In early November 2018 a group of local press representatives were led on a specially organised tour of cultural monuments currently being restored in Icherisheher which included a recently discovered hammam. Sadly Visions missed this opportunity, although fortunately that didn’t really matter as several weeks earlier Tom Marsden had been given an impromptu private tour of this new cultural monument by Mr Kamil Ibragimov, head of the archaelogical department of the Icherisheher administration, while researching Azerbaijan’s celebrated hammam culture.

The recently excavated hammam is located underground near the iconic Qosha Qala entrance to Icherisheher (Baku’s Old City) and is thought to have been built sometime in the 17th century as part of the nearby Baku Khan’s Palace complex. More precise details haven’t been grasped, as no markings or inscriptions have been found on the hammam’s walls to indicate either the date of construction or the name of the owner, as is often the case with Middle Age hammams.

There is more certainty, however, about how this hammam disappeared: after the Russians conquered Baku in 1806, it was filled with earth and a military garrison was established on top that remained until the end of the Soviet period. As a result, nothing could be done to uncover the hidden baths after they were first discovered in the late 1960s by none other than Kamil muellim’s father, who as head of an archaelogical expedition had climbed through one of the small windows in the Old City walls that led straight into one of the hammam’s buried chambers. Fortunately, though, his father drew a map indicating the location of this and other archaelogogical finds in Icherisheher, making it easy to pinpoint when the conditions finally appeared for excavations to begin in 2015.

While stuffing the hammam with earth may seem ruthless, the Russians’ approach had one major advantage: it protected the hammam from structural damage, preserving it in remarkably good condition and ultimately rendering it today the incredible cultural and architectural monument of the khanate period that it is. Three years on, efforts to preserve it are in full swing and are being carried out by Atelier Erich Pummer GmbH, the Austrian company responsible for breathing new life into the old fortress walls, the Maiden Tower and the Shirvanshahs’ Palace (see Restoring Medieval Baku for more about that).

The khanate-era hammam should open as a museum at the end this year. Photo: courtesy of Kamil Ibrahimov

The khanate-era hammam should open as a museum at the end this year. Photo: courtesy of Kamil Ibrahimov

On the day I visited, an Austrian specialist was busy restoring the original wall plastering in a small private bathing room. He is studying the solutions and preparing recipes identical to the historical ones, and then he will restore these parts, explained Chingiz Neymanzade, manager of the Azerbaijani representation of the Atelier Erich Pummer, highlighting the painstaking nature of the work but also its importance given plans to turn the monument into a museum to Baku’s hammams. When tourists and specialists visit, they will be able to imagine how the baths originally looked, he explained.

The museum is expected to open at the end of 2019, but in the meantime news of the discovery inspired us to revisit the legendary hammam culture that used to flourish throughout the city.

A social institution

For a more detailed look at this unique phenomenon, I would encourage you to read The Hamam Culture of Old Baku, which appeared in Visions in 2013. Suffice to say that in Icherisheher, which was the extent of Baku until the mid-19th century, hammams used to be found in every mehelle or small districts consisting of from only a few houses to a several neighbouring streets. Not far from the hammam would be a mosque and the two were extricably linked: while the mosque catered for spiritual purity, the hammam focused on physical cleanliness in an age before homes were kitted out with private baths and showers and before Baku had a reliable water supply.

Hammams were therefore an essential means of maintaining public hygiene. It is even said that, in the days when travellers passed through Baku along the Silk Road, they were first requested to bathe in hammams located by each of Icherisheher’s two entrances and, according to Kamil muellim, were also made to burn their clothes and put on new ones to minimise the risk of diseases circulating in the city.

Hammams were always strictly segregated and given the hours both men and women spent at their local haunts, they played a distinct social role. Summarising this, Kamil muellim said: People got together, chatted, discussed. It was a social institution where you would relax and, everything that had built up inside of you, you would talk about it and share it.

According to some local media reports, Baku residents would even visit the same hammam throughout their lives. An exception to this might have been when women paid a visit to a different one to look for brides for male relatives. After all, women’s hammams were the only place young Muslim girls could be seen beneath the veil and therefore were a natural hunting ground. Later on in the marriage process, brides and grooms and their accompanying entourages would spruce up in the hammam before the wedding celebration; even today some men continue the tradition of unwinding there on the eve of a wedding as a sort of stag party.

But that’s about the extent to which Baku’s old hammam traditions survive today. Visits began to decline in the Soviet-era as apartments were increasingly fitted with their own washing facilities and traditional old hammams were modernised. As a result, many historic hammams were long ago converted into shops, markets, teahouses and homes, or simply no longer exist. Yet there are still a handful of establishments frequented by a small minority of local enthusiasts keeping the hammam culture alive.

For the most authentic venue to experience the steamy rituals of the past, however, there can be only one winner: Agha Mikayil Hamami – Baku’s oldest functioning hammam. Needless to say, I recently paid a visit.

Agha Mikayil hamami

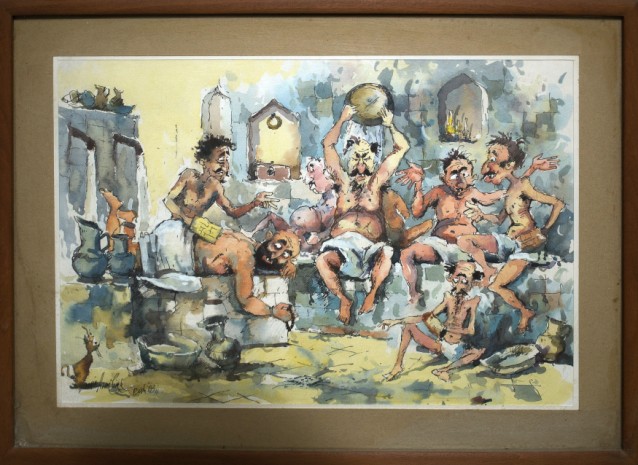

The Eastern ambiance and timeless décor of this 18th-century hammam built by a wealthy merchant from Shamakhi has made it popular as both a tourist attraction and a film setting – locals will be quick to point out that Agha Mikayil was used for a famous hammam scene in the classic Azerbaijani film, If Not That One, Then This One (in Azerbaijani – O olmasın, bu olsun).

The ritual begins in the changing area where you’re given a red piece of cloth called a fite that wraps around the waist and for centuries has been the standard hammam attire. From here a dimly lit corridor leads to the baths, a square-shaped room of oriental design full of taps, water, steam and marble.

The key piece of equipment here is the parkhana (steamroom) and prior to entering you’re encouraged to put on a felt hat reminiscent of a Bolshevik budenovka to stop your head from overheating. On my visit, the steamroom is so hot that I struggle to breathe and after just a few minutes find myself fighting the almost irrepressible urge to dash towards the nearest source of cold water.

To make matters worse, Orkhan Gasimov, the hammam’s manager who accompanies me throughout my visit, reaches over and picks up some eucalyptus twigs or venniki, as they’re affectionately called in Russian (unsurprisingly, after so many years under Russian influence, some banya practices have found their way into the Azerbaijani hammam). Orkhan instructs me to lie face first on the upper deck of the parkhana and uses the bushy twigs to gently whip my thighs, calves, back and buttocks. The room fills with a powerful aroma that brings some degree of respiratory relief but transforms the parkhana into a full-blown furnace, leaving me worringly light-headed and listless.

After about 30 seconds, Orkhan gets wind of my struggles and ushers me out the door towards the tiny plunge pool in the far left corner. I shuffle over as rapidly as possible trying not to slip on the liquidy marble tiles or short metal stairs and, having launched myself in, the relief is almost indescribable. I want to stay here forever, yet sadly all too soon I’m jumping again between a series of hot and cold showers. Orkhan then signals a tea break – another key aspect to the Azerbaijani hammam. A visit should never be rushed; the hammam is a place of relaxation and it’s not uncommon for guests to move back and forth between tea and treatments for up to eight hours.

Over tea in the foyer, I learn Orkhan’s story. He is originally from Aghdam and came to Baku after the town was occupied in July 1993 during the Karabakh War. He found work at the hammam, which was run by his uncle, and has remained for over 20 years. So much of his life has been connected with the hammam that he describes himself as “amphibious” and says that the local baths are the first thing he looks for when arriving in an unfamiliar place.

|

Agha Mikayil Hamami (16, Kickik Qala, Icherisheher; +994-50-345-21-44) – Women’s days are Mondays and Fridays; all others are for men. Basic entrance is 10 AZN while a visit with all the treatments will cost you about 60 AZN.

|

Soap and honey

Returning to the baths about an hour later, it’s time to experience some of the traditional treatments. These include kise, an all-over deep-pore body scrub; mochalka, a soapy wash performed straight after kise to get rid of all the grime left from the scrub; and massages with coffee, salt and honey.

The first two are performed while lying on a marble bench. During kise, a kisechi (scrubber) dons an abrasive glove and rubs out all the grit hiding beneath your skin. Though forceful and somewhat exposing, it leaves a pleasant light tingle rushing across every limb. The kisechi here is Alesker Azizov, a taciturn former cook who’s also been working at the hammam for close to two decades, saying he enjoys it because “it’s clean work.”

Removing alarming quantites of grit, he shows it to me demonstratively, as though to shame me into coming more regularly. I recall something Kamil muellim said:

You know, if you went every week it would be very good, or at least twice a month, you would feel it after half a year, how cheerful you are. That’s really how it is.

To remove any dirt left over after kise Alesker switches to a treatment called mochalka, which means swapping the abrasive glove for a soft hand towel and covering me from head to toe in a foamy soap so silky and smooth that I feel in danger of slipping right off the table.

|

Other hammams worth visiting: Agha Zeynal hammam (5 Saftar Quliyev Street, Icherisheher; +994-55-639-19-99; men only) – also in Icherisheher and named after the oil-boom millionaire that built it as a private hammam for his guests. She-Bi Hammam (41 Murtuza Mukhtarov Street; +994- 50-540-08-41; men only) – built in the early 19th century in the old district known in recent times as Sovetski. It’s popular among civil servants working in ministries nearby. Akhund Hammam (141 Murtuza Mukhtarov Street; +994-12-595-50-59; men only) – late 19th-century hammam named after the akhund (cleric) serving in the mosque a few doors down. Tezebay Hammam (30 Sheikh Shamil Street; +994-12- 492-64-40; men’s and women’s hammams located next door) – housed in an oil-boom mansion but Tezebay has only been a hammam for about 20 years. It’s eccentric and modern but more expensive with the full set of treatments costing a little under 90 AZN. |

After another short break the finale begins – massages with coffee, salt and honey. The benefits of rubbing salt into one’s skin are quite well documented. According to Massage magazine, these can include balancing the body’s pH, aiding metabolism, circulation, calming the nervous system and rejuvenating the skin. Less well known is that honey helps heal small cuts and scrapes and coffee reduces inflammations, polishes the skin and soothes with its rich aroma. I find it all unusual, exotic and relaxing and a fitting end to my hammam experience.

In truth, this was my first visit to an Azerbaijani hammam in over four years of living in the country, the main reason being that they aren’t well advertised; the tourism potential has thus far been overlooked. Yet given their former social significance, therapeutic treatments and intriguing interiors, going to an old hammam is a fun way to recharge your batteries while simultaneously immersing yourself in Baku’s sociocultural past. And who knows, perhaps the recent discovery of a uniquely preserved bathhouse dating back to the 17th century will make this quirky cultural phenomenon fashionable again.