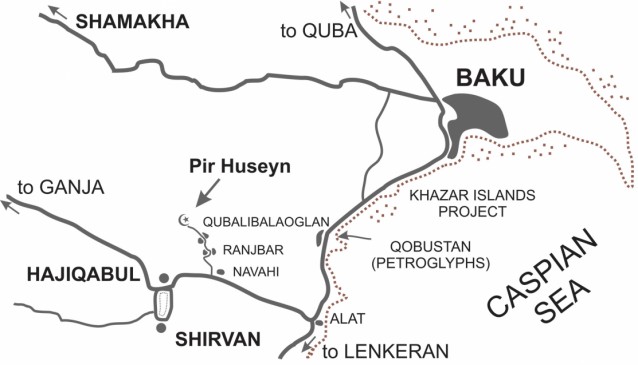

For a tourist heading south out of Baku for the day, the main attractions tend to be the ever-bubbling little mud volcanoes above Alat and the famous petroglyphs at Qobustan. The latter now has a splendid new museum and on a nearby hill, a curious Noah’s Ark appears to have landed during 2014. These sites are around an hour’s drive south of Baku on the smooth Ganja-bound highway which swings west after Alat. But if you drive a little further, there’s a far lesser known site hidden away 18km off the highway behind Qubali Baloghlan: the charming little shrine-caravanserai complex of Pir Huseyn.

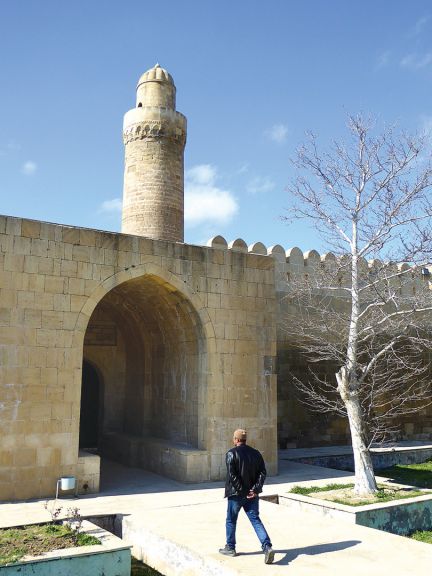

Today the most obvious feature is a classic minaret in the typical Old-Baku style, protruding from a compound protected by two-storey stone walls reinforced by semi-circular mock-towers and topped with battlements. The crenulations were mostly added in a 2007 rebuild but the minaret and other core architectual elements date from the 13th century or earlier. The day I arrived I was the only tourist – indeed the first for several weeks judging from the visitors’ book whose entries stretched back nearly a decade. The peaceful site sits in a lonely spot backed slightly incongruously by a dam across the Pirsaat River. A stairway leads up to the dam’s lip, well worth climbing for a fine overview of the complex and of the buff and dun hillsides undulating in waves towards the northern horizon behind the shimmering blue reservoir.

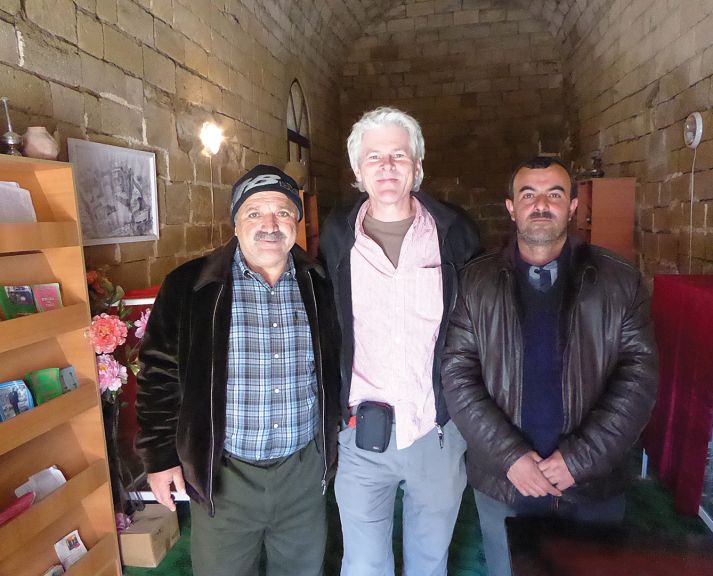

The Guardian Angels

Puffing up the steps behind me came Vagif Azizov, an enthusiastic 60-year-old guide to the site. Having only started here two months previously, his main role seems to be that of translating into Russian the wider historical and spiritual insights of Molla Mehdikhan Baghiyev and his brother Hasanagha, the spiritual guardians of the place. Mehdikhan radiates at once a sense of warm welcome and meditative calm with a cheeky sense of playfulness – smoking on ultra-thin cigarettes and playing me the Muezzin’s Allahu Akbar cry on his mobile phone. I’d come at a good time, they assured me. In summer the peace and quiet of this place would apparently be shattered by crowds of the faithful coming to the site to gain spiritual merit or superstitious luck by a series of prayers... and possibly an animal sacrifice.

Huseyn Who?

As always with such places, there are various, often contradictory, versions of its history. By one of these1, the Huseyn for which the revered shrine is named was Huseyn Ravani, a Sufi mystic born in AD954 and reputedly living for almost 120 years. He was also known as ‘Shirvani Sagir’ (The Junior Shirvani), the ‘junior’ being in comparison to his better known older brother, great Sufi philosopher-poet ‘Senior Shirvani’ Muhammad Bakuvi (aka Baba Kuhi, 948-1050) who was buried in Tabriz.

It appears that Huseyn’s grave was built into what had already been an existing khanegar (sufi hermitage-style retreat) during his lifetime. If this was indeed the case, Pir Huseyn then represents one of the oldest such establishments recorded in Azerbaijan. The presence of his tomb here initially drew so many pilgrims that the complex developed a huge wakuf (endowment fund) with which to maintain and embellish the place. The buildings reached their most ornate states in the 13th century, with the minaret originally added in 1256 during the reign of Shirvanshah Akhsitan II and embellished after 1284. A grand freize of carved Arabic inscription, once thought to have been set across the main gateway, is dated 1243-44.

Mehdikhan radiates at once a sense of warm welcome and meditative calm with a cheeky sense of playfulness – smoking on ultra-thin cigarettes and playing me the Muezzin’s Allahu Akbar cry on his mobile phone

Inscriptions suggest that significant repairs to the khaneghah complex were undertaken in 1420 while archaeologists suspect that a now demolished octagonal mausoleum tower was added around the same time. There appears to have been a further renovation in 1639. A secular building, whose modest ruins lie just outside of the main walled compound, once functioned as a caravanserai on the Tabriz-Shamakha route, and may date from this era. During the later 17th century there seems to have been little new building and the site lay largely unnoticed for decades.

Finally Pir Huseyn was ‘rediscovered’ in 1858 by Ivan Bartolomey (1813-1870). A Russian Lieutenant-General of Ciracassian descent, Bartolemey had been sent to the Caucasus on military service. Wounded in Chechnya he later took on the perilous mission of trying to make peace between Russia and Svaneti (in today’s Georgia). But in the meanwhile he spent most of his spare time seeking out ancient sites and expanding his prized coin collecton.

Peeping Inside

Today the surviving panels of the 1244 frieze are the most visually impressive articles displayed within a timeless little museum-room that also houses a selection of archaeological finds. At the back of the shrine-approach chamber is the tomb of one of Huseyn’s loyal disciples covered with a green cloth. On top of that lie three rough if hand-worn hunks of rock, each around half the size of a bowling ball.

Go on, pick one up! chuckles Molla Mehdikhan, seeing that I’m inquisitive as to their presence here. I grab one whose side has been sliced almost flat and realise a bit too late that it’s far far heavier than it looks. It slips from my hand and I laugh in slightly embarassed amusement. Much heavier than it looks, huh?

The exact story of what makes these stones so dense rather passes over my head and bruised fingers as we peep into the inner sanctum behind. The actual grave chamber of Huseyn. I hold my breath with anticipation. After all this place has a considerable historical reputation...

A little more history

The shrine chamber today is entirely unembellished, a sad discovery though perhaps that’s much more what a Sufi saint would have hoped for

On arriving here in 1858, Bartolemey found that behind a ruinous exterior, the khaneghah shrine’s interior had survived joyously intact, retaining one of the most stunning interiors he’d seen in years of amateur archaeology. He tipped off Russo-German orientalist Johannes (‘Boris’) Dorn (1805-1881) who arrived here on horseback in 1861, gushing at the sense of timelessness that the complex then projected. Dorn agreed that the shrine room interior was a masterpiece and set about recording and cataloguing the inscriptions. Most notable were the ceiling mouldings and the mihrab (Qibla-niche indicating the direction of Mecca) which retained dazzling glazed brickwork dated AH665 (1266-67AD) and referenced the then-reigning Shirvanshah, Farukhzad II.

None of this remains. The shrine chamber today is entirely unembellished, a sad discovery though perhaps that’s much more what a Sufi saint would have hoped for. Over the centuries, it seems, the decorative bricks and inscription panels were gradually removed. Collectors have sent some as far afield as the Louvre in Paris and the Hermitage in St Petersburg. In 1940 the fragmentary remnants were surveyed and what was left of the glazed mihrab was shipped out – by one report it is now housed in the Nizami Literature Museum.

Not in that vehicle, says Molla Mehdikhan indicating with some contempt my far-too-urban car. But come back with a Niva and you should be OK. I can’t wait to try.

|

Practicalities - finding Pir Huseyn Khaneghah:

From the main Baku-Ganja highway, turn north (right) at Km102.6 on an easily missed asphalt road beside the Ipek Yolu Restaurant. The access lane to Pir Huseyn is now well surfaced all the way, dead-ending after nearly 18km at the shrine gates, albeit wiggling through the villages of Randzhbar and Qubali Baloghlan en route. You’ll drive very close to a super-tall TV transmission tower that’s visible for miles around. Coming from the west is more challenging. Despite a clear sign on the Ganja-Baku carriageway, there’s no turning point off the motorway so you have two choices. First is to continue to the DYP /YPX post at Km402.6/100.4 and nip through the small gap - locals do this and I have too, but it’s always unnerving to stop, even willingly, at a traffic cop station. The longer alternative is continuing to the bigger U-turn gap before Navahi at Km404.2/98.8.

To return to Baku from Pir Huseyn you’ll first need to head west then find the U-turn gap at Km105.7/397.5. Watch carefully - if you miss it you’ll probably have to drive all the way to Hajiqabul. If you don’t have your own wheels, there are three public buses a day (80q) departing from the market in Hajiqabul at 9am, 11am and 3pm but running only as far as Qubali Baloghlan from which they return an hour or so later. From Qubali Baloghlan you’ll need to ask around for an informal taxi to drive the last 10km to the shrine – expect to pay about 10AZN return including waiting. |