When I meet young authors, there is one question I always think about, and that is, how do you know you are a writer? More often than not, the motivation is writing for the sake of writing and becoming a recognizable name in the literary world, rather than something essential to one’s expression. And in each conversation that transfers me to their world full of complexities and inner conflicts, I always hope to hear some hint of the latter.

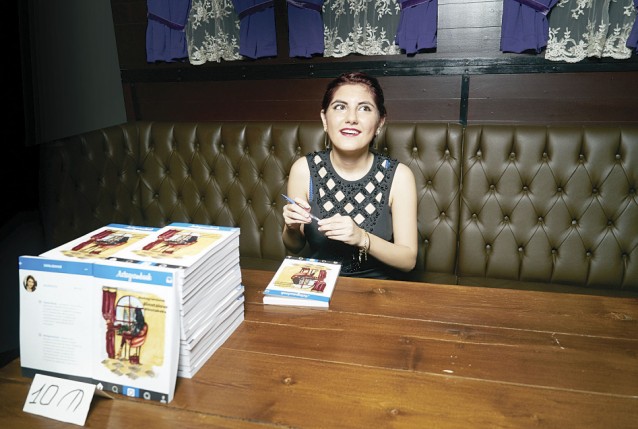

Clutching my coffee mug to warm my hands from the first bites of Baku’s winter, I try to guess what my guest writer is going to be like. Her unique name, Sayali, has been popping up on my social media feed ever since she published her debut novel, #Aztagrambook, which inevitably drew me to this young talent.

As expected, there is a story behind this unique Azerbaijani name, meaning “happy” or “lucky.” In some Azerbaijani families, there is a tradition to call children in honour of the elders in the family, and the Baharovs were not an exception. Sayali was named after her great-grandmother, and her sister Khaver, after her grandmother, both on the father’s side.

What’s interesting is that the initiative came from my mother herself, because she really liked the name. And although it now seems to be to her liking, Sayali didn’t always share the same opinion: When I was younger, I was always self-conscious about it; I wanted to be like everybody else, without such a complex name. But now I feel very comfortable with it.

As a child, Sayali was always withdrawn and quiet, which, by the way, she doesn’t consider negative because, as she puts it herself, I was simply engrossed in my endless inner world. From as early as 12, she somehow had a feeling that someday she would write. Like a poet in search of a muse, her personality and interests kept changing as she was trying to figure out her desires and what she wanted to do with her life.

Until a certain time, she preferred the company of her older sister Khaver and her friends to that of her classmates. But as she got older, her worldview started to change and she embraced new friendships and a new version of herself. School continued not to interest her much, and she still didn’t know what she wanted from life, but one thing that didn’t change was her desire to write. Foreign languages became an engrossing interest and then her professional outlet, as she currently teaches Italian.

The disinterest in school continued until 10th grade, when she realised she wanted to pursue a career in humanities:

It was probably the easiest decision I’ve ever made in my life. However, specifying the faculty (Journalism or Law) became a real dilemma.

My father didn’t want me to be a philologist, because it wouldn’t secure any prospects for me. But it was my decision to apply to MSU Baku campus (Moscow State University branch). I really liked that university and I ended up being admitted.

When I ask how she knew she wanted to write, she recalls her many diaries and school essays: It was my forte. I never specifically prepared for school essays, I just wrote them on the spot. It was always strange to me why people had to prep in advance. Whenever I decided to try and prepare, I ended up with too much material, and my teacher always teased me, saying: “The more you write, the more mistakes you make.”

Surely someone like her would have been an avid reader from early on, so I ask about her first favourite book. Picking one, as expected, becomes a challenge: I was reading everything I heard about, everything my father suggested. He also loved reading. I think I inherited my innate literacy from him. I was reading every book he ever talked about, every classic he ever spoke of.

I used to love reading at night with a flashlight. I remember my favourite was Agatha Christie and, actually, all kinds of detectives.

And of course, Ali and Nino… which is natural. It would be strange if I didn’t like it. I read it a couple of times, the very first time on the recommendation of my dad, when the novel was first introduced in 2004-2005. I was stunned when I read it. I felt so nostalgic, as if I had left this Baku; as if these heroes lived in one city and we lived in a parallel reality. I was about 10 and I really wanted to know more about this period, about these people. I’ve reread it many times, and again recently, before the film premiere. This book has indeed had a huge impact on me.

I remember, several years ago, talking to the Italian ambassador’s wife and she was just blown away by this book. And given that it has been translated into so many languages, so many of my friends from Italy, and even our compatriots, have raved about it. The surprising thing is that among my friends here, at the time, none had read the book, although some had heard about it.

In the philology faculty every semester students were given long lists of literature to read. I always had C’s in Literature, she says, I didn’t like compulsory reading. I wanted to write and to read only what I was interested in.

She started reading Azerbaijani literature from very early on, which must have been on her own initiative, since not all Azerbaijani authors are included in the school programme, not to mention the ones she really liked, who include, as she says:

Mostly writers of the 20th century, like Anar, Ismayil Shikhli, Aziza Jafarzadeh. Aziza, is not very well-known, I suppose. She specialized in Eastern studies, wrote historical novels. The most well-known novel by her is called 1501, about Shah Ismayil Khatai. The other one is about Seyid Azim Shirvani. Whenever I read Azerbaijani literature, I always felt the connection, and I loved it. It’s still like that for me.

Not surprisingly, it is Azerbaijani literature that has awoken the writer in her: I remember how I started writing my book. I was reading Elchin’s Mahmud and Maryam, well actually, prior to reading it my sister and I went to a film premiere. After seeing the film I decided I needed to read it.

And the moment she finished reading the book, she knew she was ready to write.

About the book

Sayali didn’t really have a well-defined idea when she began to write #Aztagrambook. What she started as a short story turned into a constant stream of consciousness. If it could be distilled to just a few lines, it is a book about young people and the pressure from their families. About how our life is defined by the hard limits created by our society, friends and parents, as she explains:

Our city is small, and everybody knows everyone, and everyone gossips. I tried to show all the things that I feel about this situation, but to say what exactly this book is about – I find it hard. When I was at school, there was one contingent, but when I entered university, the people also changed drastically. I saw the difference and how huge the gap between the two groups of people was, regardless of the fact that we are actually living in the same city. I wanted to describe our society, our youth.

But it turned out to be very hard to describe one particular layer of the population, because we are all very different, this is the very first thing I tell visiting guests. Baku can have many faces. And the people walking the streets of our city are not all the same. There are modern families and then there are very conservative families. And I know my book didn’t end up the way I intended it to, I couldn’t open up the characters the way I wanted to from the beginning. I had to sort of typify.

I always say it’s a satire on Azerbaijani society. When the type of people I unwittingly criticized, read this book, they find themselves there and they empathise with those characters, they don’t take it negatively. People that share my point of view - disagreeing with conservatism and patriarchal society - they see the satire and they laugh with me. Everybody sees this book differently. Probably because, as I said previously, there are so many different kinds of people living in this city that it’s impossible to create a typical portrait. Unless, of course, you’re talking about a taxi driver (she laughs).

Touching on such complex and sensitive societal issues is undoubtedly intimidating and, as Sayali was still in the process of writing, she would post parts of the book online to see the preliminary reactions. Along with the positive notes from her friends, she also received a fair amount of anonymous messages, which were criticisms and accusations that she was “just jealous” and “unfairly criticising” people.

Although I think I’ve successfully managed not to criticize anyone, it was quite intimidating, but I don’t regret writing it. If I hadn’t written this book, which touches on some serious issues, I wouldn’t have been able to move forward, I always say it was my first attempt at writing.

The title of the book was also among the things she had to ponder. Right before publication, she came up with #Aztagrambook: This was around the time hashtags started to become “a thing,” and I wanted to incorporate it to show how obsessed people had become with social media (Instagram).

Despite the popular belief that most women’s prose is autobiographical, Sayali disagrees and points out that she can’t directly identify herself in any of the characters: Maybe subconsciously I am the main character, however we have different biographies; maybe it’s my alter ego, a different side of me, but generally I can say that no, I tried to distance myself from the characters.

To me, the process of writing a book, from the inception of an idea to the final presentation, is quite complex. Especially for a self-publisher, who becomes responsible for the entire process, so I am a bit surprised that the only difficulty Sayali encountered was her own fear of reading the final version of the novel:

After it had been edited, I felt scared and awkward. Maybe it was the aftershocks from those anonymous messages kicking in. I was this serious girl who wrote a book about silly girls who became prisoners of their own stereotypes. I thought I had to write about more serious issues.

For the longest time she was putting off organizing the presentation, because of that fear. But, luckily, friends chimed in and helped greatly with the organization and everything went smoothly.

In general, the book was well received. Of course there were those who called it a perfect commercially beneficial project, because I left it unfinished. But I can take criticism pretty well, she says.

The most likely next project, as she feels almost obliged, is finishing the second book, the continuation of the first, since the narrative cuts abruptly. Her future plans are definitely promising, from processing her diaries and producing something out of them to writing on women’s issues:

Even though I realise that the gender issue has to do with both men and women, I’d like to put an emphasis on women and maybe even try non-fiction as a mode of expression.

Her range of interests is wide, including psychology, the theory of religion, mysticism, Sufism, esoterics. And the defining characteristic of all her varying interests – she wants to explore them in the context of Azerbaijani society:

I’m always attracted to Azerbaijan. And even all these problems and issues I’d like to explore within our society. Writing about all of them is undoubtedly interesting, but I know I’m not there yet. I’m not yet ready.

Authors often borrow stories that they’ve heard and give life to them on the pages of their novels. Sayali, as I am not surprised to find out, has a different take on this:

I don’t like describing real people or real events. It’s definitely interesting and I respect people who do that, but I prefer making stories up instead of using the ones I hear. I think it’s always better to build it like a puzzle, to come up with something new. People often think I use their stories in my writing, maybe I do unconsciously or maybe it just happens.

Her blog

It is no surprise either to hear that Sayali is a blogger too: My blog was my self-expression. I started it in 2012, I didn’t seriously pursue writing or publishing anything prior to that. At the beginning it was scary, I compare it to being naked in public, you’re showing everyone what’s in your head, in your soul, and sometimes you can feel ashamed for what’s in your head. By writing provocative articles, I wanted to shake up this society, to generate a public response.

I stepped away from it for a while, but now I want to revive it, but differently. I now tend to be softer, more peaceful in my writing, explaining my point of view and providing enough valid arguments for it. I don’t impose it on anyone. I used to have this stance: there is my opinion and then there’s the wrong opinion. Now I understand that all people are different, have different backgrounds, pasts and their own aims. You can’t impose anything, but sharing your point of view is essential.

I also want to make my blog more informative, so that people can access useful information on it; and to do projects with people, maybe the foreigners that live in Baku, or women in Baku who choose to be childfree (the childfree concept is still a novelty in predominantly family-oriented Azerbaijani society - Ed.).

As our interesting conversation comes to an end, I wonder whether our enigmatic author has a dream:

It’s a relative concept, but I really would like to be remembered in Azerbaijan, even if I leave one day. I want to contribute to something meaningful, to know that I could change something. But I don’t want to be too obsessed with this idea. Because, often, those people who brought grand ideas into this world, were very unhappy in their personal lives. Dale Carnegie who died in complete loneliness, for example. I may not become that famous, but I would certainly love to contribute to the bettering of our society. I think there is no harm in dreaming big.