The picturesque village of Ivanovka in the Ismayilli region is known as much for its unusual inhabitants as it is for its natural farm products. It was founded sometime in the 1830s by Russian Molokans (a strand of spiritual Christians) forcibly resettled to the Russian Empire’s southern borders for not conforming to certain tenets of the Orthodox church. But contrary to the expectations of their oppressors, the Molokans soon built an industrious community and began to prosper in Azerbaijan.

Their hard-working, communal nature meant the village especially flourished in the Soviet era, during which its collective farm gained an enviable reputation for its wealth and productivity. Since independence the collective farm has unsurprisingly gone into decline but unlike almost every other in the former USSR, it remarkably still functions. Today the kolkhoz operates in conjunction with private enterprise as many Ivanovka families, who today include many Azerbaijanis and Lezgins, produce dairy products such as tvorog, smetana and cheese, whose organic qualities maintain the Ivanovka brand’s longstanding reputation around the country. Another draw for Azerbaijani gastronomes is the local honey.

many of Ivanovka’s honey makers were true masters, with beekeeping skills passed down and honed through several generations

This aspect of village life grabbed my attention during a recent visit when I tasted honey so perfectly sweet and smooth that a mere teaspoon and armudu of aromatic tea were more than enough to relax me into the rhythms of life beneath the Caucasus Mountains. Moreover, subsequent inquiries revealed that many of Ivanovka’s honey makers were true masters, with beekeeping skills passed down and honed through several generations. I wanted to understand something of this culture – how did it all begin and what was the secret to Ivanovka honey?

Watch your step

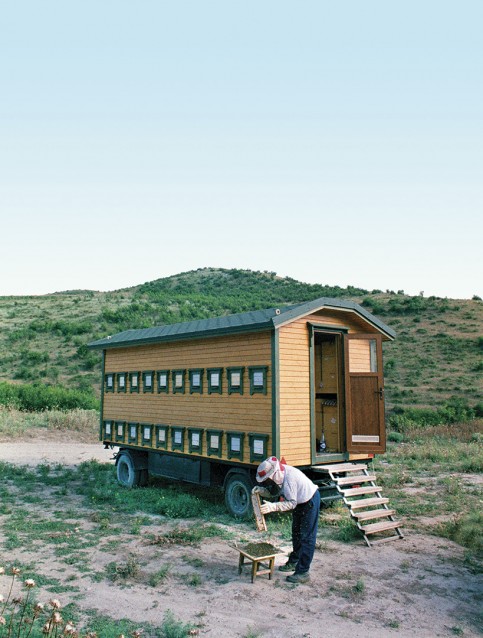

My journey began with Vasya Minnikov, the man responsible for that maiden jar of honey. Vasya had agreed to show me his wagon and modus operandi, which meant travelling one Sunday in mid-June about 20 km or so from Ivanovka along the road to Goychay. As we cruised along the scenic descent in Vasya’s clapped-out Lada estate, weighed down with beekeeping equipment, he began to explain the basics:

The key to making tasty honey is using a variety of honey plants, which is why one particular sort of honey – mayskiy myod (May honey), made from nectar gathered from over 15 plant types – is thought to be the best. Related to this is the overriding key principle that everything depends on the weather. Over the season Vasya gradually moves his hives from the lowlands, where temperatures are warmer and flowers begin to bloom at the end of winter, back up towards Ivanovka (located on the top of a hill) and eventually into the mountains. Honey is only made during about a three-month period over spring and summer, so Vasya has to produce enough to keep both him and the bees going for the rest of the year:

We steal their honey but we leave enough for them to survive through the year. So we make sure that they have enough and we have enough.

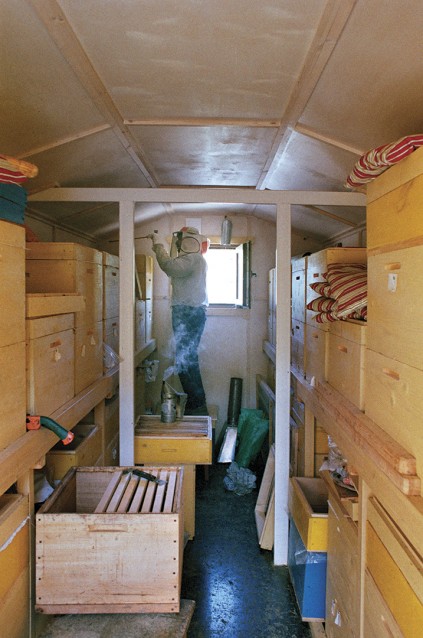

In winter, the bees are kept in the wagon in a village lower down and watched over by a local villager for a small fee and complementary honey supply. But for Vasya this doesn’t mean that everything stops; the off-season is spent preparing for next season’s production period – fixing and cleaning hives, arranging equipment and planning ahead.

Having descended from Ivanovka, the landscape quickly turned from lush green to rocky and arid. At the bottom of the valley Vasya gave a tug at the Lada wheel and off we went bumping along a dirt track leading deep into the bush. A few minutes later his lonely wagon appeared on the horizon, standing defiantly amid the rugged wilderness.

Have you ever been stung before? Vasya asked, as we pulled up, the question startling me into recalling that beekeeping is a serious business. At their worst allergic reactions can be fatal. In truth I wasn’t totally sure and answered with some trepidation that I thought I’d be all right; after all, one summer in Pennsylvania I stepped barefoot on a hornet’s nest, which left me in pain but very much intact.

As for Vasya, he always dons his bee-protection net but all the same admitted that he is stung multiple times on a daily basis, which is always a painful experience. Another beekeeper I would meet several weeks later recalled receiving up to 20 or 30 stings in quick succession during spates of particularly aggressive bee behaviour. His remedy, however, was refreshingly simple: We just drink 50g of vodka. A small dose of spirits neutralises the pain.

With the unforgiving heat beating down on the harsh scrubby terrain, Vasya set about tending to the hives and I marched off up the Martian hillside in an attempt to find a clever camera angle. About 50 or 60 metres later I stopped. Utter silence. I drew my eye to the camera’s viewfinder, but before I could pull the trigger my zen-like concentration was interrupted by Vasya’s rough voice:

Tom... Tom, look where you step, he shouted in a perturbingly serious manner, (moment’s pause)... there are lots of snakes here.

I froze and looked scrupulously about. Nothing, but in any case it would be a good idea to retreat, I reasoned, and trod carefully back to the wagon as a precaution. When I arrived Vasya explained rather casually that he’d seen plenty of snakes around and kept a rifle in his car to shoot them. He’d even trodden on one once and been bitten, but fortunately his thick boots had kept the venom at bay.

After a while Vasya exited the wagon, stripped his protection netting back and meandered over to a ridge overlooking a scorched creek lined here and there by wild pomegranate trees. There he took a breather from collecting the honey, puffing away on a cigarette and dripping with sweat – it was still ferociously hot at 6pm but Vasya was visibly in his element in the countryside: I come out here and relax, he said.

I liked it too I must admit. Honey, nature, wild pomegranates and tales of hunting venemous snakes proved enticing compared to life behind the editing desk. So several weeks later I returned, determined to continue my exploration of the Ivanovka honey trade, to meet several other beekeepers and spend a little more time in this last bastion of Molokan culture in the South Caucasus.

A very risky business

The quality of any honey depends on the area in which it is produced, explained another Vasya – Vasya Kazakov – who together with son Andrey runs a family honey business. Ivanovka sits in a special zone, in the foothills of the Caucasus Mountains where both the lowland steppes and mountains are within easy reach. The special aroma of the honey is thus a result of the rich blend of grasses, bushes, plants and climactic conditions found in this region, and the abundance of sun gives Azerbaijani products an extra kick: Even the apples have a smell, said Vasya, as we chatted one evening in his yard.

Yet despite the natural richness of the honey, Andrey explained that the conditions here for beekeeping are harsh and the yield very small, which drives prices up – this season a kilogram is selling for 30 AZN in Baku. Russian honey, by contrast, is under half the price because there the plants give nectar at much lower temperatures, making honey easier to produce. Yet when it comes to taste, there’s no comparison:

There’s eau de cologne – it’s a strong smell – and there’s Chanel No.5, which is very tender. Well ours is like this, Chanel No.5, and theirs is like eau de cologne, from Lime trees – very sharp. You can have it once or twice in the morning and then you won’t be able to eat it any more... but this one [Ivanovka honey – Ed.] you can eat every day, it’s soft, explained Vasya.

Producing this Chanel No.5, however, is a risky business. Four years ago, of the Kazakov’s 200 families of bees, only 50 remained by the end of the season, the worst year Vasya had seen in almost 40 years of beekeeping. Later they learned the reason – the pollen wasn’t sound enough for the bees to be able to feed their young – but it was too late to save any of them.

Perhaps this explained why almost all the masters with whom I spoke referred to beekeeping as a science. One man, an elder in the Molokan community, went slightly further: It’s an infectious disease, he said.

Everyone here is following the latest technologies on the internet and in the news, said Vasya, who also keeps old issues of Pchelovod (The Beekeeper), the popular Soviet-era magazine. The reason for this is simple: under socialism there was no competition, so tips and best practice were accessible and shared. But nowadays things are a little different:

Everyone knows the general rules, but every professional beekeeper has his slight variations, special skills or ways of doing things, Vasya admitted.

Many Ivanovka villagers keep bees at home. Here Timofey Ryadayev checks on the beehives in his front yard. June, 2017

Many Ivanovka villagers keep bees at home. Here Timofey Ryadayev checks on the beehives in his front yard. June, 2017

Dance of the bees

One of the first families to produce honey in Ivanovka was the Ryadayevs. Head of the family Timofey remembered the early days well: It all started from absolutely nothing, he said. Before and just after the war some Ivanovka residents kept bees in hollowed-out wooden tubs, without the use of any specialised equipment. Everything was being done by hand. Then in 1957 his father bought two hives and put them in the yard and the following year they acquired two more. The next stage of development was moving the hives from the yard into the fields, a process pioneered by Timofey and his father:

We spent all night transporting them, Timofey recalled. We even brought the honey extractor and pumped out the honey right there. We pumped out two flasks in the field. One flask is 50kg, so we pumped out 100kg in a day there in the field. Then we brought them home in the car.

Others then followed in the Ryadayevs’ footsteps and eventually wagons were introduced, which greatly simplified the transporting and housing of the bees and ultimately meant more honey for less labour. Today, for Timofey, honey remains both a pastime and a family business. You can’t not love it, he said. His enthusiasm has even rubbed off onto his granddaughter Lena, who together with mother Olga introduced me to the secret world of bees:

There’s this thing that I really like in beekeeping, said Olga. When the bees fly towards the nectar... so they fly around and find out that an acacia has blossomed over there for example. They then fly back and do this thing called the dance of the bees: with their movement they show where the rest of the bees need to fly.

It’s a miracle of nature, agreed Lena, who revealed another interesting habit: Their hives are always clean. If a bee dies inside a hive – I saw this the first time and was amazed – another bee carries it out with its legs and teeth.

A good year for honey

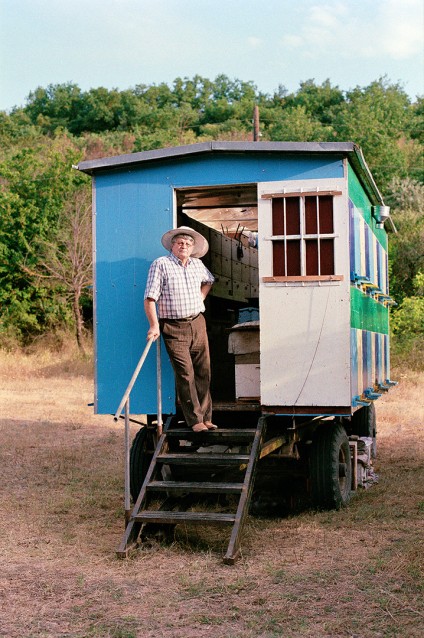

Not far from the Ryadayevs live the Zhidkovs, another pioneering family of the Ivanovka honey trade. Grisha Zhidkov is in fact a cousin of Timofey and their fathers began keeping bees at around the same time. During a recent excursion to Grisha’s wagon in the collective farm fields, he too recounted how it all began.

Grisha’s father was injured in a battle near Kharkov, Ukraine, during the war and returned to Ivanovka to work as a carpenter at the collective farm. One day in 1956 he came home for a lunch break and suffered a heart attack. He recovered but couldn’t return to the physical exertions of carpentry, so he began to keep bees instead. Grisha helped out during the school holidays and developed into a fully-fledged beekeeper by his early twenties, continuing to practise, albeit only part-time, throughout his career as a PE teacher at the local school. When he retired his passion for beekeeping and its financial rewards encouraged him to go full-time and the family business now allows them to live quite well: the Zhidkovs have 40 hives which can bring in about 20,000 AZN per season through sales to a clientele built up over 40 years. But, as I’d become used to hearing, Grisha warned that you have to work exceptionally hard for it.

There’s noise that annoys you at night, but then there’s the sound of the sea or the buzzing of the bees, it really calms the nervous system

Prior to departing for the fields, Grisha’s wife Tatiana, who deals with sales, had explained that this season has been great for honey: the colour is amazing this year, she’d said to a client that had just dropped by. Meanwhile I was busy tasting. The Zhidkovs’ honey was wonderfully light and soft in texture and almost butterscotch or caramel in taste. You see how the honey jumps back up, Tatiana said, focussing my attention on the honey’s thickness as I dipped my spoon into the golden saucer and began twisting sharply until the treacly trail came to an abrupt end. That’s a sign of the honey’s maturity, she assured me.

Later, in the fields, Grisha pointed out the main plants used to gather nectar by the bees at this late stage in the season. These were mostly thorns (or alhagis), of which there are several different types: blue, yellow, pink, as well as a variety called “camel.” One thorny bush which local beekeepers call by its Azerbaijani name qaratikan (its formal name in Russian is chernaya kolyuchka (black thorn); literary name – derzhi-derevo (hold-tree); and Our ancestors call it the “voltsovnik,” Grisha said) is especially popular. The key feature of these thorn bushes is their ability to produce nectar at temperatures of over 30 degrees, ideal for honey making in hot Azerbaijani summers.

Deep in the fields the colours of Grisha’s wagon and the characteristic buzzing of bees were the only sign of life for miles around and it was only out here, once again, that I began to realise why, beyond the financial gains, beekeeping was such an “infectious” pastime. I recalled something Vasya Kazakov had told me the previous evening:

We have our wagon, right, and when we don’t have anyone guarding it, we stay there ourselves on a foldaway bed. When you’re in the wagon at night and you hear that sound – bzzzzzz.... – it’s a medicinal sound. There’s noise that annoys you at night, but then there’s the sound of the sea or the buzzing of the bees, it really calms the nervous system.

As the evening drew in Grisha and I drove slowly back through the rolling hills. Fields of giant sunflowers stood resolutely against the peach-hued sky. It was a dramatic, poetic scene and a fitting end to my exploration of what I had begun to consider – with its medicinal and culinary qualities, financial rewards and small yield – Ivanovka’s liquid gold.