Pages 40-59

by Fiona Maclachlan

A few hours separate the clean calm air of Azerbaijan’s mountain villages from the dust and bustle of overcrowded Baku. For a break from hectic city life, I will take you first to the fabled village of Xinaliq, then Lahij (Lahic), probably Azerbaijan’s most popular village for tourists and, finally, forgotten Saribash.

by Fiona Maclachlan

A few hours separate the clean calm air of Azerbaijan’s mountain villages from the dust and bustle of overcrowded Baku. For a break from hectic city life, I will take you first to the fabled village of Xinaliq, then Lahij (Lahic), probably Azerbaijan’s most popular village for tourists and, finally, forgotten Saribash.

Xinaliq - the fabled village

Xinaliq is Azerbaijan’s highest mountain village, approximately 2,250 metres above sea level. Xinaliq is in a stunning location not far from Shahdag, Azerbaijan’s highest peak, in the southeast ridge of the Caucasus mountains. It has an ethnically distinct population with their own unique language, habits and culture. But they also speak Azerbaijani or Russian.

Renowned for its remote and beautiful location, Xinaliq has long attracted visitors keen to experience the stunning high Caucasian mountain scenery. Tales of Ateshgah, the fire that continuously burns on the nearby mountainside, also add to its unique appeal. However, Xinaliq is inaccessible except in fine weather.

Until recently the road was so poor that only 4x4s could make it there, even in high summer. A year or so ago the road was dramatically improved, and the surface was covered in tarmac. A few stretches, which were being worked on when. I went, can still cause difficulties for normal cars but there is no doubt that access is very much easier. However, the weather and remote location have not changed, so do take care when planning your own trip, and expect snow except in the middle of summer.

The journey to Xinaliq is as dramatic as the village is remote, so take your cameras and be prepared to enjoy the trip of a lifetime.

To reach Xinaliq from Baku, first drive north to Quba (Azerbaijan’s famous apple growing region). Continue north and west through Quba into the mountains. To make sure you’re on the right road, follow signs (or ask) for Qachresh village. Then on and into the stunning Cloud Catcher Canyon.

The road route through Cloudcatcher is fantastic and the journey towards Xinaliq is worth making for this alone. Cloudcatcher Canyon, Mark Elliot’s name for this place, is a deep narrow steep-sided rocky canyon, with a small river running through it, and the scenery is particularly spectacular. Open the sunroof and see the cliffs soaring up and up, overhead, it’s breathtaking! Watch the buzzards wheeling overhead. A couple of steep hairpin bends and the road takes you up out of the gorge, and along to where you can look down to the right and glimpse the depths of Tolkien’s Chasm (another of Mark Elliot’s apt names). Just beyond is a grassy place to park, stretch your legs, and take in the glorious panoramic scenery. Mark Elliot describes this spot as the best view anywhere. (Mark Elliott, Azerbaijan with Excursions to Georgia, Trailblazer Publications, 2004)

Back on the road, the small village of Jek is the first place you come to. Like many places in Azerbaijan, new buildings, schools etc. are appearing. But Jek is appealing, with very neat and tidy homesteads on a grassy hillside. Drive onwards through wide open grassy mountain and river scenery, gradually climbing higher above the tree line, with the mountains in the distance still with last winter’s snow.

The grassy meadows are full of wild flowers and teeming with noisy insect life. Get out of the car and listen! Sheep and cattle graze on the healthy vegetation, and you pass the occasional shepherd on horseback.

And finally you reach Xinaliq, and the end of the road. The village initially looks scruffier than I had imagined. It rises up the hillside to the right of the road, overlooking the amazing open panorama of sweeping, majestic hills and mountains all around. We pulled in to the left, into what looked like a parking area.

Below and to the left, a brand new school nears completion.

We were met by Rauf, a son of Badal mentioned in Mark Elliot’s Azerbaijan book. Best not leave your car here, he said, lest the children damage it. A number of young children bounded excitedly around, looking as if butter wouldn’t melt in their mouths. We could hardly believe they would damage a guest’s car. Nevertheless we felt obliged to take up Rauf’s kind invitation to park the car up by his house, and then he took us to the museum for a look around.

Two manats each to get in for a foreigner, and one for a local. Our new driver was embarrassed at the discrimination, but we are used to it. However on this occasion we all ended up paying as locals.

Village museums in Azerbaijan hold a wealth of very local information and I am sure that they will be modernised in due course. Museums in Baku, and to an extent in the bigger towns such as Qabala, are currently receiving lots of love and attention; meantime these village museums lie neglected and dusty. Information about the exhibits is sadly lacking which is frustrating for the interested visitor. After the museums are revamped, people will be able to get a much better understanding of life here - I look forward to it. This is especially important because villagers love to show guests their museum.

Out of the museum, and looking around us we saw two young girls aged about six and eight, dressed in colourful mismatched clothing, standing side by side. They were doing the family washing by hand out of doors, in wide metal shallow bowls. They stared at us and possibly wondered...

In turn, we stared at them, guiltily. Feeling guilty for staring, and guilty for children doing the work of adults, and guilty that our own children can barely hand-wash a handkerchief (if they could even recognise such an item in today’s "disposable" society).

And yet here we were, in the highest mountain village in Azerbaijan, surrounded by simply stunning scenery, feeling just a little like peeping toms. Walking though the village is like walking through a film set. Most of the houses are immaculately kept, and the "country pancake" dung pies are stacked ever so neatly, ready for use for winter heating. There are no trees which can be used for firewood in the empty grassy landscape. The stonework is dark grey, a contrast to the usual golden stone used in Azerbaijan. The paintwork is mostly white and blue. Even some hens and ducks are daubed with blue paint, I guess to claim ownership. The houses are staggered up the hillside, adjacent to one another, so that the flat roof of one is the terrace of the next. Residents stand on the roof tops/terraces and watch the world go by, and us too.

Then into Rauf’s home for tea. Rauf explained their life in Xinaliq. He is married to a beautiful wife and they have two beautiful children, a handsome solemn young boy and a charming girl, quick to laugh and have fun.

We sit on the floor on colourful comfortable cushions and chat about this and that, the age people in the village live to, that sort of thing. Words and language feature too, because Xinaliq people have their own tongue, handed down over the generations.

Selling a sheep gets them 60, maybe 80-100 manats. Selling a two-year-old cow gets them 300 manats. The animals are taken alive to Quba and some even end up in Baku restaurants. The villagers take it in turns to look after the animals, on a rota, street by street. There are about 300-350 homes in Xinaliq.

Trips for tourists bring in more money. Rauf says he takes 30 manats per person (max 10 people) for a guided horseback trip to Suvar/Laza, which will take five to six hours. And 260 manats (total, not per person) for an 11 to 12 hour trip to Qabala, again on horseback. I wonder to myself, could I do one of these trips? Would I be up for it? I’m tempted, definitely tempted. And what about the new road, I ask, do they like it? I imagine that it will make the journey more comfortable for them, and easier. But instead I get the impression that they are indifferent. We only go to Quba once every eight months, Rauf tells us. Then we buy everything we need. Things like tea and sugar, for example.

But judging by the visitors’ book in the museum, the new road certainly brings people to Xinaliq, even if the local people have little desire to leave.

The quote on the wall in the museum, roughly translated, says it all:

"When springtime comes to Xinaliq, I wouldn’t swap this village for a hundred Parises or a thousand Londons."

A wedding was to take place that afternoon, we were told. A local girl was to marry a boy from Quba. And yes, she would go to live in Quba with him. I wonder about the change of lifestyle ahead of her.

And then I wonder how it works for Xinaliq boys finding a wife from outside Xinaliq - what would make a young girl want to make that move? Whatever the answers are, or may be in the future, Xinaliq and its people have until now, uniquely, survived. Will it continue? The ubiquitous satellite TV dishes offer Xinaliq residents a window onto the world far from their day to day existence. Will they be tempted away?

In the 1970s, according to Mark Elliot, the ground on the nearby hillside was terraced and laboriously farmed. But not now, apparently, it’s not worth their while. Perhaps for the first time in history, the people of Xinaliq have a real choice.

Lahij - a tourist gem

Many years ago there was a city of 36,000 people called La. One day there was a very big earthquake and La was flattened. It became nothing, and so was called La-hec. Hec is Azerbaijani for nothing, or zero.

In time people came to live in the settlement again, and so it could no longer be called "nothing", and the modern name of Lahij came about.

Today’s Lahij is a remote mountain village, 1,629m above sea level, comprising some 2,000 residents. You will find it in the Ismailly Rayon (district) of Azerbaijan, and you can only access it from the road which connects Shemakha to Ismailly. Turn off at the big signpost, which gives clues to the support and international attention this village is receiving, and travel up the 19km dirt road which winds up the Girdimanchai river gorge. Ice and snow cut off Lahij for weeks at a time in winter.

The drive up to Lahij is as stunning as it is dangerous, with the winding dirt road somehow cut into the vertical cliff face that plunges down into the valley hundreds of feet below. The strata of the sheer rock alternate between horizontal and vertical. It’s a dizzying ascent. Rocks fall from above, and even in fine weather the route is regularly "ploughed" to keep it free of soil and rocks and so passable. Almost unbelievably, several "vintage" buses a day go up and down this road, trundling villagers and their goods up and down.

Isolation has made Lahij a very a typical Azerbaijani village: Lahiji, a dialect of old Persian, remains to this day the primary language in Lahij. The local people converse in it all the time. They have no alphabet for the language - it is only spoken, not written. In the school, lessons are given in Azerbaijani, with English and Russian being taught as additional languages. But in the homes and playground Lahiji is the usual language.

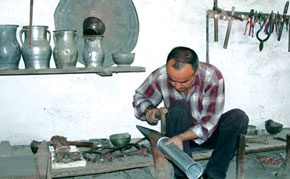

The town was originally a copper-mining hub, but that has died down. Unlike other Azerbaijani villages, agriculture is not an option here in this rocky barren landscape, hence Lahij´s development into a craft centre. Today´s Lahij is village of coppersmiths and carpet-makers, with the men working at the copper and the women at the carpets. There are some seven copper workshops, each employing one or two men, and there is one carpet factory which employs 30-35 women. Additionally, some women make carpets at home. These activities provide a good but seasonal income.

The carpet-weaving and copper and brass work (pots, samovars etc.) therefore sustain the village´s economy. Agriculture is minimal. Any animals kept are just to sustain the immediate family. Some people keep bees for honey.

But because visitors can only come in good weather, largely in the summer months, income is very seasonal. More Azerbaijani people than foreigners come in summer, with some Azerbaijanis choosing to rent a house for long periods. For this they pay perhaps 40 to 60 manats a day, depending on the house.

The village has a unique water supply system, which brings water down from the mountain in channels that flow through and under the streets of the village to emerge at strategically placed fountains.

Due to frequent earthquakes the village developed its own building techniques. Houses have layers of wood built into the walls to act as shock absorbers. The technique has proven results - the damage caused by quakes in places like Shemakha remains unseen in Lahij.

Houses in Lahij are built in this traditional style from local river stone. The narrow stone streets are immaculate, with not a stone out of place. Some of the buildings have plaques which give details of the age of the property. The local villagers are very proud of their village and they are very keen to maintain its unique identity. However the village is perhaps becoming a victim of its own success – apparently some Norwegians came and pronounced the Ismailly region, and Lahij in particular, as being the best places in Azerbaijan for "rest". Due to the heat in Baku in summer, mountain areas are sought out for their clean air and healthy environment. As a result a few rich Azerbaijani people have come and built modern style homes, for summer use. Local people want to defend their culture, including the local architecture, and would prefer to encourage guests to rent existing properties than to build new houses out of modern bricks.

Lahij villagers are unbelievably dependent on the treacherous simple dirt road for access. The road has been improved in recent years but it is still narrow and dangerous with a poor surface. There has been talk of laying a tarmac surface on the road, but it hasn’t happened yet. Any such improvements would need constant repair because of the nature of the terrain. More exciting is the plan to build a totally new access road from the opposite direction, from Quba and Xinaliq. Beneath the village there was a bridge across the river, built during Soviet times, which had been in preparation for a new route, maybe to copper mines. Within the last year this bridge has been replaced by another new bridge, which alas as yet still goes nowhere. However the people from Lahij are optimistic that the new road, once built, will bring more visitors, and thus income. Indeed, a round route from Baku linking Quba and Shemakha, and taking in the wonderful villages of Xinaliq and Lahij, can only be good for bringing tourism and money to the whole area. Lahij people have been leaving the village because living there is so difficult, and because employment opportunities are so seasonal and so limited. Youngsters leave to study or work in Baku, and travelling to Moscow for work is also a popular escape. The older people are keen to stay in Lahij. The school has been modernised and currently has some 330/340 pupils, age 6-18, and 45 teachers.

Heating continues in the same age old way - from wood cut from the forests higher in the mountains.

Lahij is where many Baku expats go as a sort of daring day out. It has got that "must see" reputation amongst the community. And why? Because it’s about as different from Baku as you can imagine, and you can get there and back in a day.

Arriving in Lahij is quite a surprise. The narrow cobbled streets bustle with activity, with horses, donkeys and residents going about their daily business, with older men sitting chatting, their flat black caps indicative of their traditions.

Every step you take in the centre of Lahij is accompanied by the knocking of hammers. You truly feel the spirit of medieval history. Horses and donkeys are more common than cars in the narrow stone streets. The views up and down the narrow passage ways end in glimpses of distant mountain summits.

The copper workshops are enticing. The copperwork is unusual and fantastic; you can see the men working at it, and you can buy it as a souvenir. Who can resist the warm glow of the shining copper, rich in intricate design, in the very workshop where it is made. Discuss the form, the shape, the function and the decoration. Afterwards, when safely back in Baku, just looking and holding the copper brings back the cosy memories of the sounds, the smell, and the homely atmosphere of the copper workshops. The designs are unique, often featuring the buta motif (known as the Paisley pattern in Scotland), which indicates links between here and India (and Scotland).

When you show your friends your wonderful purchases, and also describe how terrified you were on the road there, then they are persuaded that one day they too simply must experience the journey to Lahij.

Arriving in Lahij, don’t be too surprised to be greeted by Azerbaijani men wearing obviously expat clothing - BP gear which has served time in Alaska, for example. Expat people have taken this village to heart, and supply it with a regular and generous flow of goodies.

The young people from Lahij work in Baku. Some speak excellent English, and have become skilled in working with the expat population to promote their home village, and the needs of its population.

For its part, Lahij has become an excellent example of what the tourist wants to see. There is now a large café which will serve you. And you will be welcomed and shown around, and they will ask you for your business card, and you will hear about the needs of the village, and suggest that even if you are not going to come back to Lahij soon, you can send donations up via the young contacts in Baku. Now that they have your business card they can phone you and let you know when the next "run" will be. Ruslan (050 6120553) is particularly charming, and will try to ensure that you will get the most out of a visit to Lahij.

So apart from copperware and carpets, what can you expect to see?

You will be shown the history museum which is some 20 years old. Entry is free (maybe a small donation will be appreciated) and there is an English-speaking guide. Local people donate items to the museum which they think might be of interest. Exhibits are therefore varied, and there is absolutely no information available except whatever the guide can tell you. But local people are proud of their museum, and while it might need modernising, there is no doubt that it is a valuable asset.

You will also be told about the 13th century sewage system (yes, it’s over 800 years old) which can be walked in, being 1.2 m wide and 2m tall. No-one knows where the water goes.

And then there are horse trips to see Bur-Bulag, the ice spring, which is reputed to be water in winter and ice in summer, and to Qala Javanshir on Niyal mountain (one hour and three hours respectively).

Although not immediately apparent, there are a number of restaurants in Lahij. Try and ask for Shirvan Daghlari, Girdiman or Karim’s Restaurant. Some, like Karim’s, are simply known by the name of the owner.

If you want to stay longer, there is a hotel in Lahij; call Hidayat for details (050 6320732) who speaks Russian and Azerbaijani. Homestay and other accommodation is also available. For longer stays, do what the Azerbaijani people do and rent a house. Alternatively, if you don’t want to stay in Lahij itself, stop at the "red-roofed cabins" on the way up (summer only), or at the new but pricey Qaya hotel (all year round).

Feel the spirit of history and enjoy your stay.

Saribash – the forgotten village

Saribash is an idyllically situated small village in the north-west corner of Azerbaijan, way up the valley beyond Qax and Ilisu. Don’t even think about taking your 4x4 up there. Instead contact Senam on 050 673 52 34 and let him organise everything and drive you in a local jeep. It seems pricey and I must admit I was uncertain about whether to go on the trip. Afterwards I thought what good value it was.I made the journey in late summer with a family from the Qax area who have relatives in Saribash. I stayed in the comfortable Ulu Dag, a new resort in Ilisu. Allow a full day for your trip from Ilisu to Saribash. I went in September during a period of pleasantly warm sunny weather.I would never have attempted the journey in any other weather.

The first problem might be getting past the border guards. Saribash is in Azerbaijan but the border with Dagestan is nearby and the soldiers are not keen on letting foreigners past, though locals have no such problem.

Turn left in Ilisu, opposite the mosque, and you are on your way, heading up a steep sided river valley, through the river, and immediately you realise that this is no trip for immaculate, shiny city vehicles. Over stony tracks, going upstream where there is no road, back and forth over the stony river bed and eventually up to Saribash. Every time the river rises (when it rains in the mountains), the route changes. This can easily happen even in mid-summer, so don´t rely on a safe route even if the skies look blue. I was amazed at the terrain a Lada 4x4 could cope with. More than once I got out and walked or scrambled and watched as the car unbelievably made its way over or up another hurdle, at times in reverse gear. Quite how it got back unscathed I don´t know.

If you had to tackle this journey every time you wanted your groceries, would you live in Saribash? Probably not, and this is why the population has dropped from 150 families (1970s-80s) to 27 families. All we need, say the villagers, the only thing we would like to ask for, they say, is for the road to be improved.

In Soviet times this village had an electricity supply in advance of Ilisu and even Qax. This was because a small hydro-power scheme was built to serve the village. There was a large school, medical clinic, recreational club and a hamam for all the village.

Today the village comprises a number of old stone built cottages, most falling into disrepair yet remaining attractively ramshackle. The old shop is boarded up. The old bus, which used to make the journey up and down to Saribash twice a day, sits at its last stop, stationary, neglected and forlorn. The school is still used, but has not been modernized.

We were welcomed into a small courtyard of a private house where we sat at a table and were given tea and a delicious meal which included dolma and Saribash cheese - white, mountain sheep cheese with orange-flower petals through it. The Saribash people were keen for news and company and as the chatter continued amongst the older generation, I was taken on a walk with the youngsters round the village to see the sights.

The beauty of the location and the spirit of the people is a real attraction. Walking opportunities abound. Alongside the village there is a park. The locals call it Tala (clearing or glade) and it is an amazing natural amphitheatre with orchards, a football pitch and some statues. One is of a shepherd, Choban, signifying what the people do for a living. Another is of a soldier, and the third is of Lenin. During the Soviet Union, helicopters would land on the Tala.

We went for a further scramble up a river bed to show me the remains of the hydro-power station. Come here for some tempting, dare I say, canyoning/gorge-walking opportunities.

Today the people make most of their money from sheep, cows, and so on, but when the village had facilities then they could work in them, for example at the hospital, so there were more employment opportunities.

I watched a man walking with his horse up a narrow steep mountain path. In the horse’s saddlebag there was a single live sheep, being taken up to pasture. This is today’s face of farming in Saribash. An old narrow foot bridge, crossing a ravine and leading to a grazing terrace, is falling into disrepair. In Soviet times some 14,000 sheep were kept in the summer pastures above Saribash.

On the approach to Saribash, before making the final climb from the river bed, we had seen huge tree trunks and logs dropping down a ravine to the river bed where they were being loaded into the back of a small lorry.

Now, returning to the village after the tour to the power station, we meet the lorry inching its way up the hill, carrying the wood up for winter fuel. It stops and the men throw water over the radiator and engine to cool it. I am reminded of what we used to think in Scotland - cut your own wood and it will warm you twice.

A natural oak forest (Quercus macranthera) is diligently protected by the rural population and during the last 50 to 70 years no oak tree has been cut down in this forest at Saribash. (A 1996 source: http://www.fao.org/ag/AGP/agps/Pgrfa/pdf/azerbaij.pdf)

I listen to stories about Saribash, about what it used to be like.

"The first people in Saribash came from Turkey, and that’s why this village is called SariBash, Yellow Head. A lot of things they say here are said in the Turkish way.

"Tasan Mirzoyev was the man behind all the village improvements. He was my grandfather.

"A lot of families lived here, the road was better, the people there were happy, everybody had work and everything was working. I remember it in 1986-87. The bus came from Qax twice a day. We went by UAZ. My grandfather was there.

"Because my grandfather made a lot of things for this village, everyone was happy to see the family, and they were excited because we came from Baku. We stayed for three to four days. I was happy. Every day we went somewhere. We saw a lot of people, grandfather’s cousins, cousins sons, and so on.

"Now look, there are only a few families.

"Then there were a lot of families and children. We went to the Tala to play football. "At nights people were scared to go out, because it’s close to the mountains and the wild animals. At night they let all the dogs free, to roam the streets, to keep the village free from wolves.

"In those days you could feel life. You would see a lot of people in the streets, just walking, children playing. Now all these people have left Saribash and are in Qax or Baku.

"If the road is not improved then maybe in five or 10 years there will be nobody in this village. "I would not be happy if Saribash disappears, my mother was born there. Whenever I go to this village I feel at home.

"But I can’t live there. There is nothing, no hospital, no road.

"Pictures of my grandfather are in Qax, in the museum, with Heydar Aliyev, with Brezhnev, Podgorniy, when he was in Moscow. My grandfather had a lot of medals; the best was a medal of Hero of Soviet Socialist Labour. His collective farm had a Lenin medal. This was important and prestigious."

"On 15 March, 2006, the Qax local newspaper wrote in an obituary about Tasan Mirzoyev, ’We have lost one very famous person in our region. He was a very nice person, we have lost a good leader with good character, he died at the age of 80.’

"President Heydar Aliyev awarded him a President’s Pension. He had been awarded the Banner of the Red Worker, a lot of different medals and every year he attended the Red Square parades in Moscow."

I watched the film Our Village Hero, which was made in 1971. Indeed the village is full of life, full of people, and looks neat, tidy and prosperous. The work to make and maintain the road is also filmed.

But today, less than two years after the death of "the Hero", Saribash is a forgotten village. Unlike Xinaliq, with its new road and new school, and Lahij, with its international attention, Saribash is suffering from profound neglect and a total lack of investment. If you can make it to Saribash, the welcome you receive will be warm, appreciative and yet undemanding.

For me, today’s optimism, the happiness, is in the faces of the children. A seemingly idyllic lifestyle, riding horses bareback and playing football surrounded by the best mountain scenery. But the children are few compared with yesteryear.

And the future - who knows?

Saribash - I loved it there. I do hope I will be back…

Lahij

Lahij

Lahij

Lahij

Saribash

Saribash