"Oczen cholodno," the driver of the jeep who deposited us at the trailhead had said, gesturing up the valley to where the mountain was hidden behind the intermediate ridges, "it’s very cold". He took the fabric of our waterproofs between finger and thumb and added something in Russian that neither of us understood, but obviously meant, what on earth are you doing going up a 4000 metre mountain like Shahdag at the end of winter dressed like this?

"Oczen cholodno," the driver of the jeep who deposited us at the trailhead had said, gesturing up the valley to where the mountain was hidden behind the intermediate ridges, "it’s very cold". He took the fabric of our waterproofs between finger and thumb and added something in Russian that neither of us understood, but obviously meant, what on earth are you doing going up a 4000 metre mountain like Shahdag at the end of winter dressed like this?Eight hours later, waiting for the water to boil as dusk fell rapidly where we were camped below the peak’s eastern flanks and the cold came down round around us, it seemed like a good point. We’d left Baku at 7am by microbus, and got into Qusari, the nearest market town to our goal, three hours later. The Saturday bazaar was in full swing behind the bus station, the last before Novruz, the four-day long spring festival started, and the spaces between the microbuses were filled with gold-toothed, flat-capped men, bundled- and head-scarved women, colorful piles of fresh fruit and vegetables, even more colorful piles of bakhlava and gohar, doners, kebabs and hot sweet tea. In Azerbaijan, you dunk the crude sugar lumps in the tea for a moment and then suck them dry, which may account for the ubiquity of gold teeth. We were going to miss the tea. Our lift to Laza, the village nearest the trailhead, arranged through the mountain guide in Baku who had also given us details on the tourist route, hadn’t turned up. After hunting around the bus station, and having a surreal interview in pidgin Russian with the local police chief - the border to the North, with Dagestan, is closed to foreigners - we struck lucky in an old battered Niva jeep and it’s equally battered but solid driver, who took us up the rough track, precipitous and in places visibly crumbling as we passed, for $20. In more pidgin Russian we’d arranged for the driver to be waiting for us at the same spot 4 days later, and, we’d stressed, to wait – we might not be exactly on time.

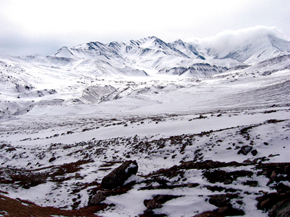

The walk up to the first camp site had been straightforward enough; the weather was excellent, the surroundings breath-taking - one of the most fascinating things about working in Azerbaijan is that you can get so easily from the post-Soviet industrial desolation of the coastal strip, stained with oil and strewn with all kinds of rubbish, to unspoilt beauty, and from desert to upland green pastures, or snowbound peaks. We’d only got lost once, as the horse track we were supposed to be following was still under the snow, but after wallowing around in drifted stream beds we’d got back on track. Our packs were heavy, principally with food, but we’d a minimum of gear, taken only in case the final ice slopes required roping up.

The first night passed slowly enough, waking in the cold every few hours and dozing again, twisting about in our bags to see what time it was and how much more of this remained till dawn brought warmth, and a hot breakfast, but it was in the knowledge that the next day would be easy. On Sunday we planned only to walk up through a narrow subsidiary valley through the ’Gates of Shahdag’, pitch the tent again at about 3000 metres, and get a good night’s feed before getting up again in the dark and slogging the 1200 metres and several kilometers to the summit. My partner, Tony, who has done this kind of thing before, recommended a head-torch-light start as a genuine mountain experience. Previous to this, the only time I’d been on a mountain over 3000 metres had been by cable car in the Dolomites, and my head torch experience had been mostly limited to the walk back from various crags.

Shahdag - dag is mountain in Azeri, and other Turkic languages, and you know what shah means - at 4243m is the highest mountain that is completely in Azerbaijan, (Bazarduzu, the higher peak, lies on the northern border). The summit plateau is ringed with crags, so there’s no straightforward path up to it; instead there’s a 45- minute traverse of a ledge - the ’balcony’ - which gives access by scrambling up a scree slope to an intermediate plateau, followed by a long but level slog at over 3500 metres to another steep scree slope whence a final snow slope leads to the large and featureless summit plateau. The only map we had - the only one apparently available - was a 1:10,000 Soviet-era map downloaded from the internet, and not sufficiently detailed to be of very much use in identifying the details of the route; we were instead relying on the description given us by the guide in Baku, and photographs he’d provided us with, with timings and the route penciled in. So far the features we were looking at had matched what he’d drawn on, so everything was going well.

Things stopped going well that afternoon after we’d made the second camp beside a stream gurgling audibly under the ice. That morning the stove had hissed away feebly for an hour before producing enough water for the powdered milk, and a decidedly lukewarm mug of tea. Now Tony worked on it desperately before calling across that it wouldn’t light. The verdict was that the fuel was dirty, and had clogged the valve; in any case, now we were down to bread and cheese and corned beef, as well as chocolate and trail mix. At least after a brief scraping clear with an ice axe, the stream gave us clean, fresh water, and seemed unlikely to freeze up during the night. But without the promise of a hot meal we were too despondent - or simply too cold - to want to reconnoiter the balcony and the scree slope above it for the next day, so we turned in as soon as the sun went down. As I filled and closed my water bottle for the next day I thought I’d ruined the threads of the stopper but then realised it was ice forming on them as I tried to screw it closed. Seven o’clock on Monday morning the 20th March -the last day of winter in Azerbaijan - saw us on top of the subsidiary peak of Kabash, having negotiated the bal dawn. We were already an hour behind schedule having lain in our sleeping bags, forcing down dry, semi-frozen food with swigs of icy water and putting off the moment of leaving the cocoon of approximate warmth around us.

From the top of Kabash the route was clear in the morning air; the sweep of the big cirque around the valley of the stream that fell down to feed through the Gates of Shahdag below us; the north western end of the summit plateau and the scree slope up to the saddle that gave access to it. The summit plateau itself was hidden in cloud. So we put our heads down and slogged around the edge of the cirque. At the end of it we dropped off slightly into deeper snow and started swapping the lead, breaking trail through snow at times thigh-high. As we stopped for trail mix and chocolate and to put on crampons at the bottom of the scree slope, it was starting to snow. Halfway up the scree, I fixed on a boulder indeterminately visible in the murk above me and started counting steps, trying to force myself to keep the same intervals before stopping to rest. The boulder just kept on not getting closer... When the ground began to level out and the wind strengthened in my face, I pulled off my sack and dropped on it in the snow, exhausted.

According to Tony’s altimeter, we were at 4000 metres; next, according to the pencil sketch, was the snow and ice slope that gave onto the summit plateau. We peered through the flying snow, squinting against the diffuse glare, unable to see much above us, and we started up the slope, loose scree squealing under our crampons; we were on no snow slope yet. After 20 minutes painful progress the slope leveled out again. We were still short of the midday cut-off point at which we would have to return, but we were going more and more slowly. We could see a narrow spur ahead of us, at the end of which the plateau spread left and right - none of which was in accordance with our version of the terrain. We sat panting on our packs in the snow. There had been features on the way up that had been omitted from our pencil-sketch-map, but in good visibility the route hadn’t been hard to find. Perhaps the ice slope was just beyond what we could see in the snow? But we were already at 4100m. Around us the cloud cleared for a moment; the dark crags ringing the summit plateau bulked ahead to our left, still a long way off, and still visibly higher. As the cloud returned, we made a decision; we’d been told that on the featureless summit plateau it was possible to wander for hours if you missed the summit marker, and these were not conditions, working from unreliable information, to be risking that in. We turned our backs on the summit and set off down the mountain.

Twenty minutes later, we were unstrapping our crampons and stepping out again across the lower plateau. We walked heedlessly into a whiteout. By the time we stopped to take a back bearing we couldn’t see where we’d started from, so we walked on a general bearing until we got among a lot of topographical features that I was sure we’d not passed before. We stood panting and dehydrated in the whirling snow, cursing ourselves for not having taken ’back bearings’ earlier, and then, holding a compass out to keep on the same line, set off in what we hoped was the direction of the crags around the edge of the plateau; they at least would be a ’collecting feature’ and allow us to relocate. What followed was four hours of floundering in the snow, trying to match the glimpses the weather gave us with our memory of the terrain, and our map. In the even white glare it was rapidly impossible to judge anything accurately. Was that slope opposite us two hundred metres away, or two kilometers, or more? Did the slope here - just here, in front of my boots - rise or drop away? I found myself poking the ground with my poles to find out. The rocks moved and swam against the featureless background. We discussed sitting it out, wondering at what point we were going to be forced to dig a snow cave.

We must have been doing something right because when the snow did begin to clear, we were going in the right direction, and more than half way back to Kabash. We sat by the cairn where we’d been at 7am, ten hours earlier, drinking and chewing stickily on our emergency chocolate ration, dizzy with relief.

Which was short-lived. We put our crampons back on and gingerly made our way down the snow-covered scree slope towards the beginning of the balcony. Stones shifted under the crampon points, as the angle steepened and a low rockstep loomed below. Beyond that was it was a long way to the next level ground. We returned to the top of the slope and began to consider our options, again. We could try to abseil down the icefall, but with the minimal gear we’d brought, we’d be relying on abalokof threads; we didn’t think we had enough rope to abseil it in one go. There was an alternative tourist route, but it was - somewhere - on the other side of the cirque; we’d be looking for the entry ramp onto a steep 600- 700m snow slope in the dark. What we didn’t consider was phoning for the mountain rescue services: Azerbaijan has none, and hasn’t had since perestroika, as the mountains aren’t invested in as a tourist resource at all. In any case we’d been out of range of the mobile phone network since Saturday morning. Apart from the driver of the jeep, we wouldn’t be missed till we failed to show up for work after the weekend. Eventually, through dehydration and melodrama, we realized that this couldn’t be the route down to the balcony: it was supposed to be the normal tourist route, but this would be equally impossible in summer, when the mountain is popular. We dragged ourselves along the slope another few hundred metres and found our tracks from the morning, almost imperceptible in the fresh snow: we’d tried to come down too soon.

Even the tourist route required a few metres of frontpointing with crampons and ice axe over the loose rocky steps, but after this point, despite tiredness and dehydration, it was now downhill all the way back to the tent. We’d both said that we would stand and drink a whole bottleful of water when we got back, but the temptation of the sleeping bags was too great. Nauseous with effort and lack of food, I forced myself to eat mouthfuls of trail mix before drawing the cord of the ’bag shut around my face. The tent boomed in the katabatic winds and a rain of frozen condensation fell on us all night long.

The walk back down to the Niva waiting at the trailhead - which took longer than it had done on the way up - was done under beautiful blue skies, again. The only thing to disturb the fresh snow were two wolves which ran across the gates of Shahdag ahead of us as we descended, skidding and crunching, down the slope. The turning circle where the jeep was came into view from behind a slope, disappeared, came back into view... When we finally reached it, tottering up the rise, the driver threw out his hands to us. ’It’s you!’ he shouted. He must have thought he’d never see us again. There’d been a few occasions when it had occurred to me too.

Two hours later, having tipped our reliable driver handsomely - partly in gratitude, I suspect, at his being the sole witness to the event - we were sitting in a teahouse-cum-restaurant in Quba bus station, drinking hot tea and eating hot food for the first time in two and a half days. Taxi drivers swarmed around us, eager to make a fast buck from the rich foreigners, but were above such crude matters. For quite a few days yet, we would be, mentally, out on the plateau above the balcony, floundering in the snow, with the summit of the mountain rising from the clouds behind us.

About the author: Graham Martindale was born in Ireland and is a keen hiker, orienteer and climber. He works for the British Council.