Hirkan National Park lies in the south of Azerbaijan. I first heard of it when I found out that there are leopards in Azerbaijan. A little bit of digging on the Internet threw up a few tantalising articles and I decided that one day I would like to visit Hirkan Park, home to Persian leopards. It was not so much seeing the leopards face to face, as the idea of being somewhere where leopards live that was enticing.

Hirkan National Park lies in the south of Azerbaijan. I first heard of it when I found out that there are leopards in Azerbaijan. A little bit of digging on the Internet threw up a few tantalising articles and I decided that one day I would like to visit Hirkan Park, home to Persian leopards. It was not so much seeing the leopards face to face, as the idea of being somewhere where leopards live that was enticing.One of Azerbaijan´s most famous trees, the Persian ironwood tree (Parrotia persica), can also be found in Hirkan Park. Although you can see it in many places in Azerbaijan, I was curious to see an entire forest of predominately ironwood trees, coming as they do from before the last Ice Age. What would it feel like to be in such a forest, I wondered. I discovered that Hirkan National Park is the place to go.

Some time later, I was discussing with Azerbaijan´s Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources my idea of visiting the National Parks. The ministry staff said they would arrange for me to meet Hagiagha Safarov, an Azerbaijani botanist who speaks English, and who has made the study of the flora of Hirkan National Park his life´s work.

I now had three excellent reasons for visiting Hirkan Park and I got more and more excited about the opportunity of experiencing its forest.

The attractive town of Lankaran is the best place to stay on your way to the park. It is a day´s drive south of Baku, some 260km. Long as this journey is, I do enjoy the variety of scenery. First, it´s the beaches and oil industry dominated desert scrub outside Baku, then the desert scrub inhabited by jeyran (gazelles) under the protection of Shirvan National Park. Have lunch at one of the many roadside kebab restaurants between here and the far side of Salyan. Stop to admire the salty lakes on the road to Bilasuvar, which attract so many birds, and then drive on down past Masalli to the green fertile fields at the foot of the Talysh Mountains. Vineyards line the roads, together with fields of colourful sunflowers as bright as in Provence. Fields of potatoes are a hive of activity with each horse and plough accompanied by a team of industrious potato pickers. Further on it gets wetter, and water buffalo laze in streams and ponds by the roadside. Tea and rice grow well in this climate. Take a detour up into the Talysh Mountains, to Lerik or to Yardimli; in May the green of the forest is so vibrant.

Lankaran provides a variety of places to stay, and for me the Qala Hotel is really quite comfortable, although I would recommend eating at an atmospheric local restaurant rather than in the hotel. Feast on lavangi, the local speciality (fish or chicken stuffed with chopped nuts and pomegranate).

Hirkan National Park occupies a significant proportion of present-day southern Azerbaijan (21,435 hectares), bordering Iran, and it is effectively part of a larger park in northern Iran. Here we have a fantastic example of two countries sharing the same conservation aims on adjacent land.

Hirkan National Park is mountainous and is covered (90-95 per cent) in a wonderful deciduous forest. My ironwood trees are found low down - yay, that saves me a climb. There are also chestnut oak trees here, together with Caucasian elms, date-plums (persimmon trees) and alders. A little higher, up to 600m, there are still chestnut oaks, together with hornbeam trees. Up to 1,700m, you will find oriental beech trees and Hirkanian box. Beyond this are Persian oaks and oriental hornbeam trees. Most of what lies above 1,700m is high mountain meadows.

So what really is so special about Hirkan National Park? Hagiagha explained to me about the flora here belonging to the time before the last Ice Age. Is this one of the most valuable wooded areas in the world? There are species of tree here that have been living continuously for millions of years. That is a longer time that I can imagine, and it is certainly a lot longer than the thousands of years that the old forests in Europe date back.

The diversity of plant species here compares with the best of the international World Heritage properties with 95 species of tree and at least 110 species of shrub. There are about 1,300 species of plants altogether of which 29 are endemic to Azerbaijan and a further 29 endemic to the Caucasus.

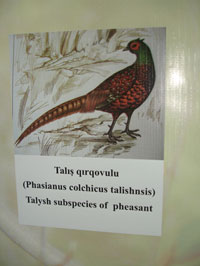

Enough plant facts and figures. Internet searches list exciting fauna too: 47 mammals including local endemics of Shelkovnikov´s vole and Hirkan woodmouse, brown bear, lynx, wolf, golden jackal, jungle cat, European otter and of course my leopard. And birds - 118 species including the white tailed eagle, vultures, osprey, peregrine falcon and endemic subspecies of Caspian tit and great spotted woodpecker. Don´t forget the 22 reptile species and the 10 amphibian species including the Caucasian version of the marvellously named parsley frog. No one has yet really studied the mosses and liverworts or the lichens or fungi.

First Hagiagha showed me the visitor centre for Hirkan National Park. You will find it on the right-hand side of the main road from Lankaran to Astara. There is a central area in the visitor centre where there are examples of the trees endemic to this region. Look hard, and then you will be able to recognise the trees when you come across them out in the forest proper. Pyrus hyrcana (Pear), Buxus hyrcana (Box), Ilex hyrcana (Holly), Ruscus hyrcana, for example - all tree species from Hirkan. In addition, you can see a local variety of fig tree, and an attractive honey locust tree. Do not miss the beautifully exotic silk tree Albizia julibrissin. Hagiagha proudly showed me the nature trail, designed for children. It´s still under construction, he explained, but to me it was already informative and exciting, and was on a par with interpretive centres in, for example, Forestry Commission or National Trust sites in the UK. Given our short timescale, there was no opportunity to reach the summit of the highest mountain in the park. This is the 1,816m-high site of Shendan Castle dating back 2,500 years. An interesting trek I am sure, but for this day a couple of trips into the lowland areas of the forest sufficed. First was a short walk through some forest coming out at the Khanbulan Lake. Hagiagha was a fantastic guide, pointing out the way that the ironwood trees grow into each other, so that two separate trees join together. He pointed out where trees had fallen, and the number of endangered plant species that had taken advantage of the light and favourable conditions to establish themselves. Look at this, look at that - and then the lake itself, beautiful in its undisturbed hollow, surrounded by the green forest. No major spring rains, unusual for this area, meant that the water level was lower than usual.

A tasty lunch of traditional Azerbaijani kebabs at Nijat Kafesi was followed by a visit to the most southern part of the National Park, where you can drive along the banks of the Astaracay River on the border with Iran. All the time Hagiagha was pointing out tree species, and showing me, for example, the variety of colours of the ironwood leaves, sometimes beautifully red. We stopped at the riverside Isti Su (hot water springs), and watched an example of the varying pace of Azerbaijani life, as a Mercedes was being washed in the river while a boy crossed over on a donkey. We discussed the need for conservation of the environment, and the need for villagers to continue to have their lives too.

Eventually I asked Hagiagha if he had seen the leopards. No, he replied, but I have seen their paw prints, and I can identify individual leopards by their prints. Close enough, I think.