Back in China, I had done quite a few interviews with artists and reviews of exhibitions throughout my four years’ experience as a journalist. So when I decided to do one with contemporary artist Faig Ahmed, I was pretty sure what to expect. I revisited his exhibition, went through the press release, checked everything on his personal website, searched all related information in as much detail as possible, categorised the data at hand and made a perfect outline for my interview.

All that remained, as I finally strode into his studio full of confidence, was to fill in some blanks and weave them into an article. But as the old saying went: when we are overwhelmingly optimistic about something, life shall always teach us a lesson. I had prepared the traditional routine for my interview, but there was nowhere to fit Faig in. He was someone that can never be “prepared.”

Our interview took place on a late afternoon at his studio, steps away from Icheri Sheher (Baku’s old city – ed.). The large windows of the old architecture allowed in threads of light, yet the spacious room remained quite dark on a very cloudy day. Rugs of all materials, patterns and shapes were so scattered across the desk, walls and floor that I almost accidentally stepped on one which accentuated a strong oriental touch.

Casually reclining on a sofa, we opened our conversation. Believing that what makes the art far outweighs the importance of what the art is, I began with a tentative study of the ideological base underlying his artwork. Thus a mystic path gradually revealed itself, leading to his …

... Metaphysical world

Growing up in a secular family in Sumgayit, Faig felt free to make choices and important decisions from a very young age thanks to his lenient parents. As early as preschool, he already demonstrated his outstanding talent for art by drawing randomly all over wallpapers. At 15, he started to try different jobs while still at school.

He has been a Christian, a Buddhist and a Muslim, but religion for him is more a medium for inner quest than doctrines or rules for self-discipline. He even considers art to be a new religion - a belief that artists adhere to exploring the outer world and themselves. He is also interested in various philosophical or religious ideas, such as Vedanta, Sufism and Taoism. Tao Te Ching is among the five most influential books in his life, whose teachings he still follows every day. He can even augur using methods in the I Ching or Book of Changes.

Through his rich experiences and multiculturalism, he has developed his peculiar insight and ideology, which is crucial to an artist:

I believe everyone is unique and artists are just ordinary people who see things from different perspectives. One’s perception of art has nothing to do with intelligence. Even though you may not understand the artwork, you can feel it and that only concerns your aesthetics.

Everything is connected. For example, the craft of carpet making doesn’t belong to one nation, say Azerbaijan or Iran, it is a cross-border product of human civilization as a whole. The traces of different cultures are detectable in carpets through the development of their patterns and weaving skills.

The whole world is dualistic. All things have two sides that interrelate and counterbalance to achieve harmony, such as Yin and Yang, fullness and emptiness, rules and freedom. The significance of art as a creative activity lies in two complementary parts: the broader humanity level in which art serves as a tool for the human race to question and settle social problems. The second level is within the artist himself: he goes down to the very bottom of his spiritual world for self-analysis and self-improvement.

If things go to extremes, they will convert to the opposite side, so we’d better stay in “the middle way” - an eclectic method of doing things. Keeping a proper distance offers both detachment to see things clearly and leeway for the self-protection mechanism.

Showing me his sketchbooks containing the primitive ideas of later masterpieces and other random drawings, he said that he also did these sketches halfway between consciousness and sub-consciousness, another level of “the middle way,” which is a notion in Chinese philosophy that advocates not going to extremes, learning from different opinions and having a peaceful mind.

The influence of religion and philosophy can be clearly seen in his first solo exhibition (also his personal favourite) named Points of Perception in Rome, Italy, last year. Sufism was at the core of this exhibition, which featured a large-scale installation and many other individual works. Accompanied by a ghostly lyric composed by the artist from nine vocals and instruments, Faig, like Dante in the Divine Comedy, led the audience through the netherworld with concepts of blurred space and time in search of truth and the world of spirits. The dominating, gigantic carpet with a backward curve represented a regression to one’s heart and the scriptures and, along with the ascetic behavior of the artist walking on nails, helped to achieve mental sublimation. By enlarging the audience’s senses to perceive things they had never seen before, the artist bridged the border between mysticism and reality.

Besides philosophy, Faig is also a science fanatic. Majoring in sculpture, he has a good knowledge of geometry and key concepts such as space, angles and perspective prevail in his work besides sculptures. Drawing from quantum physics theories, Faig considers human beings small particles in a vast universe; similarly, each knot in a carpet resembles a single pixel among the whole composition.

My purpose is to present things objectively the way they are and let the audience have their own understandings and interpretations

Asked how he had so much time to accumulate his abundant, multi-discipline knowledge, Faig laughed and replied that it was totally out of interest. He wakes up every morning strongly motivated to learn and create something new.

Though he was reluctant to associate himself with carpets and even forgot the exact year in which he started making them, this traditional symbol has played a big role in his career, which ushered in the next phase of our interview…

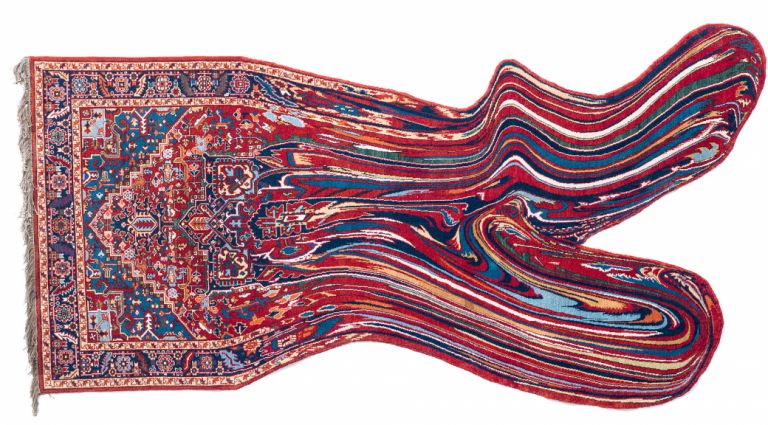

Carpets in deformation

Over a decade ago, Faig was seeking some influential and experimental media to express his ideas and the carpet came to his mind:

Firmly connected with ordinary people’s daily life, it is a huge metaphor representing everything, social structures and people’s way of living included. Besides, it was a new material that very few artists were applying then.

Most of Faig’s carpets are based on traditional patterns with symbolic meanings:

I’m very interested in the origin of languages and human writings. Languages are carriers of culture and thus affect the way people think. I’m a self-taught student of Sanskrit, Arabic, languages of Scandinavia and Central Asia. It was the study of pre-historic petroglyphs that led to my fascination with the language of carpet patterns.

I often resort to classical carpets, say Persian carpets, for blueprints, and then make innovative mutations. My linguistic knowledge helps me a great deal with a better understanding of the codes that ancient carpets are transmitting. Currently I’m designing some patterns evolving from Chinese hieroglyphs and I plan to go to Tibet for more inspiration and specific ideas this year.

The use of distortion, exaggeration, deconstruction and reconstruction techniques in order to achieve artistic effects such as liquidity, geometry, symmetry, pixel and graffiti is a recurring theme in Faig’s rugs:

By these deformations, I don’t mean to revolt against tradition. Carpets are stable records of our history, so it’s interesting to juxtapose them with unstable elements such as a technical glitch yet still see things achieve coherence and harmony. My carpets were initially visual and straightforward in expression, yet now I strive to take them deeper and also I prefer to minimalise the visual “lies” to reveal their true nature. The installation named “Virgin” at the Yarat exhibition is an example.

Faig disclosed to me the secret of making his magic carpets:

For some of the carpets, I simply make sketches or even just narrate to the craftsmen; for more complicated ones, however, I sometimes design the patterns by computer.

It was no surprise to learn that Faig can weave, although he doesn’t do it very often:

Craftsmanship requires plenty of time and patience. When the craftsmen are working, they are in a meditative mood, focused exclusively on one thing. The repeated sound of carpet making is rhythmic and lyrical because of the strength required to weave distinct patterns.

In the last part of our interview, Faig briefly talked about his latest exhibition at Yarat, in which he played the role of a daring pioneer to…

Speak the unspoken

Entitled Nə Var, Odur, or It Is What It Is, Faig’s solo exhibition at the Yarat Contemporary Art Centre (running from November 2016 – January 2017) was an analysis of gender relations and social customs within traditional Azerbaijani communities. The title originated from an old Azerbaijani saying emphasising a sense of imperturbability and an attitude of accepting things the way they are.

Ten curtains with traditional gilded patterns veiled the gateway to a world that is slowly dying away. Mistily concealing what people are unwilling to speak about, the Curtain In-between induced the viewer to step out of their comfort zone and confront taboos central to Azerbaijani society.

In the first exhibition hall, two installations echoed with each other from a distance. Entitled AZMAN (The Biggest), the monumental installation featured a field of highly decorated sugar cones. Sugar cones are usually given as a gift from the groom’s family to newlyweds on their wedding day to be consumed upon the birth of the first male child, as a symbol of fertility. The cones are a representation of masculine power while their decorations suggest a female presence. Through the changing scale, Faig vividly portrayed the highly centralized male-dominated social structure.

In a corner of the same room, a hand-woven carpet entitled Virgin spoke, on the contrary, from a female perspective. Here Faig again used his skills of deformation to distort the rug’s upper, traditional pattern into its lower, thick red mass. This work was rooted in the early practice of unmarried girls producing a piece of exquisite textile as her dowry. The change in colour and form symbolized the maturity and aging of young girls.

Covered by another curtain and sparsely lit, exhibits in the second room were arranged in a rather private manner, as if someone from a remote place was whispering their secrets into your ears. By presenting items symbolic to a girl’s life, including mattresses and a silk scarf, both Nine Nights and Silk Way alluded to the position of women in society with a reference to their subtle psychology.

Opposite Nine Nights was a screening of the video Social Anatomy. At the Crystal Hall, Faig directed a performance composed by a compendium of rituals typically done during weddings and funerals in Azerbaijan. He then filmed the performance through an air view camera. Framed by a rectangular piece of green and red fabric, the symmetrical setting bore a salient resemblance to an Azerbaijani carpet seen from above, with each anonymous performer representing a knot in the large carpet, devoid of their own individual personalities. The repeated circulation of the performers’ movements from weddings to funerals represented the circle of life.

The concealed finale of the exhibition was situated behind the screen of Social Anatomy under the title Small Wedding. Hanging on an unreachable height behind small red cloth curtains, seven drawings allowed viewers, with the help of a ladder, to peep into the bloody ceremony of circumcision for boys reaching a certain age.

As a commonplace ritualistic practice in many countries including Azerbaijan, this big moment, like the blossoming of a flower, signals a new stage for a grown boy yet may also trigger traumatic feelings and cast life-long shadows as a humiliating process. Some of them, such as young gay men, are forced to surrender their free will by the existing social framework before being able to figure out their identity, according to Faig.

In order to investigate the symbolic gestures, rituals and objects specific to some old Azerbaijani social customs, Faig went to Sheki, Basqal and Khinaliq to carry out his research.

I don’t want to be judgmental about these traditions. The world changes every day, including our values. Certain things survive while others gradually disappear into history. Even widely acknowledged morality differs from region to region. In some African anthropophagi tribes, for example, eating human beings is morally acceptable while in most other areas it is definitely an atrocity.

Whether you like it or not, it is there. My purpose is to present things objectively the way they are and let the audience have their own understandings and interpretations.

The future

My interview concluded with Faig’s remark on his future plans:

I shall launch a new exhibition in Sweden in May. The Carpet Museum also sent me an invitation to create something new in the coming year. There are other invitations as well. A lot remains to be done yet I will focus on one or two selected projects each year to fully realise them.

During our three and half hour-long conversation, I tried more than once to drag him back to my regular interview mode but all in vain. As I finally gave up imprisoning his free thoughts and started to follow his brainstorm, I found his physical image recede into his metaphysical world and all I could see were his winged ideas. Like his seemingly loose desktop, deformed carpets or interest in the haiku literary form - plain in shape yet profound in meaning - his train of thoughts forms an ideological system at times incomprehensible but also tremendously fascinating.

As I finally gave up imprisoning his free thoughts and started to follow his brainstorm, I found his physical image recede into his metaphysical world and all I could see were his winged ideas

Though a big challenge to my journalism career, I feel deeply honoured to have met him and weaved his fancy ideas into a peculiar carpet of experimental writing. Some artists exhibit their work carrying specific messages they would like to share, while very few others generously show us their whole world, which is infinite and marvellous. Faig Ahmed is one of them.

About the author: Wu Hui is a teacher of Chinese language at Baku State University dispatched by China’s Minnan Science & Technology Institute via the Hanban programme.