:

Firstly, I bought wool; it was very hard to make it thinner. I used artificial colours at that time.

According to Rauf, the wool has to be taken from sheep and then brushed. Then you paint it with colour, then you wash and brush it again. Then the painter sketches onto cardboard, and only then he starts to work with the felt. Rauf is now a professional, so he doesn’t need to sketch, everything is in his mind. He also makes original colours himself; green from fig leaves; red from blackberries; brown from walnut trees etc. He loves black most of all:

There is love and life, sadness and death in this colour; black has both hot and cold colours within it.

In his 13-square-metre studio Rauf had a rich selection of paintings. He didn’t like to talk excessively about his awards, but agreed to name a few, such as the Humay National Award, the Soltan Mohammed Award, and the Painters’ Union of Azerbaijan Award. He also has plenty of diplomas demonstrating his success.

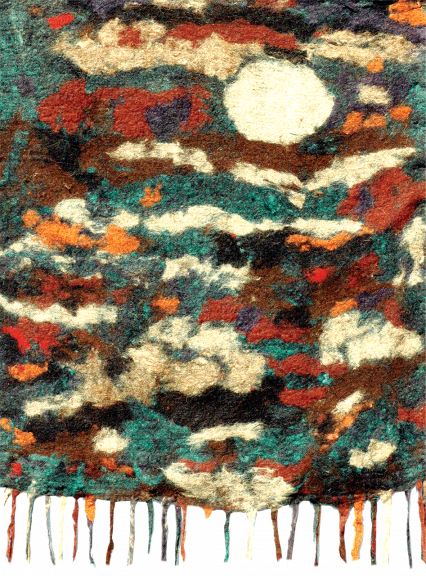

“Let There Always Be Sunshine”

His first painting using felt was called Let There Always Be Sunshine. By giving the painting this name he hoped to send a message of peace and prosperity in the world, but he also wanted his work with felt to always reflect sunshine. He couldn’t exhibit his first painting in Azerbaijan because no one accepted this new style of art, but then he was invited to an exhibition in the city of Novgorod in Russia, and there his work generated great interest for the first time.

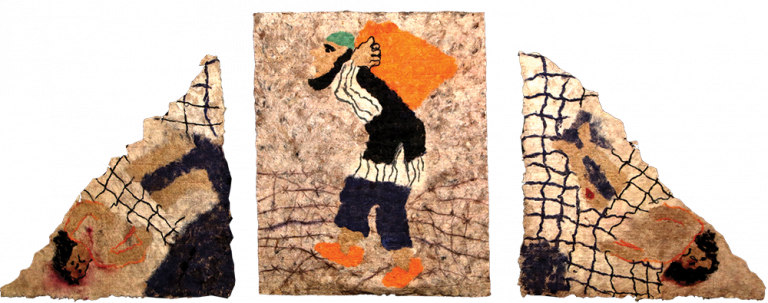

His second work, called Karvan, was sold in an exhibition in Baku. The Azerbaijani Ministry of Culture bought it, which was a great motivator for the young painter who wanted to be accepted with his felt art.

There is love and life, sadness and death in this colour; black has both hot and cold colours within it

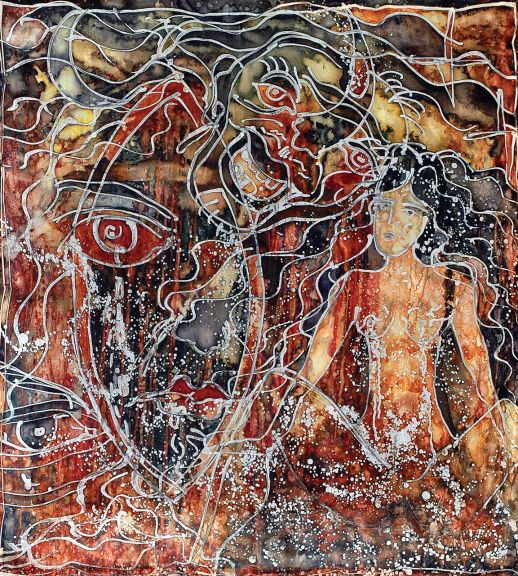

Rauf has now had four exhibitions in Baku, two of them were individual, the others were with his son and only student, also called Abdulhuseyn:

I also had an individual exhibition in Turkey, the Netherlands (my felt works are kept in a museum permanently there, the USA and Russia. I had a group exhibition in France, where my felt art seemed very unique and modern to foreign visitors.

He counts the fact that his paintings are accepted in the world as his main success. In 1991 the UN ex-secretary general, Mr Boutros Boutros-Ghali, visited Baku. Rauf’s felt work entitled Karabakh Songs was given to him as a present, and this piece still remains at the UN’s main exhibition hall in New York. The painter’s future plans regarding his felt art are also interesting. Rauf is planning to combine felt with interior design and he is also thinking about making dresses with national ornaments.

About the author: Sabina Izzatli graduated from the Faculty of Journalism at Baku State University and has contributed to the Institute for War and Peace Reporting, BBC Media Action, among other publications.