As 2017 marks the 200th anniversary of the first German colonies in Azerbaijan, Narmin Mahmudova managed to track down one of the country’s last Caucasian Germans. The following article recounts her remarkable life story...

It started when my mum’s doctor colleague and friend told me: My grandmother is German. She’s spent almost all her life in Azerbaijan and lived an interesting one; she’s been through so much, just like in the movies.

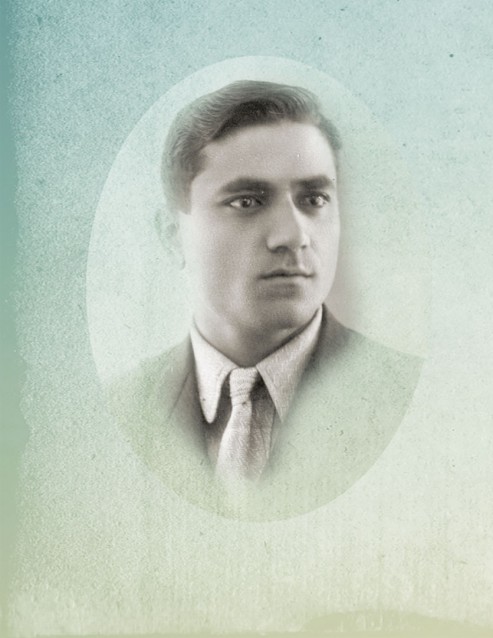

Family photo taken in Kirovabad (now Ganja) in August 1938. Front row: Bahadur (middle) and Ida’s sister Yelena (to the right). Back row: Dilshad (middle) and Ida (to the right) Ida (right) and her sister Yelena as children

Family photo taken in Kirovabad (now Ganja) in August 1938. Front row: Bahadur (middle) and Ida’s sister Yelena (to the right). Back row: Dilshad (middle) and Ida (to the right) Ida (right) and her sister Yelena as children

This happened exactly as I was about to finish my previous article. Dr Lutfiye, granddaughter of Ida, the heroine of my story, knew that I was looking for interesting themes, especially stories about women. Without hesitation I promised to drop in soon for a chat and within a month she sent me a book written shortly before, called A Century–Long Story. This book, the incarnation of Ida’s whole life, her ancestry and descendants, is something like the saga of two families, the Lehmanns and the Hanns, which passes smoothly into the saga of Ida and Bahadur, because once Ida met Bahadur she was tied forever to Azerbaijan, which she still considers her only motherland.

The Lehmanns and the Hanns

This year marks 200 years since the Germans first settled in Azerbaijan, although the history of German settlement within the Russian Empire started long before. There were thousands of German settlements there before World War I. Many Germans had moved to Ukraine and Ida’s great grandparents on her father’s side were among them. Her grandfather, Gotlob Lehmann, was a wealthy businessman who owned a flotilla of trade and passenger ships. His son, Alexandr Lehmann (Ida’s father), handsome and rich, was an eligible bachelor for that time, but he was unlucky - he was 35 and still couldn’t find the love of his life. His future wife, the 26-year-old Lidiya Hann, had also been unlucky in her search for marriage, the death of someone she loved dearly had overwhelmed her. However, one meeting was enough for them both to understand: it’s never too late to love.

That’s how, in 1923, exactly 94 years ago Ida was born in Krasnograd, Ukraine, to Alexandr and Lidiya Lehmann. Her sister Yelena was four years older. As Ida recalled later, they lived and were raised in a “palace.” Despite having plenty of staff in the house, the two sisters were taught to run a household from an early age.

Ida always remembered her life as full of movements and partings

Ida remembers her life as being full of moves and partings. Very soon her sister Yelena moved to Kharkov to study at medical school while Ida’s father was also looking to move as his business was doing badly and the mass starvation in Ukraine was making itself felt.

In 1932 Ida’s grandparents (the Hanns) moved to Helenendorf (now Goygol) in Azerbaijan. Four years later, Alexandr decided to visit them and at the same time look for work and a place for Ida to go to school. Azerbaijan was a convenient place to live as German settlements already existed in parts of the country. One of them was Traubenfeld (now Tovuz), a German name that means “grape field,” as Tovuz is the home of viticulture in Azerbaijan. Nargiz, Ida’s daughter, recalls that the Baku-Tbilisi railway station divided the settlement into two parts: Azerbaijanis lived on one side, Germans had settled on the other, there was a park and a cinema… Life in Taus (Traubenfeld or Tovuz - Ed.) thrived, there was a famous cement factory releasing products of high quality…

On his arrival Alexandr managed to get hired as a mechanic. He was provided with accommodation so that he could stay there with his family. Who could imagine then that this move would decide the rest of Ida’s life?

The Germans lived in one-storey buildings. Ida was studying in year six at the time and there in Tovuz she could continue her studies by attending the German school. The house was cramped, life wasn’t the same, but on the other hand her neighbours turned out to be very kind and noble people – uncle Gasham and his wife Khava.

Their daughter Dilshad became Ida’s close friend. Despite the cultural and religious differences the two neighbours loved each other sincerely. Here Ida encountered Azerbaijani culture and learned the Azerbaijani language. She remembers those happy childhood days when uncle Gasham and his family celebrated the Novruz holiday and Ida impatiently looked forward to getting another Novruz khoncha with national sweets - shekerbura, pakhlava, gogal - which uncle Gasham used to bring them. Each day Gasham and all the other neighbours came to the Lehmanns to pursue the male patime of playing nard (backgammon).

Unfortunately, this amiable family was then caught up in the black wave of the 1930s. Uncle Gasham served the authorities, working in a high post, and nobody could ever imagine that he would be arrested as an “enemy of the people.”

Gasham’s family was large – he had 10 brothers and sisters. One of his sisters, Fatima, lived in the same courtyard. Fatima and her husband didn’t have any children, so after she lost her parents they took her small brother Bahadur into their care. As a child Bahadur ran errands between the Lehmanns’ and Fatima’s houses. Fatima would send him to the German neighbours with something to be sewn or to borrow things. Meanwhile Bahadur grew into a tall, handsome, young man, and the girl next door was pretty and blonde with blue eyes – not like the others. There is probably no need to write how they fell in love.

At one point both made a decision – not to leave each other whatever happened. Bahadur was about to graduate from the Lenin Institute of Railway Transport Engineers in Tbilisi. He had just been offered a good job in Rostov but leaving Ida wasn’t in his plans. Ida was afraid of her parents. She was only 15, too young for marriage. Just then her parents moved to Kirovabad (now Ganja) because of her father’s new job. Although Ida was used to changing apartments, this time everything was different … Bahadur was far away from her.

A decision was made to marry secretly. And an escape was planned: Ida had to persuade her parents to let her go back to Tovuz to attend a wedding. It worked. There, Bahadur was waiting for her with great excitement. It was 1938 and they were in love and married, connected once and for all by the marital bond. With that Ida left school and the happy couple left for Rostov in search of a new life. Both sets of parents were upset by the secrecy and didn’t talk to them for a while. Ida’s parents stayed in Ganja until the war began.

New life, new movements

In Rostov, with the help of a close friend, Abbas, Bahadur was hired to work at Chertkovo station. As the brother of an enemy of the people he was in danger and tried to hide this black mark in his biography.

The train moved, carrying away plenty of broken and lonely hearts into the unknown

One year later Nargiz was born. They lived a good and happy life, Bahadur worked hard, with love and warmth Ida performed chores, trying to take care of every member of the family. But everything failed when the Soviet authorities decided to award Bahadur as a good worker and his black mark was found.

Maybe they would have had a hard time if one of their friends hadn’t immediately warned them. So they moved to Abastumani, Georgia, where friends helped Bahadur to find another job. Here, in one of the local schools Bahadur taught physics and maths, and Ida also taught local women to read and write in Russian.

Before the war Abbas helped Bahadur and Ida return to Azerbaijan. They managed to visit both families – relatives in Tovuz and the Lehmanns in Ganja. As soon as they saw their darling Nargiz, they forgot all previous wrongdoings and were happy for their homecoming. Bahadur returned to his specialism: he was entrusted with the construction of the railway from Salyan to Astara. Thus the family stayed in Salyan.

As the war approached the Germans became afraid of the rapidly changing political situation. But Ida never complained; she repeatedly mentioned that she was never treated badly in Azerbaijan. Everyone loved and respected her for her kindness, sincerity and hospitality.

Everyone loved music in the Hann family. In this photo are Ida’s mother Lidiya (left) and her sister Matilda (right)

Everyone loved music in the Hann family. In this photo are Ida’s mother Lidiya (left) and her sister Matilda (right)

But when the war began deportation became inevitable and suddenly one autumn all the Germans were given only three days to prepare: they were told to pack warm clothes and allowed to take only up to 20kg. Bahadur couldn’t leave work so he sent his brother Bahram to accompany Ida to Kirovabad. Fortunately, Ida arrived in time to say goodbye to her family. She didn’t know where they were being sent or how to help them. Ida was allowed to stay as she was married to an Azerbaijani. She was only 20 when on the morning of 10 October she and her two-year old daughter Nargiz pushed through a large crowd of people looking for her parents and sister Yelena.

Imagine the picture: a long row of men in uniform and a crowd of dumbfounded, frightened faces hopelessly trying to get through the barricade. Suddenly Nargiz let go of Ida’s hand and rushed through the uniformed men. As would any mother, in panic Ida ran to catch her, seeing her whole life pass before her until she understood: Nargiz had recognised her grandparents and rushed to them. Bursting into tears they hugged and kissed their favourite granddaughter. At that moment Ida didn’t know she would never see her father again. As soon as they said goodbye to each other, Ida with difficulty managed to persuade one of the men in uniform to retrieve her daughter for her. None of them knew where they were going, for how long and if they would ever meet again. The train moved off, carrying with it so many broken and lonely hearts into the unknown.

Ida & Bahadur

It was only a year and a half later that Ida received a letter from her parents, saying they were in a village in Kazakhstan. They stayed there until 1956. Meanwhile, in 1945, Ida and Bahadur had a second child – Farhad. They still moved from one place to another. In Alat they were lucky again to have a neighbour from the NKVD (People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs, forerunner of the KGB) who was a good man and later they became friends. Bahadur was very good at making friends – wherever they went friends always came to their aid. They truly loved Bahadur and took risks to help him.

“Azerbaijan is my only motherland, what have I got to do in Germany?!”

Imagine, on the one hand he was the brother of an enemy of the people, on the other – his wife was German. Ida was aware of how much trouble her nationality caused – wherever they went they were under supervision, wherever Bahadur wished to work he was reminded of his wife’s nationality and even when he worked he was never promoted. Ida also suffered – she wasn’t able to go out. Instead, Bahadur brought and did everything. Sometimes at night people in uniform drummed at the door demanding to see their documents. But they never regretted being together; Bahadur was totally loyal to his wife, nothing could ever make him leave her. Years later he told her a story of how one of his ex-supervisors had advised him to divorce his wife. In return Bahadur would be promoted; the supervisor even suggested a new wife. Bahadur’s answer was short and clear: I love my wife and will never leave her!

Both tried hard to take care of each other. Bahadur loved to buy presents for Ida and often brought flowers and others of her favourite things. They were inseparable, they loved reading books (he was a bookworm) and, later, watching their favourite television programmes together. Ida even helped him with work: the end of the year was the time for giving reports, she had beautiful handwriting and so they filled out the papers together.

Ida had to wait until the end of the war to reunite with her family. In the early 1950s, after Stalin passed away, life started changing for the better. Those exiled were allowed to meet relatives. Ida was fortunate to have Bahadur, in such tough times he tried his best to encourage his wife. He found a way to take her to see her family and despite the long, hard journey it was worth it. It is hard to express how touching the reunion of the Lehmanns was. By that time Nargiz and Farhad were already at school, in exile Yelena had got married and now had a family. They spent two happy weeks together, but didn’t know what to expect.

Finally in 1956 the exile came to an end. By then, Ida and Bahadur were living in Neftchali. She was always grateful for Bahadur’s concern – he invited the Lehmanns to Neftchali where he worked at the railway station. Everyone was happy, Bahadur arranged a separate apartment for them and later they bought a house. After a while Bahadur was sent back to his hometown of Tovuz as head of the railway station, so they returned to where a long time ago their story began. After so many displacements, only in 1971 Ida and Bahadur started building their own house. As he was busy at work all day, Ida supervised the building process, paying attention to every detail. Her dream came true.

As her relatives recall today, their house was like a headquarters – living next to the railway station brought a large influx of people - from nearby settlements, friends, relatives and co-workers, they ate and drank and shared the latest news. Everyone knew and respected Bahadur and his family. Nargiz says that her mother never complained about all the people: it seemed like she lived it, she loved it. Every morning the house was filled with an amazing smell. She cooked perfectly, our basement was full of various pickles, jams, baked goods, our garden was a paradise – it was full of the most varied fruits and vegetables, each of them neatly planted in beds…

Last years

1988 was the year of their 50th wedding anniversary. The next year Ida and Bahadur were lucky to see their great granddaughter’s birth. Unfortunately, those were the last happy years together as Bahadur fell ill. He never confessed to how bad he felt, perhaps not wanting to upset his beloved wife.

Ida’s home, recently noisy, full of guests and laughter, now seemed empty and lifeless. Her relatives persuaded her to leave Tovuz for Baku, which wasn’t easy – she had lived there happily with Bahadur for 30 years. When I asked, did she ever go back to Germany? The answer wasn’t long in coming: No, she never wanted that. Throughout the rest of her life she had the chance to leave for Germany but didn’t. She kept saying, “Azerbaijan is my only motherland, what would I do in Germany?!”

German ambassador Klaus Greulich accompanies Ida after the embassy event in honour of German reunification

German ambassador Klaus Greulich accompanies Ida after the embassy event in honour of German reunification

However there is a famous story of how she met the German ambassador, Klaus Greulich, in Baku. Greulich was looking for Germans in the Azerbaijani regions when he was suddenly told about an old German woman living close by. He and some representatives immediately asked for a meeting. A little later they visited Ida and were stunned by her pure ‘gothic’ German, a language she hadn’t used much since her marriage. Over such a long period of time it hadn’t been affected or become mixed with other languages; without realising, she had preserved the old, classic German language. Later Ida was invited to attend a big event in honour of German reunification. All the embassy staff surrounded her and the ambassador and his wife accompanied her throughout the evening. As she confessed later, she was treated like a queen that night.

When I had the chance to meet Ida, her children Nargiz and Farhad and her granddaughters, we talked without noticing four hours pass by. I loved this family for many reasons: they are friendly, they love their “Mum Ida” and the late Bahadur and remember lots of the stories Ida used to tell while her memory allowed. They do their best to preserve them all and pass them on to the next generations. Ida is old enough now that she hardly remembers her stories, the stories I am telling you now, but she is sweet and shining, she is still full of life. Imagine, when I entered she welcomed me in three languages!

About the author: Narmin Mahmudova is a young writer with an interest in women’s issues. She is grateful to Ida and her family for their kind cooperation and interviews, and acknowledges Gulya Taghiyeva, whose book, A Century–Long Story, was a key source in writing this article.