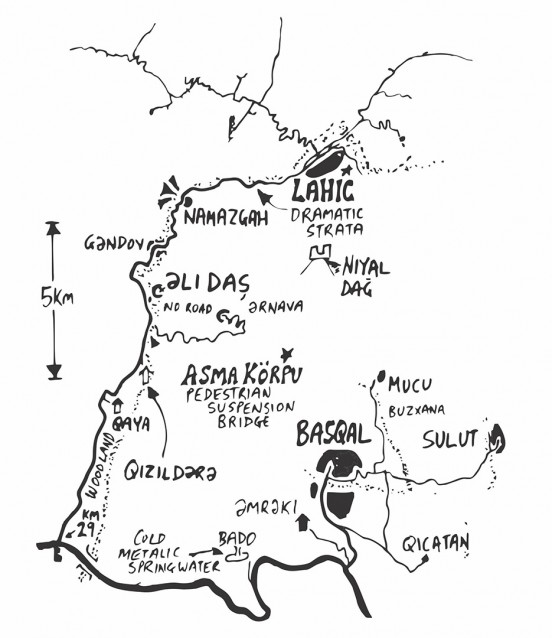

Historic Basqal is famed for its silk (see our 2012 article) while quaint Lahij is known for its copper craft and as one of the most popular destinations for rural tourism in Azerbaijan (we visited for a 2008 article). But what if you want to hike between the two? A great idea, it turns out, and arguably one of the best day trips you can do from Baku if you’re looking for variety and lots of great views. Mark Elliott describes the experience.

In its utter simplicity, the Araz Chaykhana in Basqal is one of my favourite rural teahouses. In its grassy garden you’ll find the old men of the village sporting caps and jackets just sitting and chewing the social cud in balmy air that stays graciously cool beneath the rustling leaves of some lovely chinar trees. Our small group, a British journalist, Azerbaijani banker, American tourist and Emil, a trusty guide from Camping Azerbaijan, settle down with a pot of kəklikotu çayı, tea gently flavoured with wild thyme gathered from mountain pastures. Foreigners are still relatively rare here and we’re rapidly a centre of attention. Oh yes, Basqal is historic, I’m assured by a tag team of local white-beards, ever keen to repeat the story of Basqal silk winning a silver prize in a 19th-century trade contest in London... though exactly which year that was, nobody can quite agree upon.

The keleghayi dyeing workshop in Basqal is now a popular workshop with tourists. Photo: Irada Gadirova

The keleghayi dyeing workshop in Basqal is now a popular workshop with tourists. Photo: Irada Gadirova

The village’s link to silk production continues in the form of a delightfully low-tech dyeing workshop with old bathtubs full of natural dyes. It’s almost next door to the teahouse – inside are more old gents, some of whom have worked here for five decades. Apparently work depends on somewhat irregular demand, but today they are busy stamping out waxy shapes using laboriously cut buta-form handstamps and creating patterns for classic keleghayi scarves – one of UNESCO’s curious choices as an aspect of intangible world heritage. The workshop also has a small museum room showing a few of the raw materials involved. But a 4WD Niva has arrived to whisk us 5 km up to the start of our trek above the small hillside of Taghlabiyan. Fitting with Camping Azerbaijan’s policy of trying to ensure that at least a trickle of income reaches the villages that their hikes pass through, driver Sakit is himself from Taghlabiyan. Any chance that we’ll find some fresh tandir bread? we ask Sakit once the crew has crammed itself into his Niva. We hadn’t planned to inconvenience him but such is the local sense of hospitality that we spend the next few minutes stopping at a series of windows asking for the latest baker’s wares. Apparently we’ve drawn a blank and we arrive at the forest edge well above Taghlabiyan. But before he lets us start our walk, Sakit cries out a few barked phrases into the orchard below. Children’s voices reply. And within a couple of minutes a boy scurries up the hill carrying the most delicious fresh bread, complete with a little bag of fresh curd cheese. Bon voyage!

One of the great advantages to this hike is the variety of landscapes one passes through. Pictured here is a beautiful forest shortly after leaving Basqal. Photo: Mark Elliott

One of the great advantages to this hike is the variety of landscapes one passes through. Pictured here is a beautiful forest shortly after leaving Basqal. Photo: Mark Elliott

The first stretch is a wide, clear track that eventually leads to Zarnava, best known for the famously perilous suspension footbridge that connects it to the Lahij road. The track rollercoasters through very pretty mixed woodlands, the ground crunchy with beech leaves and occasional fruit to be scoffed – blood-drop red zoghal (cornelian cherries), small yellow alcha (sour plums) and some of the tastiest blackberries imaginable. After 15 minutes a refreshing source of ice-cold spring water makes me rue having just purchased two litres of commercially bottled BonAqua. In several places the trees clear to afford very striking views towards a striking wall of erosion-cliffs on the near horizon. These are topped with trees to the east and grasslands to the northwest. After half an hour, turning off the main track, there’s a particularly memorable viewpoint knoll that’s ideal for photography. The trail then crosses what looks like a natural causeway between two woodland ridges. In mid-distance to the left you can see the houses of Zarnava layered up the hillside. In a valley away to the right is Muju. Across the “causeway” things get more challenging. Luckily it’s a dry day – the trail starts up a mud-floe that would have been virtually impossible in the rain. Then it climbs very steeply up the eroded cliffside zigzagging up 200 vertical metres on a path that has slippery sections. Keep going, I tell myself – forward motion prevents slipping, though goodness knows how I’d get back down if we had to. There are few rocks, roots or other handholds to cling to though every couple of minutes we find little footholds where we can catch our breath. The top looks deceptively close but it takes nearly half an hour of panting and sweating to drag ourselves up onto the grassy upper slopes above. Here a single umbrella-shaped hawthorn seems to have been placed deliberately as an ideal picnic spot and with gusto we tuck into Sakit’s delicious bread and cheese for sustenance. The contrastingly tasteless sandwiches I’ve carried from Baku are quietly forgotten.

Visions editor Tom Marsden scrambles his way up the steep and slippery first ascent north of Basqal. Photo: Mark Elliott

Visions editor Tom Marsden scrambles his way up the steep and slippery first ascent north of Basqal. Photo: Mark Elliott

Suitably refreshed we start what feels like an altogether new walk. We’re on open grasslands that climb to a cut between two modest peaks. One of these is Niyal Dagh, the summit of a mountain reputedly once ringed by a vast series of castle walls that was described in the 10th century by historian Masudi as being one of the world’s most impenetrable fortresses. There’s no sign of a single stone now, but the views are superb with a hazy wall of mountains to the north including the holy peak of Mt Babadagh forming a dreamlike apparition on the horizon. And just below the high point, guide Emil – who has plenty of experience being from a local village himself – cautions us to move slowly. There will be dogs ahead. This is a yaylaq (summer sheep pasture) and the shepherd dogs are taught to be fierce enough to scare the daylights out of local wolves. Or should that be nightlights? According to the trio of shepherds that we meet a little further down, bears approach the camp every night. Do they ever take sheep? Of course, once in a while they win. But not that often. Now September is coming to an end and the “game” will soon be over for the year. The flocks are about to start their annual migration down to winter pastures – a four- or five-day epic hike for animals and shepherds alike to the Hajiqabul area. The preparations are almost complete and the shepherds’ horses are already packed. But they find time to show us the way to a trickling spring which is ideal for replenishing our water bottles.

In comparison our walk is just a stroll, and from here on it will be downhill almost all of the way, passing a second shepherds’ camp then dipping into the woodlands again and descending on rain-eroded gulley trails. After around 20 minutes we find two ruined walls built of what seem to be ancient grey stones. Were it anywhere near habitation we might assume it was a long abandoned barn ruin. But apparently, it is actually a minimalist wall fragment of the Niyal Dagh (aka Girdman) fortress wall. A vaguely discernible line of stones climbing between trees behind suggest that this might indeed be a possibility. But if so, what is most striking is just how completely even the greatest human constructions can be wiped away by nature. However unimpressive, the castle does prove to be useful as a signpost of sorts, the trail making a sharp 150-degree turn beside it. A little further down, a pyramidal rock provides an easily accessible viewpoint to scan the valley below, then it’s a jolly downhill skip to a small river ford that deposits us at Jennet Baghi, a lovely rustic orchard-garden restaurant at the edge of Lahij. We’ve made good time and as a reward we get an hour or two to potter up Lahij’s picturesque cobbled main street. We peep into a few of the famous copper workshops. Many have been gentrified into glittering boutiques but Kebelemi’s place is unchanged. We’ve been smiths here for six generations, he says proudly as he hammers on a bar of red-hot iron pulled from the forge. Amid the dusty pots and aftafas, a portrait of Lenin in a comfy chair looks on. And on the wall above is a shrivelled form that looks like some sort of baby dinosaur fossil. That’s the cat, he laughs. It’s 150 years old. The master of those days must have loved him!

A trio of Russian tourists are trying on colourful costumes for photo opportunities and a Bakuvian family is giggling merrily at dad as he tries on a sheepskin hat that transforms his head into what looks like a giant dandelion clock. Indeed, being Sunday, the loveable village is abuzz with day-trippers, but somehow the place seems that much more vivid for having got here on foot, senses sharpened by the hike and the realisation of just how beautiful are its surroundings.

About the author: Mark Elliott is a travel writer who has been covering Azerbaijan since 1995. The fifth edition of his guidebook is currently being edited for 2018 publication.