Following the Great Northern War and having led a successful military campaign in the West, Peter I (1672-1725), the last Moscow tsar and first all-Russian emperor, began thinking about moving east, towards Persia, India, China and beyond. He had one main goal – to further enlarge and enrich the state treasury.

Peter considered this possible above all due to the oil resources available on the territory of present-day Azerbaijan, which were already providing a huge income for the treasury of the Persian king. According to reports to the emperor by the Collegium of Mining the local people were receiving “a huge income” from oil extraction on the Absheron peninsula. According to documents, the Persian shah had an average annual income of up to 7,000 tumans (about 50 thousand rubles) from trading oil with countries of the Near and Middle East. These oil resources, as well as other riches of which Peter was aware, accelerated his military incursion into Persia under the pretext of protecting the lawful authority of the shah.

EARLY RECONNAISSANCE

As early as 1465, Farrux-Yassar Hasanbey, an ambassador of the Shirvanshah, paid a visit of friendship to Moscow’s grand prince Ivan III. The following year, in 1466, a delegation from Moscow led by Ambassador Vasily Papen paid a reciprocal visit to Shamakha, the capital of the ancient state of the Shirvanshahs.

The delegation included merchants, among whom was Aphanasy Nikitin, a renowned traveller of the Caucasus, Persia and India, and merchant from Tver. Nikitin had visited Baku and reported back to the tsar’s court about the region’s valuable Eastern goods (Shirvanshah silk, Mugan cotton, Karabakh carpets, Baku oil and salt). He left a diary of travel notes, Walking Beyond Three Seas, in which he comprehensively described his four years of traveling across Persia and India.

Prior to this, information on Baku’s available oil resources had already come to light in old Caucasian Albanian written sources from the 7th and 8th centuries. Later, in the 13th century, Venetian traveller and merchant Marco Polo and Arab scientist Mohammed Bekran noted that life on the Absheron had long been connected with oil. Marco Polo, having travelled across Central Asia from the eastern coast of the Black Sea to China, wrote that even then oil was being transported from Baku on camels to neighbouring lands and used as lighting fuel and for medical purposes.

SIEGE OF SHAMAKHA

The pretext for Peter I’s military campaign in the Caspian region was also fed by his desire “to punish” rebels for the harm caused to Russian merchants trading in Shamakha where numerous merchant colonies from different states, including Russia, were based. Russian merchants traded in cities near the Caspian Sea and along the Volga region - Astrakhan, Tsaritsyn, Yaroslavl and Nizhny Novgorod. Trade links between Astrakhan, Moscow and Vologda, and through the latter with Arkhangelsk, enabled ships with Russian goods to sail through to Central Europe and beyond.

In August 1721 the feudal ruler and head of the Sunni religious branch of Islam in northeastern Azerbaijan, Haji Davud Mushkursky (Gubinsky), having taken charge of an anti-Persian movement and acting together with Dagestanis and mercenaries, laid seige to Shamakha and captured the city. Robberies, especially by mercenaries, began and all the merchants in the city (including Russians) were plundered and severely beaten, which caused extreme discontent in Russia.

So, there was a main goal (replenishing and enriching the tsar’s treasury with the future capture of areas along the Caspian) and now there was a pretext. Due to the unusual character of the first emperor and his uncontrollable temper, the military invasion was not long in coming. During the 1722-1723 campaign, Peter I intended to march on Baku, Tabriz and other areas of the Caspian coastal region. To achieve this he needed not only to capture the narrow coastal strip, but also to go deeper into the heart of the South Caucasus.

|

Peter’s Character Peter the Great has long polarised opinions among historians. The first strictly academic character assessment of Peter I was given by Professor Henrik Leer (1829-1904), chief of the Academy of the General Staff in St. Petersburg, who wrote: ... he possessed an unusually developed creative mind, an ability to meet critical moments calmly. At the same time he was also a deep psychologist, capable of influencing the soul of a soldier [...] he was one of the few commanders who were able to do everything, could do everything, and wished to do everything [...] Peter was a commander of the highest level, for whom “broken roads simply did not exist.” In organising the Russian army according to foreign standards, applying and re-creating Russian military techniques and imitating and borrowing foreign practices, he was always able to preserve the original foundations of national ingenuity. Russian military affairs under him far outstripped those in Europe. By contrast, the well-known Soviet historian Militsa Nechkina believed: as a person Peter I combined huge willpower, a talent for organisation and ability to take initiative with an extreme mental disbalance, cruel behaviour, habitual drunkenness and unrestrained debauchery. Nechkina also considered: a number of Western historians and researchers idealised Peter I as a symbol of “statehood,” hiding his dark side and incorrectly considering his reign a sharp turning-point, while in fact it only distinctly developed traditions that had already begun to take shape earlier. |

PREPARATIONS

Peter’s administration developed an extensive programme of political and economic measures for the South Caucasus, given that Russia’s growing industry needed the raw materials available there. But Russia was also concerned about attempts by Ottoman Turkey to capture the region first and establish itself on the Caspian coast. Therefore Peter aspired to construct a large city there with a naval base in order to strengthen Russian influence. Considering Baku the main trading point between the countries of the East and Russia, he wrote:

There will be an extreme need for us (the Russians) to capture the shores along the Caspian Sea, because… we can’t allow the Turks here.

With this in mind, in 1719 a hydrographic specialist named Fyodor Soymonov was instructed to explore, measure and describe the Caspian Sea, which he carried out between 1719 and 1727, visiting the Caspian Sea four times (in 1719, 1722, 1723 and 1726). In 1731, the first complete atlas of the Caspian Sea, compiled by Soymonov, was published. Its title was A Description of the Caspian Sea from the Mouth of the River Astarabad, Western and Eastern Coasts, Depths, Soils and Views of Notable Mountains.

Prior to launching the military campaign, on 15 June 1722 Peter announced the purpose of the iminent invasion in a document entitled Manifesto, written in Azerbaijani. In it he noted that Russian merchants had come to the region to trade according to ancient customs (Russian merchants had been known to trade in Shamakha since the 12th century). The manifesto was the first printed document in Azerbaijani, published and distributed in Azerbaijan. It was sent to the main cities of Shirvan: Baku, Derbent and Shamakha and areas along the Caspian.

Of course the real aims of the campaign remained hidden in the manifesto. Instead, he masterfully exploited the religious factor by convincing the local Shia population that he was a friend of the Shah and that the aim of his mission was to establish order in the region. At the same time it was explained to the Christian population of the South Caucasus that the campaign’s purpose was to liberate them from Muslim oppression.

Peter I prepared seriously for the campaign in Persia: information was gathered about the country and its possessions, as well as detailed material about its oil and other resources. For example, in 1716, long before the military campaign began, the Russian ambassador to Persia, Artemiy Volynsky, had been given a top secret assignment, the basic purpose of which was to study caravan routes and the state of local defences, to locate suitable pastures for the cavalry, establish relations with local Christians and study the prospects for developing Russian trade in Persia (particularly in Azerbaijan).

Volynsky executed Peter I’s assignment brilliantly and returned to Russia in 1718 having concluded a favourable trade agreement with the court of the Persian Shah Hussein. Later, he would participate in the Persian campaign of 1722 together with the emperor. But prior to this, in 1720, Peter also sent his associate, Captain Aleksey Baskakov, to Persia in order to smooth over trade relations there (and subsequently with India) and carry out reconnaisance.

SETTING SAIL FOR THE CAUCASUS

On 18 June 1722, a Russian flotilla consisting of 274 ships commanded by Peter I and Admiral Fyodor Apraksin sailed south from Astrakhan. The Russian army moved in two directions – by sea and by land. The importance of the Persian campaign for Peter I, in which oil played a significant role, is also indicated by the fact that he took his wife, Catherine I, with him, leaving Prince Aleksandr Menshikov in charge of the government in St. Petersburg.

On 15 August 1722, an army of almost 50,000 men was located north of Derbent. The port of Petrovsk (nowadays Makhachkala) was founded at the place where Peter I disembarked. Under the emperor’s personal supervision the settlement of Tarki, whose chief had earlier accepted Russian citizenship, was occupied, and then Derbent was taken without a fight. Interestingly, Peter I’s presence in Derbent on the 23 August coincided with an earthquake. Unabashed, he told his wife and surrounding entourage: Even nature shudders before my power….

During Peter I’s stay in the Caucasus in August 1722 he was visited by representatives of all social classes from Derbent, Baku, Salyan, Resht and other cities. He sent a letter to the senate in which he wrote that he was warmly met by the population. But this was not completely true: the Sultan of Baku, Muhammad-Hussein bey, relying on his own forces and the help of Haji Davud, was ready to defend the city and therefore he did not receive the messenger bearing Peter’s letter.

Soon, in light of various circumstances – new threats of war came from Sweden, as well as the danger posed by Turkey, which had already dealt Russia a series of big losses in the northern Black Sea region and the Balkans – on 7 September 1722 the emperor returned to St. Petersburg. However, on 5 November he issued the following instruction from Astrakhan to Major General Mikhail Matyushkin, the commander of all troops in the Caucasus and the Caspian: When the 15 gekbots [Russian warships - Ed.] arrive from Kazan in the spring, then go by them with four regiments to Baku and take it.

Before the flotilla set sail Matyushkin received a further order from the emperor: go to Baku and conquer the city with the help of God, because it is the key to all our business….and the protection of this place is of the upmost importance, because we are doing everything for it.

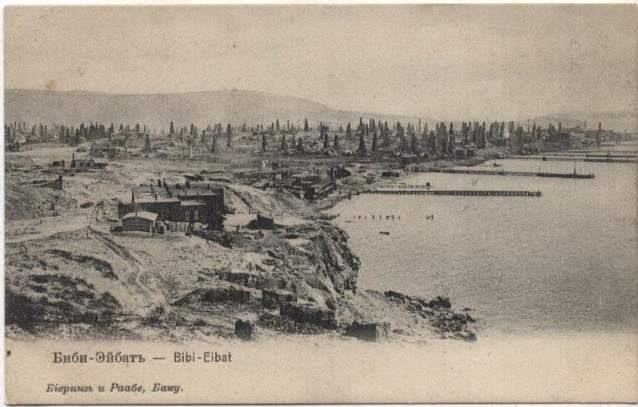

In July 1723, Matyushkin landed on the Absheron peninsula and after a four-day siege of Baku entered the city without a fight. By August 1723 almost the entire western and southwestern coastline of the Caspian Sea had been occupied by the Russian army, much to the credit of Major General Matyushkin.

The capture of Baku on 28 July 1723 pleased Peter greatly and magnificent celebrations were arranged in the streets of St. Petersburg. The colonel and prince, Ivan Baryatinsky, was appointed governor of Baku (later a street in the city was called Baryatinskaya, which was renamed Fioletova in 1920 and then Alizade in 1991). Following the capture of Baku, Salyan was also taken.

Peter I believed that only by taking possession of Baku’s oil could Russia strengthen its foreign trade relations with the East and Europe. Therefore, in 1723 he wrote to Major General Matyushkin, ordering him: take some poods of white oil from Baku and send or bring them yourself to us.

Later another order followed: Send thousands of poods or as much as possible of white oil and look for an expert.

Naturally, the emperor’s orders were carried out, and both Matyushkin and Soymonov made a detailed inventory of all of Baku’s oil fields, which subsequently became the property of the imperial treasury.

In his work, Items Relating to the Modern History of the Caucasus from 1722 until 1803, the Russian historian Pyotr Butkov noted that after capturing Baku: the property or income of the treasury were taken under Russian administration. These consisted of two main items for sale: salt and oil, and as far as is known, they brought 50,000 roubles in to the Russian treasury each year.

CONSEQUENCES

As a result of Peter I’s Caspian campaign, Russia acquired the western coast of the Caspian Sea together with the cities of Derbent and Baku, as well as the southern coast with the city of Astarabad, under the Treaty of St. Petersburg of 12 September 1723. In return, Russia was obliged to assist Persia in the war with the Afghans.

Russian successes on the Caspian mobilised Ottoman Turkey, which had already sent its forces to the South Caucasus in the autumn of 1723. Later, Russia and Turkey signed an agreement in Istanbul on 12 July 1724 under which the South Caucasus was divided between these two powers. Turkey recognised Russia’s right to the Caspian coastal areas (including Derbent, Baku, Salyan, Lenkeran, Resht and Enzeli), and in return Russia bound itself not to counteract Turkish influence in other parts of the South Caucasus.

In such a way, whereas in the Middle Ages Baku’s oil industry had been monopolised by the Persian Shahs, under Peter I the city’s oil resources passed into Russian hands. Ultimately, with the acquisition of Derbent and especially Baku, as well as the adjoining coastal areas, the beginning of Russia’s long conquest of the Caucasus had begun.

However, following Peter I’s death on 28 January 1725, England, France and Turkey began to oppose Russia’s Eastern policy and Nadir Guli khan Afshar (the future Nadir-Shah) waged a successful war to restore the former borders of Persia. All of these four countries resisted the strengthening of Russian influence in the Caucasus by any means and during the Persian-Turkish wars of 1730-1735, Russia, under the terms of the Resht (21st January 1732) and Ganja (10th March, 1735) treaties, surrendered the Caspian coastal areas to Persia.

In such a way Peter I’s policy towards the South Caucasus – opening the way to the East, transforming the Caspian Sea into an internal Russian sea, taking possession of Baku’s oil resources and trading with the countries of the East via the Volga-Caspian route – only began to be realised 88 years after his death, once the Baku oil region had fallen again under the sway of the Russia Empire following the Treaty of Gulustan (12 October 1813). According to the terms of this treaty Persia recognised Russia’s annexation of the northern Azerbaijani khanates, and this ushered in almost two centuries of Russian control and influence over the South Caucasus.

About the author: Mir-Yusif Mir-Babayev is a professor at the Azerbaijan Technical University and a doctor of chemical sciences.