It was February 1931 when she made history. A woman sat behind the control wheel of a U1 (some say a U2) plane, with her long braids tucked under the safety belt. The plane took off and within minutes she was at the controls of her very first flight, with a proficient instructor. A few months later, on one of those hot summer days she made her first solo flight, happy and confident: she was to fly again and again. Leyla Mammadbeyova had become the first woman pilot, not just in Azerbaijan, but in all of the East and Southern Europe. She it was who surmounted all the stereotypes of the day to be a source of inspiration for generations to come.

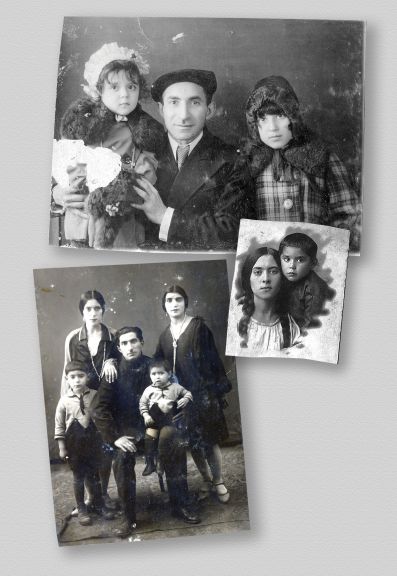

Khanlar and his mother in a million

As I looked through the newspapers and copies of interviews scattered across my desk I was full of questions: Why? Why did she decide to do that? What did she feel? I was looking for stories of her childhood when I suddenly got the chance to contact the youngest of her children – Khanlar Mammadbeyov. After several frustrating postponements, we finally met on another warm day – this time in March. I was so excited to meet a son of that great woman, who deserved her name of Ruler of the Sky. Happily, he turned out to be communicative and easygoing, perfect for our two-hour-long interview, which flew by as Khanlar was clearly very happy to talk about his mother.

Tough childhood

You may think she was a dreamy girl, but we were surprised to hear the contrary. She never wished to be a pilot. As Khanlar explains, in those times planes didn’t fly like they do today, people were scared of them. His mother, Leyla, was born in 1909 in Nardaran, a traditional seaside village on the beautiful Absheron peninsula. She was an only child. Her father had three brothers and a sister with the same name – Leyla, who died young; she was only 18. After the four brothers had lost their only sister they made a promise that the first girl born to any of them would have her name.

The little girl lost her mother at a very early age and grew up in a very determined family. Her father, Ali Asger, Khanlar’s grandfather, was an activist and often took her to Baku and Astrakhan on revolutionary business. As they moved often, they lived in rented houses. Ali Asger was a member of the Hummet Party (the Muslim Social Democratic Party) and he was against the ‘Whites’ during the Russian Revolution of 1917. The same applied to one of her uncles, who was jailed and later died in Iran. Khanlar’s mother had recalled those days of revolution: struggle, sounds of gunfire, soldiers running, many injured and dead bodies all around. She once witnessed the burial of 50 people. Amid this awful scene a little girl with a white headscarf and red cross ran and ran carrying notes in her little hands. She was a messenger, trying to help her father and others in any way she could.

She was aware of how dangerous a move this was: everyone around her was very old fashioned, women couldn’t just do whatever they wanted

According to Khanlar, Mirjafar Baghirov (later the leader of Soviet Azerbaijan) visited them from time to time. As a supporter of the ‘Reds’ he hid in their house, not realising that he scared the little girl. Later she remembered him as a big man with glasses. Life under such pressure made her stronger.

People in her circle were unhappy with such bad living conditions, they wished for freedom and a better life, explains Khanlar.

Finally, Baku!

Relying on his mother’s stories, Khanlar tries to remember when she finally settled in Baku. She was 10 or maybe 11 years old – he decides.

As a child she loved to travel on a phaeton all around old Baku. When the phaeton drivers asked her for the money, she always had the same answer; “Ali Asger muellim will pay for me!” He was a respected man, everyone knew him.

They lived near Teze Pir mosque (a popular mosque in the centre of Baku). One of the new houses they lived in was owned by her future husband and his father. My parents met each other there and were soon married.

They were young and in love. As Khanlar says, he doesn’t know their exact ages at the time but there was about nine years between them. It wasn’t an early marriage for the time, and it was legal. She already had her first child by the time she was 16. When the Soviet rule was established in Azerbaijan all their property was taken away and Bahram became a worker. Later (in 1927) he joined the ranks of the communists and began a new career as an ordinary printer. He and his fellow printers joined togethet to build the first cooperative house in Azerbaijan. Bahram finally became a bank manager.

Finding her wings

Along with other women in Baku, Leyla attended Abilov’s Club, a place for women to receive an education. It was a sign from the heavens that suddenly, in 1929, the Aviation School was opened right next to her home. It wasn’t a big building by today’s standards, it was just a space designed to teach future pilots. She heard about it first from her friend Zibeyda, who was very excited - girls were welcome to apply. So the two women decided to take a chance on destiny. The ‘exam’ was simply a medical check-up. However, due to heart problems Zibeyda wasn’t accepted. But Leyla was; she was the only woman among the 22 accepted.

By management instruction her school visits were top secret. Only Bahram knew, and he didn’t stand in her way. He was also influenced by the communists, who were very interested in her studying there.

It was a chance. She just had to go through with it - and she did, despite everything, says Khanlar.

She was aware of how dangerous a move this was: everyone around her was very old fashioned, women couldn’t just do whatever they wanted. Later in Khachmaz she was the victim of an assassination attempt. So it wasn’t simple; it was even rumoured that she had left for Iran. But she wanted freedom and was an example for others.

She was only 22 when she got behind the wheel of a plane and after graduating she was sent to Moscow for further training. But there was a problem… the children. Mirjafar Baghirov it was who urged her to go, promising to arrange a nanny for the two little children.

She was very disciplined. They told her to go and she went.

Moscow, haircut and first jump

The young woman was already in the Soviet capital in 1933. This period may have been the most significant of her life. She was urged to cut her long hair as it posed a danger in an open cockpit. While she was studying there, her name was already appearing in the press. One magazine, Ogonyok (Flame), printed a front-page headline: Turkic Woman – the First Female Pilot in the East. At the same time, on the other side of the world, a young English woman, probably a pilot or journalist (still unknown) was totally confused. She was so surprised to see the photo of an oriental woman pilot that she decided to fly to Moscow and meet her. Khanlar still holds their photograph together (1933), trying to find out who that mystery woman from London was.

Her husband let her do what she wanted - says Khanlar, If he hadn’t supported her, she wouldn’t have ever flown. But there are always exceptions.

17 March 1933 is another notable date in history. A few days earlier she had called Bahram and talked about life in Moscow. She mentioned that parachutes had just been brought to Moscow and… her decision to jump. That was a real shock; her calm, understanding husband had an abrupt change of tone. How? How could a woman, a mother and his wife take such a risk? If the parachute didn’t open, who would take care of the family?

Despite the fact that a parachute jump then was a real performance she was determined to do it. Imagine how you climb out of the plane, stand on a wing and jump backwards, all alone, with no one pushing you.

It started well. Then something was wrong. The parachute failed to open. She tried to pull it out but the ropes tangled in her legs. She was face to face with death, when the second, emergency parachute finally billowed into the air and she lived to be one of the first women parachute jumpers in the Soviet Union. One year later she jumped again and took first place in a competition between the Caucasus Republics.

But the worst was to come on her return to her homeland…

Pilot, doctor and WWII

After putting so much effort into her chosen path to fly, Leyla was hardly going to accept that she would never fly again. But arriving back home she was appointed director of a library and grounded. Imagine her anger after so many trials and risks. Fortunately, friends from the administration came to her aid, and she took to the skies again.

A very amiable woman, Leyla often visited women in different regions of Azerbaijan and took them up in her plane. They loved her idea of the free woman, swirled around her and learned new, modern things. Sometimes she took children up into the clouds, thought to be a cure for whooping cough.

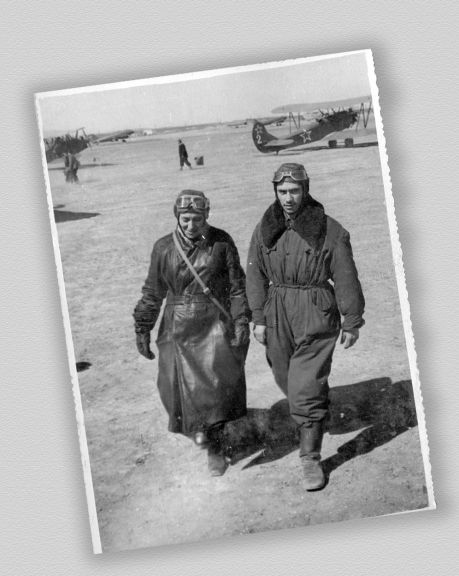

From 1933 -1941 she worked as an instructor at Baku Air Club and later she headed the Pilots’ Club. But when WWII began, as a mother of four children she wasn’t accepted to fight at the front. Instead she was engaged in a long struggle to open the Glider-parachute Club, where the instructors consisted mainly of three people: Mikayil Svarenko and his wife Tatyana, and Leyla. She tested all the injured pilots before their next flight and by the end of the war she had trained about 4,000 paratroopers and hundreds of pilots. Two of these, Adil Guliyev and Nikolay Sheveryayev, became Heroes of the Soviet Union.

She was very hardworking. The electric train took them only as far as Sabunchi. From Sabunchi to Zabrat (nearly 4 km, 2 miles) then they had to go on foot. She woke up every day at 3am to get to work at 9… By the way the Soviet Union’s first electric train was launched in Baku.

She could fly four types of aircraft. Mum told us how some planes flew on castor oil, can you imagine that?... There was a story that once when her fuel was running out, she landed in Garadakh and was met by some of her students. Imagine… they fueled her plane with petrol - a strictly forbidden practice! She could have been arrested. So she had to circle in the sky for some time before the petrol ran out and she could land at the aerodrome.

It started well. Then something was wrong. The parachute failed to open. She tried to pull it out but the ropes tangled in her legs

After the war Leyla worked in different positions at the Baku Air Club. 1949 was her last year as a pilot. At the age of 40, after 20 years of life in the fast lane, she said goodbye to the skies. That was when I was born - and she had health problems, explains Khanlar.

She went on to work as a director of a soft drink factory and a deputy head at DOSAAF [a paramilitary sports organisation – Ed.].

Motherhood Medal

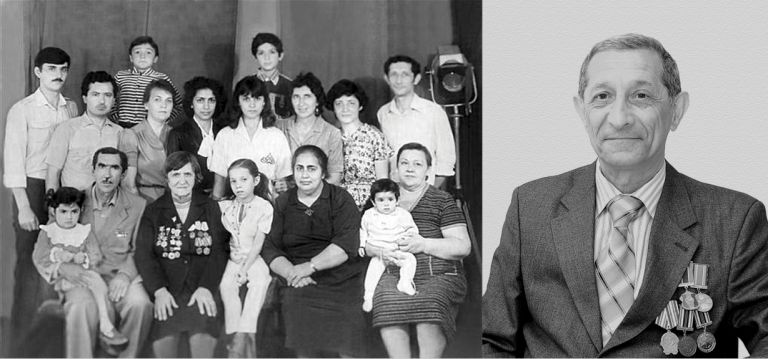

She was blessed, not only for being the best pilot, but also for being the best mother of six children. She lived to see her grandchildren and great-grandchildren. She was even given a medal for motherhood, the most prized of all her awards. In 1943 she saw her eldest son, Firudbek enter military service. Khanlar was the youngest of her family:

There were 23 years between Firudbek and I. He was the only one of us without a higher education - because he served for seven years.

It’s hard to believe that with everything else she did in her life, Leyla also brought up such a large family. The number of children could even have been more than six.

I am the second Khanlar in the family. The first one died very young. Traditionally if a child dies, the next one to be born is given the same name, to cheat death.

Khanlar’s two sisters and two other brothers are soldier Rustam, biologist Elmira, PhD in agriculture Zemfira and geologist Vagif.

And me, Khanlar, with a broad range of interests - economist, philosopher and a major in the military.

I wondered why no one had followed in her slipstream, perhaps some of her grandchildren wanted to take after their great-grandmother?

Can you imagine? I don’t wish to even drive a car. It’s the same with my daughter, Khanlar tells me.

She woke up every day at 3am to get to work at 9…

His father, Bahram, died early, aged 52. People didn’t live long then, affirms Khanlar. But I still wonder how, in those days before modern conveniences, a woman could do that kind of work and take care of such a family. But Leyla was very thrifty; Khanlar recalls times when his mother and all the adults would get together to cook Novruz sweets (for the main spring holiday in Azerbaijan): shekerbura, pakhlava, gogal, etc.

In the early 1930s the Azerbaijani director Mikayil Mikayilov made the film Ismet, dedicated to the first woman pilot in Azerbaijan. Leyla performed lots of complicated tricks in the movie. We can’t be sure, but she may have been the world’s first woman stunt pilot. Khanlar is looking into this. In some of the photos she looks very modern and fashionable, her son agrees that she was very stylish. Leyla could also speak French and played the tar. It seems there was no end to her energy or accomplishments.

Finally…

There is a story that on one International Aviation Day Leyla received a greetings card. It was from Khanlar, serving then in Kishinev. She was surprised to see that the congratulations were addressed not to her, but to her husband. When they finally met, she asked why he had congratulated his father and not her. Khanlar was puzzled. He went straight to the post office to find out what had happened. It turned out that the post office staff hadn’t believed that the pilot might be a woman, so they had corrected the ‘mistake’ by readdressing the letter.

We can’t be sure, but she may have been the world’s first woman stunt pilot

It was such a pleasure to hear Khanlar’s lively stories from his mother’s life and to be amazed at this great woman’s rich and full life. For me, her life was a breakthrough for the international women’s movement in the early part of the last century. Who knows, if history repeats itself perhaps someday one of her descendants will inherit their great-grandmother’s talent.

About the author: Narmin Mahmudova is a young writer with an interest in women’s issues.