– Mammad Amin Rasulzade, Chairman of the National Council of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic.

While women in different corners of the world were campaigning for equal rights, those in Azerbaijan were trying to pave their way towards education. One of the main features of the women’s movement here was that men started it. Popular printed publications of that time, the newspaper Ekinchi (founded by Hasan bey Zardabi) and the satirical magazine Molla Nasreddin (founded by Jalil Mammadguluzade) from time to time raised issues concerning women’s enlightenment. Such men were the leading representatives of the Azerbaijani intelligentsia and were firmly convinced that only a cultured and educated woman could give her children a good upbringing and provide them with better lives (see Ishiq, No.7 p.12, Behbud agha Shakhtakhtinsky). During the oil boom of those early years the struggle took place mainly in the new publications and charity communities being launched, most of them with the help of oil magnates. Among the most famous were surely Zeynalabdin Taghiyev and his wife Sona Taghiyeva.

According to Latifa Aliyeva in her Women in the Public and Political Life of Azerbaijan 1900-1920, the first society of Azerbaijani women was established in Tiflis [now Tbilisi – Ed.] in 1906 (many of the Caucasus intelligentsia were based there). The first Muslim women’s branch in Baku was opened by the Nijat (Salvation) society two years later. Among its founders was activist Khadija Alibeyova. Later she and her husband Mustafa Alibeyov launched a women’s newspaper, the first not only in Azerbaijan but in all the Near and Middle East…

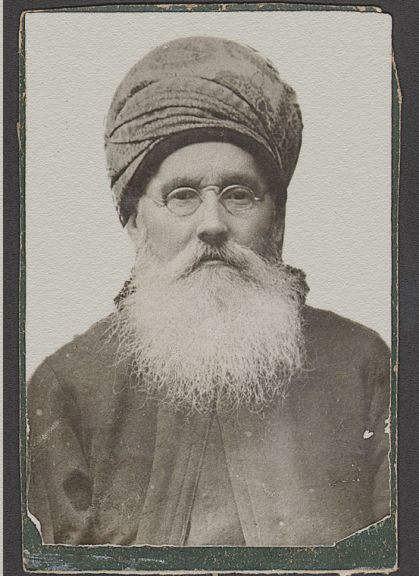

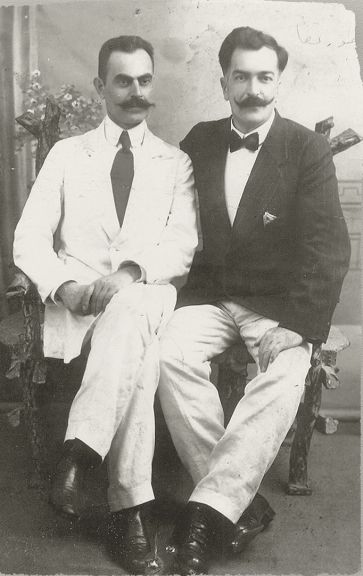

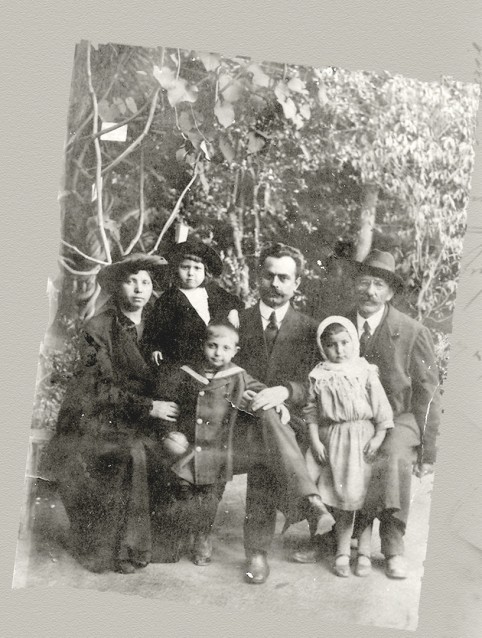

The Alibeyov family

Khadija was born in Tiflis, in 1884. Although her father was a cleric, he wanted to raise a well-educated and enlightened daughter. Thus, she graduated from the Russian Girls Gymnasium and then from the Olginskaya Institute of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Her social activity began after she married Mustafa Alibeyov, a well-known writer, lawyer and publisher. He was highly educated, knew several foreign languages and worked as a translator.

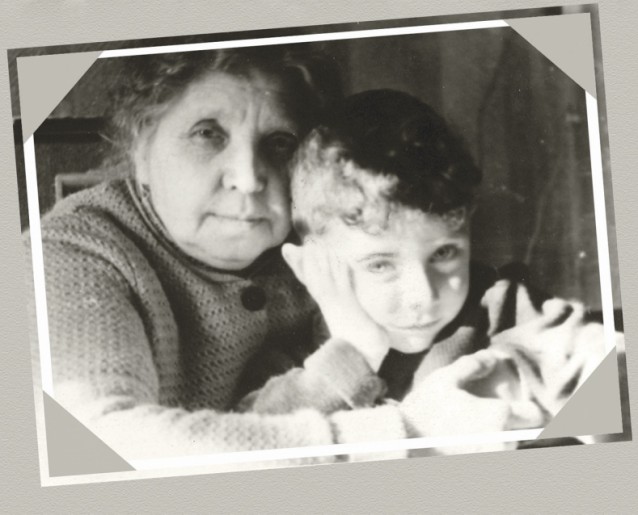

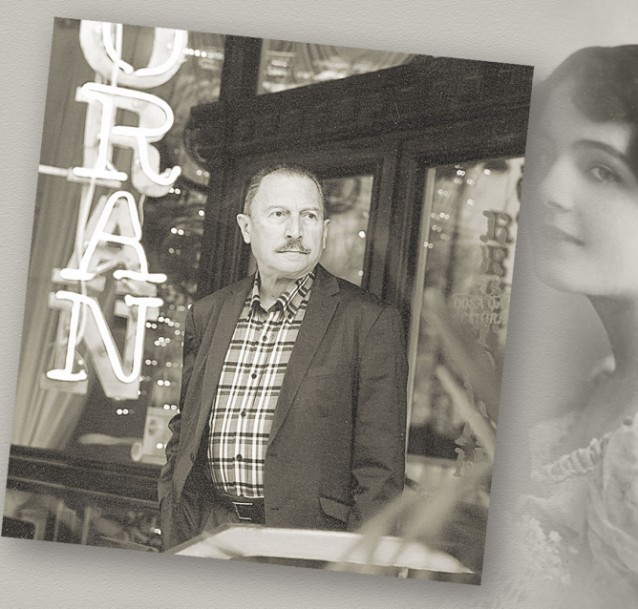

We were pleased to be able to meet Khadija’s grandson, Jamil Farajov, a well-known film producer, and he told us that Mustafa bey had first met his future father-in-law in Tiflis. Later, as required in traditional Azerbaijani families, he had asked for his daughter’s hand. Both Khadija and Mustafa were cultured, modern and intelligent… a great couple for that time. They eventually had five children, all of them going on to higher education.

The Alibeyovs lived and created within an environment of conservatism and prejudice. The tsarist regime opposed change. Ignorance and distorted ideology were the main tools employed to control the population. And most pitiful were the women. They were deprived of all rights and urged to cover their faces and hands. A woman’s life was to stay at home doing chores and having children.

Khadija, her husband and other progressive people believed that an illiterate woman with no rights would never be a good mother for her children. After the women’s section of Nijat opened, Khadija gained good experience of public work. New schools were opened and she went on to become the first woman editor in Azerbaijan.

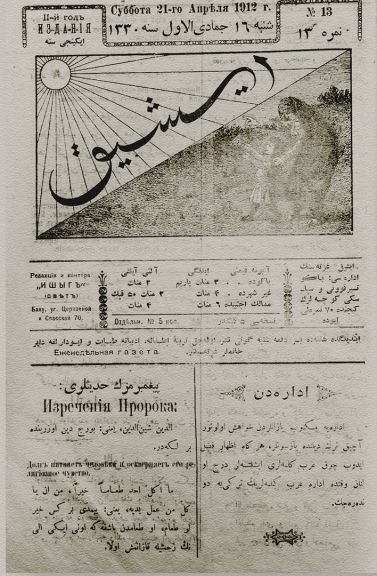

The struggle started on a cold winter day in 1911 when the first edition of Ishiq (Light) was issued. Khadija was the editor, Mustafa the publisher.

Getting close to the Light

On a warm February day 105 years later we visited the Institute of Manuscripts in Baku to check the collection of historical documents. Some editions of Ishiq are held there, others are in the State Archives. The staff willingly searched out old papers for us and suggested other sources. We came away very happy – nothing is as intriguing as reading the original. Ishiq was one of the first publications printed in the native language. But, we soon learned that old Azerbaijani is not as clear as the modern day language. Many words were very close to Arabic, and they were written in Arabic script (until 1929). We had to translate it and luckily we found Musa Akhundov, a researcher in Eastern studies. His skill as an interpreter became very helpful as our research continued.

The newspaper was published from 1911 to 1912 in 68 issues. Most of the journalists were women, and Ishiq’s male contributors were prominent enlighteners of the day: Muhammad Hadi, Shahtakhtinsky, Khadija’s husband – Mustafa Alibeyov - and others. It was distributed on the streets, later by subscription.

Issue No.2 of its first year (1911) is the earliest I found. The front page depicts a veiled woman with a child: one hand on his shoulder, another pointing to the sun (light). Further below are dates (this issue was dated 29 January 1911, a Sunday - it was actually released on Saturdays, even though the date given was a Sunday) then, lower down, prices; for subscriptions and ads. I was quite surprised to see that people were making money on adverts in those days. In this case, promotions included:

Subscription open for the only political, economical, literary, social newspaper for all Russia “in the Muslim world” dedicated to Russian Muslims.…

And even: an educated individual, knows German and French, speaks good Turkish, is looking for a position as teacher, governess or companion…. etc.

Reading Ishiq

Looking through the next page of the second issue I was under the impression I was reading some kind of instruction for men. Khadija, the writer of this article, referring to the Qur’an and clerical commentaries, tells men to be patient and to control their temper with their wives. Generally, the article is dedicated to marriage, its necessity and ways to maintain it.

Khadija, back row, third from left, with other society women. On the wall is a picture of Tsar Nicholas II which was scratched out in Soviet times

Khadija, back row, third from left, with other society women. On the wall is a picture of Tsar Nicholas II which was scratched out in Soviet times

The paper usually had between eight and 12 pages. Some issues included articles written in Russian (usually on the last page). An inscription in the middle of the front-page read: [Ishiq] is a women’s newspaper about children’s enlightenment and upbringing, medicine and housekeeping.

That was the main concept of Ishiq. The newspaper was never anti-religion or anti-men. Khadija and her husband were solely dedicated to education, broadening women’s horizons and achieving recognition for them as respectful, competent wives and mothers and members of society.

They trod very carefully. Khadija and the other writers often referred to the Qur’an and the Prophet’s commentaries that stressed the importance of education:

The quest for science is a commitment for every Muslim man and woman (a letter from Askhabad of 20 March 1911, Ishiq No.11)

The only forces they opposed were the false clerics and the stereotypes they created. Khadija, like other members of the intelligentsia, was aware of how those fanatics distorted religious principles and used them in ways beneficial to the authorities.

The more ignorant people are, the better and easier it is to manage them, was noted in one issue.

In his article, To the Moment (Ishiq, No.7, page 12), Shakhtakhtinsky wrote:

Women were far removed from education for a long time… We live with all these horrors (here he is referring to the many unhappy marriages and criminality) for the reason that demented, self-appointed moral authorities [the mullahs. Ed] have had too long and broad a grip on our fate and, finally, only school will provide us with the right means to remedy all these afflictions.

Another article, On the Issue of Women in Muslim Society (clearly written by one of the Alibeyovs, Ishiq No. 4, page 12), had:

They [the mullahs] knew firmly and clearly that, today, if some of the prayers are translated…. then people will probably soon be interested in the whole text of the Qur’an.... No, it’s just easier to say.… translation is a sin, it’s prohibited…. because the Qur’an includes many texts preaching ideas of freedom and brotherhood to all mankind...

The writer was displeased with women being urged to wear the chador, when Sharia law allows an uncovered face and hands. She (or he) concludes that Muslim women are allowed to engage in secular studies and that:

she is as free as a Muslim man, she is not a slave, but an equal member of the family and society.

Unique in its diversity

Teachers and students from the first Baku school for girls from time to time raised their voices on its pages. It was a newspaper with comprehensive coverage: medicine and health, family and housekeeping, children’s upbringing and education, religion, science and more. It shared letters, complaints, warnings, recipes, news, poems and even funny stories (Molla Nasreddin anecdotes). For example, there was once a letter written by a woman - a victim of brutal treatment - complaining about her husband, who had lost all his belongings, clothes and money to gambling. Another item informed readers of a newly released book - its price, 15 qepiks. And an excited note from Istanbul concerned a rich woman leaving five million roubles to the Ottoman authorities before her death. The editorial board applauded this deed, wishing for more from many similar sensible sisters in the Caucasus motherland.

Light in the Darkness, 2000

This is the title of the only book on Ishiq that I have found so far. One autumn Saturday I found time to go to the central library and was delighted to get it printed there. Reading Amalya Qasimova’s book, I discovered another side to Khadija. Along with the struggle for women’s rights she was also writing the following:

A woman’s duty keeps her at home. A woman should manage the chores around the house, raise children.… It is duty that confines her rather than anything else.

In another place:

Having two people in charge at home disrupts the order. While men are responsible for managing the house, women are responsible for obeying them (Issue No. 6).

She believed men to be stronger than women, and allowed that they should head the family. She also defended covering-up for women, believing it marked them out as chaste and honourable. Grandson Jamil Farajov stressed that she was writing within the framework of morality required by the conditions of the time. Interestingly, Qasimova’s book reveals that the celebrated Molla Nasreddin magazine and Ishiq periodically had “issues.”

You should also know that too much Light is not a good thing, it may dazzle the eyes, wrote Jalil Mammaguluzade, Molla Nasreddin’s editor.

Opposed to the view that educated women were losing their morals, Khadija insisted:

We make sure that educated and well-mannered women are absolutely innocent.

Feedback and financial problems

Once Ishiq was released, numerous congratulatory and admiring letters flooded in. Feedback came from Azerbaijani students in St. Petersburg, Odessa, Kiev, Tiflis, from ordinary people, poets, writers and of course the Molla Nasreddin editorial board. Naturally Khadija and her husband faced criticism as well, but this was a struggle and they were ready for it.

I had also read that there are copies of Ishiq in the Russian archives. Ragibe Mammadova, an advisor at the Azerbaijan State Archives, reported on a visit in 2013:

During a business trip to Moscow I visited the Russian State Library. Here I was interested in Ishiq, because some of its issues were distributed by subscription, delivery of the rest (200 copies) was free to other cities. So I was interested in how many copies were held in the library. I was given two sets: one was in a little casket with an image of the Russian imperial crown stitched on it in golden thread and addressed to the tsarina, Alexandra Fedorovna. These were issues 1 to 34 of Ishiq from 1911. The second set included issues 1 to 13 from 1912.

Khadija had asked permission to send them as a gift to the tsarina, wife of Nicholas II. Ishiq had financial problems - the clerics’ criticism was leading to loss of circulation and many writers had become wary of collaborating with the newspaper. Khadija was aware of the danger that it might be closed and was therefore doing her best to prevent this. But, finally, Ishiq could not survive any longer and after two years the first women’s newspaper in the Near and Middle East ceased publication.

Life without Light

From 1920-1946 the Alibeyov family lived in Sheki. Work did not stop: many of them benefited from courses and educational centres. A gynaecology department and medical college were opened. Khadija worked as a gynaecologist during this time, but 1937 was to be the most tragic of her life.

I learned the story from Jamil Farajov. Although very busy, he gave me old photos of his amazing grandmother, a film about her that he had contributed to and some newspaper cuttings. When I asked about his grandfather’s arrest, he confirmed what I had read:

At a discussion about the Soviet constitution, Mustafa bey argued for most of Azerbaijan’s oil to remain the property of its owners rather than of the state. He also urged the building of a railway station and a military fleet. When the meeting ended, a mysterious black car picked him up and never brought him back. Mustafa Alibeyov was arrested and exiled. Five years later he died far from his motherland, leaving behind only a beautiful garden in Sheki still known as “Mustafa bey’s Garden.” Later, one of his companions told Khadija how Mustafa bey had died in his arms, how he had suffered from an infection and how the companion had buried him apart from the others. Although he described the burial place, their son Anvar failed to find it.

Khadija moved back to Baku with her children. Life went on but another trial awaited. Her son Samsam was tragically killed in a fall from the fifth floor. As Jamil muellim recalls, this terrible accident was hidden from her but, longing for her son, Khadija could not live with her suspicions and died in 1961.

Khadija loved her grandson very much. Jamil Farajov was just 14 when she died and he saw her off by carrying the coffin. He remembers his grandmother as a very beautiful and wise woman, and says:

My mum was the first professor of economics in the East, she was head of the Department of Oil and Chemistry at the State Oil Academy. I spent a lot of time with my grandmother. She cooked well, I loved her khvorost - crunchy strips of dough with sugar on top.... She used to lay out cards playing solitaire and humming songs to herself. She wasn’t very talkative; she was thoughtful and quiet.

Fortunately, Jamil’s life has given him another Khadija: his daughter bears the name of her great grandmother. He says they are very similar; the younger Khadija has also found herself in medicine. She teaches genetics at the Medical University.

Legacy

Khadija was a very self-aware woman; she strove for people, strove for a better future. Ishiq shed the light of hope in people’s hearts. Although its flame did not burn for long, it certainly left behind a number of continuously glowing sparks. It registered a number of firsts: the first woman editor and first women journalists were born on its pages, the number of girls willing to get an education at the Baku school for girls increased notably and, importantly, the newspaper provided a focus, bringing together the local intelligentsia of the day.

It was part of a national women’s movement that ultimately led to the proclamation of women’s suffrage in Azerbaijan in 1918, the first in the East and preceding that in the USA and other western countries.

About the author: Narmin Mahmudova is a young writer with an interest in women’s issues.