Early summer is the best time to visit this fascinating Azerbaijani exclave, which is also easily reachable from Baku, as Tom Marsden found out…

Gazing through the tiny window at the arid landscape below I quickly came to understand that there was something quite different about Nakhchivan. The reddish, martian terrain was very unlike the emerald green mountains of northern Azerbaijan and the view of the neatly planned capital on the approach in to land revealed a very different world to where I had just come from - built-up and bustling Baku.

Leaving the airport this sense of otherness only grew as several times I was questioned, politely, over the purpose of my visit, after all I was probably the only non-Azerbaijani. First I was approached by an overly smiley man in a dark leather jacket, and then by a taxi driver, Rovshan, who quickly took me under his wing or saw a business opportunity. His first job was to keep me from panicking when “passport control” happened very unexpectedly in the car park and involved passing my documents through the taxi window, together with a business card and an old copy of Visions.

What’s all this about? I asked Rovshan. Well, we’ve got the elections coming up, he said, thinking little of it. Elections or not, in truth I expected the Nakhchivanis to be security conscious. It’s understandable, given that this fascinating Azerbaijani exclave is wedged between Turkey, Iran and hostile Armenia, which blockaded Nakhchivan for a year during the Nagorno-Karabakh War. The blockade was broken with the return of national hero Heydar Aliyev (a native of Nakhchivan) and the construction of a life-saving bridge to neighbouring Turkey.

The Armenians were thinking “Karabakh is the bride, Nakhchivan will be the gift” - a Nakhchivani would later tell me, alluding to local wedding practices.

Nakhchivan City

Rovshan drove me the short distance into Nakhchivan City, the capital of this autonomous region of Azerbaijan and the best place to base oneself given its decent hotels and central location. The city itself is clean, colourful and pleasantly, perhaps eerily, calm. I wondered why there was so little traffic, why the cars were moving so slowly, why everything was so spotless and tidy?

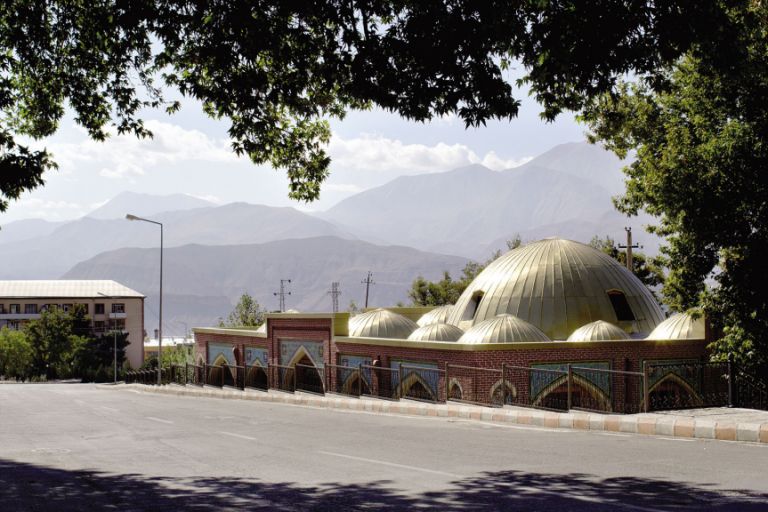

We have a strict regime, Rovshan remarked. Over the next few days I was struck by the wide boulevards carving between once-grim Soviet-era apartment blocks that now glimmered with creatively golden, blue and maroon facades. Taxis were a Manhattan-yellow, ran to a meter and drivers wore special tracksuit-like uniforms. In between all this were well-preserved reminders of the region’s ancient past – Momine Khatun’s (leaning) mausoleum, the gold-domed Blue Mosque and the sunken Old Hammam. I liked Nakhchivan.

Following my questioning at the airport, alarm bells rang again when a well-groomed young man in a smart black suit approached me in front of the Heydar Aliyev museum, with suspiciously good English and a generous offer:

I’m from the Ministry of Culture, he said, Can I show you around?

Relieved that I wasn’t being told off for photographing the wrong thing, I agreed and moments later we called in at the Old Hammam, now a teahouse, where young men filled the dark interior with chatter, chay and the aroma of shisha. After, we walked past the local TV station – Nakhchivan has its own television channel – and an old mausoleum set between one-storey houses surrounded by equally high walls. Having planned to wander until well into the evening I was a little disappointed to find that before long I had been escorted all the way back to my hotel, the Grand (35-40AZN).

The other (more upmarket) hotel to pay attention to is the centrally located Tabriz, which is worth visiting for its top-floor bar alone. Up there are breathtaking views over the city and south towards the River Araz, beyond which tower the rugged mountains of northern Iran.

This proximity to Iran was to become a feature of my short stay in Nakhchivan and began later that first afternoon when that same driver Rovshan swerved off the road leading north-west from Nakhchivan City and, once upon a time, all the way to Yerevan (140km). Instead we headed to Duz Dag or “Salt Mountain,” a former Soviet salt mine which is now a hotel and salt treatment centre, built around a long tunnel carved into the mountain, sparkling with salt crystals and bathing in silence and salty air. After darting in and out again 30 minutes later I found Rovshan chatting to the only other visitors, who had driven from Iran.

It was then that I came to a peculiar realisation: only in Azerbaijan can a day begin with a chocolate-sprinkled cappuccino in Baku and come to an end enjoying aromatic herbal tea and Iranian sweets with tourists from Tehran, at a Soviet salt mine in land-locked Nakhchivan.

Ordubad

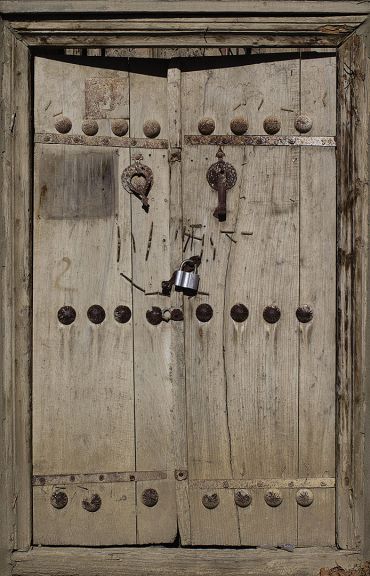

The following day the Iranian theme continued as I followed the Araz along Nakhchivan’s southern border, past the jagged cleft of Ilan Dag and through the stunning red-rock landscapes all the way to the ancient town of Ordubad. This town is located on the very southeastern-most tip of Nakhchivan, at the junction of Armenia and Iran. It has narrow, mazy streets, old doors with double knockers (warning of the presence of man or woman in times gone by) and perhaps the world’s most expensive lemons. A tea, jam and lemon set cost 10 AZN at the teahouse on the little bridge behind the History Museum.

You won’t find many tourists that make it to this hard-to-reach corner of Azerbaijan and in the past wielding a camera may well have attracted unwanted questioning from the police. On my visit this wasn’t the case, the only discomfort being prolonged stares from the few pensioners hiding in the shade of a huge chinar tree. Otherwise the town seemed largely empty and basked in a surprising autumn heat. I was soon to learn the reason for this desertion. Reaching the northern tip of the village I heard loud chanting reverberating through the mountains, or perhaps from behind the mountains – was it a football match in Armenia?

Walking a few hundred metres east I caught sight of crowds of black-clad Ordubadis flooding towards the cemetery at this edge of town.

Come up and have a look, one of them said, today is the day when we come here to pay our respects to our dead relatives.

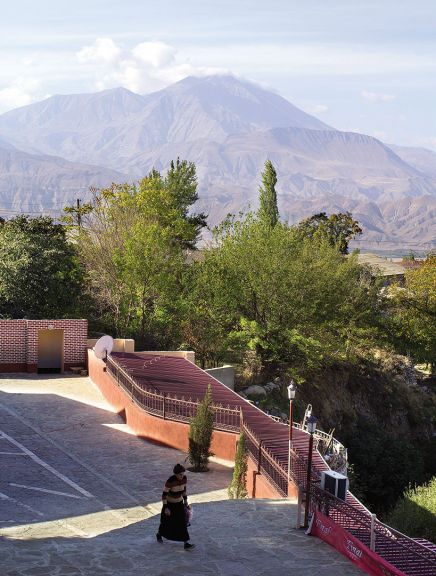

The chants were echoing unnervingly from further up the stony path, at the top of which was a plateau at the foot of the mountains. There the sun was beating down on 30 to 40 young men, dressed in black, swaying back and forth to a steady rhythm, beating their chests and repeating lines from the Qur’an. Men were perched in groups on the rocky hillside whilst women in colourful headscarves crowded at the edge of a stream opposite. I clambered up and joined a group crouching on the hillside and needless to say I stood out like a sore thumb.

Osman was a wiry man who had lived in Moscow for 30 years. The population, he said, had once been about 40,000 but had dropped to about 5,000 in recent years; many had left, some for work, some for something else. Soon enough, Osman was demonstrating the sort of hospitality that I’ve come to expect whilst travelling in Azerbaijan.

Tom, if I had the means, I’d say let’s get some food, get in the car and go and spend the day in the mountains.

Unfortunately, neither he, his friends or I had the time, so I scooted off to find my driver, Abulfaz, and off we drove back past the extraordinary landscapes of southeastern Nakhchivan.

Heading North

On my final day I decided to head north to Lake Batabat, about an hour’s drive from Nakhchivan City. Like the east, this northern part of Nakhchivan was cloaked in all the colours of autumn and we were cruising along smooth roads, which according to today’s driver, Fuad, could only have been dreamt of as recently as five years ago.

Fuad was an animated chatterbox eager to outline as much local history and culture as the hour-long drive and the surface of the steering wheel would allow. Aluminium, glass, tinned food, textiles, carpets, champagne and cigarette factories used to operate here and a railway functioned transporting those goods between Moscow, Baku, Nakhchivan and Yerevan. That railway came to a halt after the fall of the USSR and since the Nagorno-Karabakh War Nakhchivan hasn’t been connected by rail at all.

The proximity to Karabakh added a particular sensitivity to the topic. It was all very simple according to Fuad, you invite the Armenians into your house and after a while they start claiming things.

“Dolma,” you can’t take this word and say it’s yours. Tom, tell me something English, anything.

Erm, ok, “sandwich.”

“Sangwich” … right Tom, tell me, can I enter a competition and say, “and this is the Armenian national sangwich”? It’s ridiculous, come on…

Lake Batabat

As we approached Batabat brooding clouds pierced by rays of sunshine added extra drama to the exquisite scene. Rolling mountains descending towards the murky water and rolling grassland filling the horizon for as far as the eye could see. According to Fuad, Azerbaijani troops patrolled the tops of the mountains to the north of the lake and beyond this is the border with Armenia.

Karabakh is three times more beautiful than this. That’s why the Armenians wanted it, he said solemnly as we drove around the lake.

Fuad continued with a few more interesting facts. The name “Batabat” came from the squelching sound caused by stomping one’s feet around the lake, which was flooded until about 20-25 years ago. The temperature up here was noticeably cooler: in summer it could be 20°C at Batabat whilst it’s 40°C in Nakhchivan City. Yet strangely the water is icy cold in summer and much warmer in winter. Early summer is the best time to come, when the flowers add greater colour around the lake. But autumn certainly didn’t disappoint, the trees on the hillsides had turned the landscape a stunning caramel brown.

In summer the lake bustles with picnicking Nakhchivanis but despite the favourable weather during my visit there was almost no one. Almost. One family was picnicking a few hundred metres from the lake on a colourful rug, with a wood-fired samovar steaming away. They had driven a minibus from a village near the airport. They had also brought two goats, one of which now sizzled on the portable mangal, and of course it was no surprise when I was obliged to try the ultimate fresh shahlyk. What was surprising was the manner in which I was supposed to eat it, as my plate was ceremoniously placed on the stone used to sacrifice the animal. The men grinned and awaited my first bite and I began toiling away at the oily, chewy meat and swivelled to see the goat’s head a metre or so from my foot. Fortunately Fuad was on hand to polish off what I wasn’t able to eat.

Soon after we said our goodbyes and careered off through the epic countryside all the way back to Nakhchivan City for a farewell trip to the Hotel Tabriz. There I enjoyed a final tea served by a waiter from Turkmenistan and gawped across the Araz at the sun lowering over northern Iran. It was one last multi-cultural twist in the Nakhchivani tale, before the lights went out over the Araz and soon after the curtain came down on my time in Nakhchivan.

Getting there:The simplest way is to fly from Baku. For this you will need to buy a ticket from the AZAL office behind the Rashid Behbudov Theatre on Nizami Street (126A) in central Baku. Tickets cost 50AZN for Azerbaijani citizens and 70AZN for foreigners. For the more adventurous, a bus travels to Nakhchivan from Baku via Iran, which will require a visa to transit through Iran. If you are keen to try overland routes and combine trips to Georgia and Turkey then see travel writer Mark Elliott’s Nakhchivan Revisited, published in the January-February 2015 issue of Visions (www.visions.az/travel_tourism,620/). |