Endless Corridor is a film produced and directed by Aleksandras Brokas. Narrated by Oscar-winning actor Jeremy Irons, it has invariably proved deeply moving to its audiences – reducing some to tears.

It covers the events and the aftermath of the massacre of 613 people that took place in February 1992 during the Nagorno-Karabakh War between Armenia and Azerbaijan. It follows two journalists, Lithuanian Ricardas (Richard) Lapaitis and Russian Victoria Ivleva, as they return to Azerbaijan to discover what had happened to survivors they had met at the time.

Justice for Khojaly, initiated by Leyla Aliyeva, raises awareness of that mass assault on the people of Khojaly and campaigns for restoration of the human rights of survivors to their land, homes and property. Over the last two years The European Azerbaijan Society has organised screenings of the film around Europe within the framework of the campaign to commemorate those who died. It has also been screened on the pan-European Eurochannel, CNN Turk and TV 24 (Turkey) channels, as well as on Israel’s Channel 1.

Visions of Azerbaijan met up with the director at a screening in Stockholm for an insight into the origins and thinking behind a film some five years in the making.

VoA: Why did you decide to make Endless Corridor?

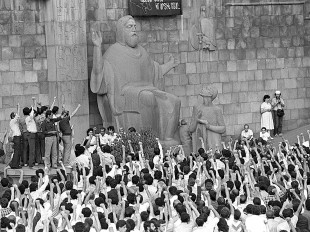

AB: There were a couple of reasons: one was that in 2009/10 I realised that stories like the Karabakh War and Khojaly still existed, that it wasn’t all finished. We didn’t have such big conflicts like that in Europe. And I thought that all the countries that came out of the Soviet collapse were alright and doing well. Then one of my friends told me that the Karabakh War was still going on, there were still people dying and this story was continuing.

Then I realised, when I was researching the war, that the story of Khojaly had never been told before. We had no idea about it, and we had no idea about the Karabakh War, as we were hearing only one side of the story, from Armenia. And it was a small shock to hear another side.

That’s how I found the film.

So when did you come to Azerbaijan?

For me, as a Lithuanian filmmaker, it was very important to hear their stories. You know we and the Caucasus have a similar, sympathetic spirit. We had many connections in Soviet times, we heard a lot about each other. We are like brother countries. That’s why it wasn’t very difficult to do the research.

The first project we did in Azerbaijan was about a cultural exchange between the two capitals: Vilnius as the European cultural capital and Baku as the cultural capital of Islamic countries, that was in 2009.

Then we went more into the story of Nagorno-Karabakh, and we found those refugees and their stories, which were so deep and touched us so much. We started to look at what we had on our side, what our people remembered from those days and what they could tell us. That’s how we found Richard Lapaitis and Arturas Zuokas, a former mayor of the city [Vilnius – ed]. They let us read their diaries from those times and we found some interesting stories.

We thought it was very important to tell the world. This was before Ukraine, but after Georgia, and we wanted to show how stupid war is.

What problems, political or practical, did you have in making the film?

Right in the early stages we understood that this was a very sensitive topic, both politically and in that some people wanted to forget everything that happened to them, and we knew that it was not going to be easy.

But we went on with research, we looked for international journalists, we wrote synopses and a treatment. It was a long process… We engaged television companies, whose reporters went to Armenia and Azerbaijan to shoot film. The idea from the beginning was to involve crews who could do something for their own television stations and we could edit the material to make a cinema movie – and to share the archival materials that the TV companies had.

Was it difficult to coordinate all those crews?

We understood that crews that went to Armenia couldn’t go to Azerbaijan, especially those that went to Nagorno-Karabakh. Because it was impossible to go there [across the militarised front line – Ed.] from Azerbaijan, they had to cross the border from the Armenian side, and then they would have problems at other Azerbaijani borders. So we had to choose different crews. It was also important to have as much independent material as possible. You know when you become familiar with people you start to sympathise and become involved with them. So it was important to have separate crews to get very independent material.

Unfortunately Armenia deported two crews. It may be because we sent a list of the people we wanted to interview, but I’m not sure. A third crew got in because the purpose was kept secret.

Why do you think the Armenian military men agreed to be interviewed?

It’s difficult to say… but in the movie they don’t feel any guilt or confusion – the opposite; they tell their story and it was important to give all sides the chance to say their own opinions. And when we see what happened in the end, we were surprised. They were so proud of organising an attack after which more than 500 people were killed; they say in the interview that nobody can prove it… and nobody had researched it.

What do you think about the Armenian general’s anger with politicians?

It’s a normal human reaction. He’s the general, he’s the one who organized it, they invited architects, and he’s proud of everything that he did. But when the question is why the civilians were killed, then he says that was another situation, that there was some kind of command that they had to do it, so of course he doesn’t want to take responsibility for that.

What do you feel about the public response to screenings of the film?

The movie was made for regular people. It doesn’t matter if you’re a politician or ambassador or a journalist or artist, or whatever; this movie is for everybody. Because when you see somebody’s story, life story, you always get involved…. So I am happy that different kinds of people can see it. Screenings at film festivals, when people are discussing it deeply from a professional point of view, are totally different from when people are watching and are involved in a story they had no idea about, but are touched by it. It’s always interesting to see how people react after it, especially when there are questions at a Q & A session; then you can feel what people finally understand from it.

So what is the ultimate purpose of the film?

People should realise that starting wars and killing people is the most stupid thing that can be done on earth. And if we have minds and brains in our heads, we have to find a way to avoid these conflicts. This is the only way we will survive on this planet. This is not only for our generation, I’m talking of the generations that will come. For me the question is, what will we leave after us, for our children and grandchildren? And when you see generations living in such fear now it’s horrible, really horrible.

Has there been a moment in these screenings that stands out for you?

In Vilnius, when we held the first premiere and we had 600 people in the hall, and all the crews… and Victoria, Richard…. on stage. There was a really special feeling. Normally, all of those people couldn’t meet together. And the feeling was that this movie had brought everybody together and put them in the same time and same place. It was very strong, and afterwards people came out of the audience; you could see the tears in their eyes, and everyone was hugging, it was so deep. I don’t remember anyone saying they didn’t understand what it was about. The reaction was always very deep and sensitive.

Your next project will focus on women. Did your work on Endless Corridor influence your choice of subject?

Of course! The mystery between the two women, Victoria and Mehriban, made us think about the importance of the role of women in our lives. We started to search for the right character and a woman who could represent this personality… a woman to represent a woman’s way of life, in all dimensions.

We found a woman writer and astronomer who spent more than thirty years meeting people, writing books and explaining how to live without conflict and fighting. She’s an astronomer, a member of the Russian Writers’ Union and has written more than 400 books. She says that if humanity could remove information about conflicts, peace in the world is possible.

People have to learn to live with a higher form of energy. Love is the only fair and very powerful energy on earth. If people learn to live with love then it will be possible to solve these conflicts. That’s the main aim of the new project.

Has making Endless Corridor changed your life in a radical way?

This movie changed my life a lot. When you watch 200 hours of archive material, ninety per cent of which is dead bodies, yes, it changes your life. Then you understand how short life can be for people. That means that we have so little time to change it and to start new conflicts is even more senseless, knowing that the life we live is so short.

And how do you feel about the Khojaly survivors?

They are very strong people, very strong in spirit. The situations in which they lived, not everyone could stay with that. Only their strong spirit lets them enjoy life. Valeh is a musician, he still plays guitar. Mehriban told us how she makes bread for the village. They try to raise themselves and they have some kind of light inside them. It makes us think. Sometimes we are sad, but compared with them…. They are still positive, and we should be the same.