Following Sheki’s selection as the Turkic Capital of Culture and Art for 2016, the region is likely to play a greater role in promoting Azerbaijani and Turkic culture at home and abroad. Local journalist Gunel Manafli tells Visions readers what much-loved Sheki is all about.

This city of quiet beauty and clean mountain air lies surrounded by the Caucasus Mountains and its inhabitants differ in their peculiar manner of speech. It resembles an earthly paradise and makes you smile just by hearing its name - Sheki. There is no quarrelling or frowning here, everyone tries to be sociable and cheer each other up by telling jokes. It is considered shameful not to know jokes in Sheki because the city is, among other things, famed for its humour. Founded more than 2,700 years ago, Sheki is one of the most ancient settlements of Azerbaijan, located on the southern slopes of the Greater Caucasus Mountains, 370km northwest of Baku. Travelers and visitors who come here leave unwillingly because of the clean air, picturesque landscapes and friendly inhabitants.

Sheki has long been popular with tourists for its favourable location and ancient historical monuments. So it is no great surprise that this year TURKSOY (the International Organisation of Turkic Culture) declared Sheki its Capital of Culture and Art, thanks to its original features and rich local culture. TURKSOY was founded in 1993 by the ministries of culture of Turkic states and autonomous regions to create unity in the spheres of art and culture. By appointing a cultural capital each year the organisation aims to bring together artists and intellectuals and facilitate cultural integration within the Turkic world.

Sheki’s selection was celebrated on 29 April with a grand festival in the gardens of the historical Khan’s Palace, which hosted folk dancing, a handcrafts exhibition and press awards ceremony. Sheki is no stranger to staging festivals and many foreigners take part each year. The Silk Way Festival features memorable performances of world music and was held for the seventh time this summer, with musical groups from Azerbaijan, Turkey, Japan and Poland. The first Sheki Theatre Festival was held in 2014, within the framework of the Azerbaycan teatrı 2009-2019-cu illerde (Azerbaijani Theatre 2009-2019) programme, while the Naghara (Drum) Sheki International Festival of Percussion Instruments debuted here in the Caucasus last year. Another favourite is the International Festival of Sweets, which traditionally begins on 20 July. Sweets (firni, xashil, sweet pilaf, milky kasha, etc.), pastries (baklava, feseli, gatlama, zilviyye, umadj halvah, etc.) and confectionery (noghul, nut halvah, semeni halvah, etc.) are exhibited from around the country and dished out by representatives of the different peoples and regions of Azerbaijan, each dressed in national costume to evoke their particular regional atmosphere.

Along with being the Capital of Culture 2016, Sheki is twinned with several other cities: Giresun (Turkey) since 2001, Colmar (France) since 2014, and Gabrovo (Bulgaria) since 1980. In such a way, Sheki plays an important role in promoting Azerbaijan throughout the world.

Passing the kelegayi through a ring

The city is also considered the country’s capital of handcrafts and the artistic products made here are not produced in any other region of Azerbaijan. Local artisans have managed to preserve their secrets until today, passing them down from generation to generation. An example of one such skill is pottery: household objects and kitchenware made of clay. Products made here are sold locally and abroad. Yet the region is probably best known for something else.

As Sheki is located on the old Silk Road, silkworm breeding has been the main industry here for centuries. Mention silk in Azerbaijan and we immediately think of Sheki. The process of transforming mulberry leaves into silk is very delicate. Before becoming silk, the silkworm passes through several stages, to produce very fine silk, an example of tenderness and wonderful beauty. A favourite of guests and tourists is the kelegayi headscarf made with Sheki silk. There is a special way to test the kelegayi’s authenticity: if the kelegayi, whatever its size, passes through a wedding ring then it is made from genuine Sheki silk.

Sheki is also famous for its embroideries. In the 19th century the region was the centre of tekelduz embroidery, which is made using colour silk threads and is normally embroidered on velvet or woollen fabric; only the tekelduz in a gobelin style is embroidered on linen. Tekelduz embroidery is an ancient Sheki art and means to make with one hand. In ancient times, only men would embroider it but today women do too. It was used to decorate things like women’s clothes, pillows, covers and bathroom rugs and the designs often featured the flora and fauna of Azerbaijan. It is not an easy craft - one composition can take three or four months. Red, black or dark blue velvet is sourced locally or from abroad. First the artisan draws the outlines of the embroidery on the fabric stretched tautly across a machine and then fills in the middle. The needle used is called a garmaj.

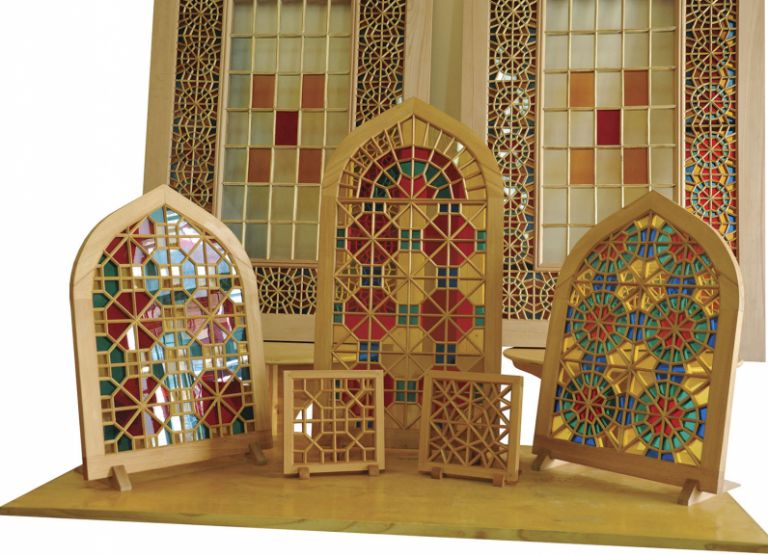

Shebeke – only in Sheki

The subtlest, most beautiful shebeke - locally produced, multi-coloured stained glass - in the world decorates the Palace of Sheki Khans. You will be unlikely to see such stunning shebeke anwhere else in the world. It is manufactured with great dexterity and the main feature of this art is that the shebeke mosaics are put together without glue or nails. The patterns are formed of geometrical figures, the round, polygonal and star-shaped forms being the most important. An average-sized shebeke mosaic consists of 5,000 wooden and glass details. 10 to 15 steps are required to produce one detail, which means performing some 50,000 steps overall to produce an average-sized shebeke. This can take up to five or six months.

The round-form shebeke made by Huseyn Hadjimustafazade in Sheki is unique. According to him, the distinguishing feature of his shebeke is that the details are curved and truncated rather than straight. The wooden frames around shebeke are generally made from oriental plane trees.

A 300-year-old hotel

Caravanserais built along trade routes used to function as guesthouses. As Sheki was a city of trade and crafts a set of caravanserais was built here, but only two of the five large caravanserais that functioned in the 18th and 19th centuries have reached modern times. These are the Yuxarı Karavansaray (Upper Caravanserai) and the Ashagi Karavansaray (Lower Caravanserai). Today the Yuxari Karavansaray functions as a hotel. Entering feels like travelling back three centuries, it feels as though this mysterious place has kept even the smell of the past. The two-storey building with its deep basement was built at the end of the 18th century. The eastern architectural style emphasizes its antiquity and beauty. The lower row of rooms on the first floor is the basement, where trading merchants and guests would store their goods. The old walls, the pool decorated with ancient ornaments, the stone steps leading to the second floor from the wide courtyard - all this carries us back through the centuries.

The Ashagi Karavansaray is currently being restored. At 12 metres high on the street side, 10 metres on the east and west sides, it is larger than the Yuxari Karavansaray. It has an area of 8,000m², 242 rooms and four entrance gates and reflects the style of Sheki’s architects. The main facade overlooks the river, giving a sense of silence and freshness. A pool sits in the centre of the courtyard. In times gone by this building, would hospitably open its gates for merchants and strangers, but would just as quickly turn into an impenetrable fortress when closed.

Sheki Khan’s Palace

There is a story in every detail and every corner of the Palace of Sheki Khans, considered the brightest example of medieval Azerbaijani architecture. It was built in 1763 by Huseyn khan, the grandson of Haji Chelebi khan. Thousands of small pieces of glass were used to produce the shebeke window mosaics, fitted together without glue or nails. It was with reason too that the palace was built in the upper part of the city: it was intended as the summer residence of the khan, the moderate heat and clean mountain air in the higher part of the city turning it into a paradise in the hot summers. Not only men but also women could unwind on the palace’s double balconies, which were closed at either end to maintain privacy.

The 300-year-old oak and plane trees growing in the yard add a sense of mystery - to touch them feels like coming into contact with 300-400 years of history. Inside the palace the multi-coloured patches of light beam through the shebeke, playing with the sunshine and pleasing the human eye, the refined drawings on the ceilings and the various patterns on the walls - all this makes you wonder about the richness of the imagination and talent of the old Sheki masters.

Piti – once a dish for servants

Piti represents the best of Sheki cuisine and no visitor to the city should leave without having tasted it. It is unique in terms of the peculiar way that it is prepared and eaten. The dish has a long history too. Piti contains a lot of fat and since it gives people energy, it used to only be given to servants to keep them strong. In ancient times piti was first prepared by a man named Horuzoglu. Legend says that a high-ranking official sent a man to the dining room to fetch piti for his guests, but the cook refused to serve it, arguing that he couldn’t open the piti pot until it was absolutely ready. After all, preparing this dish requires careful observance of all the rules of Sheki cuisine. Piti is prepared in small clay jugs; a dish not prepared in one of these can’t be called piti.

Usually Sheki’s cooks begin preparing piti in the evening. It is traditionally cooked for five or six hours on a weak fire and served hot the following morning. The process of eating is also interesting. First, bread is crumbled onto a plate and then the liquid from the clay pot is poured on top, leaving just a little liquid at the bottom of the pot. Then an onion is cut into four large pieces. The second stage begins as soon as the first comes to an end. This time the peas and meat are removed and seasoning is added. Then the contents of the plate are squashed with a fork and eaten with bread and onion. Sheki’s residents do not recognise piti cooked or eaten in any other way!

Mysterious roots of Sheki halva

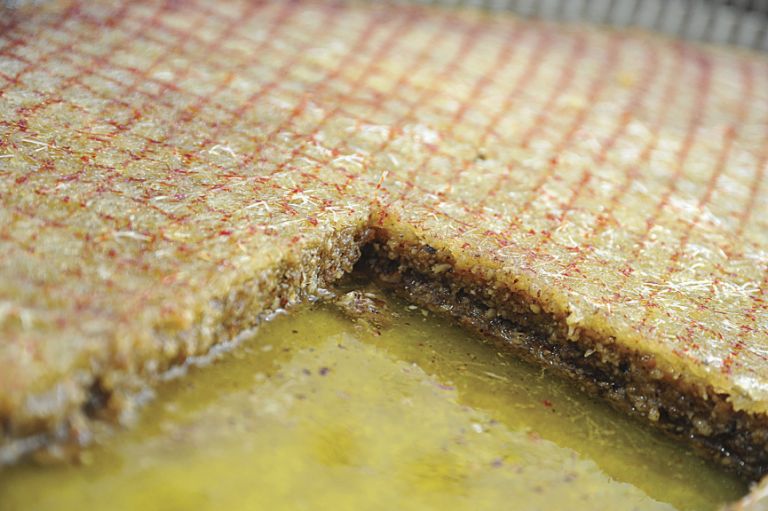

The name Sheki conjures instant thoughts of its sweets and in particular its halva, which despite the similarity is not called bakhlava here. There are various opinions about the origins of Sheki’s halva. Some claim that the recipe first appeared in the period of the Sheki khanate; others say it was invented by locals. Over sixty shops producing and selling halva function in the city today, the majority of which belong to local producers. Real Sheki halva is cooked according to ancient recipes passed down from previous generations. One of the shops in which the profession has been handed down is Aliakhmed Shirniyat Evi (Aliakhmed’s House of Sweets). Hosrov Gafarov, its manager, claims that he inherited the knowledge and skills from his father. According to him, making halva is not something that anyone can do - halva cannot be prepared at home.

Ilgar Rustamov has been making halva at the Aliakhmed Shirniyat Evi for years and says that to prepare halva requires following certain rules. Sheki halva is produced from rice flour, from which a liquidy dough is made. This dough is then poured through a copper funnel into copper baking sheets. (Halva must be prepared in copper ware). 10-12 layers are made and placed on top of one another. The surface is evenly covered with a layer of groundnut. Then five more layers are added and the resulting surface mixture is colourised with saffron and baked for about 15-20 minutes. Finally, syrup is prepared from granulated sugar and evenly poured over the halva.

These are just some of the many wonderful beauties and delicacies in Sheki. It is not without reason that they say a picture is worth a thousand words. 2016, Sheki’s year as the capital of Turkic culture, is the ideal time to visit.

About the author: Gunel Manafli is a Baku-based journalist originally from Sheki.