Ever since I was a child, I have always heard that Baku in the 60s and 70s was a cultural hub where literature, poetry, art and music were at the epitome of its development. The world has changed a lot since then and neither has our city of winds been immune to the wheels of life and change. But even under the most relentless circumstances, jazz and art have always stayed inseparable parts of our city’s character.

It’s almost customary now for the second part of spring to be loaded with events and on a typical May Sunday, as the city was buzzing with preparations for the Islamic Games and Formula 1, some events had already begun: a helicopter was making wide circles around the city live broadcasting the Tour d’Azerbaidjan cycling race and an Instagram sensation, dancing millionaire Gianluca Vacchi, was walking around the streets of Icherisheher, preparing for one of the biggest parties due that evening. As I was en route to my destination, I noted proudly that on this sunny day Baku was at its best, hosting pleased tourists aiming their cameras at my city’s most beautiful sights.

There were two different reasons why I found myself in one of Baku’s finest buildings, the National Museum of Art, and both were equally important. It’s truly a joy that art in Azerbaijan is developing and living. And I’ve always thought that every city, every country in the world gives certain characteristics or part of its soul to the creations of its artists, making their work unlike any other. Recently, during my visit to Istanbul, my artist friend noted the unusual, almost green shades of sunset towards the ground. That’s why, she said, artists in different cities never draw sunsets the same. They draw what they see, and what they see changes with longitude.

In contrast to traditional still life and portraits, I felt a surprising freedom pronounced on almost every canvas

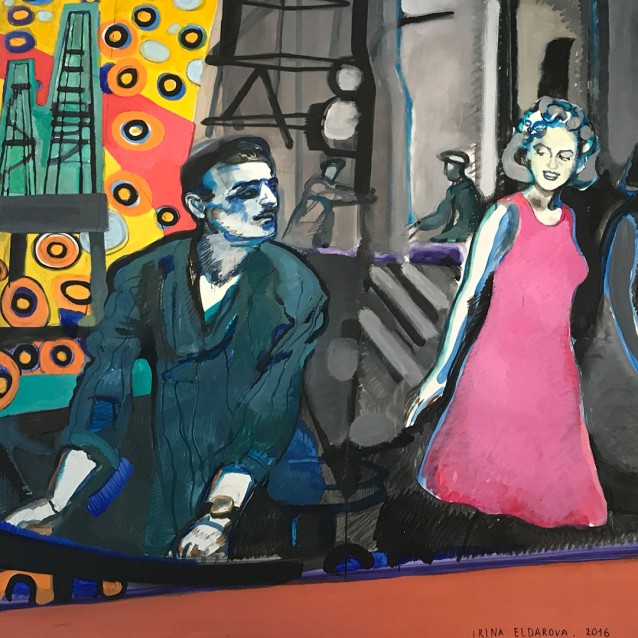

Walking through this grand building I was mesmerised by the architecture and how easy it would’ve been to get lost in all these rooms. Finally, wandering into the four rooms allocated for the Art Rising exhibition, I heard familiar music, the Chahargah mugham by Yasef, so perfect for the setting. This exhibition was organised to celebrate the start of Art Rising, a project dedicated to supporting and promoting young Azerbaijani artists in the world. The two-day exhibition included 20 young and 11 renowned artists and five sculptors. I skipped the opening night, preferring the quiet morning with not as many visitors in the first part of the day. Walking through the exposition rooms, the oil theme seemed to occur quite often – being the century-old synonym of Baku – with oilrigs surreptitiously showing in the background or creating dark shadows against the sunset. In contrast with the traditional still lifes and portraits, I felt a surprising freedom pronounced on almost every canvas. Daring and bold, young artists aren’t afraid to go beyond the conventional canons of art.

Qiybet or Gossip was quite an outcry of something that isn’t the proudest part of our culture. Depicting a man with his ear pressed to glass by the wall listening, and a woman looking all comfy, knitting, with a cat nearby, also listening in to the life of a family peacefully sleeping in their home. Human curiosity is natural and undoubtedly exists everywhere in the world, but it has somehow attained permanent status among the traits inherent in our people... to see behind the closed door, inside somebody else’s life.

I saw raging emotions on canvases, going from dark to light, but with the same undercurrent of the angst that rages in one’s soul in early youth. More mature artists, like Subhan Mammadov, chose softer shades and blurry lines, reminding me of my favourite Monet.

Some of the works spoke to me on a completely different level however, unexpectedly taking me down memory lane

I wondered how many hours it took to finish the highly detailed Dream, where the girl, all in black with a crescent moon at the top of her ponytail, was sound asleep; by the bottom of her bed horses were galloping, while at the top, over her head, were what almost looked like Nizami miniatures.

Some of the works spoke to me on a completely different level however, unexpectedly taking me down memory lane. A hot summer day, the dark blue waters of the Caspian and the remains of what used to be a summerhouse, the front part of which was painted in typical white. It reminded me of my childhood and the adventure of taking a 30-minute walk to the sea, and how all the kids rushed to the pleasantly cool waters because the sand was burning hot. Even the green thorny bushes depicted to the side of the house were accurate. Those bushes had tiny pink flowers which fell apart as you picked them, making it not worth the painful encounter at all. I remember seeing abandoned houses like that and how we weren’t allowed to climb there because there might be snakes inside. But childish enthusiasm knows no boundaries.

The wire installation Paradise Road took me to yet another memory, this time half the world away from here. I used to take the same road home every day, while I lived in Washington. The hill part of it was a blast to drive down, except in winter, of course, when the slippery roads scared the daylights out of me. There were trees on my Paradise Road, although not so tall and leafy as in this installation. But one striking resemblance was the treetops and how they were lighter than the rest of the tree. I remember, when the sun was setting, during what photographers call the “sweet light,” I used to love watching the tops of the trees turn lighter as the fading sun ever so slightly touched only them, making it look like they were glowing.

Greece, I thought to myself, it has to be Greece, as I looked at the bright blue door against the white wall, framed by pink and white flowers. The one next to it was a painting of the same place but from afar, the coziness of the same bright blue chair and table complemented by a grape tree finding its way up the wall to the window. The artist, Khanlar Asadullayev, preferred to leave the place unnamed, open to the imagination of the observer.

Among the myriad of emotions on canvases, by the window, in the warm rays of the May sun was the first time I saw Ballerina. Inconspicuous at first sight, it took me a minute to slowly walk around and catch the perfect light to appreciate it. The ballerina didn’t have a face and I liked that anonymity. Her hair was in a tidy bun, leaning on something; she had her legs stretched like a guitar string. Fragile shoulders, playful dress, dreamy posture, I wondered where her thoughts were at this time. Where did the master see this fragile creature…. and for how long was she lost in thought? At the opposite end of the room, looking at her, stood a second girl. The same prolonged features, only this one had a face and her full, unruly hair was down. Bending her head to the side, a coquettish gesture, standing on her tiptoes – there was something light, something child-like about her, even though this exists in all women, regardless of age.

I was leaving the place with a mixture of emotions, bittersweet, to say the least. There was so much talent there and so many opportunities of many more exhibitions and future admirers of their talent. Except for one. The piece of paper with his name moved back and forth with the wind from the single open window in the room. Ballerina by Samir Kachayev, it said. The second statuette by him was The Coquette across the room, looking in at Ballerina. Were they made in the same time period? Was it the same girl? By the gestures, I’d say it could have been.

Last April, Samir’s name was on every news website. Even though we’d never met, my Facebook feed was covered with his photographs, shared by his friends, friends of friends, our mutual friends. In the 25 long years of war, we hear about ceasefire violations from both sides every day. And every day every family from the two estranged neighbour-countries hopes that there are no fatalities. April 2016 saw the largest ceasefire violation since the agreement of 1994. In what we now call the Four Day War, among many others, Samir Kachayev was fatally wounded.

The nature of a “frozen conflict” may sometimes make it seem like there is no war at all. Unless it touches you directly and cuts your soul into pieces, never to be whole again.

Too young to be gone so soon, seeing Samir’s statuettes as the last thing we’ll ever see from him made our current situation even more relevant. Samir was a dear son, a good friend, a talented artist…. a source of pride that this country will never have a chance to present again.

My biggest hope, as I was silently exiting the museum, was that one day there will be peace between our countries and mothers won’t lose their sons, as the arts won’t lose their masters. And maybe then a new cultural awakening will see the light of day…