Sometimes, we don’t know the true value of the moment, until it becomes a memory...

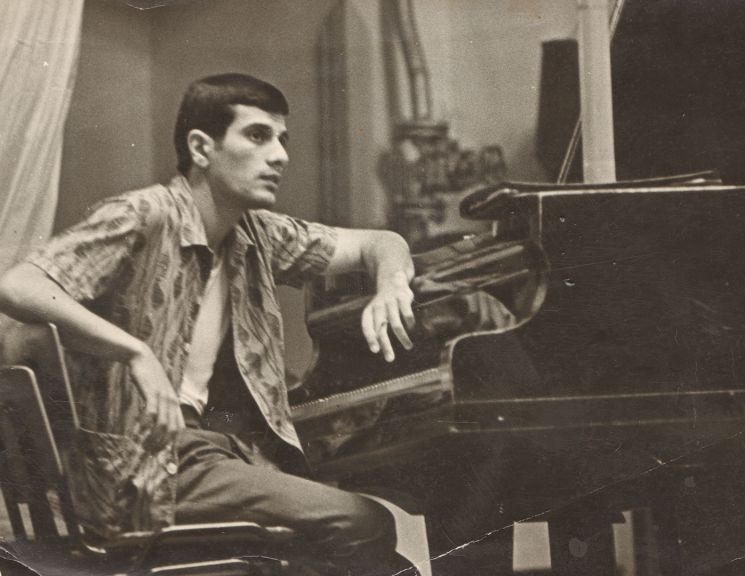

Sitting back in his favourite chair, he turns to the window and it seems like the year 2015 dissolves as he goes back to some distant memory, through the line of events that brought us here. Music, in all its forms, has been the main interest throughout my grandfather’s life. Along with the grand piano, he learned the essentials of playing cello, contrabass and drums - all before the official start of his career.

It came in handy in various situations in my concert life later on. No kidding.

Add the vibraphone, pipe organ, synthesizer and accordion to the list of instruments he unofficially plays.

Well, accordion doesn’t really count: the keyboard there is the same, he clarifies.

After being drafted into the army in Feodosiya [in the Crimea - Ed], he immediately joined the local orchestra. When musical bands were in town, he and other newly conscripted musicians would play jazz jam sessions before and after concerts.

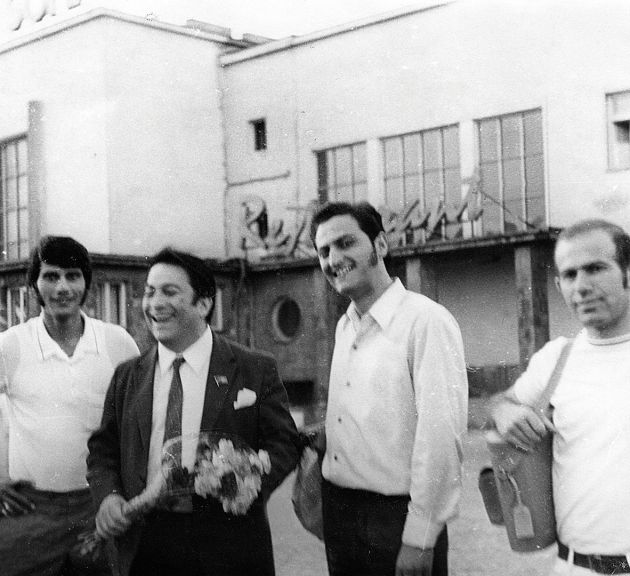

In 1968, back in Baku, he organised the Sevgilim ensemble in the Azerbaijan State Philharmonia while still playing and composing jazz at the same time, with three other musicians. This was followed by collaborations with the Gunib ensemble in Dagestan and the Dielo ensemble in Georgia and eventually, in 1970, he was on a final solo trip to Kemerovo, where an invitation came from Rashid Behbudov to work in the Song Theatre.

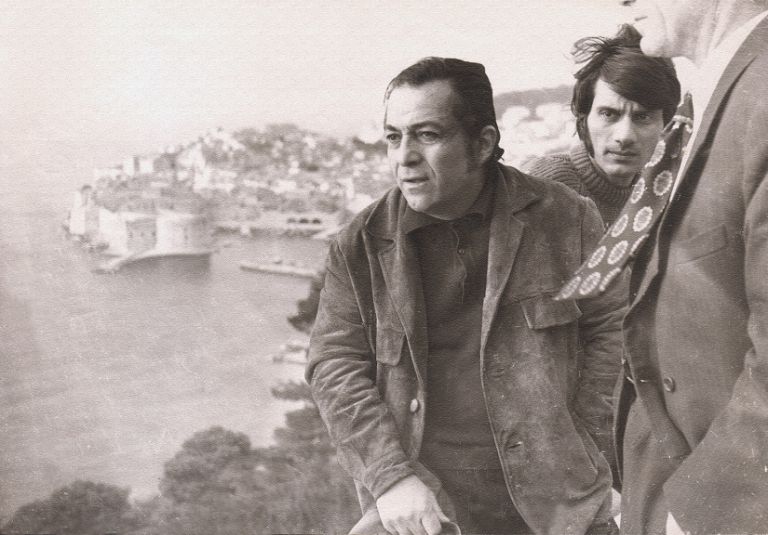

Rashid Behbudov

The more years that pass since he’s been gone, the more convinced I become that musicians and people like him are rare and timeless.

Trying to depict Rashid Medjidovich Behbudov, I sense a unique combination of extraordinary talent, good heart, excellent sense of humour - genuine human qualities.

I can talk about him forever, but there will never be enough words to do him justice.

When my grandfather Rovshan worked in the Song Theatre, an occasion brought him to the theatre storage room one day in 1974. While looking for something, he came across a vibraphone. After nights spent listening to The Voice of America, and in particular the Modern Jazz Quartet, he was very well aware of this instrument but had never tried it. Picking up the sticks, he played several chords.

I really liked that sound. It was very soft. Once in a while, I’d come to the storage room to practise. The more I learned it, the more possibilities to use it came to my mind. It wasn’t an assignment, just my personal interest.

That personal interest was what brought the vibraphone to the stage and ultimately it was used as an additional instrument on tours.

It added a complementary colour to the music, you know. The sound was warm, transparent even. In the Soviet Union back then, that [the vibraphone] added a novelty to the ordinary sounds that people were so used to.

In 1974, a musical film, 1001st Tour, was being produced about Rashid Behbudov, and due to it being a long term project, during which any concert activity was non-existent, the Ministry of Culture decided to reduce the number of people in the orchestra. Only those who were participating in the film’s production and musical recordings remained. Among them was my grandfather, who masterfully took advantage of his ability to play multiple instruments.

There were only four people left: drums, guitar, grand piano and me. But they also needed a contrabass player, so that’s where I started switching between instruments. While making the film, I was recorded playing pipe organ, bass guitar, vibraphone, which I then put all together on a phonogram. That’s why if you watch that movie, you always see me playing different instruments. Rashid Medjidovich [Behbudov] really liked me playing on a bass guitar, so ever since then I mostly played this at our concerts, occasionally switching to whatever the situation called for.

The more years that pass since he’s been gone, the more convinced I become that musicians and people like him in general are rare and timeless

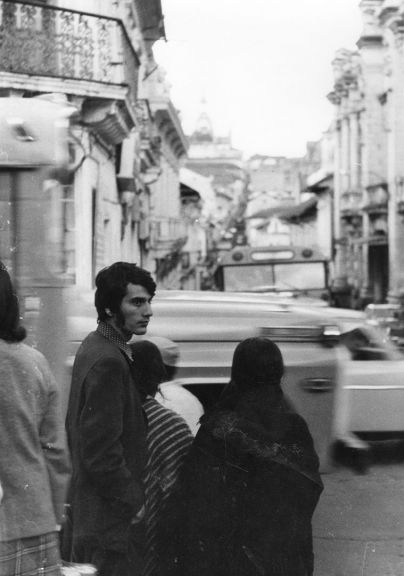

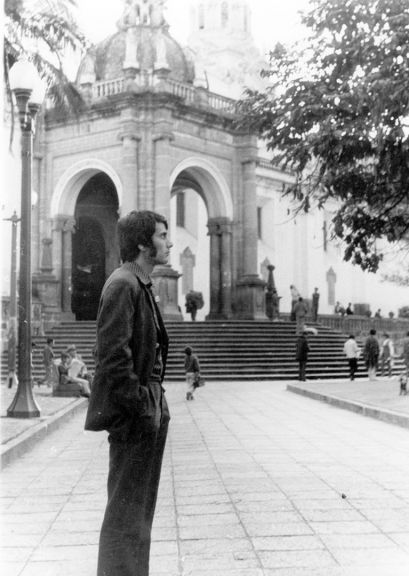

Latin America, 1973

Despite travels to so many remote locations, when I ask my grandfather for his stories, the Latin American tour beats all the rest.

It was the time of President Allende. As you may know, historically, there are always two ways to promote an understanding between nations: sports and the arts.

Choosing the arts, the Argentine government invited Rashid Behbudov and the band to give several concerts across Latin America. Keep in mind that travelling such distances for Soviet citizens was uncommon at that time, my grandfather said. Even travelling around the Soviet republics was sometimes troublesome because there always had to be permission, so travelling across the ocean added an extraordinary quality to this trip.

As a brief historical context, the year was 1973, and the people had just elected Peron, after about 30 years of rule of the “black generals.” While they were in power, not a single Soviet person ever went there. As we were told, this was because Soviet citizens were discriminated against: they were forced to give their fingerprints at the border. But with the election of Peron, this discrimination ended and an embassy even opened. Apart from the embassy staff, we were the first and only Soviet citizens to visit in 30 years, and it would be an understatement to say that people were surprised to see us when we got there.

While originally going to Argentina, we had to land in Chile to refuel. Only later did they realise that their visit was on the eve of the Chilean coup d’état, a 1973 army-led revolt that overthrew President Salvador Allende of Chile, the first democratically elected Marxist head of state.

As they were resting in the airport, Behbudov was contacted by someone from the Soviet embassy, who informed them of a request from President Allende’s administration for the band to stay in Chile longer and perform in several towns to support local people at this uneasy time. But since the band already had reservations in Argentina and all the tickets were sold out, this was a sensitive situation. The embassy representative assured them that everything had been resolved with the Ministry of Culture and it was left for Behbudov to make a decision.

He came back to us, because, as a rule, all decisions were made collectively, and we decided as long as there wasn’t any conflict of schedule, we would go ahead and play a couple of shows in Chile as well. However, we later found out that the person in the Ministry of Culture who had supposedly resolved the issue had been fired.

we were the first and only Soviet citizens to visit in 30 years, and it would be an understatement to say that people were surprised to see us when we got there

As soon as we were out of the airport, there was already a heavily secured bus with an armed escort waiting for us. Before we left for our tour, we were aware of the situation there. But we never could’ve imagined the amount of security we were going to get. As Soviet artists we were definitely a target. There were about 25 of us and the way that we were transported from town to town was simply astonishing.

The group of 25 was divided into twos among 12 separate buses. Each pair had to sit right at the back where there were no windows and two armed men accompanied in each vehicle.

We called it our “caravan.” And it had an appropriate escort for the occasion: two military cars in front and behind. At one point we stopped suddenly and in each bus, the armed men ordered us to lie down on the floor. We heard machine gun fire. Being a young, curious man, I peeked out the window: there were people running up and down the hill. When we started moving again, a while later, we saw a lone car, all burnt out. “This is what happens when you travel unaccompanied,” said one of the soldiers.

Upon their arrival at the hotel in Santiago, they were advised not to leave the premises with less than five people. It was less complicated to protect a group rather than individuals. All night long we could hear machine guns firing, my grandfather said. All the shop owners in town were prohibited from operating and anyone not abiding had their windows broken and goods smashed to pieces.

There were two towns in Chile considered the most dangerous, mainly because all the strikers were from these areas. Despite the swastika flags all around, it was especially important to perform there, for not everyone was necessarily supporting the opposition.

One stadium there I remember particularly well. It was in one of the towns where we weren’t allowed to leave our hotel. At a pre-arranged time a bus arrived to take us to the stadium. We couldn’t use the front entrance, we had to go through a number of underground tunnels to get to the stage.

As we were checking the sound, we were approached by the concert manager. He showed us the two rows where they believed younger, more troublesome people might sit. He said, “they wouldn’t have guns or anything, but beware of them throwing something. This shouldn’t happen, but in the unlikely event, please hide behind these stone walls.”

That, in a way, was kind of unnerving. The whole band was distressed about what was said and what might be coming.

Rashid Behbudov, wherever he gave a concert in the world, always started the show with the song Azerbaijan. It happened to be that the song had some Latin motives and the moment they started, the whole audience was up on their feet, cheering and dancing away. The two rows of youngsters were also dancing and never caused any disturbance at all.

It added a complementary colour to the music, you know. The sound was warm, transparent even to

Even in the most dangerous cities, where all the opposition was concentrated, the concerts went beautifully. Very soon people understood that this was pure art rather than Soviet propaganda.The masterful performance of Behbudov and his strong voice appealed to Chileans; the songs were about love and country, not politics at all.

Their last concert was scheduled to be back in the Chilean capital, Santiago, and the venue was in the city centre, close to the presidential palace, where the coup d’état happened later.

Our hotel was also not too far from the venue, so we set up all the equipment during the day and in the evening decided to walk towards the concert area. We knew President Allende was scheduled to attend, so we expected some serious security, given that they were extremely protective of us.

Imagine our surprise when we didn’t see a single security guard by the venue. We seriously thought the concert had been cancelled. We tried the door and it was unlocked. At the top of the stairs we saw the whole concert hall with people’s attention directed to the stage where at the presidium table was the president himself, along with his assistants. As we were informed, it was a regular meeting and once it was over President Allende wanted to greet us before the concert started.

Greeting us all with a handshake, the president thanked us for a successful tour, even in the most dangerous cities, wished us all the best and we proceeded to yet another concert, bringing our unplanned Chilean tour to a glorious end.

Lima, Peru

Physically, the concerts in Lima were the hardest: high up in the mountains it was always particularly hard to breathe.

At the beginning, whenever we walked, our blood pressure increased and every five to six steps we had to stop and catch our breath. After a while, we sort of got used to it. We were invited to perform there by the president, so, although hard, it was a great honour to be there. We worked three days, giving three concerts per day, which even in normal conditions is hard, but a far greater challenge at such a height. Especially for a vocalist.

Bolivia

They played in a great many cities. In one, they even experienced an earthquake. Usually the group divided into two per room at the hotel. My grandfather recalled:

Rashid muellim loved playing chess, we’d always come back after a gig and play a couple of rounds.

During this particular stay, Rovshan was sharing a room with another band member, guitarist Yuriy Sardarov, when suddenly the bed started to move.

That’s not funny, Rovshan said without opening his eyes.

I’m not doing anything, Yuriy replied with a rising panic in his voice.

Opening his eyes, my grandfather saw a chandelier rocking back and forth. The guitarist and the rest of the hotel guests rushed outside, while Rovshan stayed in the room. They were on the second floor and both windows were wide open, so he didn’t have any trouble hearing Behbudov call:

Rovshenchik

Beli (yes), Rashid Medjidovich.

Bala, why are you not coming down? It’s an earthquake, it’s safer here, outside, come down!

And here comes something I have been hearing from my grandfather all my life.

Rashid Medjidovich, what is written in the book of fate can’t be changed. If it’s meant for me to die in this earthquake, I will die either in this room or outside. What is written can’t be changed.

A smile spread across Behbudov’s face: Ok, everyone, did you hear him? Let’s go back into the hotel.

North America

Of the other tours in the region, I particularly like my grandfather’s story of travelling on the boat Odessa along the North American coast. There were two bands on the boat, Azerbaijani and American, which performed on different floors.

On this particular occasion, there was a storm and people abandoned the restaurant while the bands were still playing. In an empty room with only bottles rolling on the floor because of the heavy storm, the American band persisted with their programme. The Azerbaijani musicians came by and asked why they were still playing if no one was there and they explained it was part of the contract.

Don’t you have the same rules? Asked one of the musicians, to which my grandfather, knowing only a few words in English, said clearly: No people, no music. Everyone liked this catchy phrase and soon enough the American band was caught not playing by their manager. When he questioned them, they simply replied: No people, no music. The manager was so shocked by such bluntness that he came back at them with an equally blunt reply:

No music, no money!

* * *

Very soon people understood that this was pure art rather than Soviet propaganda

In the cold light of November my grandfather’s long hair appears whiter than usual and his eyes are fixed ahead as he recalls the memories from more than 40 years ago. Suddenly everything I knew about him has been redefined through the details of his adventurous life, which only now, aged 24, I can truly understand and appreciate.

I have been putting these tour stories and photographs together like a fascinating puzzle, challenging the stereotypes of serious, stony-faced Soviets that the world was getting at the time of my grandfather’s trips abroad. Sometimes, we don’t know the true value of a moment until it becomes a memory. He valued each moment of his unbelievable life, as I do now these precious memories.

About the author: Camilla Rzayeva is a staff writer at Visions