3 roads into the mountains

Lake Goygol is often cited as the region’s top attraction and is reachable via a beautiful road wending its provincial way from the southeast of Ganja high into the Lesser Caucasus Mountains. In summer the towns of Goygol and Hajikend are popular with local Ganjarites escaping from the city’s sizzling temperatures, and in winter they turn into wintery wonderlands whose woods are dotted with chaikhanas, colourful lights and steaming samovars. Foreigners are still a rarity here. When I happened upon this route over a year ago, I was treated to the best in Azerbaijani hospitality at a local restaurant owned by some of Goygol’s last Assyrians, who once lived side by side with the town’s Swabian German settlers until Stalinist deportations began in the 1930s. I then continued my ascent in a tired Zhiguli with a jovial group of locals led by a colonel in the Ganja police force. At Hajikend, once a retreat for oil-boom millionaires, we stopped for tea at a small cabin in the woods heated by a rickety stove. A little higher the snow thickened and forced us to retreat before we were able to reach the spectacular views of Mt Kapaz.It was this mountain’s jagged peak that was responsible for creating the national park’s stunning scenery when a devastating earthquake in 1139 sent rocks hurtling from the mountain into the river Kurekchay, forming dams and lakes. Today Goygol and Maral Gol are the stuff of myth and legend and endless cultural inspiration, fittingly described by travel writer Mark Elliott in a recent Visions article as being as iconic to the Ganja region of Azerbaijan as the Maiden’s Tower is to Baku. For many years the Goygol National Park was mysteriously closed to the public, but fortunately for visitors to the region it suddenly reopened last year.

Shamkir to Gedabey

About a 30-minute drive west of Ganja another popular route into the mountains begins at Shamkir, a town also established by German settlers in the early 19th century (and originally called Annanfeld). Like Goygol it still has a Lutheran church and the central streets retain a pleasant central European feel. The road from here has similarly stunning views of alpine meadows, rugged canyons and hard-to-reach historical ruins all the way to Gedabey, a mining town whose copper deposits attracted the Siemens brothers at the end of the 19th century. Today the town is being mined for gold and is also renowned for growing Azerbaijan’s tastiest potatoes. The remains of a bridge built by the Siemens brothers in the village of Duzyurd to connect the copper mine with the smelting plant

The remains of a bridge built by the Siemens brothers in the village of Duzyurd to connect the copper mine with the smelting plant

Shortly before Gedabey is the village of Slavyanka, founded in 1844 by Russian “spirit wrestlers” (Doukhobors). In 1895 Slavyanka’s villagers were among the masses of Doukhobors from across the Yelizavetpol, Tiflis and Kars regions to burn their weapons in protest against mandatory military service in the Tsar’s army. Shortly after, many of them emigrated to Canada with the financial support of Russian writer Leo Tolstoy, who donated some of the proceeds from Resurrection and others of his works. Today, few Russian villagers remain in the original village but the rustic izba-style houses evoke their fascinating past. Since 2004, a local spring has been supplying water under the brand Slavyanka 1.

In between these two routes lies another alternative, whose unusual recent history is also still very much evident today.

New Ganja to Khosh Bulaq

This road snakes its way into the Lesser Caucasus Mountains from the western suburb of Ganja known as Yeni Ganja or “New Ganja,” and ends up in the neatly planned town of Khosh Bulaq. There, an enormous reservoir lies like a giant mirror reflecting the distant mountain peaks and clouds and locals picnic in the shade of a distant wood. The healing properties of the mountain air, natural springs and medicinal herbs make this a popular dacha spot for Ganjarites, for whom, finances permitting, acquiring a dacha is quite a simple process. The hardest part might be tracking down the local government-appointed roaming estate agent, who will point out the specially allocated plots (prices start from $5,000) on which to build one’s own mountain retreat.But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. The road begins in “New Ganja,” a blend of recently built apartment blocks, each with a mural depicting scenes from poems by Ganja’s favourite son Nizami Ganjavi, and opposite, the new Heydar Aliyev complex, which has a dramatic Arc de Triomphe-style entrance, long promenade and theme park called “Luna Park.” It was from here that we set off recently on our gradual ascent, first passing a livestock bazaar appearing on the last of the dusty suburban terrain, taking me back in my thoughts to a similar scene I witnessed in the ancient Silk Road city of Bukhara in Uzbekistan. Ganja too was a hub for Silk Road merchants during those years.

Very quickly this terrain changed from semi-desert to greener pastures, the air noticeably cooled and little kebab and tendir bread stalls emerged from time to time beside the road. On the return leg we would stop at one of those, and observe as a short, thickset woman sporting a traditionally colourful headscarf skilfully pasted the interior of the oven with innumerable tendir doughs. Needless to say our mouths were soon watering from the enticing buttery smell, to such an extent that immediately after leaving we wolfed down several delicious loaves.

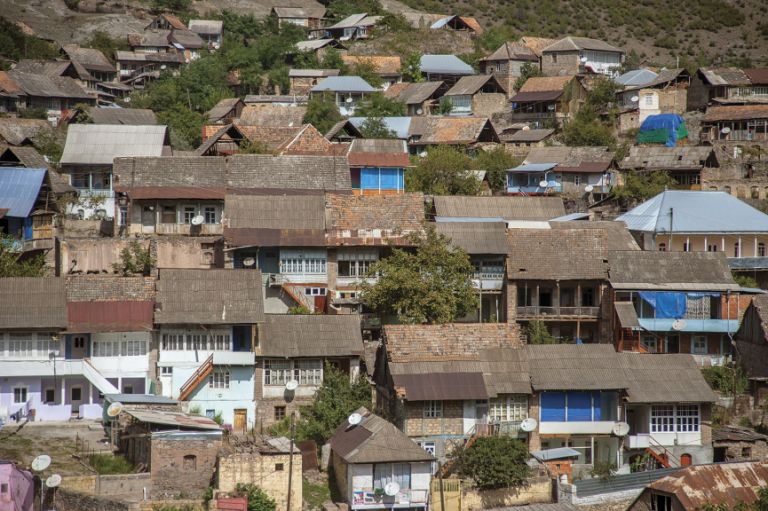

A little higher on the ascent we were charmed by rustic Bayan, a village largely populated by Armenians prior to the Karabakh conflict. I couldn’t help thinking how its old stone houses built compactly against the steep mountainside and timeless 19th century character were strangely reminiscent of French writer Alexandre Dumas’ impressions of arriving in Old Tbilisi:

Almost overhanging it [the River Kura – Ed.] on both sides of the chasm rose haphazard clusters of houses, tier after tier, wherever they could find a foothold, like a flock of birds perched among the rocks (from Adventures in the Caucasus by Alexandre Dumas – Ed).

It was not for the first time in Azerbaijan that a mountain village seemed to have existed untouched in its own little world. And it was from about here onwards that we began to see glimmers of what we had come to document: an old railway line, bridge and cable cars hanging motionless, suspended in mid-air, connected to the surrounding mountain tops unnervingly, like a giant spider web. They sat frozen in time, as though reminders of a lost world.

A lost world

Few tourists are likely to hear of Dashkesan (lit. “Stone Cutter”) but it wasn’t so long ago that this was the largest mining region in the Caucasus, rich in mineral resources such as iron ore, cobalt, white marble, limestone, quartz, bentonite clay and alunites, which led to the region’s nickname as “the Urals of Azerbaijan.” The region’s iron ore deposit was used for centuries, while cobalt attracted the attention of prospectors in the 19th century (who included the Siemens brothers) and iron was smelted to produce weapons and farming tools up until the Russian Revolution in 1917.In the early 20th century the area was heavily prospected, but the two world wars prevented any production on an industrial scale. This finally began in 1954, when the Azerbaijan Mining and Refining Facility was built, and went on to serve the aluminium factories in Ganja and Sumgayit and the Rustavi metal works in Georgia. A 1991 booklet stated that the region extracted 2,150,000 tonnes of iron ore each year.

During those years a railway was used to transport the ore from the mines and then on to the metal works in nearby Rustavi, until this was closed after the fall of the USSR. Small quantities were then sent to Turkey and other countries but it seems that this was the point when Dashkesan went into decline. The infrastructure to support this - the railway, factories and the town of Dashkesan sitting atop a mountain peak - were built by German POWs in the immediate post-war years. When the Germans began to leave in the late 1940s, Soviet prisoners were drafted in. Many of them mastered specific labour skills and decided to stay having later been granted amnesty. According to one former resident, the town began to grow in the 1960s as young people migrated from surrounding villages as well as graduate specialists, mainly from the Azerbaijan Oil and Chemistry Institute, Azerbaijan State University and Moscow State Mining University. In such a way Dashkesan acquired a uniquely mixed population geared towards exploiting the region’s rich geology.

When we visited it was clear that the region’s glory days were long gone. A couple of refining factories sat poignantly like enormous abandoned spaceships at different points along the road. The town itself presented an equally sad scene. Roads were unkempt and the uninspiring bazaar seemed the centre of activity. Grizzled local men occupied themselves by playing nard in the teahouse nearby and the tiny village museum was hard to find and failed to really evoke the former scale of industry here. Rather fittingly, we were handed a small information brochure printed in 1991.

However, pockets of production are still taking place. Just beyond the town, a few lone diggers toiled sluggishly away beneath a marble quarry dug into the mountain like an ancient amphitheatre. Back at the entrance to Dashkesan, an impressive statue of a miner wielding a pickaxe stands defiantly, as though waiting for the region’s industry to rise again. In tune with this, a presidential decree was passed in 2013 to establish the Azerbaijan Steel Production Complex (ASPC) to help resurrect the country’s metallurgical industry. The Dashkesan Ore Dressing Plant, operating under the ASPC, is also subject to a development plan from 2015-18. In the meantime, however, the region is worth visiting for the scenery alone, so we hope you enjoy the accompanying images.