Camilla Rzayeva meets Narmina Mammadzadeh, a novelist, poet and artist, member of the Union of Azerbaijani Writers and winner of the 2014 Golden Pen literary prize. Oh… and all this in her free time.

Baku has many different faces, which change as you go from one street to another, like the turning pages of an oh-so-familiar book. As I drive to my interview, I pass many streets, all the time thinking that the new buildings, although grand, will never have the same appeal as those touched-by-time balconies with countless flowerpots.

The Caspian is glistening to the right as we approach Port Baku, the new, more formal part of our city. It’s lunchtime and the place is naturally busy. Among the sea of suits and ties and the orchestrated click-clack of high heels, I see Narmina. We greet each other and then as we head to the quietest café we can find she takes a business call, offering me a glimpse into the world other than the ones she creates on the pages of her books.

Our location is only a matter of convenience as it’s close to her workplace – BP Azerbaijan. It’s an unusual combination of interests, I keep thinking to myself, as she easily navigates a very technical conversation. She beats me to the question:

I think it’s precisely the incompatibility of my professional life and my creative side that makes them in fact quite compatible. I’m a Libra, which means both scales have to be full and that balance allows me to bring in good results on all sides of the spectrum of my activities.

But then what is the typical portrait of a modern day writer? Would you be able to spot one in a café, or is the gift of word not perceptible anymore? Young, intelligent, seemingly perfectionist to the tips of her carefully manicured fingernails, Narmina Mammedzadeh is a learning adviser at BP. Yet behind the soulful lines of her poems accompanied by her sensual photography, I would never have thought Narmina would be in such a technical profession.

But that’s just the beginning…

I’m not a magician, I’m just learning

When I first read an excerpt of Narmina’s work, I was intrigued – not often do I get to see a young writer in full control of her own voice.

Her dialogue with herself started long before her first book was conceived, in the form of poems that she wrote from a very young age. At 13, she started her first diary, which as she now understands consisted of stories and experiences of the day rather than typical diary entries. Since then the pages of many notebooks have been filled with colourful narratives and dialogues of how her young self saw life. It’s very likely that this is when the seed of writing prose was planted, which would take some time to transform into something more fundamental.

Her writing has taken a serious form in the last seven to eight years. Before that, she went through a period of not writing at all, the reason being pretty straightforward – university required a lot of time and none was left for other pursuits.

It would seem natural for people who are writing from early on to seek education in a related field, so I’m intrigued once more when on the contrary Narmina says: I always wanted to be a lawyer, I saw myself as a judge, lawyer, even a prosecutor. She even experienced that role, having graduated in International Law from Baku State University, at the prosecutor’s office for six months, but soon understood it wasn’t for her.

Her career in HR and education started at the United Nations, where she was responsible for developing local NGOs, after which, in a manner characteristic of her, she honed her skills by completing a distance learning degree in that field as well.

In a similar way, in 2011, when she released her first compilation of poems, The Four Seasons of One Soul, she decided to create the cover herself. But at the highest level of course, so she studied another four years with an art tutor, religiously attending the lessons.

Then in 2012, by the will of fate, as she likes to say, she sent her manuscripts to Chingiz Abdullayev, a renowned writer and secretary of the Union of Azerbaijani Writers. A folder with eight short stories was accompanied by an introductory letter with a quote from the old Soviet film adaptation of Cinderella. It said, I’m not a magician, I’m just learning, which is used quite often in the post-Soviet world to mean don’t ask too much of me, I just do what I can. By sending it to the Writers’ Union, she wanted to know his opinion of her writing and whether she should pursue it further or not.

Imagine her surprise when a week later, she received a phone call from Abdullayev himself. Not only had he read her full portfolio, he’d also left notes with his suggestions culminating in a short verdict – publish.

It’s our human nature to need that support, Narmina says. Yes, we’ll do some things anyway, but sometimes even a nod from someone can do wonders. To this day I tell him that he probably was that push that I needed to continue writing, because those were my first short stories and naturally I wasn’t so sure about them.

Debut novel

After his definitive yes! she soon wrote and published her first novel, Taroki, which, she explains,

… was the first time that I risked writing more than my usual word count. You realise it’s more than a short story when new characters are born, each with their own fate.Fitting one fate into a short story is one thing, but it takes much more to tell the intertwining fates of several people with the right level of attention. And you feel personally responsible, it becomes your mission to tell the story told to you by the character in your head who you imagine to be peacefully sitting next to you.

More often than not I write as a reaction to something, a film or a story that moves me

For Taroki, she spent a long time looking for a game uniting several people, preferably five. The overused Monopoly was soon dismissed in favour of card games, especially when she found out, purely by accident, that tarot cards hadn’t always been used for fortune-telling; they were created as playing cards for a specific game in which points had to be counted. My aim, however, was not counting points, but to bare the human soul, Narmina says.

So she invented her own game: five players take turns and pick a card to make a confession about their life. The person with the most powerful confession wins. To be honest, it was a game to pour your heart out to absolute strangers, because maybe they didn’t have anyone they could confess to without the risk of being betrayed.

Some method acting was then applied by ordering a set of tarot cards, playing with invisible characters, unveiling their stories and secrets. More often than not I write as a reaction to something, a film or a story that moves me, rather than from myself. I invest a piece of myself in everything I do, but I write more about what I absorb, she says.

Her fictional characters bear traits collected from people in real life, but you can also see a bit of Narmina herself in the main character’s phrases and habits.

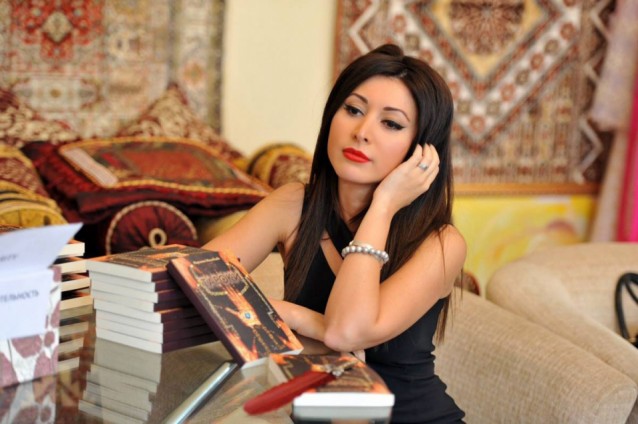

The book launch of Memories in Celcius, which was combined with a solo art exhibition. Photo: courtesy of Narmina Mammadzadeh

The book launch of Memories in Celcius, which was combined with a solo art exhibition. Photo: courtesy of Narmina Mammadzadeh

Four books later, she has acquired quite an audience and each year as it grows, so too does the responsibility for what she puts on paper. Realising this, she nevertheless voices her opinions confidently, in the most diplomatic way possible.

Given her hectic work schedule, Narmina mostly writes at home, her only company being classical music: Sometimes it’s not as easy to find time to spend alone with my thoughts, I’m always surrounded by people; I only write after work, in the evening, alone, in my headphones.

Sleeping only five hours a night, she is otherwise constantly on the move, attending events and paying respect to her wide circle of acquaintances: Friendship is a job, actually any relationship is a job, but especially friendship. And if we don’t spend enough time, attention or put effort into preserving that relationship, it most likely won’t last. And that includes meetings, calls… any sort of support.

Nonetheless she applies a similarly diligent approach to her deeply permeable writing as she does to perfectly balancing a corporate job with her creative and social life:

I always look at what I’ve written first, since I’m a firm believer that the text should be represented as cleanly as possible. Otherwise it’s not respectful towards the reader: it shows negligence and conceit.

The Seventh Doll

I immersed myself in what I was writing, I literally had tears in my eyes

The form in which she delivers her work is impeccable and the content itself makes you feel like you’re invested in every written word. She learnt the value of this while working on her latest novel, The Seventh Doll of Douer, when one of her editors came back with a suggestion:

He said: when one of your characters dies you need to write in a way that would make the reader want to cry, that would almost tear their soul apart. Write it so that you yourself want to cry. And so I immersed myself in what I was writing, I literally had tears in my eyes. And you may consider it mysticism, but if I’m crying while I’m writing, my reader should be able to feel this while he reads. My mood should transcend to my reader.

The Seventh Doll is based in Baku and is about seven orphans who are placed under the patronage of a professor named Klaus Douer, a scientist to the core who is trying to solve the mystery of human character. But this isn’t any usual orphanage: Klaus, deeply affected by his own failed relationship with his father, decides to conduct an experiment. He chooses seven children from different families, teaches them to control their own feelings and the effects of the outside world, and most importantly how family or any other human connection involving love or attachment are overrated. As the children grow older, the professor notes how close (or far) these apples have fallen from their original trees, especially when they are introduced to the outside world, where each of them, regardless of what they have been taught, attempts to look for their families in one form or other.

The theme of mysticism is present in almost all of her work – this is something that attracted me from when I was a child. And with many of her stories being set in Baku, Narmina agrees that the culture of this city also influences her writing a lot:

I humanise the city, it’s not just buildings. It has a soul. In all my books I have a part about the city, usually the heart of it – Icherisheher. I often describe the narrow streets, Shirvanshahs’ Palace. Maybe it’s because my relatives were from there, I don’t know.

At The Seventh Doll of Douer book launch with writer Chingiz Abdullayev. Photo: courtesy of Narmina Mammadzadeh

At The Seventh Doll of Douer book launch with writer Chingiz Abdullayev. Photo: courtesy of Narmina Mammadzadeh

The power of a wish

A couple of weeks ago, she started her new novel. Usually, she says, after you publish something, for a period of time, you’re empty. It takes some time to write again. But this time it started unusually easily and despite almost never knowing how her novel is going to end, on this occasion she already has a title, which in the case of The Seventh Doll had taken some thinking.

Something Narmina says at the end of our conversation lingers with me as I walk back to the office: Nothing is impossible. Everything in life is tied to the power of a wish. If you wanted something and didn’t achieve it, you have to be honest with yourself and admit that you didn’t want it badly enough. Otherwise it would’ve been done, because the power of a wish is immense.

She certainly has acquired some of those traits she admires so much in Abdullayev. Talking to her, I was feeling equally inspired and motivated as she was after each meeting with him.

It’s incredible sometimes the people we get to meet in life. And how you meet them is another story in itself. Smiling at my signed copy of The Seventh Doll, I can’t help but be proud of yet another incredible acquaintance that Visions of Azerbaijan has presented to me. On behalf of our team, I wish Narmina even more creative inspiration and every success in the future.