or How to try and hijack a three billion dollar oil deal on the back of a 650 CC Soviet-era motorcycle

Pages 12-17

Pages 12-17

by Thomas Goltz

It all started at an April 2000 conference devoted to the threat of Islamic fundamentalism to the newly independent states of post- Soviet Central Asia. After the final meal, a small number of participants went to the Adams Morgan townhouse of Johns Hopkins’ Professor Frederick Starr to have a chat.

"You know how we do it, Tommy?" said Starr. "We deliver it via Ural."

I had no idea what he was talking about, and told him so.

"Dr Fritz," I said, using my pet name for Fred. "What are you talking about?"

"Baku-Ceyhan, of course," chortled Starr. "We’re gonna deliver the first barrel of Caspian crude down the pipeline route, and in the side car of Soviet motorcycles! Haha!"

Everybody else in the room laughed along, maybe imagining Doctor Fritz, goggles splattered with insects and a dirty scarf trailing behind him in the breeze, lurching over a hill somewhere in western Georgia - and I do not mean Atlanta. Everybody, that is, but me.

Because I was having an epiphany.

***

Perhaps it depends where your erogenous zones are.

One of mine is Caspian oil.

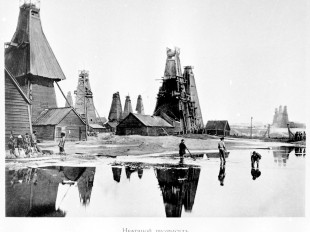

I have been writing and speaking about the subject for years, since 1991 in fact, when I first stumbled into the then Soviet Socialist Republic of Azerbaijan, back when there still was a USSR and people who lived there were still lining up for everything from bread to plastic buckets and certainly petroleum, even though the place had been producing crude since back to the days of the Nobel Brothers and the Rothschilds.

Stalin got his start as a Bolshevik organiser among the disgruntled oilfield labourers outside Baku. Had Hitler managed to seize control (there is a famous piece of film footage of his tucking into a piece of his birthday cake, designed as a map of the USSR, with his chunk defined by ’Baku’ in the frosting) World War II might have ended a little differently.

Happily, the allies - then the United States, USSR, United Kingdom and a batch of others - prevailed, setting the stage for the general nastiness of the Cold War, when the anti-Hitlerian allies became enemies and nearly scorched the Earth out of general, anti-other principle. And, while the USA was going from Kennedy to Johnson to Nixon to Ford to Carter and then Reagan, things were also going from bad to worse in the bad old USSR. After Khrushchev came the era of stagnation under Leonid Brezhnev, followed by Spy-master Yurii Andropov and then (skipping a few beats here) Mikhail Gorbachev. Along the way, everyone assumed that Caspian Oil - and thus Baku and Azerbaijan - had lost all relevance in the world oil market.

Dried up.

The only thing left were the vast fields of dysfunctional oil equipment like the rusting steel donkeys, bobbing up and down over an on-shore sea of rusting, leaking pipes in landscapes straight out of hell, desperately trying to leach the last few pints of residual hydrocarbon sweat from reluctant, subterranean reservoirs.

No, it wasn’t pretty. It was an ecological, sociological and economic nightmare.

Then came 19 August 1991, and the abortive putsch against Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev and the collapse of the Soviet Union and the independence of Azerbaijan and the other 14 republics that made up the USSR.

Communism, with all (or most) of its variants, was declared dead.

And with that historic funeral/event, the first soundings of western oilmen, interested in checking their data against that of the late, great Soviet Oil Industry. First came the wild cats and con-men, bribing their way into concessions they could not possibly drill or maintain; they were followed by Amoco, Conoco, Unocal, Statoil and then the big-boy on the block, BP. They scorned the on-shore stuff, and focused on the Caspian Sea bed. A dry hole here, another disappointment there, and then, with a gush and a rush, one, two and then three and four wet holes, and the Caspian was back on the international oil map, and the capital of the former sleepy, run-down (former) Soviet Socialist Republic of Azerbaijan became, once again, known as ’Booming Baku.’

But from the start, the problem was how to get the Ice Cream out.

(Ice Cream, I was to learn from my new oil industry pals, I.C. Cummingspoetic followers all, is the term used when referring to crude oil deliveries of the shark-driven spot-market variety, but of that, more anon.)

You could refurbish as many train tankers as you wanted, but the bribes involved in lifting, shipping, storage and loading crude down the fabulously corrupt Baku-Batumi railway were such as to make long-term business untenable. I once did a little off-the cuff research on the subject and determined that something in the order of 25% of all the Ice Cream so shipped went missing somewhere along the line.

No, for long-term viability, the only answer was a pipeline - and not another one of those over-the-ground, second-rate steel jobbies favored by Soviet-era planners, that spanned road and field like so many bizarre pieces of Lego. Local folks along existing lines had a habit of enhancing their (non) incomes by drilling into the steel tubes and siphoning off as much crude as they cared to crack and convert into bad gasoline in homemade refineries. No, if the growing millions and then billions invested in off-shore platform and over-paid expatriate engineer were ever to be recouped by actual production, there had to be a secure means of getting the black gold to international market - in other worlds, a gleaming new (actually, properly cement-coated and definitely underground) 44-inch, state-of-the-art delivery system leading from the bottom of the Caspian to the Mediterranean, and one that avoided the Black Sea for ecological reasons and Russia, Armenia and Iran for political ones.

There was only one such route: a tortuous, 1,700 kilometre (1,000 mile) meander over mountain and meadow, desert and ditch, river and ravine, starting in Baku, Azerbaijan and ending in Ceyhan, Turkey - and thus known to the petro-chemical world as "Baku-Ceyhan," although it would eventually be known as the "BTC," as in Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan, with the inclusion of the capital city of Georgia into the name-equation, because said pipeline would need to transit the former- Soviet republic of Stalin’s birth to get between the drill-hole riches of the Caspian Sea and the export terminals of the Mediterranean.

A mouthful, I know.

But so was the BTC.

On paper, it was and is the second longest pipeline in the world.

As engineering concept, it was (and is) a true challenge - a throbbing shaft of steel traversing below sealevel desert and swamp, then 12,000 foot mountain passes and multiple earthquake zones. Politically, however, the BTC project was and is nonpareil in its audacity: the essence was that the pipeline was to thread the needle between inimical Russia and Iran, wiggling its way through various small intensity war zones before confronting international opposition in the guise of Non Governmental Organisations such as Friends of the Earth and Greenpeace.

Even before the BTC was properly commissioned, I loved it. I loved it in an irrational way that had nothing to do with its really ever delivering a drop of crude into my old, gas-guzzling Ford truck in Montana.

I loved it because from the first speculative utterances about the Baku- Ceyhan line, it attracted more enemies than investors. ’Pipeline to Nowhere’ was a familiar slur.

I loved it for the money it made me as a journalist, as the cheques came in from various publications interested in every burp and fart of the on-going negotiations, of the reports I got to write every time it looked like the project was doomed to every interview I set up for television teams with nay-sayers and die-hard believers.

I loved it for the cach? my growing knowledge of the issues brought me at international fora devoted to the subject of energy; I loved it for the cynicism mixed with idealism it brought out in me, for the level of real-world intrigue it delivered...

And finally, I loved it because it brought together, in a weird and wonderfully and wacky way, three countries I loved dearly - Turkey, Georgia and Azerbaijan - in which I have spent the last two decades of my adult life as a journalist-observer of elections and wars and coups, as a political scientist analysing the same with historical data and insight excluded from mere ’media’ reportage, and - finally - as a devoted fellow human being who embraces the macro and micro concerns of the people of those three countries, because, quite simply, I have lived with the Turks, Georgians and Azerbaijanis in periods of their extreme need, meaning war, social upheaval and personal disaster and delight.

How could I not love the BTC?

Especially if the method of approach happens to be literally driving down the BTC route aboard an IMZ, better known as an Ural, or nostalgic, three-wheel, World War II era motorcycle with a dozen other madmen and your own private circus...

And not just once.

Starting in the year 2000, we made the two-week trip down the BTC three times.

The first year was to deliver the first symbolic barrel of Azerbaijani crude; the second was to deliver the first 1000 CCs of Azerbaijani natural gas; the last was to deliver symbolic chunks of BTC pipe.

In the guise of the Oil Odyssey Organiser, or ’Triple Zero,’ a.k.a. ’TripZip,’ I became the head of a hydrocarbon convoy of a dozen three wheeler motorcycles. Other participants included my brother Vince (a life-long motorcyclist, who, in addition to dealing with the mechanics added a fraternal dynamic to the story), senior oil company executives breaking their assumed mold (’Dr’ Ewen Patterson, formerly of BP, chief among them), but not excluding other oil-field renegades. And did I mention the fact that Paul Wolfowitz of New American Century-fame (YES!) contacted us to see if he could tag along for the ride before a certain George W was elected (or selected) president of the US of A?

We are talking weird...

We are also talking real.

Real, because the Oil Odyssey was not just a bunch of wealthy white men on motorcycles, careening through obscure town and village on adrenaline rush.

For starters, the pace was slow due to the tendency of our World War II era side-car bikes to break down in the most undesirable of places. Happily, we had our heroes - local mechanics, such as Sasha and Vagif, who had both been champion bike riders during Soviet times, but had been reduced before their association with the Oil Odyssey to being welders making a mere $50 a month. The Oil Odyssey changed their lives.

Making the story even more complex is the extraordinary performance presence of the Oil Odyssey in-house entertainment ensemble - a six dancer/three musician/star singer group featuring the 300-pound Azerbaijan national artist known as Bilal...The theatre team performed at every camp-site - in cities and towns or outside the same in the deserts, forests and mountains of the BTC route, and their energy suffused the entire adventure.

What?

A traditional song & dance team rolling down a 1,000 mile proposed pipeline route in the heat, rain and snow in this post 9/11 age of suspicion of everything Muslim and Middle Eastern, and all for fun?

Well, yes...

***

What I had to do first was find out just where, exactly, the pipeline was supposed to run. Way back in the ancient historical year of 2000, this was easier said than done, as the schemata available about the BTC route consisted of a generic red line stretching from Baku to Ceyhan across Georgia, with no reference to roads. If I was going to be serious about taking up Fred Starr’s challenge, I had to come up with a map. The obvious place to find one was at Daniel Yergin’s (The Prize, et al) annual Cambridge Energy Research Associates ’Tale of Three Seas’ oil and gas conference in Istanbul. The conference was packed with oil and gas heavies, ranging from the Grand Old Man of Caspian oil and the mastermind behind the so-called Deal of the Century, Terry Adams, to the regional business developer from Conoco, a shark-faced guy named David Huber and the head of the AES multinational electrical mission to Tbilisi, a lanky Englishman by the name of Mike Scholey. All laughed and cackled when I told them of my ride-thepipeline scheme, and even wished me well. None of them, however, could lead me any closer to the real BTC line than the generic red line from Baku to Ceyhan.

Then fate entered the lists. Arriving late to the main lunch featuring a keynote speaker talking about how Noah’s flood was really a wall of water rolling up the Bosphorus from the Aegean to the Black Sea (then just a lake), I found myself sitting next to a man who recognised me from a dinner with his wife a decade before. I explained my problem, and he told me to give him a call at his office, as he had something to show me. I did so, and he introduced me in turn to a colleague who had participated in an aerial survey of a prospective BTC route for a best nameless Oil Giant. Perched in an office on the upper Bosphorus, my newfound friend rolled out a NATO aviation map with the entire Baku-Ceyhan line detailed to exact longitude and latitude thanks to GPS, or Global Positioning System coordinates.

"Why are you showing me this?" I asked. "Isn’t it confidential?"

"It is supposed to be top-top secret," said the engineer. "But the bastards treated me like a tea-boy. We Turks have got our pride. So I made a copy, and decided to show you when I heard about your insane motorcycle scheme."

Equipped with the map and essential security information, I headed east, overland, walking (driving, really) the proposed pipeline route in reverse, bound for Baku and the annual June Oil Expo, which coincided with my arrival. In addition to schmoozing with the oilies in hopes of getting some corporate sponsorship for my venture down the BTC, I also had to solve a minor technical detail: locating some motorcycles to ride. Aside from some rural models working farmland like small trucks, traffic police drove the only Ural sidecar bikes I had ever seen in Azerbaijan.

With one exception: an export model painted a scruffy red, always parked in front of the BP/Amoco headquarters at Villa Petrolea. Friends told me it belonged to the manager for human resources and administrative affairs, a Scot named Ewen Patterson. I had never met the man, but he had been described as a gentleman of the corporate persuasion, who wore wire-rim glasses and sported a thick Scots accent when he spoke at all. In other words, about a zillion miles away from my....uhh...effervescent style. Once again, I seemed to have run into a dead end. Then one night, standing at a poolside Oil Expo reception and reaching for some more caviar and vodka, I sensed someone at my elbow, and turned to find a dapper, tight-lipped gentleman with a look of what appeared to be Presbyterian disapproval.

"My name is Patterson," said the stranger. "And I hear you want to talk about Urals."

Almost in a whisper, he informed me that he had heard about a warehouse on the edge of town that contained some eight motorcycles.

"They appear to have fallen off a truck in exchange for a debt," he explained with a twinkle in his eye. "I should be able to pick them up cheap - and I mean cheap."

"What does cheap mean?"

It is as if we are discussing a drug deal.

"I’ll buy the lot and you pay me back later," he said.

"Why?" I asked in amazement.

"Let us just say that I prefer fiddling with alternators to sitting behind my desk," he said with an impish smile.

I had just acquired the bikes!

But now I had new concerns, and of a rather compelling nature. Specifically, while I had managed to convince a bunch of oil field wild cats and weird guys that I was, in fact, an International Motorcyclist Extraordinaire, there remained one horrible truth I was still not quite yet willing to share with anyone.

Prior to organizing the BTC extravaganza, I had never been on a motorcycle in my life.

Pages 12-17

Pages 12-17by Thomas Goltz

It all started at an April 2000 conference devoted to the threat of Islamic fundamentalism to the newly independent states of post- Soviet Central Asia. After the final meal, a small number of participants went to the Adams Morgan townhouse of Johns Hopkins’ Professor Frederick Starr to have a chat.

"You know how we do it, Tommy?" said Starr. "We deliver it via Ural."

I had no idea what he was talking about, and told him so.

"Dr Fritz," I said, using my pet name for Fred. "What are you talking about?"

"Baku-Ceyhan, of course," chortled Starr. "We’re gonna deliver the first barrel of Caspian crude down the pipeline route, and in the side car of Soviet motorcycles! Haha!"

Everybody else in the room laughed along, maybe imagining Doctor Fritz, goggles splattered with insects and a dirty scarf trailing behind him in the breeze, lurching over a hill somewhere in western Georgia - and I do not mean Atlanta. Everybody, that is, but me.

Because I was having an epiphany.

***

Perhaps it depends where your erogenous zones are.

One of mine is Caspian oil.

I have been writing and speaking about the subject for years, since 1991 in fact, when I first stumbled into the then Soviet Socialist Republic of Azerbaijan, back when there still was a USSR and people who lived there were still lining up for everything from bread to plastic buckets and certainly petroleum, even though the place had been producing crude since back to the days of the Nobel Brothers and the Rothschilds.

Stalin got his start as a Bolshevik organiser among the disgruntled oilfield labourers outside Baku. Had Hitler managed to seize control (there is a famous piece of film footage of his tucking into a piece of his birthday cake, designed as a map of the USSR, with his chunk defined by ’Baku’ in the frosting) World War II might have ended a little differently.

Happily, the allies - then the United States, USSR, United Kingdom and a batch of others - prevailed, setting the stage for the general nastiness of the Cold War, when the anti-Hitlerian allies became enemies and nearly scorched the Earth out of general, anti-other principle. And, while the USA was going from Kennedy to Johnson to Nixon to Ford to Carter and then Reagan, things were also going from bad to worse in the bad old USSR. After Khrushchev came the era of stagnation under Leonid Brezhnev, followed by Spy-master Yurii Andropov and then (skipping a few beats here) Mikhail Gorbachev. Along the way, everyone assumed that Caspian Oil - and thus Baku and Azerbaijan - had lost all relevance in the world oil market.

Dried up.

The only thing left were the vast fields of dysfunctional oil equipment like the rusting steel donkeys, bobbing up and down over an on-shore sea of rusting, leaking pipes in landscapes straight out of hell, desperately trying to leach the last few pints of residual hydrocarbon sweat from reluctant, subterranean reservoirs.

No, it wasn’t pretty. It was an ecological, sociological and economic nightmare.

Then came 19 August 1991, and the abortive putsch against Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev and the collapse of the Soviet Union and the independence of Azerbaijan and the other 14 republics that made up the USSR.

Communism, with all (or most) of its variants, was declared dead.

And with that historic funeral/event, the first soundings of western oilmen, interested in checking their data against that of the late, great Soviet Oil Industry. First came the wild cats and con-men, bribing their way into concessions they could not possibly drill or maintain; they were followed by Amoco, Conoco, Unocal, Statoil and then the big-boy on the block, BP. They scorned the on-shore stuff, and focused on the Caspian Sea bed. A dry hole here, another disappointment there, and then, with a gush and a rush, one, two and then three and four wet holes, and the Caspian was back on the international oil map, and the capital of the former sleepy, run-down (former) Soviet Socialist Republic of Azerbaijan became, once again, known as ’Booming Baku.’

But from the start, the problem was how to get the Ice Cream out.

(Ice Cream, I was to learn from my new oil industry pals, I.C. Cummingspoetic followers all, is the term used when referring to crude oil deliveries of the shark-driven spot-market variety, but of that, more anon.)

You could refurbish as many train tankers as you wanted, but the bribes involved in lifting, shipping, storage and loading crude down the fabulously corrupt Baku-Batumi railway were such as to make long-term business untenable. I once did a little off-the cuff research on the subject and determined that something in the order of 25% of all the Ice Cream so shipped went missing somewhere along the line.

No, for long-term viability, the only answer was a pipeline - and not another one of those over-the-ground, second-rate steel jobbies favored by Soviet-era planners, that spanned road and field like so many bizarre pieces of Lego. Local folks along existing lines had a habit of enhancing their (non) incomes by drilling into the steel tubes and siphoning off as much crude as they cared to crack and convert into bad gasoline in homemade refineries. No, if the growing millions and then billions invested in off-shore platform and over-paid expatriate engineer were ever to be recouped by actual production, there had to be a secure means of getting the black gold to international market - in other worlds, a gleaming new (actually, properly cement-coated and definitely underground) 44-inch, state-of-the-art delivery system leading from the bottom of the Caspian to the Mediterranean, and one that avoided the Black Sea for ecological reasons and Russia, Armenia and Iran for political ones.

There was only one such route: a tortuous, 1,700 kilometre (1,000 mile) meander over mountain and meadow, desert and ditch, river and ravine, starting in Baku, Azerbaijan and ending in Ceyhan, Turkey - and thus known to the petro-chemical world as "Baku-Ceyhan," although it would eventually be known as the "BTC," as in Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan, with the inclusion of the capital city of Georgia into the name-equation, because said pipeline would need to transit the former- Soviet republic of Stalin’s birth to get between the drill-hole riches of the Caspian Sea and the export terminals of the Mediterranean.

A mouthful, I know.

But so was the BTC.

On paper, it was and is the second longest pipeline in the world.

As engineering concept, it was (and is) a true challenge - a throbbing shaft of steel traversing below sealevel desert and swamp, then 12,000 foot mountain passes and multiple earthquake zones. Politically, however, the BTC project was and is nonpareil in its audacity: the essence was that the pipeline was to thread the needle between inimical Russia and Iran, wiggling its way through various small intensity war zones before confronting international opposition in the guise of Non Governmental Organisations such as Friends of the Earth and Greenpeace.

Even before the BTC was properly commissioned, I loved it. I loved it in an irrational way that had nothing to do with its really ever delivering a drop of crude into my old, gas-guzzling Ford truck in Montana.

I loved it because from the first speculative utterances about the Baku- Ceyhan line, it attracted more enemies than investors. ’Pipeline to Nowhere’ was a familiar slur.

I loved it for the money it made me as a journalist, as the cheques came in from various publications interested in every burp and fart of the on-going negotiations, of the reports I got to write every time it looked like the project was doomed to every interview I set up for television teams with nay-sayers and die-hard believers.

I loved it for the cach? my growing knowledge of the issues brought me at international fora devoted to the subject of energy; I loved it for the cynicism mixed with idealism it brought out in me, for the level of real-world intrigue it delivered...

And finally, I loved it because it brought together, in a weird and wonderfully and wacky way, three countries I loved dearly - Turkey, Georgia and Azerbaijan - in which I have spent the last two decades of my adult life as a journalist-observer of elections and wars and coups, as a political scientist analysing the same with historical data and insight excluded from mere ’media’ reportage, and - finally - as a devoted fellow human being who embraces the macro and micro concerns of the people of those three countries, because, quite simply, I have lived with the Turks, Georgians and Azerbaijanis in periods of their extreme need, meaning war, social upheaval and personal disaster and delight.

How could I not love the BTC?

Especially if the method of approach happens to be literally driving down the BTC route aboard an IMZ, better known as an Ural, or nostalgic, three-wheel, World War II era motorcycle with a dozen other madmen and your own private circus...

And not just once.

Starting in the year 2000, we made the two-week trip down the BTC three times.

The first year was to deliver the first symbolic barrel of Azerbaijani crude; the second was to deliver the first 1000 CCs of Azerbaijani natural gas; the last was to deliver symbolic chunks of BTC pipe.

In the guise of the Oil Odyssey Organiser, or ’Triple Zero,’ a.k.a. ’TripZip,’ I became the head of a hydrocarbon convoy of a dozen three wheeler motorcycles. Other participants included my brother Vince (a life-long motorcyclist, who, in addition to dealing with the mechanics added a fraternal dynamic to the story), senior oil company executives breaking their assumed mold (’Dr’ Ewen Patterson, formerly of BP, chief among them), but not excluding other oil-field renegades. And did I mention the fact that Paul Wolfowitz of New American Century-fame (YES!) contacted us to see if he could tag along for the ride before a certain George W was elected (or selected) president of the US of A?

We are talking weird...

We are also talking real.

Real, because the Oil Odyssey was not just a bunch of wealthy white men on motorcycles, careening through obscure town and village on adrenaline rush.

For starters, the pace was slow due to the tendency of our World War II era side-car bikes to break down in the most undesirable of places. Happily, we had our heroes - local mechanics, such as Sasha and Vagif, who had both been champion bike riders during Soviet times, but had been reduced before their association with the Oil Odyssey to being welders making a mere $50 a month. The Oil Odyssey changed their lives.

Making the story even more complex is the extraordinary performance presence of the Oil Odyssey in-house entertainment ensemble - a six dancer/three musician/star singer group featuring the 300-pound Azerbaijan national artist known as Bilal...The theatre team performed at every camp-site - in cities and towns or outside the same in the deserts, forests and mountains of the BTC route, and their energy suffused the entire adventure.

What?

A traditional song & dance team rolling down a 1,000 mile proposed pipeline route in the heat, rain and snow in this post 9/11 age of suspicion of everything Muslim and Middle Eastern, and all for fun?

Well, yes...

***

What I had to do first was find out just where, exactly, the pipeline was supposed to run. Way back in the ancient historical year of 2000, this was easier said than done, as the schemata available about the BTC route consisted of a generic red line stretching from Baku to Ceyhan across Georgia, with no reference to roads. If I was going to be serious about taking up Fred Starr’s challenge, I had to come up with a map. The obvious place to find one was at Daniel Yergin’s (The Prize, et al) annual Cambridge Energy Research Associates ’Tale of Three Seas’ oil and gas conference in Istanbul. The conference was packed with oil and gas heavies, ranging from the Grand Old Man of Caspian oil and the mastermind behind the so-called Deal of the Century, Terry Adams, to the regional business developer from Conoco, a shark-faced guy named David Huber and the head of the AES multinational electrical mission to Tbilisi, a lanky Englishman by the name of Mike Scholey. All laughed and cackled when I told them of my ride-thepipeline scheme, and even wished me well. None of them, however, could lead me any closer to the real BTC line than the generic red line from Baku to Ceyhan.

Then fate entered the lists. Arriving late to the main lunch featuring a keynote speaker talking about how Noah’s flood was really a wall of water rolling up the Bosphorus from the Aegean to the Black Sea (then just a lake), I found myself sitting next to a man who recognised me from a dinner with his wife a decade before. I explained my problem, and he told me to give him a call at his office, as he had something to show me. I did so, and he introduced me in turn to a colleague who had participated in an aerial survey of a prospective BTC route for a best nameless Oil Giant. Perched in an office on the upper Bosphorus, my newfound friend rolled out a NATO aviation map with the entire Baku-Ceyhan line detailed to exact longitude and latitude thanks to GPS, or Global Positioning System coordinates.

"Why are you showing me this?" I asked. "Isn’t it confidential?"

"It is supposed to be top-top secret," said the engineer. "But the bastards treated me like a tea-boy. We Turks have got our pride. So I made a copy, and decided to show you when I heard about your insane motorcycle scheme."

Equipped with the map and essential security information, I headed east, overland, walking (driving, really) the proposed pipeline route in reverse, bound for Baku and the annual June Oil Expo, which coincided with my arrival. In addition to schmoozing with the oilies in hopes of getting some corporate sponsorship for my venture down the BTC, I also had to solve a minor technical detail: locating some motorcycles to ride. Aside from some rural models working farmland like small trucks, traffic police drove the only Ural sidecar bikes I had ever seen in Azerbaijan.

With one exception: an export model painted a scruffy red, always parked in front of the BP/Amoco headquarters at Villa Petrolea. Friends told me it belonged to the manager for human resources and administrative affairs, a Scot named Ewen Patterson. I had never met the man, but he had been described as a gentleman of the corporate persuasion, who wore wire-rim glasses and sported a thick Scots accent when he spoke at all. In other words, about a zillion miles away from my....uhh...effervescent style. Once again, I seemed to have run into a dead end. Then one night, standing at a poolside Oil Expo reception and reaching for some more caviar and vodka, I sensed someone at my elbow, and turned to find a dapper, tight-lipped gentleman with a look of what appeared to be Presbyterian disapproval.

"My name is Patterson," said the stranger. "And I hear you want to talk about Urals."

Almost in a whisper, he informed me that he had heard about a warehouse on the edge of town that contained some eight motorcycles.

"They appear to have fallen off a truck in exchange for a debt," he explained with a twinkle in his eye. "I should be able to pick them up cheap - and I mean cheap."

"What does cheap mean?"

It is as if we are discussing a drug deal.

"I’ll buy the lot and you pay me back later," he said.

"Why?" I asked in amazement.

"Let us just say that I prefer fiddling with alternators to sitting behind my desk," he said with an impish smile.

I had just acquired the bikes!

But now I had new concerns, and of a rather compelling nature. Specifically, while I had managed to convince a bunch of oil field wild cats and weird guys that I was, in fact, an International Motorcyclist Extraordinaire, there remained one horrible truth I was still not quite yet willing to share with anyone.

Prior to organizing the BTC extravaganza, I had never been on a motorcycle in my life.