25 years ago, on the night of 25th to 26th February 1992, the town of Khojaly was attacked by Armenian separatist forces supported by the 366th Motorised Infantry Regiment of the former Soviet Armed Forces. 613 residents were brutally killed as they sought to escape in frozen temperatures through surrounding woods and fields. In the following article, Lithuanian journalist Ricardas Lapaitis describes arriving in the nearby town of Aghdam in the immediate aftermath and how the Khojaly tragedy changed his life.

Today marks 25 years since the day Armenian military forces, supported by the 366th motorised division of the then CIS, carried out the most bloody act of the entire Karabakh War – the storm of the Azerbaijani town of Khojaly. The Khojaly tragedy altered the fate of many people: those that were horrifically killed, as well as those who managed to survive that frightening night, and those that became witnesses to the bloody plans of Armenian nationalists. It was after this tragedy that I couldn’t remain indifferent and began my path in conflict journalism, later becoming a member of the Lithuanian Union of Journalists.

To this day I’m a representative of the International Eurasia Press Fund in Lithuania. Using my diaries, a group of international documentary filmmakers made the documentary Endless Corridor, a film about the fate of the residents of Khojaly which has received the highest nominations at prestigious international film festivals. I was awarded a diploma in 1993 and an award “for objective coverage of events in Nagorno-Karabakh.” The prize was awarded in Moscow. Two war correspondents were awarded posthumously; they were Leonid Lazarevich and Chingiz Mustafayev. The writer Yuriy Pompeyev also received an award. Besides this we gave interviews in Ostankino where we blamed the Kremlin for supporting the Armenian forces on Azerbaijani territory. The founder of the diploma and the award was the International Eurasia Press Fund. Azerbaijani women arriving in Aghdam having managed to escape from Khojaly, February 1992. Photo: Klaus Reisinger/COMPASS Films

Azerbaijani women arriving in Aghdam having managed to escape from Khojaly, February 1992. Photo: Klaus Reisinger/COMPASS Films

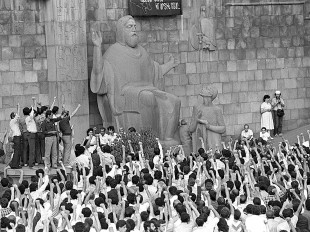

Baku, 1992

You could say that my path to Azerbaijan was initially chosen by fate. Before my trip to Baku I’d travelled around almost the entire Soviet Union. I went to the Urals, the Far East and visited the Artic Circle. I even went to Armenia itself immediately after the earthquake (the Spitak earthquake in 1988 - Ed). Already at that time I saw protests in Yerevan where there were slogans of “Karabakh is Ours.” I was amazed that even a disaster like this didn’t stop the Armenians from thinking of starting a war. Everything spoke of one thing: that the Armenians had been preparing for war for a long time. In Yerevan only bad things were being said of Azerbaijanis, and even in our press in the Baltics it was the Armenian position that was mainly being heard: that supposedly there was a religious war and the Turks were killing them.

At the beginning of 1992 I had the idea of travelling around the whole of Central Asia and then further east. I decided that the route would go through Azerbaijan, where I’d never been before, and then I wanted to cross the Caspian Sea by ferry.

It was a really bad time for tourism ; the country was in the heat of war

Of course, following the Armenian propaganda it wasn’t easy to make a decision like this, but I trusted fate. It was a really bad time for tourism; the country was in the heat of war. Every Azerbaijani had fresh memories of the horrific events of Black January (20 January 1990). And then came the Karabakh War, the first of its kind in the post-Soviet space. They called this the most troublesome spot at that time.

When I arrived, the railway station in Baku was in an unnerving state: there were lots and lots of people, everyone with tired, sad faces, women with small children in their arms, lots of things with them. Noise. Shouts. It was like some kind of rabbit warren…

I decided to look around the city, to write some notes in my diary and to travel on further. I set off for the city, where people had lost faith in their former country, in the former Soviet Union. Everywhere there was huge inflation, empty shops. As soon as the first few minutes, some young guys robbed me in the underpass, stealing some of my things and part of my money. After this I thought that I needed to find a quiet place. That’s how I turned up outside the Teze Pir Mosque. And then I was unlucky again. A priest approached and asked me to leave the mosque’s courtyard during prayers. I was preparing to leave when suddenly a young man came up to me. He said his name was Shain. I told him what happened. Having found out that I hadn’t decided where to stay, he offered me his place to stay. On the way he told me his sad story. Shain and his older brother had come here from Ordubad to study painting. Shain spoke of how he lost his brother during the events of January: he’d died under the tracks of a Soviet tank. This young man, 17 years old, was devastated by the loss of his brother. I tried to understand him and understood very well what price the Azerbaijani people had paid for their freedom.

I knew where I was going , it ’s just I didn ’t know what I was about to experience

Late in the evening we came to Shamsi Bedelbeyli Street, number 38. It was an old house without any comforts. In the middle of the room we saw a canvas with a depiction of Jesus Christ, a painting by Shain Babayev. I was amazed by the kindness of this young man who shared everything he had with me.

In the morning some of Shain’s friends came and, having heard about my misfortune, they collected some money so I could travel further. Sometimes they called me a Dervish. I didn’t really understand - what did this mean? Shain took me to see various people. From them I learnt a lot about the Karabakh conflict.

That’s how the terrifying news about the Khojaly tragedy reached me. I was only 23 years old myself then. I no longer had any doubts. I decided to go and see everything with my own eyes. I left my things at Shain’s place. I wrote him a farewell letter because I didn’t believe I would return alive. Early in the morning I went to the railway station... trains weren’t going to Aghdam any more so I bought a ticket to Barda. I knew where I was going, it’s just that I didn’t know what I was about to experience.

Women in Aghdam grieving in the days following the massacre. Photo: Klaus Reisinger/COMPASS Films

Women in Aghdam grieving in the days following the massacre. Photo: Klaus Reisinger/COMPASS Films

Aghdam, late February 1992

I arrived in Aghdam at night by bus. I didn’t know that martial law had been declared in the town. I wasn’t a journalist and actually this was the first time I’d been to a conflict zone. I didn’t have any experience at all and this was just after the Khojaly tragedy.

The local residents that had been on the bus with me dispersed and I was left completely alone in complete darkness. The town seemed like a deathly ghost... Snow was falling and it was very cold! I walked along this never-ending road and was looking for somewhere to spend the night. I was terribly tired and although I was wearing decent boots, my feet began to freeze. Finally, through a window I saw a small candle burning. I went in and saw an old man sitting at a table by the door. It turned out that this was the Aghdam hotel. He let me sleep on the floor in the hallway. Such was my arrival in Aghdam straight after the bloody events of Khojaly.

In the morning I saw that it wasn’t just me that was sleeping on the hotel floor. There were elderly people there, women and children, dressed in whatever they could find, all in a state of stress. I went out onto the street: the top floors of the hotel had been scorched and broken by rockets. Women were standing at the Aghdam mosque, crying and shouting in Azerbaijani. More and more Khojali survivors were arriving in the town... carrying children in their arms, some without shoes, frozen... everyone I spoke to was telling me such horrific things that at times I couldn’t understand what the attackers of this blockade-ravaged town were trying to achieve.

Even 25 years after this tragedy it ’s difficult for me to speak about it . Time heals wounds to the body but emotional wounds stay for life

Next to the mosque were rooms where the dead were being brought. Some people in uniform were standing there, with guns. They were crying as well. I saw a lot of coffins that had been prepared for the dead. And suddenly I noticed that a red stream was trickling from these rooms. I still didn’t fully realise that this was the blood of innocent people: women, children and elderly people. I was seized by a sort of horror. I was taken into one of these rooms. There were a lot of corpses lying there: an elderly woman with knife wounds on her body. A man with the top part of his head missing, his clothes had been burnt, his arms raised upwards, as though he were praying. Another man who’d been hit by a bullet right in the throat. He wasn’t wearing any clothes on the upper part of his body. In another room I saw a girl of about six. She was missing the top part of her head. There were deep wounds on her neck and below the waist. Her body was burnt, as though petrol had been poured over her on purpose. Another, even younger girl with eyes wide open; she had bullet wounds that were clearly visible. Another girl had simply frozen. On some were traces of mutilation: eyes cut out, fingers cut off. As I was explained, this is how the Armenians took rings off. I was in a terrible state of shock. I couldn’t come to over the next few days. Azerbaijani men peering into a makeshift morgue, set up to take the bodies of the victims of the massacre. Photo: Frederique Lengaigne/COMPASS Films

Azerbaijani men peering into a makeshift morgue, set up to take the bodies of the victims of the massacre. Photo: Frederique Lengaigne/COMPASS Films

It was in Aghdam that I met war correspondents from Baku such as Ilgar Jafarov, Oleg Litvin, Seydaga and many others. Most of the refugees from Khojaly were trying to go beyond Aghdam. Others were waiting for some sort of news about their loved ones. A third group was gathering money; the Armenians were asking for a 10-15 thousand-rouble ransom. They were exchanged for petrol and grain. All the Khojaly residents, taking me for a journalist, were asking me – What did they kill us for? For the first time I heard the phrase “Armenian fascism.”

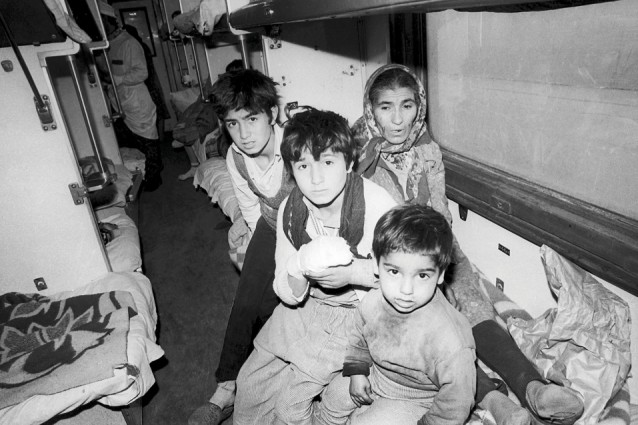

I also visited the medical train which had been equipped right on the rails outside the town. A colonel in the medical service called Jamaladdin Gurbanov showed me a book in which over 560 cases of amputated legs and arms had been recorded. He said that he’d served in Afghanistan but even there he hadn’t seen such horrific acts. The Armenians hadn’t spared women or children. In the train, the Khojaly survivors and those who had been exchanged told me ever more frightening stories. Nobody, even later, told me about a free corridor.  A woman and her children take refuge in a medical train in Aghdam following the massacre. Photo: Ilgar Jafarov

A woman and her children take refuge in a medical train in Aghdam following the massacre. Photo: Ilgar Jafarov

In the hospital in Aghdam, where medical examinations had been done on 181 dead people (130 men, 51 women, 13 children), I found out that no fewer than four corpses had been scalped. 10 had died from strikes by a blunt object. A body without a head had been delivered. The doctors said that cases of rape had been found of 13-16 year old girls who had been in Armenian captivity in Askeran, Stepanakert or private houses belonging to Karabakh Armenians. Crosses had been cut out on several corpses.

Even 25 years after this tragedy it’s difficult for me to speak about it. Time heals wounds to the body but emotional wounds stay for life. At that time many Khojaly residents said they envied the dead, especially those taken captive – they had without doubt gone through absolute Armenian hell. Ricardas (right) with Azerbaijani soldiers in the mountains of the Lachin region as they find themselves surrounded by Armenian forces in 1993. Photo: courtesy of Ricardas Lapaitis

Ricardas (right) with Azerbaijani soldiers in the mountains of the Lachin region as they find themselves surrounded by Armenian forces in 1993. Photo: courtesy of Ricardas Lapaitis

Vilnius, 1992

I didn’t want everything I saw and found out to just stay in my diary. The women at the Aghdam mosque who were waiting for their loved ones told me: Son, we don’t know who you are and where you’re from, but even if it’s just a small bit of news write about what you saw here... You know, this was enough for me to decide to return to Lithuania instead of travelling further. It wasn’t like now when there is Internet. I had to make a long journey in order to return to Vilnius by train and begin fighting alone against the large Armenian diaspora. My article was published in the leading newspaper Respublika, then in many magazines such as Nyamunas and Shvituris and each time Armenians appeared saying that it was a lie, that it wasn’t true. They even threatened me with my life. The Armenians openly said to the editor, Stanislovas Balchunas: We will hang Lapaitis. Later this editor tried to persuade me not to go to Azerbaijan and to stop publishing articles about it. He said: You’re so young and the Armenians will kill you.

Nevertheless I returned to Baku. I was helped a lot by a journalist from Bakinskiy Rabochiy, Eleonora Abaskuliyeva. Ayten Aliyeva, who was then working at the BBC and did an interview with me, translated it into English and sent it to Voice of Europe. They even added some music to my text. Umud Mirzayev helped me a lot in collecting information. In 1992, under a full information blockade and understanding the significance of distributing objective information, he created the International Eurasia Press Fund.

I stayed in Azerbaijan and despite the danger to my life and all the difficulties, at the first opportunity I would go to the frontline up until the middle of 1994. Even now I think - what were the Armenian forces, the architects of the storm of the town of Khojaly, trying to achieve? I think it wasn’t just an act to strike fear or take revenge. They perpetrated a frightening ethnic cleansing. This wasn’t the first Armenian terror against a peaceful population, but this time was different in terms of the scale of the crime against humanity. They crossed all the boundaries that could possibly be crossed. After Khojaly, in Karabakh, for Azerbaijanis the word “Armenians” alone became associated with death.

It was after the storm of Khojaly that it became practically impossible to sit at the negotiating table. This is what the Armenians were trying to achieve!

Azerbaijan, 20 years later

When a group of international documentary makers invited me to Azerbaijan, I travelled with them to the frontline area many times. There I felt a huge desire to return like 20 years ago with a rucksack on my shoulders and continue my work - collecting information about Armenian crimes against innocent civilians. When the film about Khojaly was ready I approached the International Eurasia Press Fund and asked them to send me to Terter. The Fund’s founder Umud Mirzayev helped me fulfil my dream!

What I saw in the frontline area went beyond all my expectations. Afterwards I spoke a lot about this when another organisation, The European Azerbaijan Society (TEAS), invited me to Strasbourg, Brussels and Paris. In front of a large auditorium I spoke about how people live now around the Armenian-occupied territory. Shooting at nearby villages, setting fire to wheat fields, sabotage and minefields have become a daily reality there. Armenian dugouts are sometimes at gunshot distance from apartment blocks and farmers’ fields. They fire without warning, innocent people die. All this happens in front of the global community’s eyes. Armenia is not subjected to any sanctions. There is nothing to compare here with Ukraine, where various sanctions have been imposed even against Russia. On top of this, their soldiers control the Sarsang Reservoir and in the summer they direct the water along a different channel. Almost the entire large Terter region, as well as other regions, experience a great lack of water. The Armenian nationalists behave how they want beyond this too. The only people that put up any resistance are the Azerbaijani armed forces.

I’ve done a lot of interviews with Azerbaijanis from different regions. I’ve questioned former prisoners of war, one of them had been held in the women’s prison in Yerevan. Illegal imprisonment is still practised by the Armenians. They don’t just shoot at the frontline regions near the occupied area of Nagorno-Karabakh, but also at the Tovuz and Qazakh regions. Their aim remains the same - to create panic and discomfort for Azerbaijanis’ daily life. Their aim is to occupy as much foreign territory as possible.

The brash, openly military rhetoric of Yerevan influences the lives of the new generations. I’ve seen drawings by children with Armenians depicted as terrorists and murderers. That’s how they’re viewed by children living in the frontline area. All Azerbaijanis living near the frontline have one question: How long will this continue? In the Tovuz region I visited a school which is sometimes even shot at during lessons.

Sadly, many human rights organisations keep silent or create the impression that they’re working, by constantly talking about a peaceful resolution of the conflict, but in reality they’re more often doing nothing!

In all my many years of journalism in Azerbaijan I’ve never sought any benefit for myself. I haven’t sought important connections. For me the most important thing was and is speaking to simple people. Although, in 1993 I met Heydar Aliyev, who was head of the Supreme Majilis of the Autonomous Republic of Nakhchivan. The interview was published in a leading newspaper in Lithuania, Lietuvos Rytas. I also met the then president of Azerbaijan, Abulfaz Elchibey. Both leaders of the country left a good impression on me. My relationship with Azerbaijanis is really quite unique. All this is hidden in Eastern wisdom and philosophy. It’s as though I‘ve grown roots here, even the mountain air and desert has become a part of me! And most importantly the truth in this conflict is with the Azerbaijanis and I believe in justice.

Leaving Azerbaijan in that long-ago 1994 I asked my friend Shain: How much is your picture? I understood very well what this young man who had lost his brother was feeling. After all, he’d painted the picture thinking of him. Shain replied that for him it was priceless. There was no amount of money that could buy it. I understood him. And suddenly he said to me: But there is another possibility, I can give it to you as a gift. Even now it’s next to me as I write these words!

For Azerbaijanis, Karabakh and the entire occupied territory is simply invaluable. They will never forget it, never give it up, they will fight for it to the end. For them this land is like their mother and father, it’s as essential as air, fire and wind! And the most interesting thing is that when this territory is liberated, Azerbaijanis will share all the blessings of this one-of-a-kind corner of the world. They will invite everyone to visit and give the best of what they’ve received, together with their native mountains. That’s what these people are like, as I found out when they were in difficulty. I also dream about returning to Nagorno-Karabakh. And I believe that sooner or later Azerbaijan will restore its territorial sovereignty.

Sometimes some people say to me that I shouldn’t interfere in other people’s affairs and that this is a foreign war. I reply to everyone that there is nothing scarier than indifference. For me there is no pain which is foreign. There is no difference between religions because we are all people. And we all have an equal right to life, freedom and our home!

About the author: Ricardas Lapaitis is a member of the Lithuanian Union of Journalists, a correspondent for the newspaper Dzuku Zinios and president of the Lazdijų menė writers’ club. He is the protagonist of the documentary film Endless Corridor in which two journalists return to Azerbaijan 20 years after covering the Khojaly Massacre. Between 1995 and 1998 he also covered the war in Chechnya.