Pages 44-52

by Farida Mamedova

The main cause of what is known as the "Karabagh problem" is the territorial claims of Armenians on Azerbaijanis and Azerbaijan. The Armenians’ constant attention towards Azerbaijan in general and Karabagh in particular has its roots in the complex history of the Armenian nation. This can be investigated through a short historical excursion. We’ll give a brief overview of the history of Artsakh-Karabagh, followed by some historical information about Armenia. [1]

by Farida Mamedova

The main cause of what is known as the "Karabagh problem" is the territorial claims of Armenians on Azerbaijanis and Azerbaijan. The Armenians’ constant attention towards Azerbaijan in general and Karabagh in particular has its roots in the complex history of the Armenian nation. This can be investigated through a short historical excursion. We’ll give a brief overview of the history of Artsakh-Karabagh, followed by some historical information about Armenia. [1]

Overview of Karabagh’s rulers

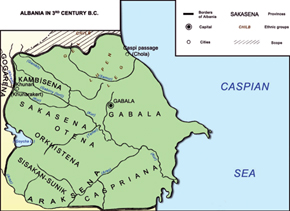

Part of what is now Mountainous Karabagh and part of the Mil plain formed the historical province of Karabagh-Artsakh, which was one of the most important provinces in Caucasian Albania, the earliest state in Northern Azerbaijan. It is known by different names - Orchsiten by ancient authors in the 1st century BC, Artsakh, then Khachen or Karabakh in early medieval and medieval Albanian, ancient Armenian, Byzantine, Arabian, ancient Georgian and Persian sources. Attempts to trace the etymology of the name on the basis of the Armenian language are not at all convincing. The toponyms of Artsakh and Uti can even be found in Spain in the Pyrenees. The word Artsakh occurs for the first time in the Avesta, the sacred scriptures of the Zoroastrians, with the meaning "country or territory of winds". The names Artsakh and Khachen occur in Albanian, Armenian and Byzantine sources of the 5th-17th centuries, while Karabagh is mentioned in Persian and Arabian sources of the 8th-14th centuries and in Georgian sources from the 12th century. Karabagh is a Turkic word meaning "large garden" or "black garden".

Karabagh-Artsakh has been an inseparable part of all the states that have existed on the territory of Northern Azerbaijan from ancient times to the present. Artsakh was part of the territory of Caucasian Albania from the 4th century BC to the 8th century AD. After the fall of Caucasian Albania Artsakh- Karabagh, as part of the geographical and political notion of "Azerbaijan", became part of the Azerbaijani Sajid state; in the 10th century it was part of the Salarid state; in the 11th-12th centuries part of the Shaddadid state [2]; in the 12th-13th centuries Karabagh became part of the Azerbaijani state of the Atabay-Eldenizids [3]; from the second half of the 13th century till the beginning of the 15th century, during the period of the Mongol Khulaguids, it became part of the Jalayarids’ state [4]; in the 15th century it was part of Karakoyunlu and then Ag-goyunlu states; and in the 16th-17th centuries Karabagh-Artsakh was part of the beylerbeyi of Karabagh in the Azerbaijani Safavid state. The Safavid state consisted of four beylerbeyis - Shirvan, Karabagh (or Ganja), Chukhursad (or Yerevan) and Azerbaijan (or Tabriz) [5]. The beylerbeyi of Karabagh was ruled by the Ziyadoglu family, who were from the Turkic Qajar tribe, from the 16th to the 19th centuries. [6]

In the second half of the 18th century Karabagh entered the Karabagh khanate. As part of the khanate it was annexed to Russia in 1805 and 1813 and finally after the Turkmenchay treaty in 1828. [7]

Karabakh has, therefore, never been part of any Armenian state or even administrative unit. The Armenian state was established in Asia Minor, well away from the South Caucasus.

The population of Karabagh in antiquity and the early and late Middle Ages were Caucasian-speaking Albanians, and from the 1st century AD were also Turkic-speaking tribes and Kurds, who kept increasing in number.

Part of what is now Mountainous Karabagh and part of the Mil plain formed the historical province of Karabagh-Artsakh, which was one of the most important provinces in Caucasian Albania, the earliest state in Northern Azerbaijan. It is known by different names - Orchsiten by ancient authors in the 1st century BC, Artsakh, then Khachen or Karabakh in early medieval and medieval Albanian, ancient Armenian, Byzantine, Arabian, ancient Georgian and Persian sources. Attempts to trace the etymology of the name on the basis of the Armenian language are not at all convincing. The toponyms of Artsakh and Uti can even be found in Spain in the Pyrenees. The word Artsakh occurs for the first time in the Avesta, the sacred scriptures of the Zoroastrians, with the meaning "country or territory of winds". The names Artsakh and Khachen occur in Albanian, Armenian and Byzantine sources of the 5th-17th centuries, while Karabagh is mentioned in Persian and Arabian sources of the 8th-14th centuries and in Georgian sources from the 12th century. Karabagh is a Turkic word meaning "large garden" or "black garden".

Karabagh-Artsakh has been an inseparable part of all the states that have existed on the territory of Northern Azerbaijan from ancient times to the present. Artsakh was part of the territory of Caucasian Albania from the 4th century BC to the 8th century AD. After the fall of Caucasian Albania Artsakh- Karabagh, as part of the geographical and political notion of "Azerbaijan", became part of the Azerbaijani Sajid state; in the 10th century it was part of the Salarid state; in the 11th-12th centuries part of the Shaddadid state [2]; in the 12th-13th centuries Karabagh became part of the Azerbaijani state of the Atabay-Eldenizids [3]; from the second half of the 13th century till the beginning of the 15th century, during the period of the Mongol Khulaguids, it became part of the Jalayarids’ state [4]; in the 15th century it was part of Karakoyunlu and then Ag-goyunlu states; and in the 16th-17th centuries Karabagh-Artsakh was part of the beylerbeyi of Karabagh in the Azerbaijani Safavid state. The Safavid state consisted of four beylerbeyis - Shirvan, Karabagh (or Ganja), Chukhursad (or Yerevan) and Azerbaijan (or Tabriz) [5]. The beylerbeyi of Karabagh was ruled by the Ziyadoglu family, who were from the Turkic Qajar tribe, from the 16th to the 19th centuries. [6]

In the second half of the 18th century Karabagh entered the Karabagh khanate. As part of the khanate it was annexed to Russia in 1805 and 1813 and finally after the Turkmenchay treaty in 1828. [7]

Karabakh has, therefore, never been part of any Armenian state or even administrative unit. The Armenian state was established in Asia Minor, well away from the South Caucasus.

The population of Karabagh in antiquity and the early and late Middle Ages were Caucasian-speaking Albanians, and from the 1st century AD were also Turkic-speaking tribes and Kurds, who kept increasing in number.

Armenians in the Balkans and Asia Minor

Now let’s look at the main milestones in the real history of the Armenian nation, of Armenian colonies spread over a large geographic area, and not the history of a stable state. All academic publications, dedicated to the problem, are known as the History of the Armenian Nation, although their authors try to describe absolutely incorrectly Armenian history as though it were the history of a stable state - Armenia. Armenia was soon exhausted as a political notion as it ceased to be a country, an expression meaning a political entity. Well-known Armenian expert K. Patponov, who translated Armenian sources from ancient Armenian into Russian, writes: "Armenia has never played a special role in the history of humanity. It is not a political notion, but the name of a geographical area, where the Armenian population lived. Armenians were always bad owners of the land where they lived, but always served the strong well, betraying those close to them." [8]

It is obvious that Armenians are native neither to Asia Minor (historical Turkey), nor the Caucasus. Armenian experts believe that Armenians from the Phrygian tribes previously lived in the Balkans and, taken up in the movement of the Cimmerians, appeared in Asia Minor in the 13th century BC. [9] Then they moved further east, to the Euphrates. According to the most recent edition of the History of the Armenian Nation groups of Indo- European Armenian tribes appeared on the territory of the Hurrites, Hetts and Luvians on the upper Euphrates in the 12th century BC. The tribes were called "Mushku" and "Urmu" in Assyrian cuneiform texts, "Arimams" in Greek, and then "Armenians". [10] Another famous Armenian expert and philologist, Manuk Abegyan, writes: "Where did the Armenian nation come from, when and how did they appear in Armenia, from where and via which routes did they come to their motherland, who influenced their language, ethnic structure and how? We do not have any exact and comprehensive information about all of this." [11] Armenians lived outside the Caucasus, in Asia Minor, the Armenian Plateau, around Lake Van and on the banks of the Euphrates and Tigris. The first Armenian state was founded on the territory of Asia Minor in the 6th century BC and existed until 428 AD. From the 6th to the 3rd century BC Armenia consisted of two satraps or provinces (Eastern Armenia and Western Armenia), which were first subject to the Persian Empire of the Achaemenids, then to Alexander the Great, and then to the Seleukid state.

The borders of the Armenian state were expanded in the 2nd and 1st century BC (during the reigns of Artashes I and Tigran II). Tigran II was defeated by the Roman commander Pompei and was stripped of all the land he had gained. Pompei allowed Tigran to retain the "kingdom he had inherited" [12] and later it is explained that this meant "primordial Armenian land, that is, the Armenian Plateau". Our research into the Armenian Plateau and Ararat Plain showed that the Armenian Plateau has no relation to the Caucasus.

As we noted above, from the 1st century BC to 428 Armenia was a nominal state in terms of its political status and in fact alternated between being a province of Persia and of Rome/Byzantium. Armenia was ruled by the appointees of Persia or Rome/Byzantium who could be either princes of Iberia or Atropotena. This means that the Armenian kings had no right of inheritance, i.e. they were nominal, not real rulers. In this period Armenia was divided several times between the two empires -Rome and Persia - in 66 BC and in 37, 298, 387, 591 AD and at other times. Under these divisions part of Armenia was included in Byzantium and was called Western Byzantine Armenia (west of the River Euphrates); this is Armenia Minor. Another part was included in Persia and called Eastern Persian Armenia (east of the River Euphrates) and this is Greater Armenia. Armenians started to share the history of the nations in the states, where they lived. [13] An Armenian Bagratid state was established in the 9th-11th centuries south of the upper and medial stretches of the Araz River, on the north shore of Lake Van. Then, according to Armenian historians, in the 12th-14th centuries the Armenian kingdom of Cilicia was established on the northeastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea. But my research shows that it is not right to consider Cilicia as an Armenian state.

The creators of the history of the Armenian nation, who in their works created the legendary concept of the alleged existence of two Albanias (Albania beyond the Kura and Albania between the Kura and Araz rivers), also tried for centuries and decades to present Albania between the Kura and Araz rivers as an eastern province of the "eternal" "Greater Armenia". Subsequently they managed to move the territory of the Armenian state in the 5th century and placed the Armenian Bagratid state geographically in the northwestern area of the South Caucasus. The Armenian state "simply" had to be merged with the central part of the Armenian Plateau in the east and then the Armenian Plateau was "moved" eastwards and set in the Ararat province-region. Thus, expanding the territory of the Ararat region to the (unusually created) "endless territory" of the Ararat county-region, Armenian historians achieved their desire - they merged the territory of the ancient, medieval Armenian states with the territory of the present Republic of Armenia, land in the eastern Caucasus, or to be more precise with the territory of historical Azerbaijani states. From the 9th to the 19th centuries the Armenians were deprived of their own state.

Now let’s look at the main milestones in the real history of the Armenian nation, of Armenian colonies spread over a large geographic area, and not the history of a stable state. All academic publications, dedicated to the problem, are known as the History of the Armenian Nation, although their authors try to describe absolutely incorrectly Armenian history as though it were the history of a stable state - Armenia. Armenia was soon exhausted as a political notion as it ceased to be a country, an expression meaning a political entity. Well-known Armenian expert K. Patponov, who translated Armenian sources from ancient Armenian into Russian, writes: "Armenia has never played a special role in the history of humanity. It is not a political notion, but the name of a geographical area, where the Armenian population lived. Armenians were always bad owners of the land where they lived, but always served the strong well, betraying those close to them." [8]

It is obvious that Armenians are native neither to Asia Minor (historical Turkey), nor the Caucasus. Armenian experts believe that Armenians from the Phrygian tribes previously lived in the Balkans and, taken up in the movement of the Cimmerians, appeared in Asia Minor in the 13th century BC. [9] Then they moved further east, to the Euphrates. According to the most recent edition of the History of the Armenian Nation groups of Indo- European Armenian tribes appeared on the territory of the Hurrites, Hetts and Luvians on the upper Euphrates in the 12th century BC. The tribes were called "Mushku" and "Urmu" in Assyrian cuneiform texts, "Arimams" in Greek, and then "Armenians". [10] Another famous Armenian expert and philologist, Manuk Abegyan, writes: "Where did the Armenian nation come from, when and how did they appear in Armenia, from where and via which routes did they come to their motherland, who influenced their language, ethnic structure and how? We do not have any exact and comprehensive information about all of this." [11] Armenians lived outside the Caucasus, in Asia Minor, the Armenian Plateau, around Lake Van and on the banks of the Euphrates and Tigris. The first Armenian state was founded on the territory of Asia Minor in the 6th century BC and existed until 428 AD. From the 6th to the 3rd century BC Armenia consisted of two satraps or provinces (Eastern Armenia and Western Armenia), which were first subject to the Persian Empire of the Achaemenids, then to Alexander the Great, and then to the Seleukid state.

The borders of the Armenian state were expanded in the 2nd and 1st century BC (during the reigns of Artashes I and Tigran II). Tigran II was defeated by the Roman commander Pompei and was stripped of all the land he had gained. Pompei allowed Tigran to retain the "kingdom he had inherited" [12] and later it is explained that this meant "primordial Armenian land, that is, the Armenian Plateau". Our research into the Armenian Plateau and Ararat Plain showed that the Armenian Plateau has no relation to the Caucasus.

As we noted above, from the 1st century BC to 428 Armenia was a nominal state in terms of its political status and in fact alternated between being a province of Persia and of Rome/Byzantium. Armenia was ruled by the appointees of Persia or Rome/Byzantium who could be either princes of Iberia or Atropotena. This means that the Armenian kings had no right of inheritance, i.e. they were nominal, not real rulers. In this period Armenia was divided several times between the two empires -Rome and Persia - in 66 BC and in 37, 298, 387, 591 AD and at other times. Under these divisions part of Armenia was included in Byzantium and was called Western Byzantine Armenia (west of the River Euphrates); this is Armenia Minor. Another part was included in Persia and called Eastern Persian Armenia (east of the River Euphrates) and this is Greater Armenia. Armenians started to share the history of the nations in the states, where they lived. [13] An Armenian Bagratid state was established in the 9th-11th centuries south of the upper and medial stretches of the Araz River, on the north shore of Lake Van. Then, according to Armenian historians, in the 12th-14th centuries the Armenian kingdom of Cilicia was established on the northeastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea. But my research shows that it is not right to consider Cilicia as an Armenian state.

The creators of the history of the Armenian nation, who in their works created the legendary concept of the alleged existence of two Albanias (Albania beyond the Kura and Albania between the Kura and Araz rivers), also tried for centuries and decades to present Albania between the Kura and Araz rivers as an eastern province of the "eternal" "Greater Armenia". Subsequently they managed to move the territory of the Armenian state in the 5th century and placed the Armenian Bagratid state geographically in the northwestern area of the South Caucasus. The Armenian state "simply" had to be merged with the central part of the Armenian Plateau in the east and then the Armenian Plateau was "moved" eastwards and set in the Ararat province-region. Thus, expanding the territory of the Ararat region to the (unusually created) "endless territory" of the Ararat county-region, Armenian historians achieved their desire - they merged the territory of the ancient, medieval Armenian states with the territory of the present Republic of Armenia, land in the eastern Caucasus, or to be more precise with the territory of historical Azerbaijani states. From the 9th to the 19th centuries the Armenians were deprived of their own state.

Key role of Church in Armenian history

Since the 15th century Armenians have closely linked their history to their Church, which gained in importance when the seat of the Catholicos was moved from Cilicia to Echmiadzin, near Yerevan, in 1441. And it is remarkable that this period in the history of the Armenian nation has become known as the special Echmiadzin period. Publications before the revolution, i.e. before 1918, recognised the name, but Soviet historians consigned it to oblivion. It is known that an ethnos can survive in the presence of territory, a state or a church. Armenians were deprived of the first and second so the Church began to fulfil the functions of the state. We have shown that the eparchyepiscopate of the Armenian Church, which was based in Echmiadzin, had been located on territory around Lake Van and on the banks of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers. Armenian feudal patrimonial groups with their domains were also located in this area. But, what links this Echmiadzin Church to the Caucasus? From the 15th century Echmiadzin led the political and other spheres of life of the Armenian nation as a reinforcing and organising authority for the diffuse Armenian nation. It also has to be noted that there was no unity in the Armenian Church with opposing seats in Constantinople and  The entrance of to the Museum of the history and culture of Caucasian Albania. Kish village, near Sheki Akhtamar in Lake Van.

The entrance of to the Museum of the history and culture of Caucasian Albania. Kish village, near Sheki Akhtamar in Lake Van.

In the 16th century Armenian clergy planned to purge the Caucasus of Caucasian Turks. And in the 16th-18th centuries Christian missionaries from Europe and America began to move to Asia Minor, where the mighty Ottoman Empire had already been created. The Armenians did not lose their ties with the Armenian Church (or to be more exact, acting on their instructions), simply embraced Catholicism or Lutheranism and studied at the missionaries’ schools. Missionaries fostered the first galaxy of the Armenian intelligentsia in Europe and America and laid the foundation of the future Armenian lobby, the future Armenian diaspora. These Armenians appropriated European rights quickly and easily, completely forgetting about responsibilities. Namely these Armenians, together with the Echmiadzin Church, became the ideologues of the settlement of Armenians in the historic Azerbaijani territories in the eastern Caucasus.

Since the 15th century Armenians have closely linked their history to their Church, which gained in importance when the seat of the Catholicos was moved from Cilicia to Echmiadzin, near Yerevan, in 1441. And it is remarkable that this period in the history of the Armenian nation has become known as the special Echmiadzin period. Publications before the revolution, i.e. before 1918, recognised the name, but Soviet historians consigned it to oblivion. It is known that an ethnos can survive in the presence of territory, a state or a church. Armenians were deprived of the first and second so the Church began to fulfil the functions of the state. We have shown that the eparchyepiscopate of the Armenian Church, which was based in Echmiadzin, had been located on territory around Lake Van and on the banks of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers. Armenian feudal patrimonial groups with their domains were also located in this area. But, what links this Echmiadzin Church to the Caucasus? From the 15th century Echmiadzin led the political and other spheres of life of the Armenian nation as a reinforcing and organising authority for the diffuse Armenian nation. It also has to be noted that there was no unity in the Armenian Church with opposing seats in Constantinople and

The entrance of to the Museum of the history and culture of Caucasian Albania. Kish village, near Sheki

The entrance of to the Museum of the history and culture of Caucasian Albania. Kish village, near Sheki In the 16th century Armenian clergy planned to purge the Caucasus of Caucasian Turks. And in the 16th-18th centuries Christian missionaries from Europe and America began to move to Asia Minor, where the mighty Ottoman Empire had already been created. The Armenians did not lose their ties with the Armenian Church (or to be more exact, acting on their instructions), simply embraced Catholicism or Lutheranism and studied at the missionaries’ schools. Missionaries fostered the first galaxy of the Armenian intelligentsia in Europe and America and laid the foundation of the future Armenian lobby, the future Armenian diaspora. These Armenians appropriated European rights quickly and easily, completely forgetting about responsibilities. Namely these Armenians, together with the Echmiadzin Church, became the ideologues of the settlement of Armenians in the historic Azerbaijani territories in the eastern Caucasus.

Concept of "Eastern Armenia" is born

With the arrival of the Ottoman Empire, the Armenians lost hope of creating their own state in the historical motherland in Asia Minor. Therefore, they turned their gaze to historical Azerbaijan, nurturing the idea of cleansing the Caucasus of Azerbaijani Turks. The creators of the History of the Armenian Nation brought into academic parlance the concept of "Eastern Armenia", which from the 15th to the 20th centuries refers exclusively to Azerbaijani territories: Karabagh, Yerevan, Ganja, Syunik-Zangezur. Thus, the concept of "Eastern Armenia" jumps both in time and place from east of the River Euphrates to the Caucasus. Why to the Caucasus? The Armenians who lived in the east - Persian Armenia - were actually located in Eastern Anatolia. Here Armenians were the neighbours of Kurds and also of the confederation of Turkic-speaking tribes in the 14th-15th centuries – Karakoyunlu and Ag-koyunlu. The Armenians saw these peoples found their states in the southeastern Caucasus: in the 10th-11th centuries Kurds founded the Nakhchivan-Arran Emirate, a Shaddadid state, and the confederation of Turkic tribes founded Kara-koyunlu and Ag-koyunlu states south of the River Kura. It had been possible to create these states as the ethnic environment in the area had already been prepared for the establishment of states. In the 9th-11th centuries the Kurds were already brought together between the Kura and Araz rivers. And the Turkic-speaking tribes were ethnically dominant in this area. The presence in the Caucasus of local states, not empires, should also be taken into account in creating the opportunity for the formation of new states.

This allowed Armenian historians finally to join Azerbaijani territory, where the remnants of the Albanians lived - Artsakh and Syunik - some of whose population were Christians (the Albanians had not lost their territorial and political unity) and maintained confessional unity with the Armenians (monophysitism) and Copts. But the Armenians could achieve their goals only with the help of the European powers and especially of Russia. Armenian historians tell the history of the Azerbaijani beylerbeys (regions) of Karabagh, Ganja, Yerevan and Nakhchivan, which later became khanates under the title the History of the Armenian Nation in the 16th, 17th, 18th and 19th centuries.

From the 18th century Armenians entered Russia through Poland (?!). They tried to interest the Russian court and Peter I in the importance of the liberation of so-called "Eastern Armenia" from the Turkish and Persian yoke, but actually they held negotiations on the liberation of Karabagh, Yerevan, Zangezur and Nakhchivan, where the remnants of the Christian Albanian population lived alongside Turks and Kurds.

In Armenian publications the Albanian Karabagh meliks in the 15th to 18th centuries are without any foundation described as Armenian and everything that happened to them is included in Armenian history.

Special chapters on the history of the Armenian nation in the 17th-18th centuries have the titles Armenian- Russian relations, Israel Ori and Independence movement in 1720. These do not deal with Armenian history in the 18th century, but with the Albanian Christian population that lived in the Karabagh melikate and with their independence movement.

In the same way Armenian historians distort the independence movement of the Karabagh and Zangezur melikates, which was led by David bek in 1722-1728. It is very interesting that there is nothing in the "histories" of the Armenian nation about Potemkin’s project, which is related to the foundation of the Albanian kingdom. The history does say: "In order to win over the Christian population of the Trans- Caucasus to their side the Tsarist government promoted the view that the aim of the Russian troops was the ’restoration of Armenia’." [14] But the last edition of the History of the Armenian Nation (1980) talks about negotiations between the Armenian eparchy in Russia and representatives of the Russian government which reportedly envisaged the liberation of Armenia by Commander A.V. Suvorov and the restoration of the Armenian state with its capital in Yerevan. "The proposal was made to create a special Armenian regiment together with troops of the Armenian meliks of Karabagh, which would liberate Ararat province, and then the remaining Armenian areas." [?!] [15]

Talking about the 18th century the History of the Armenian Nation (1980) says: "West Armenia was divided... into Erzurum, Kars ...Diyarbekir. In East Armenia and Azerbaijan the khanates of Yerevan, Nakhchivan, Karabagh, Shirvan etc. were founded." We can see that all the khanates were Azerbaijani.The "histories" of the Armenian nation say nothing about the Azerbaijani beylerbeyi that existed before the khanates. Yerevan and Nakhchivan were settlements (ulka) of the Ustajlu Kizilbash tribes. Chukhur-Saad remained as their inherited ulka. It is clear that there was no Eastern Armenia on these territories. It should be noted especially that the Karabagh beylerbeyi consisted of a large territory between the Kura and Araz rivers, including Kazakh, Shamshadil, Lori and Pambak. [16] When the Azerbaijani khanates were established, the Karabagh beylerbeyi became a khanate.

As for the Armenian ethnos, the History of the Armenian Nation (1980, page 187) contains the requisite acknowledgement: "In the beginning of the 20th century an important part of the Armenian nation lived outside their motherland - in neighbouring and distant countries... A great number of Armenians did not lose touch with their motherland. [?!-F.M.] The question naturally arises: what does the term "their motherland" imply, where is it?! With what area did the Armenian colonies keep in constant touch?! Following Armenian history carefully through the centuries, reading the works of Armenian historians, we could not find the Armenian motherland - a politically unified, permanent stable territory. A common territory, where the nation is founded and formed, is the basic measure of an ethnos or nation. The Armenians have to define this common territory and then create a real history, and not latch on to new areas every time, either Azerbaijani regions - Karabagh, Syunik Zangezur and other territories - or southern Georgia (Gogeran), as they did in the early 20th century, which I. Chavchavadze and V.L. Velichko wrote about. The latter noted that in Armenian maps the territory of "Greater Armenia" goes almost as far as Voronezh, with its capital in Tbilisi. He also wrote: "They (Armenians) steal from Georgian history and architecture quite shamelessly; they rub Georgian inscriptions from monuments..., they make up historical nonsense and refer as Armenian possessions to areas where every stone talks about the past of the Georgian kingdom." [17] The public prosecutor of the Echmiadzin Synod, A. Frenkel, wrote about this at the beginning of the century: "The historical fate of the Armenian nation has proved incontrovertibly the complete inability of this nation to create their own independent state, state organism." [18] Without the help of Russia and foreign countries Armenians would never have acquired statehood.

With the arrival of the Ottoman Empire, the Armenians lost hope of creating their own state in the historical motherland in Asia Minor. Therefore, they turned their gaze to historical Azerbaijan, nurturing the idea of cleansing the Caucasus of Azerbaijani Turks. The creators of the History of the Armenian Nation brought into academic parlance the concept of "Eastern Armenia", which from the 15th to the 20th centuries refers exclusively to Azerbaijani territories: Karabagh, Yerevan, Ganja, Syunik-Zangezur. Thus, the concept of "Eastern Armenia" jumps both in time and place from east of the River Euphrates to the Caucasus. Why to the Caucasus? The Armenians who lived in the east - Persian Armenia - were actually located in Eastern Anatolia. Here Armenians were the neighbours of Kurds and also of the confederation of Turkic-speaking tribes in the 14th-15th centuries – Karakoyunlu and Ag-koyunlu. The Armenians saw these peoples found their states in the southeastern Caucasus: in the 10th-11th centuries Kurds founded the Nakhchivan-Arran Emirate, a Shaddadid state, and the confederation of Turkic tribes founded Kara-koyunlu and Ag-koyunlu states south of the River Kura. It had been possible to create these states as the ethnic environment in the area had already been prepared for the establishment of states. In the 9th-11th centuries the Kurds were already brought together between the Kura and Araz rivers. And the Turkic-speaking tribes were ethnically dominant in this area. The presence in the Caucasus of local states, not empires, should also be taken into account in creating the opportunity for the formation of new states.

This allowed Armenian historians finally to join Azerbaijani territory, where the remnants of the Albanians lived - Artsakh and Syunik - some of whose population were Christians (the Albanians had not lost their territorial and political unity) and maintained confessional unity with the Armenians (monophysitism) and Copts. But the Armenians could achieve their goals only with the help of the European powers and especially of Russia. Armenian historians tell the history of the Azerbaijani beylerbeys (regions) of Karabagh, Ganja, Yerevan and Nakhchivan, which later became khanates under the title the History of the Armenian Nation in the 16th, 17th, 18th and 19th centuries.

From the 18th century Armenians entered Russia through Poland (?!). They tried to interest the Russian court and Peter I in the importance of the liberation of so-called "Eastern Armenia" from the Turkish and Persian yoke, but actually they held negotiations on the liberation of Karabagh, Yerevan, Zangezur and Nakhchivan, where the remnants of the Christian Albanian population lived alongside Turks and Kurds.

In Armenian publications the Albanian Karabagh meliks in the 15th to 18th centuries are without any foundation described as Armenian and everything that happened to them is included in Armenian history.

Special chapters on the history of the Armenian nation in the 17th-18th centuries have the titles Armenian- Russian relations, Israel Ori and Independence movement in 1720. These do not deal with Armenian history in the 18th century, but with the Albanian Christian population that lived in the Karabagh melikate and with their independence movement.

In the same way Armenian historians distort the independence movement of the Karabagh and Zangezur melikates, which was led by David bek in 1722-1728. It is very interesting that there is nothing in the "histories" of the Armenian nation about Potemkin’s project, which is related to the foundation of the Albanian kingdom. The history does say: "In order to win over the Christian population of the Trans- Caucasus to their side the Tsarist government promoted the view that the aim of the Russian troops was the ’restoration of Armenia’." [14] But the last edition of the History of the Armenian Nation (1980) talks about negotiations between the Armenian eparchy in Russia and representatives of the Russian government which reportedly envisaged the liberation of Armenia by Commander A.V. Suvorov and the restoration of the Armenian state with its capital in Yerevan. "The proposal was made to create a special Armenian regiment together with troops of the Armenian meliks of Karabagh, which would liberate Ararat province, and then the remaining Armenian areas." [?!] [15]

Talking about the 18th century the History of the Armenian Nation (1980) says: "West Armenia was divided... into Erzurum, Kars ...Diyarbekir. In East Armenia and Azerbaijan the khanates of Yerevan, Nakhchivan, Karabagh, Shirvan etc. were founded." We can see that all the khanates were Azerbaijani.The "histories" of the Armenian nation say nothing about the Azerbaijani beylerbeyi that existed before the khanates. Yerevan and Nakhchivan were settlements (ulka) of the Ustajlu Kizilbash tribes. Chukhur-Saad remained as their inherited ulka. It is clear that there was no Eastern Armenia on these territories. It should be noted especially that the Karabagh beylerbeyi consisted of a large territory between the Kura and Araz rivers, including Kazakh, Shamshadil, Lori and Pambak. [16] When the Azerbaijani khanates were established, the Karabagh beylerbeyi became a khanate.

As for the Armenian ethnos, the History of the Armenian Nation (1980, page 187) contains the requisite acknowledgement: "In the beginning of the 20th century an important part of the Armenian nation lived outside their motherland - in neighbouring and distant countries... A great number of Armenians did not lose touch with their motherland. [?!-F.M.] The question naturally arises: what does the term "their motherland" imply, where is it?! With what area did the Armenian colonies keep in constant touch?! Following Armenian history carefully through the centuries, reading the works of Armenian historians, we could not find the Armenian motherland - a politically unified, permanent stable territory. A common territory, where the nation is founded and formed, is the basic measure of an ethnos or nation. The Armenians have to define this common territory and then create a real history, and not latch on to new areas every time, either Azerbaijani regions - Karabagh, Syunik Zangezur and other territories - or southern Georgia (Gogeran), as they did in the early 20th century, which I. Chavchavadze and V.L. Velichko wrote about. The latter noted that in Armenian maps the territory of "Greater Armenia" goes almost as far as Voronezh, with its capital in Tbilisi. He also wrote: "They (Armenians) steal from Georgian history and architecture quite shamelessly; they rub Georgian inscriptions from monuments..., they make up historical nonsense and refer as Armenian possessions to areas where every stone talks about the past of the Georgian kingdom." [17] The public prosecutor of the Echmiadzin Synod, A. Frenkel, wrote about this at the beginning of the century: "The historical fate of the Armenian nation has proved incontrovertibly the complete inability of this nation to create their own independent state, state organism." [18] Without the help of Russia and foreign countries Armenians would never have acquired statehood.

Russia increases role in Armenian history

Russia conquered the Caucasus by the 1850s and strengthened its positions there: it liquidated the ethnopolitical formations of the native population - the Georgian kingdom and Azerbaijani khanates (in particular Karabagh) - and for the first time founded a political entity that had never existed in the Caucasus, an Armenian region in the Azerbaijani khanates of Yerevan and Nakhchivan. Russia first increased the number of Armenians in these areas (and in Karabagh) by resettling Armenians from the Ottoman Empire and Albanians from Persia. Tsarist Russia weakened the two ancient autocephalous apostolic churches in the Caucasus, the Georgian and Albanian churches, which had functioned from the 4th to the 19th centuries. Russia deprived the Georgian Church of its autocephalous status and abolished the Albanian Church, turning it into an eparchy of the Echmiadzin Armenian Church, depriving the native Albanian population of their ethnicity.

Having strongly reinforced the political, ideological and economic position of the Echmiadzin Church in the Caucasus, as the geopolitical situation changed, Russia started to fear separatist trends in the strong Armenian Echmiadzin Church and the pressure of the Armenian diaspora, methodically seeking statehood in the Caucasus. Therefore, in 1850 Tsarist Russia abolished the Armenian region and turned it into the Yerevan Province. Probably the subsequent policy of the Russian Empire no longer envisaged the establishment of an Armenian state in the Caucasus, (which enabled Russia to keep the Armenians in its full and constant grip) but planned to use the Armenians as a "satellite-factor" in its Middle East policy.

In the 1860s Tsarist Russia nurtured the idea of establishing an Armenian region - Western Armenia - in Turkish land in Asia Minor. Tsarist Russia disguised its efforts to occupy the Black Sea, Bosporus and Dardanelles under the rallying cry of "the struggle to free Christians and Armenians from the yoke of Muslim Turkey".

The issue of Western Armenia and the situation of the Armenian population in Turkey began to be called the "Armenian question" in the negotiations in San Stefano and Berlin in 1878. According to this, Turkey should make the necessary reforms in the Armenian vilayets. It was practically only Russia that supported resolution of the "Armenian question". The political parties “Hnchak" (1887) and “Dashnaksyutun” (1890) were established with this aim. Based in the Russian Caucasus they sent propagandists to Turkey and organized rebel groups, who aimed first of all to attract the attention of the great powers. In order to achieve its goals the Dashnaksyutun party often changed the direction of its policy from Russia to the European countries, to the panTurkist revolutionary movement, to the Young Turks and back again to Russia. According to Milyukov, the Armenians, "planting themselves at the crossroads between Russia and Turkey" had gained major political significance on the eve of World War I. [19] During the Balkan war (1912-1914) Russia proposed a plan to create an autonomous Armenian region in Turkey, so-called Western Armenia, from the vilayets of Erzurum, Van, Bitlis, Diyarbekir, Kharput and Civas. The governor of Western Armenia would have to be a Christian, appointed by Turkey but with the agreement of the European states. But the European states did not support this proposal. [20] The "genocide" of Armenians in 1915 in Turkey was timely for the Armenians, accelerating the issue of the establishment of an Armenian state [21], but this time in a different territory.

The Armenians skilfully used every revolution to attain their aims. The February and October revolutions in 1917 speeded up the resolution of the Armenian question. An Armenian national congress gathered in Tbilisi in October 1917 and demanded on behalf of the whole Armenian nation that Turkish Armenia, occupied by Russian troops during World War I, should remain in Russia. Lenin also supported the idea of establishing Western Armenia and signed a decree on 28 October 1917 according to which Soviet Russia pronounced the right to self-determination of so-called Western Armenia [22].

Russia conquered the Caucasus by the 1850s and strengthened its positions there: it liquidated the ethnopolitical formations of the native population - the Georgian kingdom and Azerbaijani khanates (in particular Karabagh) - and for the first time founded a political entity that had never existed in the Caucasus, an Armenian region in the Azerbaijani khanates of Yerevan and Nakhchivan. Russia first increased the number of Armenians in these areas (and in Karabagh) by resettling Armenians from the Ottoman Empire and Albanians from Persia. Tsarist Russia weakened the two ancient autocephalous apostolic churches in the Caucasus, the Georgian and Albanian churches, which had functioned from the 4th to the 19th centuries. Russia deprived the Georgian Church of its autocephalous status and abolished the Albanian Church, turning it into an eparchy of the Echmiadzin Armenian Church, depriving the native Albanian population of their ethnicity.

Having strongly reinforced the political, ideological and economic position of the Echmiadzin Church in the Caucasus, as the geopolitical situation changed, Russia started to fear separatist trends in the strong Armenian Echmiadzin Church and the pressure of the Armenian diaspora, methodically seeking statehood in the Caucasus. Therefore, in 1850 Tsarist Russia abolished the Armenian region and turned it into the Yerevan Province. Probably the subsequent policy of the Russian Empire no longer envisaged the establishment of an Armenian state in the Caucasus, (which enabled Russia to keep the Armenians in its full and constant grip) but planned to use the Armenians as a "satellite-factor" in its Middle East policy.

In the 1860s Tsarist Russia nurtured the idea of establishing an Armenian region - Western Armenia - in Turkish land in Asia Minor. Tsarist Russia disguised its efforts to occupy the Black Sea, Bosporus and Dardanelles under the rallying cry of "the struggle to free Christians and Armenians from the yoke of Muslim Turkey".

The issue of Western Armenia and the situation of the Armenian population in Turkey began to be called the "Armenian question" in the negotiations in San Stefano and Berlin in 1878. According to this, Turkey should make the necessary reforms in the Armenian vilayets. It was practically only Russia that supported resolution of the "Armenian question". The political parties “Hnchak" (1887) and “Dashnaksyutun” (1890) were established with this aim. Based in the Russian Caucasus they sent propagandists to Turkey and organized rebel groups, who aimed first of all to attract the attention of the great powers. In order to achieve its goals the Dashnaksyutun party often changed the direction of its policy from Russia to the European countries, to the panTurkist revolutionary movement, to the Young Turks and back again to Russia. According to Milyukov, the Armenians, "planting themselves at the crossroads between Russia and Turkey" had gained major political significance on the eve of World War I. [19] During the Balkan war (1912-1914) Russia proposed a plan to create an autonomous Armenian region in Turkey, so-called Western Armenia, from the vilayets of Erzurum, Van, Bitlis, Diyarbekir, Kharput and Civas. The governor of Western Armenia would have to be a Christian, appointed by Turkey but with the agreement of the European states. But the European states did not support this proposal. [20] The "genocide" of Armenians in 1915 in Turkey was timely for the Armenians, accelerating the issue of the establishment of an Armenian state [21], but this time in a different territory.

The Armenians skilfully used every revolution to attain their aims. The February and October revolutions in 1917 speeded up the resolution of the Armenian question. An Armenian national congress gathered in Tbilisi in October 1917 and demanded on behalf of the whole Armenian nation that Turkish Armenia, occupied by Russian troops during World War I, should remain in Russia. Lenin also supported the idea of establishing Western Armenia and signed a decree on 28 October 1917 according to which Soviet Russia pronounced the right to self-determination of so-called Western Armenia [22].

Armenian Republic declared

In May 1918 when the Trans-Caucasus Seim collapsed, the Armenian independent republic was declared, although it had neither land nor a capital city. The declaration was made in Tbilisi. On 29 May 1918 the ADR (Azerbaijan Democratic Republic) ceded Yerevan to the Republic of Armenia. [23] The territory of the Republic of Armenia consisted almost only of Yerevan and Echmiadzin districts with a population of 400,000.

At the end of World War I the powers saw Armenia as a buffer against Turkey in Cilicia and against Soviet Russia in the Trans-Caucasus. The entente gave the region of Kars and districts of the Yerevan governorate to the Republic of Armenia.

The population of this republic was 1.5 million in 1918, 700,000 of whom were Armenians. But, not content with this, the Dashnaks laid claim to Akhalkalaki and Borchali in Georgia and also to Karabagh, Nakhchivan and Zangezur in Azerbaijan. These claims led to war with Georgia and to a long and bloody war with Azerbaijan. The Republic of Armenia used brute force to annex Azerbaijani territories illegally. [24] On 12 August 1918 Lenin signed a decree handing over Nakhchivan and Zangezur to the Dashnaks. In summer 1918 Gen Andranik invaded Zangezur with an Armenian army and gave the people an ultimatum - either submit to their rule or leave the settlements. According to Mikhaylov’s investigation commission, in  The general view of the Khamshivank monastery complex, X-XIII centuries, Beyuk Kara Murad village, Gederbek district summer 1918 alone, 115 Azerbaijani villages were destroyed, 7,000 people were killed and 50,000 Azerbaijanis had to leave Zangezur. [25] The struggle was especially fierce in Karabagh.

The general view of the Khamshivank monastery complex, X-XIII centuries, Beyuk Kara Murad village, Gederbek district summer 1918 alone, 115 Azerbaijani villages were destroyed, 7,000 people were killed and 50,000 Azerbaijanis had to leave Zangezur. [25] The struggle was especially fierce in Karabagh.

In 1919-1920 the European countries were no longer interested in the Armenian question, i.e. in the establishment of Armenia. The Armenia question was given to North America. The General Council of the League of Nations accepted that Armenia could not exist "without support". [26]

US President Wilson accepted the charge of the League of Nations to determine the boundaries of Armenia. But American politicians rejected the "mandate on Armenia", as they thought that the Armenian question was a European issue and the majority in the Senate rejected it. [27]

The government of France did exactly the same with the Armenians in Cilicia, which was occupied in 1919. In 1921 France signed a peace treaty with Turkey and gave up Cilicia. The Armenians were defeated and some were killed. The pitiful remnants of the Armenians went to Syria, Cyprus and Egypt. [28]

In this way one of the two "Armenian bases" was liquidated. The Armenian question centred in the Trans-Caucasus, where the Dashnaks conducted a policy of militant nationalism.

In March-July 1920 clashes occurred with the Dashnaks in the districts of Karabagh, Shusha, Nakhchivan, Ordubad, Terter, Askeran, Zangezur, Jebrail and Ganja. Dozens of Azerbaijani villages were destroyed.

Soviet Russia decided not to allow the Republic of Armenia to turn into an anti-Soviet bridgehead and became a mediator in resolving territorial problems between Azerbaijan and Armenia. Having got arms from Great Britain and Italy, the Dashnaks carried out pogroms of Muslim Turks in Karabagh, Nakhchivan and Zangezur and in the Yerevan and Kars governorates. In October 1920 Kara Bekir’s and Khalil Pasha’s Eastern Turkish Army took Kars and Alexandropol and made the Armenians sign what was for them the latest shameful peace treaty. The Dashnaks twice asked the governments of the USA, Great Britain, France and Italy for help, but they were refused. [29] In November 1920 the Dashnak government was overthrown and Soviet rule established. The Dashnaks remained in Zangezur and established "the Government of Syunik" in December 1920 (the Armenian Mountainous Republic). It was not until June-July 1921 that Zangezur was liberated from the Dashnaks. [30]

The Russian-Turkish treaty of 1921 annulled the Alexandropol peace treaty and set the current borders between Turkey and Armenia. From this time the Armenians began life as a state in the Caucasus. After the fall of the Republic of Azerbaijan, Soviet Russia reviewed its position once more. Realising the nonsense of the idea of establishing Western Armenia in Turkey it decided to create so-called Eastern Armenia from Azerbaijani territories - the former Yerevan khanate and Zangezur where at that time there were already compact Armenian settlements. After Soviet rule was established in Azerbaijan in April 1920, Nariman Narimanov insisted several times that Mountainous Karabagh, Zangezur and Nakhchivan should be united with Azerbaijan. He said: "Nobody can stop us influencing the population of these regions so that they insist on uniting with Azerbaijan." [31] "Ceding these regions to Armenia discredits Soviet rule not only in Azerbaijan, but also in Persia and Turkey." [32] The Soviet government tried to resolve the Armenian question at the expense of Azerbaijani territories, establishing Eastern Armenia. Azerbaijani territories were practically used as ransom to realise the idea of establishing the Soviet Republic of Armenia.

On 16 March 1921 the agreement signed between Kemalist Turkey and Soviet Russia set the legal bases for the establishment of the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic in Azerbaijan.

Article 3 of the agreement says: "The Nakhchivan region, within the boundaries defined in appendix 1(c) to the current agreement forms an autonomous territory under the protectorate of Azerbaijan on condition that Azerbaijan will never cede said protectorate to a third state." [33] Soon Nariman Narimanov expressed the will of the Azerbaijani people and demanded categorically that Karabagh remain within Azerbaijan. He said that otherwise "the Soviet National Committee will bear responsibility", as "we will re-establish ... an anti-Soviet group in Azerbaijan." [34] On the basis of this statement on 5 July 1921 a sitting of the Caucasus Bureau decided to leave Mountainous Karabagh within the borders of the Azerbaijani SSR, giving it broad autonomy and creating an autonomous region within Azerbaijan. [35]

So the Republic of Armenia was established in 1920 in the Yerevan governorate on Azerbaijani territories (the former Azerbaijani Yerevan khanate). In 1921 Zangezur district was also taken from Azerbaijan and given to the newly established Armenian SSR. In 1922 when the USSR was being created, the Azerbaijani territories of Dilijan and Gokche (Sharur-Daralayaz district) were joined to the Armenian SSR. In 1923 the NKAO (Mountainous Karabagh Autonomous Region) was established on the territory of the Azerbaijani SSR. In 1929 several villages were separated from Nakhchivan and joined the Armenian SSR. And in 1969 the Republic of Armenia increased its territory at the expense of Azerbaijani villages in Kazakh and Sadarak regions.

Well-known orientalist I.P. Petrushevski wrote quite justifiably: "Karabagh has never been a centre of Armenian culture." [36]

It should not be forgotten that the Karabagh problem is unique in history.

About the author: Farida Mamedova is a corresponding member of the Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan and chairman of the Executive Committee of the Caucasus Albania Research Centre.

Footnotes

In May 1918 when the Trans-Caucasus Seim collapsed, the Armenian independent republic was declared, although it had neither land nor a capital city. The declaration was made in Tbilisi. On 29 May 1918 the ADR (Azerbaijan Democratic Republic) ceded Yerevan to the Republic of Armenia. [23] The territory of the Republic of Armenia consisted almost only of Yerevan and Echmiadzin districts with a population of 400,000.

At the end of World War I the powers saw Armenia as a buffer against Turkey in Cilicia and against Soviet Russia in the Trans-Caucasus. The entente gave the region of Kars and districts of the Yerevan governorate to the Republic of Armenia.

The population of this republic was 1.5 million in 1918, 700,000 of whom were Armenians. But, not content with this, the Dashnaks laid claim to Akhalkalaki and Borchali in Georgia and also to Karabagh, Nakhchivan and Zangezur in Azerbaijan. These claims led to war with Georgia and to a long and bloody war with Azerbaijan. The Republic of Armenia used brute force to annex Azerbaijani territories illegally. [24] On 12 August 1918 Lenin signed a decree handing over Nakhchivan and Zangezur to the Dashnaks. In summer 1918 Gen Andranik invaded Zangezur with an Armenian army and gave the people an ultimatum - either submit to their rule or leave the settlements. According to Mikhaylov’s investigation commission, in

The general view of the Khamshivank monastery complex, X-XIII centuries, Beyuk Kara Murad village, Gederbek district

The general view of the Khamshivank monastery complex, X-XIII centuries, Beyuk Kara Murad village, Gederbek district In 1919-1920 the European countries were no longer interested in the Armenian question, i.e. in the establishment of Armenia. The Armenia question was given to North America. The General Council of the League of Nations accepted that Armenia could not exist "without support". [26]

US President Wilson accepted the charge of the League of Nations to determine the boundaries of Armenia. But American politicians rejected the "mandate on Armenia", as they thought that the Armenian question was a European issue and the majority in the Senate rejected it. [27]

The government of France did exactly the same with the Armenians in Cilicia, which was occupied in 1919. In 1921 France signed a peace treaty with Turkey and gave up Cilicia. The Armenians were defeated and some were killed. The pitiful remnants of the Armenians went to Syria, Cyprus and Egypt. [28]

In this way one of the two "Armenian bases" was liquidated. The Armenian question centred in the Trans-Caucasus, where the Dashnaks conducted a policy of militant nationalism.

In March-July 1920 clashes occurred with the Dashnaks in the districts of Karabagh, Shusha, Nakhchivan, Ordubad, Terter, Askeran, Zangezur, Jebrail and Ganja. Dozens of Azerbaijani villages were destroyed.

Soviet Russia decided not to allow the Republic of Armenia to turn into an anti-Soviet bridgehead and became a mediator in resolving territorial problems between Azerbaijan and Armenia. Having got arms from Great Britain and Italy, the Dashnaks carried out pogroms of Muslim Turks in Karabagh, Nakhchivan and Zangezur and in the Yerevan and Kars governorates. In October 1920 Kara Bekir’s and Khalil Pasha’s Eastern Turkish Army took Kars and Alexandropol and made the Armenians sign what was for them the latest shameful peace treaty. The Dashnaks twice asked the governments of the USA, Great Britain, France and Italy for help, but they were refused. [29] In November 1920 the Dashnak government was overthrown and Soviet rule established. The Dashnaks remained in Zangezur and established "the Government of Syunik" in December 1920 (the Armenian Mountainous Republic). It was not until June-July 1921 that Zangezur was liberated from the Dashnaks. [30]

The Russian-Turkish treaty of 1921 annulled the Alexandropol peace treaty and set the current borders between Turkey and Armenia. From this time the Armenians began life as a state in the Caucasus. After the fall of the Republic of Azerbaijan, Soviet Russia reviewed its position once more. Realising the nonsense of the idea of establishing Western Armenia in Turkey it decided to create so-called Eastern Armenia from Azerbaijani territories - the former Yerevan khanate and Zangezur where at that time there were already compact Armenian settlements. After Soviet rule was established in Azerbaijan in April 1920, Nariman Narimanov insisted several times that Mountainous Karabagh, Zangezur and Nakhchivan should be united with Azerbaijan. He said: "Nobody can stop us influencing the population of these regions so that they insist on uniting with Azerbaijan." [31] "Ceding these regions to Armenia discredits Soviet rule not only in Azerbaijan, but also in Persia and Turkey." [32] The Soviet government tried to resolve the Armenian question at the expense of Azerbaijani territories, establishing Eastern Armenia. Azerbaijani territories were practically used as ransom to realise the idea of establishing the Soviet Republic of Armenia.

On 16 March 1921 the agreement signed between Kemalist Turkey and Soviet Russia set the legal bases for the establishment of the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic in Azerbaijan.

Article 3 of the agreement says: "The Nakhchivan region, within the boundaries defined in appendix 1(c) to the current agreement forms an autonomous territory under the protectorate of Azerbaijan on condition that Azerbaijan will never cede said protectorate to a third state." [33] Soon Nariman Narimanov expressed the will of the Azerbaijani people and demanded categorically that Karabagh remain within Azerbaijan. He said that otherwise "the Soviet National Committee will bear responsibility", as "we will re-establish ... an anti-Soviet group in Azerbaijan." [34] On the basis of this statement on 5 July 1921 a sitting of the Caucasus Bureau decided to leave Mountainous Karabagh within the borders of the Azerbaijani SSR, giving it broad autonomy and creating an autonomous region within Azerbaijan. [35]

So the Republic of Armenia was established in 1920 in the Yerevan governorate on Azerbaijani territories (the former Azerbaijani Yerevan khanate). In 1921 Zangezur district was also taken from Azerbaijan and given to the newly established Armenian SSR. In 1922 when the USSR was being created, the Azerbaijani territories of Dilijan and Gokche (Sharur-Daralayaz district) were joined to the Armenian SSR. In 1923 the NKAO (Mountainous Karabagh Autonomous Region) was established on the territory of the Azerbaijani SSR. In 1929 several villages were separated from Nakhchivan and joined the Armenian SSR. And in 1969 the Republic of Armenia increased its territory at the expense of Azerbaijani villages in Kazakh and Sadarak regions.

Well-known orientalist I.P. Petrushevski wrote quite justifiably: "Karabagh has never been a centre of Armenian culture." [36]

It should not be forgotten that the Karabagh problem is unique in history.

About the author: Farida Mamedova is a corresponding member of the Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan and chairman of the Executive Committee of the Caucasus Albania Research Centre.

Footnotes

1. Mamedova, Farida Ursahen und Folgen des Karabach-Problems.Eine historische Untersuchung. Baden-Baden, Band 2, 1995, pp. 110-128

2. Sharifli, M.Kh Feodalniye gosudarstva Azerbaijana vo vtoroy polovine X-XI vekhakh, Baku, 1978, pp. 30-89, 344

3. Buniatov, Z.M. Gosudarstva atabekov Azerbaijana, Baku, 1978

4. Piriyev, V.Z. Ob istoricheskoy geografii Azerbaijana, Baku, 1987 pp. 98-105

5. Efendiyev, O. Azerbaijanskoye gosudarstvo Sefevidov v XVI veke, Baku 1981

6. Efendiyev, O. Territoriya i granitsi azerbaijanskikh gosudarstv v XV-XVI vekakh, see also the collection Istoricheskaya geografyiya Azerbaijana p. 114

7. O Karabakhe v sostave azerbaijanskikh gosudarstv, see also the collection Istoricheskaya geografiya Azerbaijana

8. Patkanov, K. Vanskiye nadpisi i ikh znacheniye dlya istorii Peredney Azii, ZhMNP, 1875, p. 5

9. Adonts N. Noviy entsiklopedicheskii slovar Brokgauza-Efrona

10. Istoriya armyanskogo naroda, Yerevan, 1980, pp. 17-18

11. Abegyan, Manuk Istoriya drevnearmyanskoy literaturi Yerevan, 1975, p.11

12. Manandyan, Ya.A. Tigran Vtoroy i Rim Yerevan, 1943, pp. 27, 47-48, Mamedova, Farida Politicheskaya istoriya i istoricheskaya geografiya Kavkazskoy Albanii, pp. 118-120

13. Mamedova, Farida, op. cit. p. 119

14. Istoriya armyanskogo naroda, Yerevan, 1951, p. 266

15. Istoriya armyanskogo naroda, Yerevan, 1980, pp. 171-172

16. Efendiyev, O. Territoriya i granitsi azerbaijanskikh gosudarstv v XV-XVI vekakh, pp. 114-116

Rokhborn, K. Nizami-i eyalat dar dovre-ii Safavii, Tehran, 1970, p. 6

Rakhmani, A. Azerbaijan: granitsi i administrativnoye deleniye v XVI-XVII vekakh, see Istoricheskaya geografiya Azerbaijana, p. 132

Bidlisi, Sharaf-Khan, Sharafname. Perevod, predisloviye, primechaniya I prilozheniya Ye.I. Vasilyeva, Moscow, 1976, vol. 11, pp. 174, 198

Rokhborn, K. Nizami-i eyalat dar dovre-ii Safavii, Tehran, 1970, p. 6

Rakhmani, A. Azerbaijan: granitsi i administrativnoye deleniye v XVI-XVII vekakh, see Istoricheskaya geografiya Azerbaijana, p. 132

Bidlisi, Sharaf-Khan, Sharafname. Perevod, predisloviye, primechaniya I prilozheniya Ye.I. Vasilyeva, Moscow, 1976, vol. 11, pp. 174, 198

17. Chavchavadze, I. Armyanskiye ucheniya i vopiyushchiye kamni Velichko, V.L. Kavkazskoye russkoye delo i mezhduplemenniye voprosi, Baku, 1990, p. 107

18. Spravka prokurora Echmiadzinskogo sinoda Frenkelya A., 1907, TsGIA, collection 821, catalogue 139, case 173, stock 96

19. Bolshaya Sovetskaya Entsiklopediya, Moscow, 1926, vol. 3, Armyanskiy vopros p. 436

20. Istoriya armyanskogo naroda, Yerevan, 1980, p. 259

21. Lt-Col Tverdokhlobov, commander of the 2nd Erzurum Castle Artillery Division, Memuari russkogo ofitsera, Academy of Sciences, Azerbaijan SSR, History series 1989, No 1

22. Balayev, Aydin Azerbaijanskaya Demokraticheskaya Respublika, Baku, 1991, pp. 17-18; Dekreti sovetskoy vlasti, vol. 1, pp. 298-299

23. Balayev, Adyin, op. cit. p. 50; TsGAOR, Azerbaijani SSR, collection 970, catalogue 1, stock 1, p. 1

24. Bolshaya Sovetskaya Entsiklopediya, vol. 3, Armyanskiy vopros, p. 437; Grazhdanskaya voyna i voennaya interventsiya v SSSR (Entsiklopediya), Moscow, 1987, p. 43

25. Balayev, Aydin, ibid.

26. Bolshaya Sovetskaya Entsiklopediya, p. 437

27. Op. cit. p. 438

28. Ibid.

29. Grazhdanskaya voyna i voennaya interventsiya v SSSR, p. 42

30. Op. cit. p. 43

31. TsIA IML, collection 64, catalogue 2, case 5, p. 80

32. Kirov, S.M. Stati, rechi, dokumenti Vol 1, Moscow, 1936, p. 231

33. Dokumenti vneshney politiki SSSR, Vol 3, Moscow, 1969, pp. 598-599

34. TsIA IML, collection 17, catalogue 2, case 7, p. 13

35. Ibid.

36. Petrushevskiy, I. P.O. dokhristianskikh verovaniyakh krestyan Nagornogo Karabakha, Library of the Azerbaijani OZF of the USSR Academy of Sciences, N2 38990, 1930, p. 13