Caucasian Days (1945) is the memoir of Azerbaijani émigré writer Umm-el-Banine Asadullayeva, better known simply as Banine, whose life spanned almost the entire 20th century. In it she describes her privileged life growing up in early 20th-century Baku and bears witness to the turbulent events of the end of World War I, the rise and fall of the ADR and the establishment of the Bolshevik regime in Azerbaijan, which led Banine to emigrate to Paris in 1924. Her story is quite extraordinary, as Tom Marsden explains...

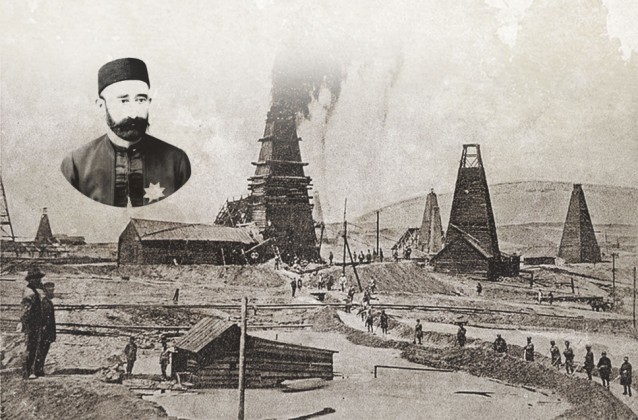

Banine in 1906 (left) Mirza Asadullayev with his four daughters (centre) Banine was named after her mother, Umm-el- Banine (pictured), who died in childbirth in 1905 (right)

Banine in 1906 (left) Mirza Asadullayev with his four daughters (centre) Banine was named after her mother, Umm-el- Banine (pictured), who died in childbirth in 1905 (right)

Early life

Banine was born the youngest of four daughters at the height of the first oil-boom into one of Baku’s wealthiest families. Both of her grandfathers were oil magnates, Shamsi Asadullayev on her father’s side and Mirza Agha Musa Naghiyev on her mother’s side, and her father Mirza Asadullayev went on to run the family business and serve as the minister of trade and industry under the short-lived Azerbaijani Democratic Republic (1918-20).

But despite the family’s riches tragedy struck early: Banine’s mother died in childbirth while escaping the Armenian-Azerbaijani pogroms of 1905. Instead she and her sisters were raised by a Baltic nanny of German origin named Fraulein Anna, and were taught German, French and English from an early age. Summers were spent in the cooler climes of Mardakan on the Absheron peninsular, where Banine’s imagination would run wild in the extravagant garden:

My friends in the garden were everywhere. They included a pear tree, and bindweed, and rose bushes, and the pool and even the stairs. I chose these friends myself and was very happy with them. As opposed to people, they remembered goodness and knew how to be noble. And I related to them with fondness and care. (Caucasian Days)

Her father eventually married again, a glamorous Ossetian woman named Tamara Datieva who was cultured, fashion-conscious and western-oriented. However, the family was soon caught up in the whirlwind events that swept through the Caucasus following the October Revolution and the end of the First World War. The fall of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic in particular signaled a dramatic change:

The four sisters’ peaceful life came to an end in April 1920, when the Bolsheviks captured Baku. The new authorities jailed Mirza Asadullayev, a former minister and prominent businessman. In order to save him, his 15-year-old daughter, Umm El-Banu, had to marry Balabek Gojayev, wrote Mr Ramiz Abutalibov, a Paris-based Azerbaijani diplomat, for Baku Magazine in 2008.

Gojayev facilitated the release of Banine’s father and arranged a passport for him to emigrate to Paris in 1920. But the early 1920s remained a turbulent period for Banine; having witnessed her father’s deteriorating health in prison she was then obliged to marry a man she despised. She left Baku only in 1924, travelling first to Istanbul, where, after months of waiting for a passport, she boarded the Orient Express, abandoned her heart-broken husband and rode off to join the rest of her family in Paris. She was still only 18.

Parisian Days

They were renting an apartment in the prestigious 16th arrondissement and surviving by selling the family jewels. Like all emigrants, they were hoping to return home in a year or two, wrote Mr Abutalibov, who befriended Banine in her later years.

But the Asadullayevs’ hopes faded as quickly as the family jewels and Banine, aided by her excellent French and desire to assimilate, began to establish her independence:

I have lived in Paris for twenty years. I have had the most diverse jobs here: model, sales woman, secretary, music teacher and, finally, writer, she told a French newspaper in 1947.

Her first book Nami appeared during the German occupation of Paris in 1942 and was about the collapse of social structure in Azerbaijan. Then came Caucasian Days (1945), generating her first literary success. The follow-up, Parisian Days (1947), focused on the life of émigrés and bohemian society but was met with less acclaim. Later works included Meetings with Junger (1951), I Chose Opium (1959), After (1961), Foreign France (1968), Call of Last Resort (1971), Portrait of Ernst Junger (1971), Ivan Bunin’s Last Duel (1979), The Many Faces of Ernst Junger (1989) and What Mary Told Me (1991).

Of those, I Chose Opium, a testimony of the author’s conversion to Christianity and her quest for spiritual nourishment, was Banine’s second major literary success. Her most successful work was largely autobiographical and contained themes of East and West and émigré life, often infused with sharp observation and a wicked sense of humour, which spared nobody, herself included. She also translated the likes of Dostoyevskiy, Tatyana Tolstaya and Ernst Junger into French, and was gradually introduced into Parisian literary circles through neighbours and friends, in particular the Russian writer and satirist Teffi.

In her long life, especially in the successful periods, she met a lot of famous people, especially writers but also politicians as her friends were always well connected and implicated in both cultural and political life in France, wrote Rolf Sturmer, heir to Banine’s literary estate, in a letter to an Azerbaijani journalist, adding:

Judging from her personal documents, I believe, that her friendship with the famous Greek writer, Nikos Kazantzakis, and with his wife Elena, was the closest, warmest one.

The two other writers to play a significant role in Banine’s life were Ernst Junger, the German war hero, naturist and literary giant, and Ivan Bunin, winner of the 1933 Nobel Prize for literature. She first met Ernst Junger in 1943 while he was serving as an officer in occupied Paris. Junger was an acquaintance of Wilhelm Blanke, a German officer courting Banine and secretly helping the French resistance. Blanke urged Banine to send a copy of Nami to Junger, who was about to depart for the Eastern Front, but shortly before the allied landings in Normandy Blanke was denounced and later tried and hanged, which Banine wouldn’t discover until after the war. Her friendship with Junger would last for almost 50 years:

She dealt with his literary affairs in Paris, translated his letters and articles into French and wrote three books about him, wrote Mr Abutalibov.

She met Ivan Bunin three years after Junger, in 1946, and was drawn to his stateliness and elegance, later recalling: Bunin wore arrogance like a toga to show the difference separating him from ordinary mortals.

Several of Bunin’s works, River Restaurant and Selected Poems, sat inscribed with personal dedications to Banine alongside those of Anton Chekhov and Lev Tolstoy on the single bookshelf in her tiny studio flat at 40 Rue Lauriston, where she lived for over 50 years.

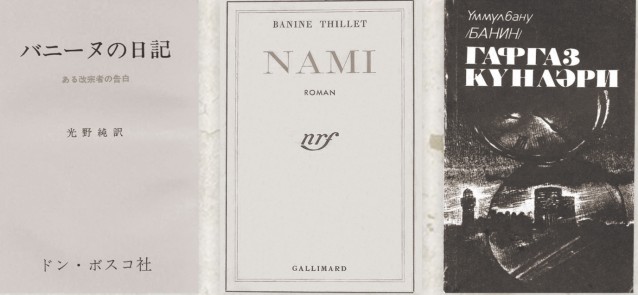

Banine wrote in French and her works were translated into numerous languages. Pictured here from left to right are a Japanese translation of I Chose Opium, a French edition of Nami and the 1989 Azerbaijani translation of Caucasian Days

Banine wrote in French and her works were translated into numerous languages. Pictured here from left to right are a Japanese translation of I Chose Opium, a French edition of Nami and the 1989 Azerbaijani translation of Caucasian Days

A forgotten writer

Banine’s heritage is purely a literary one, wrote Mr Sturmer, who continues to promote her life and work. She was poor, though protected by rich and influential friends and received social help from the French state.

When I met her, Banine had not published a book for 17 years, except the last version of “Jours Caucasiens” [Caucasian Days. Ed.], for which she paid herself the printing. She was quite forgotten for French or any other readers. She still is not famous, I fear to but must say this.

Her later years were spent reading in her apartment, which she left only to visit nearby friends, or receiving guests who were often more interested in the work of Ernst Junger than hers. But Mr Sturmer was different: I was more interested in her than in Ernst Junger, he said. Otherwise, as he recalled:

Banine spent a lot of time, as she said to me, in her armchair, near the window, dreaming as a cat in the sun. She had difficulty in finding sleep. I was allowed to call her up to midnight. She listened a lot to the radio, too. She liked classical music. In her youth, she had been a fine pianist, but there wasn’t any piano left.

National icon?

Towards the end of her life Banine continued to recall certain streets in Baku as well as the gardens of the Asadullayevs’ family dacha in Mardakan, but Mr Sturmer cautions against turning her into an Azerbaijani national icon:

Banine considered France her home. After all, she spent only 19 years in Azerbaijan and much more than 60 years in France. Living in France meant to her liberation. The Azerbaijan of her memories was the Russian Empire and the family, then the Bolshevik Revolution, prison for her father, then a marriage she did not wish for but which helped to free her father from prison. Azerbaijan for her, a very young girl, was: “I have no choice! I have to follow the choice of my father…”

In reality, her cultural identity blended diverse influences, as she emphasised in an interview in 1947:

I have experienced the most diverse cultures: a German governess replacing my mother, the Islamic surroundings in which I was born, the Russian grip in which we were the tartar others, the rebellious subjects, Tolstoy and Dostoyevskiy which I read when I was playing with dolls… I should mention the biggest of all, the French influence.

Whether due to or despite this complex identity, the turbulence of her youth, the two unhappy marriages (she married again in 1935, to a French architect almost 20 years her senior, but the marriage only lasted a few years) and literary ups and downs, Mr Sturmer alluded to an aura of sadness and depression that accompanied Banine’s later years. Far from the glitz and glamour of Baku’s turn-of-the-century oil industrialists, the reality of this soulful French-Azerbaijani writer, he wrote,

was the life of a mostly unhappy woman who tried to make her way in this hostile world, to find love or friendship or a little bit of fame, some recognition.

She was a writer.

Banine died on 23 October 1992 in a hospital in the 16th arrondissement of Paris, having never managed to revisit Azerbaijan. Despite her grand literary heritage, she remains relatively undiscovered in her native land - Caucasian Days was only published in Azerbaijani in unedited form in 1992. TEAS Press hopes to change this with an English translation soon, but for now what follows is a short extract of her most famous novel to whet the appetite...