Mammad Amin Rasulzade was Chairman of the National Council of the Azerbaijani Democratic Republic (1918-20), which emerged following the dissolution of the less-remembered Transcaucasian Federation (1918). This fleeting attempt to unite the Caucasus republics lasted for only a month, however the idea of an independent Caucasus Confederation lived on in the hearts and minds of the political émigrés such as Rasulzade who escaped the Bolshevik regime.

In the following article, Ramiz Abutalibov, a former Azerbaijani diplomat and author of several books on Azerbaijani emigration, analyses Rasulzade’s lasting influence on the idea of uniting the Caucasus.

The idea of a moral and political unification of the peoples of the Caucasus that emerged in the unique geopolitical circumstances of 1918 has its own dramatic history, which is mirrored in the lives and work of the politicians of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic (ADR). Many of them believed that the best way to guarantee the future and freedom of the Caucasus was to unite all the republics into a confederation. Only having united the resources of their states could the peoples of the Caucasus strengthen their security against external encroachments.

According to the historian Aydyn Balayev, Rasulzade was a strong supporter of the Caucasus Confederation from the start. Nevertheless, we will try to establish based on the facts: when did this happen? What were the reasons? And what was the significance of his activity?

The short-lived TDFR

World War I brought about great changes in the world and shook the foundations of empires, including the Russian one, to the core. In Petrograd in February 1917 the revolution began that ended the tsarist autocracy. Rasulzade greeted the overthrow of the Tsar with enthusiasm; he took part in revolutionary events and having entered this stormy whirlpool became a noteworthy politician.

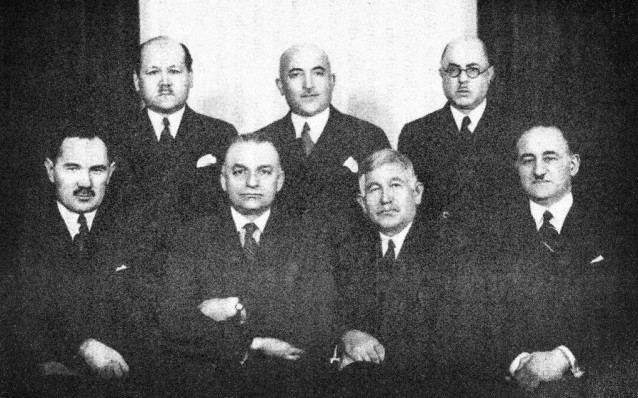

The leaders of the Caucasian and Turkish peoples of the Prometheus Front in Warsaw in the 1920s. From left to right, sitting: Mammad Girey Sunsh, Jafar Seydamet, Ayaz Iskhaki, Mammad Amin Rasulzade; standing: Mustafa Chokay, Mustafa Vekilli, Tausultan Shakman

The leaders of the Caucasian and Turkish peoples of the Prometheus Front in Warsaw in the 1920s. From left to right, sitting: Mammad Girey Sunsh, Jafar Seydamet, Ayaz Iskhaki, Mammad Amin Rasulzade; standing: Mustafa Chokay, Mustafa Vekilli, Tausultan Shakman

Rasulzade was soon elected a minister of the Russian Constituent Assembly, which was dissolved in Petrograd in January 1918 by the new authorities – the Council of the People’s Commissars – who were dissatisfied with the team of elected ministers. Following this, on 22 and 23 January 1918, a meeting took place in Tiflis of the Trancaucasian ministers elected to the Constituent Assembly, which had ceased to exist. Here they decided to assemble their own legislative body – the Transcaucasian Seym, the first session of which was held on 23 February in Tiflis. The Transcaucasian Seym announced the secession of Transcaucasia from Soviet Russia in March 1918, and declared the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic (TDFR) in April that year.

Many of them believed that the best way to guarantee the future and freedom of the Caucasus was to unite all the republics into a confederation

The Musavat party faction in the Seym, which was led by Rasulzade, was the only faction that from the very beginning of the all-Caucasus parliament consistently supported Transcaucasia’s declaration of independence and the creation of the TDFR, which constituted three national and territorial autonomies – Azerbaijani, Armenian and Georgian. Speaking on 20 February 1918 at the Seym, Rasulzade emphasised that:

The Transcaucasian Seym is the Constituent Assembly and as the Constituent Assembly it must work on developing a constitution for the Trancaucasus.

Rasulzade was convinced that only recognition of the Seym as the Constituent Assembly could bring the peoples of the Caucasus to an amicable, federative and united way of life.

However, at this stage both the great majority of Georgian and Armenian ministers in the Seym and the other Azerbaijani factions were not ready to irrevocably sever all ties between Transcaucasia and Russia. In the early days of the Seym the idea of Trancaucasian independence advanced by the Musavat faction was only supported by the Georgian national democrat Georgiy Gvazava, who also proposed: the secession of Transcaucasia from the Russia represented by Lenin and his comrades.

During a session of the Seym on 9 April 1918, Rasulzade seemed to publicly support the idea of uniting the Caucasus:

Transcaucasia must be independent. This independence is becoming a necessity. In order to live on friendly terms, for the peoples of Transcaucasia to live united and take advantage of the spoils of freedom gained through the revolution, it is essential to declare independence… If we declare our independence not for fear but for conscience, I hope that this independence will serve as a strong bonding of the peoples of Transcaucasia, and that the democracy of Transcaucasia in terms of its peaceful work and co-existence will acquire the benefits that will lend it the strength and energy to defend its freedom from any form of encroachment.

Yet, as is traditionally believed in historical literature, the interethnic aspirations of the Azerbaijanis, Armenians and Georgians served as one of the main reasons for the short existence of the TDFR and the Transcaucasian Seym. At any rate, on 26 May 1918 it was voluntarily dissolved, after which Rasulzade was one of the initiators of the declaration of the Azerbaijani [Democratic – Ed.] Republic on 28 May 1918 and elected chairman of its National Council.

Idea of unification rises again

The reasons for the fall of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic were deliberated over in exile by those who were direct participants in what happened in Azerbaijan and who knew the situation in the country very well. All this makes what was published in emigration, and what remains in émigré archives and was not meant for print, especially important for the modern analyst.

The idea of unification arose once again with renewed vigour in émigré circles

These numerous materials of the most diverse nature have led many authors to the rightful conclusion that the main reason for the fall of the ADR lay in the absence of unity in the Caucasus, the absence of solidarity between the young Caucasian states and in the unfulfilled concept of the Caucasian Confederation. And this was despite the fact that great effort was made through the diplomacy of the young Azerbaijani republic to strengthen relations with other states, in particular with its neighbours. As Rasulzade wrote, forming excellent relations with its neighbours was its ultimate wish. Of the ADR’s Christian neighbours, relations with the Georgian Democratic Republic were the most amicable.

Following the occupation of the Georgian Democratic Republic by the Red Army in February-March 1921 and the establishment of the Bolshevik regime across the whole of the Caucasus, the idea of unification arose once again and with renewed vigour in émigré circles, insofar as one of the reasons for the political collapse of the Caucasian republics was seen as the absence of unity between them.

Political émigrés began to realise more fully the mistakes and missed opportunities of 1918-1921. The understanding that the long-term interests of the peoples of the Caucasus had fallen victim to narrow-minded national egoism occupied the minds of émigrés ever more. The foreign policy factor had a role here too. Drawing the global public’s attention to the Caucasus issue by considering the economic interconnectedness and shared resources of the region would have been more beneficial than considering the Caucasian republics separately.

The Caucasus Confederates Committee (CCC) was created in Istanbul in October 1924 with financial support from the Poles and was joined by representatives of the political organisations of Georgia, Azerbaijan and the North Caucasus: from Azerbaijan, ministers of the ADR, Khosrov-bek Sultanov, Abdul Ali-bek Amirdzhanov and Akber Aga Sheykhulislamov; the North Caucasus was represented by the Ingush, Vassan-Girey Dzhabagiev, the Ossetian, Alikhan Kantemir, and the Circassian, Khaytek Namitokov. At the same time, in Paris in October and November 1924 representatives from the Caucasus decided to create a union of the three Caucasus republics in the form of the Caucasus Confederation.

Azerbaijani diplomatic staff at work. From left to right: Alimardan bey Topchubashi, Abbas bey Atamalibeyov, Rashid Topchubashi, Sefvet Malikov-Zardabi

Azerbaijani diplomatic staff at work. From left to right: Alimardan bey Topchubashi, Abbas bey Atamalibeyov, Rashid Topchubashi, Sefvet Malikov-Zardabi

A special commission was formed to draw up a constitution for the future state. In order to unite the diplomatic work abroad with the leadership of the fight to liberate the peoples of the Caucasus it was decided to create the Caucasus Committee, whose members included the Chairman of Parliament of the ADR, Ali Mardin Topchubashi, and Jeyhun Hajibeyli; from the North Caucasus – Head of the Mountainous Republic Abdul Medjid Chemoev, I.Gaydarov and Heydar Bammatov.

In 1925 the Caucasus Committee in Paris addressed the Caucasus Confederates Committee in Istanbul with an offer to create a united Caucasus Committee. The negotiations that followed over the course of a year concluded with the creation of the united Caucasus Independence Committee (CIC) in Istanbul on 15 June 1926, whose members included Rasulzade and Mustafa Vekilov from Azerbaijan; from the North Caucasus – the grandson of Imam Shamil, Seid-bek Shamil, and Alikhan Kantemir; from Georgia – Noy Ramishvili and Nestor Magalashvili. Soon however, due to the position of the Turkish leadership, which did not want to aggravate relations with Moscow, the decision was taken to transfer the committee’s work to Paris.

Prometheus & The Promethean Front

The magazine Prometheus (Prometey) was also first published in Paris in 1926. Prometheus was the publication of the Caucasus Independence Committee and the mouthpiece of political émigrés from the Caucasus, Ukraine and Turkestan, which brought together a number of well-known émigré figures, including Rasulzade.

Political émigrés began to realise more fully the mistakes and missed opportunities of 1918-1921

The idea of the Caucasus Confederation was promoted in Prometheus as well as in the publications of other Caucasus émigré organisations. The creation of the Caucasus Independence Committee and its publication, Prometheus, ushered in ‘The Promethean Front’ – a united movement of representatives of all the non-Russian nations of the Red Empire whose position was to recover the independence of their states, created with the support of the Polish government of Jozef Pilsudski.

Rasulzade also devoted a lot of time to promoting the idea of the confederation in the books he published, as well as in publications belonging to other Caucasian nations. For example, in a book published in Russian in Paris in 1930 entitled Pan-Turkism in Relation to the Caucasian Problem, whose main criticism was directed at figures from Armenian political parties and organisations who were against uniting the Caucasus, Rasulzade wrote that, from the very beginning of the Azerbaijani Democratic Republic, Azerbaijani political figures had supported the idea of uniting all the peoples of the Caucasus in a single confederative state.

Also in 1930, an article of his called Under the Slogan of Caucasian Unity was published in the magazine Mountaineers of the Caucasus. In it he highlighted that:

uniting the peoples of the Caucasus and full awareness of the need to make the idea of an independent Caucasus Confederation a reality – this is the reliable guarantee of our ultimate victory,

and called for the peoples of the Caucasus to unite and raise the flag of a united Caucasus alongside the individual national flags.

Caucasus Confederation Pact (1934)

1. The Caucasus Confederation will guarantee the national independence and territorial sovereignty of the republics and will act in the name of all republics as the highest state entity with a common political apparatus and customs borders;

2. The foreign policy of the republics in the confederation will be carried out by the established representatives of the confederation;

3. Defence of the borders of the confederation is undertaken by the army, consisting of the armies of the republics in the confederation, and this army is under the command of the confederation;

4. Any conflict that might arise between the confederate republics that is not resolved by peaceful means is transferred for resolution by obligatory arbitration or to the highest court of the confederation, whose decisions must be fully implemented.

The fifth clause provided for the formation of a commission of experts who would draw up the future constitution of the Caucasus Confederation, and the sixth clause left a place open for the Armenian Republic. The pact was signed by Mammad Amin Rasulzade and Ali Mardin Topchubashi from the ADR; Mamed Girey Sunsh, Ibrahim Chulik and Tausultan Shakman from the North Caucasus; and by Noy Zhordania and Akakiy Chkhenkeli from Georgia.

After the pact was signed, the question arose of organising a united centre: a prototype of the future government of the Caucasus Confederation, and in the meantime an operational administrative body. At the Promethean Movement conference in Paris in January and February 1935 the Caucasus Independence Committee was discontinued and the Caucasus Confederation Council (CCC) was created in its place. This functioned as the all-Caucasus government in exile, whose decisions were mandatory for all its members. The council was made up of four representatives from each national centre. A presidium was also created, consisting of the three most authoritative representatives of Azerbaijan, Georgia and the North Caucasus – Rasulzade, Noy Zhordania and Mamed Girey Sunsh. Later, in order to further centralise the activity of the Caucasus Confederation Council the position of chairman was introduced and held by Akakiy Chkhenkeli at the end of the 1930s.

A document adopted at the conference entitled The Caucasus Question and Russia defined the authority and aims of the ruling body of the Caucasus Confederation. The main area of its activity was determined as preparing the Caucasus nations for the creation of independent republics and their subsequent unification within a confederation. During the discussions and decision-making at the conference special emphasis was made on the need to transfer the core of the work directly to the Caucasus. The conference’s participants believed that only in so doing would it be possible to bring to an end ‘‘the Russian occupying regime in the Caucasus.’’

Musavat & Cauacsian unity

In August 1936 a Musavat party conference was held in Warsaw and served as an important step forward in terms of refining the ideological and political foundations of the party’s programme. The party’s New Programme Principles were adopted there and in many respects substantially differed from the previous Musavat programme. According to this document ‘musavatism’ was qualified as:

Azerbaijani patriotism, committed to the ideals of freedom, republicanism, national independence and organically linked to the high ideals of universal human civilisation and the great Turkic culture.

The party’s main aim was declared as: to rid Azerbaijan of the Russian occupation and restore the independence of the country.

Moreover its commitment to Caucasian unity was highlighted once again in The New Programme Principles, which stated:

with the aim of achieving national independence and its future protection from numerous threats, Azerbaijan must reach political, military and economic unity with the other republics of the Caucasus on the basis of the pact regarding the Caucasus Confederation of 14th July 1934.

Mammad Amin Rasulzade and the leaders of the Prometheus movement bidding farewell to Alimardan bey Topchubashi

Mammad Amin Rasulzade and the leaders of the Prometheus movement bidding farewell to Alimardan bey Topchubashi

The Warsaw conference introduced the theme of the Caucasus Confederation as a central idea in the ideology of the party. According to Rasulzade’s report, it was stated at the conference that, according to its ideology and ultimate goal, the Musavat party was a Turkic party. But, despite its Turkic ideological specificity, it never refuted the reality of uniting the Caucasus peoples into one political whole. On the contrary, serving as a guarantee of lasting peace in the East and acting as a barrier against Russian penetration into the South might serve as the decisive factor in the struggle against ‘‘the age-old enemy.’’

Ever more new documents are appearing that lead to the conclusion that the ideological legacy of the émigrés is indeed very profound and multi-layered in terms of analysing the 23 months of Azerbaijani independence

To conclude, the political life of Azerbaijani emigration would seem to have been sufficiently explored over recent years. However, ever more new documents are appearing that lead to the conclusion that the ideological legacy of the émigrés is indeed very profound in terms of analysing the 23 months of Azerbaijani independence, the reasons for the ADR’s fall, events at the time of the revolution, the upheaval of the civil war and the consequences of foreign invasion and armed intervention in Azerbaijan. Everything that happened with our motherland in the first half of the 20th century.

About the author: Ramiz Abutalibov is a former Azerbaijani diplomat and author of books and articles on Azerbaijani history and émigré life in the 20th century.