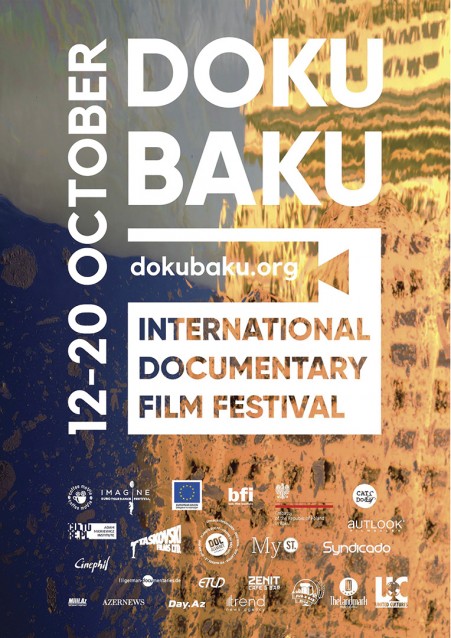

On 12-20 October 2017, the DokuBaku International Film Festival made history as the first documentary film festival in Azerbaijan. The meat of the festival was a series of screenings of 17 feature-length international documentaries in alternative venues like bars and pubs. The festival also drew out independent local filmmakers by hosting a competition among 15 short documentary film submissions. Sprinkled among screenings were concerts, Q&A sessions with filmmakers and masterclasses. In the run-up to the event, Visions writer Martha Lawry met with members of the organizing team Imam Hasanov and Aysel Akhundova to get the story on how the festival came about.

DokuBaku began as a sparkle in the eye of Imam Hasanov. He’s the tortured genius type: he constantly twists a rubber band around his thumb and can smoke his way through six cigarettes in the time it takes me to drink one cup of tea. Paradoxically, he is also a natural networker who builds community with his soft-spoken earnestness. Before we had managed to properly get acquainted, he introduced me to two or three other people he happened to know in Coffee Moffie, the movie-themed artists’ hangout in central Baku where we met to discuss the festival.

The evil of documentary filmmaking

Imam’s journey into filmmaking began pretty much like anyone else’s: with a degree from Azerbaijan State University of Art & Culture and then some practice honing his skills as a technical director. He planned to develop a fiction film, but quickly realized that the finances and technical expertise needed for that type of film were prohibitive. Imam was drawn to the idea of making a documentary film because, as he explains, documentary has fewer rules than fiction. You can make a film with a smaller budget; you can use your own conventions. He describes documentary as a good first step into the film industry.

But that’s not to say that documentary filmmaking is straightforward or easy. In this genre, it’s not so much that you as a director make a documentary; it’s more that the documentary makes you. You dance with destiny, throwing your cards to the wind and continually re-interpreting what you see taking shape as the situation changes. As DokuBaku coordinating team member and emerging filmmaker Aysel Akhundova explains,

Documentary filmmakers are sometimes called evil because the more turmoil there is, the better it is for the filmmaker; the more interesting it turns out.

In keeping with their industry tradition of taking risks and rolling with the punches, the small group of friends organizing DokuBaku has themed the festival “Testing Reality.” The name is meant to encourage young filmmakers to try out new methods and validate their unique perspectives. But the name is relevant on another level too:

We joke that we’re testing reality ourselves by holding this festival in Baku, just to see if it works, says Aysel. We had the idea to organize this festival, but none of us have done this before. We’re pioneers, just trying to do our best, and we believe that the passion we put into this will pay off.

From cow to community

they were really unusual eyes; sort of between dark and green. I started taking photos. I went to see his place right away and it was very cinematic.

The team’s do-it-yourself spirit is apparent in Imam’s own story of how DokuBaku was conceived. Five years ago while he was mulling over ideas for documentaries, he visited Lahij, a mountainous village in the Ismayilli region, to film a news report as part of his job at that time for AzTV. He happened to hear about a man in the village with plans to import a cow from Europe. Imam went to meet the man, Tapdiq, and immediately felt drawn to document his life as a project.

When we met, I saw Tapdiq’s eyes - they were really unusual eyes; sort of between dark and green. I started taking photos. I went to see his place right away and it was very cinematic. I talked to his family. His wife was afraid; she didn’t want to be in a film. But Tapdiq agreed to do it.

Imam started filming the family that same day. He continued to visit the village over the next three years to produce his documentary, which was released in Europe as Holy Cow in 2016. The film has won awards from CAUCADOC and DOK INCUBATOR (Czech Republic), EBS International Documentary Festival (South Korea) and South East European Film Festival in Los Angeles. I wanted to know how Imam managed to film such raw family conflicts, like the scenes where Tapdiq’s wife cries and says she won’t take care of a foreign cow. This is where Imam reveals his community-building magic:

People were friendly and open to me, so they stopped noticing the camera. They didn’t care about it. After we came and went for a year or so, Tapdiq’s wife opened up to us. She became like my sister. Tapdiq also became a brother to me. He was asking me if I had a girlfriend; he even offered to find me a wife from the village.

The screening of Harmony at Etude Bar on 13 October. All films were subtitled in English and Azerbaijani to make them accessible to international audiences. Photo: courtesy of DokuBaku

The screening of Harmony at Etude Bar on 13 October. All films were subtitled in English and Azerbaijani to make them accessible to international audiences. Photo: courtesy of DokuBaku

It didn’t take long for Imam’s lone film project to blossom into a dream of a documentary filmmaking community. Imam collaborated with Veronika Janatková, a producer from the Czech Republic, to make Holy Cow. When the pair took it to European film festivals like International Documentary Filmfestival Amsterdam, people kept asking them if there were any similar festivals in Azerbaijan. The question finally became an embarrassment, and Imam fired up his self-starter motivation to create a festival from scratch. He explains his logic:

No one will come and say, “I want to give you money so you can make a festival.” Our problem is that we are always waiting for someone to come and change things. No one will. It’s you! You have to make change. Time is passing. Someone needs to do this.

Aysel adds, Imam and Veronika were interested in creating a documentary community. There had been some attempts in Azerbaijan to do fiction film festivals, but the documentary genre was completely abandoned. So this is something new for our city.

Breaking paradigms

Every aspect of the DokuBaku format aims to nurture collaboration among filmmakers. Aysel says,

Filmmaking isn’t an individual activity. It’s teamwork. You need group harmony, or your film won’t work out. You need a strong pool of people to choose from when you’re building your team. Where else can people like that find each other? That’s what we’re trying to do with this festival.

Knowing that community doesn’t spring up overnight, the team organized a month of pre-screenings leading up to DokuBaku to incubate a critical mass of relational connections. These screenings were deliberately held in intimate settings like Etude, Zenit and Riga Bars (all tucked away in basements with vaulted ceilings) for two reasons: to drive interaction among participants and simply because the coordinating team had friends in those venues. The main festival screenings were also held in the same places to generate a sense of accessibility for everyone wishing to attend.

Aysel explains - DokuBaku is independent and democratic. It’s not elitist. We’ve got this paradox that we’re showing serious international films, and many of them have won awards, but we’re screening them in underground cafes and pubs like Coffee Moffie because we want everyone to feel free to participate. I think this will break something in people’s minds.

Aysel Akhundova moderates a screening. All the discussions were translated into Azerbaijani and English. Photo: courtesy of DokuBaku

Aysel Akhundova moderates a screening. All the discussions were translated into Azerbaijani and English. Photo: courtesy of DokuBaku

The up close and personal pre-festival events also gave the organizers a chance to test drive their interactive screening format for the festival’s line-up of 17 feature-length international documentaries, which cover subjects as diverse as refugees, mental illnesses, family conflicts and global economics. First, each film was introduced by a moderator with some type of personal connection to the film’s subject matter. For example, Oleg and the Rare Arts (Andrés Duque) is about Russian pianist and composer Oleg Karavaychuk, so it was moderated by Zumrud Dadashzade, a Baku-based musicologist. After the audience watched the film, they were invited to discuss it and to ask their questions to the director in person or over Skype.

Foreign directors Hannes Lang (I Want to See the Manager) and Eric Gandini (The Swedish Theory of Love) visited Baku for the festival. Many of the other international directors were not able to attend because of the DokuBaku “zero budget” limitation, but even so, the team is proud that they were able to solicit so many films and obtain licenses to show them all legally. These, too, came together through the team’s relational networks. The 17 films were produced all over the world (from Colombia to Canada to Qatar) and were selected to show a variety of documentary styles, but also for the practical reason that the team had friends in the industry who were willing to let them use these films for free. Aysel says,

I hope people will be able to understand our concept. We had zero budget but good connections, so we’re hoping to make a good festival.

Fuelling the future

“I don’t want to start a revolution. I just want to buy a cow.”

The main idea the DokuBaku team wants to communicate through the festival is simple: whatever it is you’re trying to do, whether it’s produce a film or coordinate a new style of festival, go find some friends and make it happen.

I made my first film with my grandma in my friend’s apartment over two days of shooting, says Aysel. You just have to go and do it and not be afraid of the result.

To nurture that “just go and do it” attitude among emerging filmmakers, the DokuBaku team dreamed up a competition for short documentary films (under 15 minutes) made in Azerbaijan. They accepted 15 submissions which were judged by a jury of five professionals. Two of them are locally based: Maria Ibrahimova, owner of Cinex Azerbaijan Film Production company, and Rafiq Quliyev, experienced filmmaker and Dean of the School of TV and Film Studies in Azerbaijan State University of Art & Culture. Three other judges watched the films from abroad and sent in their evaluations. These included Isona Font, a project manager for Berlinale Film Festival; Diana Tabakov, head of the acquisitions and film program of Doc Alliance Films Platform in the Czech Republic; and Mohammadreza Farzad, Iranian director.

Czech producer and festival organizer Veroniker Janatkova in Zenit Bar during a screening. Photo: Eldar Farzaliyev

Czech producer and festival organizer Veroniker Janatkova in Zenit Bar during a screening. Photo: Eldar Farzaliyev

DokuBaku also held masterclasses intended to provide the impetus for more people to pick up a camera and go make a film. Imam’s goal was to give younger people the chance to learn from the experience of professionals. He recalls a similar milestone in his own life:

When I was young like them, maybe 20 or 25, I didn’t have any chances to go to masterclasses. Then when I was about 27 years old, a producer came from Turkey. She said, “when you make a movie, do something no one has tried before. Then you’ll achieve something.” I still remember that.

But, I ask, what is the DokuBaku team hoping to achieve next in their own careers?

Aysel says, I remember one Czech director, Věra Chytilová, saying that you should make movies about something that bugs you, that really makes you angry. I get angry when people say something untrue about Azerbaijani identity. So I’m working on a movie about that.

Imam dreams of a humble revolution, one mind at a time.

There’s a scene in the movie where Tapdiq says, “I don’t want to start a revolution. I just want to buy a cow.” You know? It’s the same for me. I just want to make a film. For me, revolution must begin in art. If you can make a film, then you can also change people’s minds.

|

Feature-length documentaries on the screening list for DokuBaku: The Dazzling Light of Sunset (2016) - Salome Jashi (Georgia / Germany)Machines (2016) - Rahul Jain (India / Germany / Finland) I Wanna See the Manager (2014) - Hannes Lang (Germany / Italy) Walnut Tree (2015) - Ammar Aziz (Pakistan) God Is Not Working on Sunday (2015) - Leona Goldstein (Rwanda / Germany) Amazona (2016) - Clare Weiskopf (Colombia) Thy Father’s Chair (2015) - Antonio Tibaldi and Alex Lora (United States / Italy) The Swedish Theory of Love (2015) - Eric Gandini (Sweden) Dream Empire (2016) - David Borenstein (Denmark) All That Passes Through A Window That Doesn’t Open (2016) - Martin DiCicco (USA / Qatar) Shooting Holy Land (2015) - Gilad Baram (Germany / Czech Republic) Stranger in Paradise (2016 - Guido Hendrikx (Netherlands) You Have No Idea How much I Love You (2016) - Paweł Łoziński (Poland) Oleg and the Rare Arts (2016) - Andrés Duque (Spain) The End of Time (2012) - Peter Mettler (Switzerland / Canada) Harmony (2016) - Lidia Sheinin (Russia) Normal Autistic Film (2016) - Mira Janek (Czech Republic) |

.jpg)