Yusuf Heydar Oglu Mammadaliyev was an academician and an outstanding scientist who made a number of discoveries of global significance in the field of petrochemistry. He was a winner of the State Award of the USSR (1946) and the inventor of high-octane gasoline which played a major role in fuelling aircrafts during the Great Patriotic War. He twice served as head of the Azerbaijan Academy of Sciences (1947-1951, 1958-1961) and was the rector of the Azerbaijan State University. In 2005, at the initiative of First Lady Mehriban Aliyeva, his centenary was celebrated at the UNESCO Headquarters in Paris.

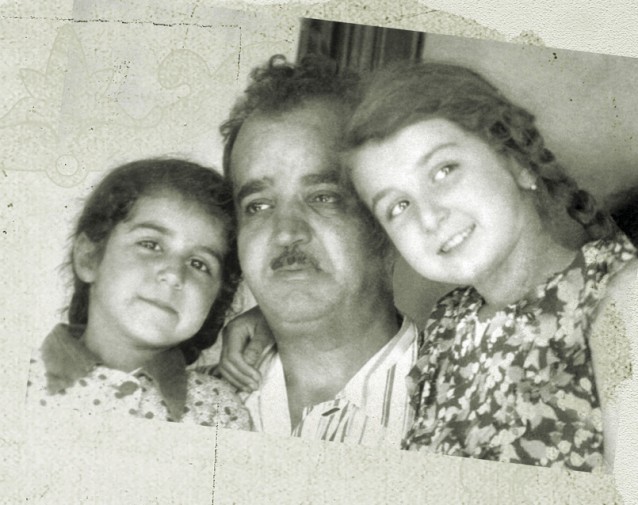

It’s always difficult for me to write about my father because my whole childhood and all the time he was with us is painted in such bright colours that it’s difficult to put them into words. As children we knew that our father was a scientist known all over the country and we were proud of him. But above all he was a loving father, a great friend and a man with whom we discussed all our problems. We were especially happy on Sundays because he spent them with us. We woke him up early in the mornings, sat at his bedside, and he told us stories, fairytales and legends, and recited verses from great poets. All of them were about fidelity, friendship, honour, debt, and love for the country and those close to us..

Above all he was a loving father, a great friend and a man with whom we discussed all our problems

He wrote: I received your letter and the “rose” card on the back of which you wrote: “Daddy, look at these roses and remember me.” I remembered an ancient legend, Eastern, written in the 11th century. According to this legend, two faithful, loving friends give each other a violet and a rose. The one that gives the violet says: “I will be eternally faithful to our friendship. Accept it from me as a special sign. Remember our friendship wherever you see fresh violets. You will become as blue as this violet with your head bowed if you betray the trust of our friendship. And I will take a rose as a sign: every time I see it in my garden, I will remember this day and our friendship. Let my days be as short as those of the rose if I forget you even for one day.”

I don’t for a day, not even an hour, forget you, my three little ones - Gunel, Sevda, Rena, and of course your mother - my great friend.

He loved poetry and literature very much. It’s well known that he wrote verses in his youth and was going to make literature his profession. That’s probably why there were many poets and writers among his friends with whom he met very often. They usually stayed in father’s room until late at night having long conversations.

Among his friends were Samed Vurgun, Mirmekhti Seidzade and Mikhail Rzakuliyev. One day Samed Vurgun, an avid hunter, brought us a little jeyran as a gift. As children we were delighted with the present, but we soon understood why the adults didn’t agree to keep it at home. Then I read a story about what had happened to Samed Vurgun when hunting. Having shot a jeyran, he saw how its cub began to fuss around its wounded mother and how a tear rolled from the mother’s eye. After that the poet swore never to shoot animals again.

There’s a poem of my father’s in which he laments his fate, not letting him become a poet and dragging him into science, but he notes that the poetic achievements of his friend Samed Vurgun are his consolation. My father had a broad range of interests. For example, everyone knows about his interest in painting. He befriended a very young Tahir Salahov who had just returned from studying in Baku and had already achieved great success as a talented painter. Many years later, Tahir Salahov was heavily involved when the monument to my father was being sculpted and it owes much of its grace to him.

My father took us to all the exhibitions and opening days. There are some remarkable books on art, which he collected all his life, stored in his room. Mikhail Abdullayev, the academician and People’s Artist of the USSR, wrote that he was always amazed by how well my father understood art, judging from time to time like the best of art critics. Stopping in front of a picture at exhibitions, he would ask us, What do you think of this picture? My father’s desire to know our opinion gave us great pleasure. He often invited us to try to write verses on various subjects. We agreed willingly and then recited them to him, awaiting his assessment with impatience. He listened to us carefully, then began to explain how best to use rhyme and taught us to express our thoughts and feelings correctly.

My father was very fond of photography. It was his hobby. He always took a camera with him on trips and city walks, preparing for it very seriously in advance. At home we keep many of father’s cameras, and too many films to count. We managed to fix up some of his photos and they were exhibited at an exhibition of his photography at the UNESCO headquarters. They were appreciated by viewers and experts very highly. He wrote: Only a well-rounded, educated scientist can be considered a good scientist.

He also liked to dress well. His contemporaries and pupils can confirm his special attitude to clothes. He was in Spain on a business trip, and this was the time of the thaw, when Soviet scientists began to travel abroad and very much differed from Western people in appearance. All the local newspapers in Spain then wrote about the Azerbaijani scientist, highlighting not only the unusual nature of his research, but also his elegance, fashionable suit and cultured manner. He paid attention to our appearance too. Considering the fashion of that time, he let me and my sister, teenage students, cut off our braids, which was a real revolution in the family and a great delight for us. He was probably a great romantic, because he could even romanticise a science as exact as chemistry.

He wrote: You know, in the history of chemistry there have been many sayings about the greatness of this science. A great 19th century scientist said: “I see chemistry as a dense forest, full of wonderful things.” And you see, my dear, each seeker strives to find in this dense forest a new creation of nature, a new feature of life. These searches and discoveries give infinite, incomparable joy.

He fell in love with my mother when she was still a student at the conservatoire. They met through the family of my mother’s uncle, the professor and microbiologist Ismayil Akhundov, with whom my father developed a medicine to treat patients with malaria. This sickness was rampant at that time in Azerbaijan. My mother was very beautiful and played the grand piano very well. She won the young scientist’s heart at once. Not even Mir Jafar Bagirov’s (Bagirov was the communist leader of Azerbaijan from 1932-53 – Ed.) prohibition on marrying a girl with three uncles who had been repressed could stop my father then. It was April 1941 after all, and my father was working on a strategic weapon. By the way, the guilt of my mother’s uncles was down to the fact that two of them had been sent to study abroad by the ADR government and the third had built a power plant in Lugano, Belgium.

My father often gave my mother flowers. As soon as violets bloomed, his favourite flowers, he came home at once with a bouquet of them for her. Memories of his childhood are connected with these flowers. Every spring violets blossom wildly on the mountains of Ordubad, the town where he was born. He told us how he and his peers had climbed these mountains and brought home armfuls of these flowers. Violets always reminded him of the town of his childhood and wild youth. On the title page of his doctoral dissertation for which he was awarded the Stalin Prize, the highest award of the time, he’d written: I dedicate this fruit of many years of labour to my darling.

My father often gave my mother flowers. As soon as violets bloomed, his favourite flowers, he came home at once with a bouquet of them for her

Often in the evenings, we watched as my mother played at the grand piano and sang my father’s favourite songs as he sat next to her. He was very fond of romances by Azerbaijani composers and Italian songs. When he was abroad he always brought back many records, such as the records of Andalusian folk music he brought back from a trip to Spain. He said that they reminded him very much of Azerbaijani mughams.

My father was an avid theatre-lover. He often took us with him to the opera, to the Azerbaijani and Russian drama theatres. Then we all discussed the performances, the acting, the directing. We children were pleased that he was interested in our opinion. He told us that he’d also acted in his youth in an amateur theatre in Ordubad.

He wrote: The most interesting thing in life is not the kaleidoscope of quickly changing events and external impressions, but a person’s inner world.

We used to walk along the boulevard on Sundays. But in truth we couldn’t get all his attention there because he was immediately surrounded by the most different people requesting things from him. He listened to everyone and always tried to help them.

It’s interesting that there was no taboo subject between us. He was always ready to listen to us and give advice. For example, we said that we didn’t like certain subjects at school because they weren’t interesting and he discussed these problems with us in detail.

He wrote: In life people have to do not only what they like but also things they don’t like. I don’t think that all students who study mathematics, physics, chemistry or other subjects do it because they love them. Are all the disciplines in higher education really to one’s liking? In this and many other cases in life the most important thing is human will and reason. I would really wish that reason and will play a crucial role in your actions in life.

Our Sunday walks usually ended with trips to the bookstore, which was housed in the Nizami Literature Museum. There he chose books not only for himself, but also for us, advising us to read more historical books, books that could benefit our education. He patiently explained to us how to leaf through books without damaging the pages. This careful treatment of books had developed since his childhood.

In the house in Ordubad books were always given pride of place. Having read all the books in the house, in the library, of close neighbours, my father found out that there was a person who lived in a village far from Ordubad who had a large library at home but didn’t let anyone borrow his books. My father went many kilometres to see him, and having promised to take great care of the books, was granted the opportunity to use his library. Every time he took one of his books, he carefully wrapped it in fabric in order not to spoil it on the way home. He read many books in his childhood and then managed to teach himself several languages. Being a great expert on Azerbaijani language and literature, he also spoke Russian, English, German and Farsi fluently.

We knew very well that my father loved books and that he could only punish us for treating them badly. By the way, he never raised his voice at us. Our most serious punishment was his disapproving look. I remember how one day he stopped my mother, who was about to tell me off for something I did wrong, and told her, It isn’t necessary. She will punish herself. We all knew the story about Brutus’ treachery well. And when my sister and I did something wrong, he half-joking, half-seriously said: and you, Brutus?

My father had a good sense of humour. There were moments of humour in the stories about his youth and also in his letters to us. He wrote: I received your sweet letter today. I thank you for the pleasure it gave me. I can have tea without sugar the whole week, the sweetness of your letter is enough for me. You see what a saving this is. But if you had written a really long letter, it would have been enough for jam too. As it happens now is the time for making jam.

You asked me to call on the weekends when you are at home. So I did, but unfortunately I didn’t catch you there. It turns out that you had gone to the school and solemnly taken an old iron there. I believe that your contribution to the collection of scrap metal will have an impact on the Central Statistical Office’s next report on metal smelting.

We often drove around the city in the car. He stopped at new buildings, watched the construction of the university buildings and the Academy, and was very happy with the scale of it. Sometimes we called in at the Botanical Garden, stopping at each tree and each ornamental plant, which he told us about with great inspiration and knowledge.

However his favourite brainchild was the observatory, whose construction in Shamakha began with great difficulty. His first attempt to build it began during his first spell as head of the Academy of Sciences (1947-1951). At that time the authorities in Moscow didn’t approve the project. Having become president of the Academy of Sciences for the second time, he managed to get permission and brought a telescope from Germany to Shamakha which was the biggest in Europe. By the way, the authorities tried to install this telescope at the Byurakan Observatory, but with great effort my father managed to bring it to Azerbaijan.

My father never allowed us to complain about something or someone. In response to the slightest desire to do this, he said: Be better than this! In childhood, I fell ill with scarlet fever. I remember that having heard my diagnosis, my mother started to cry and I thought I was dying. My father, having seen the fear in my eyes, said very firmly: You will definitely get well soon. And I promise that I will bring you a new toy every day until you get well. So for 40 days, which was how long I was isolated from other children, I received a new toy every day. How he managed to get them in those hard times I still can’t understand.

We decorated a Christmas tree with him every New Year. It was hard enough to buy a new toy in the 1950s, but there was a wonderful glass-blower working in his laboratory who made various glass bulbs and test tubes. At my father’s request, he blew some very beautiful glass toys for us and painted them in different colours. Our Christmas tree always looked very elegant.

His unusually sensitive attitude to people was well known. He gave money to people in need and often helped students and postgraduates. I’ve been told many different stories. For example, as rector of the university, he found out that a student he sent to study in Moscow couldn’t go because of financial difficulties. My father called the student and said he would send him money in Moscow every month, but that he absolutely must go and study there. Now this person is a great scientist himself and remembers his teacher with gratitude.

There is another story about a student studying in Moscow. Having seen him there in frosty weather in a thin jacket, my father told him: Help me choose some clothes for my son. He’s the same height as you. And they went together to the shop. Having chosen some warm clothes, my father gave them all to the student and in response to the student’s surprised look, he said: I don’t have a son. They’re for you. Your studying well in Moscow will show your gratitude to me.

Once one of his favourite students decided to get married but the girl’s parents didn’t let her marry him. Both of them were my father’s graduate students and the groom didn’t have a father. My father himself went to seek approval for the girl to marry his student. Of course, the girl’s parents couldn’t say no to such an eminent matchmaker and the marriage happened. And the student met my father’s expectations in every way, by becoming an associate member of the Academy of Sciences and a strong family man.

Nothing was dearer to him than Azerbaijan

My father often went on business trips to Moscow and stayed at the Moskva hotel where he always had his own room. And all the students and graduate students who were studying in Moscow knew that during those days a table would be laid for them and that they could request anything: a dorm room, money, a letter of support from him to those in charge of their diploma work, dissertations etc.

Legends have been told about his nobility and kindness. The academician Azad Mirzadjanzade wrote in his memories of him: If I were to come up with a unit of measure for kindness and nobility, I would call it 1 Y.M. after Yusuf Heydar oghlu Mammadaliyev.

Hasten to do good! These words that he often repeated became the motto of his life. His love for his country, for Azerbaijan, was boundless. All of his actions and deeds (too many for one article) were connected with this feeling. Our conversations with him, the stories and legends that he told us, always came down to this feeling. Nothing was dearer to him than Azerbaijan.

At his request, we never had curtains at home. He said that you shouldn’t curtain off the world around you. His office windows overlooked the sea. Standing there and looking at the Caspian for long periods is how I remember him most.

About the author: Sevda Mammadaliyeva PhD, Yusuf Mammadaliyev’s daughter, is Deputy Minister of Culture, a member of the Azerbaijani Academy of Sciences and several international academies. She is actively involved in UNESCO work and has represented Azerbaijan at the UN, ISESCO, TURKSOY, CIS, GUAM and Council of Europe in over 100 international symposia, conferences and forums.